Development of the Yankees Scouting Staff

This article was written by Daniel R. Levitt

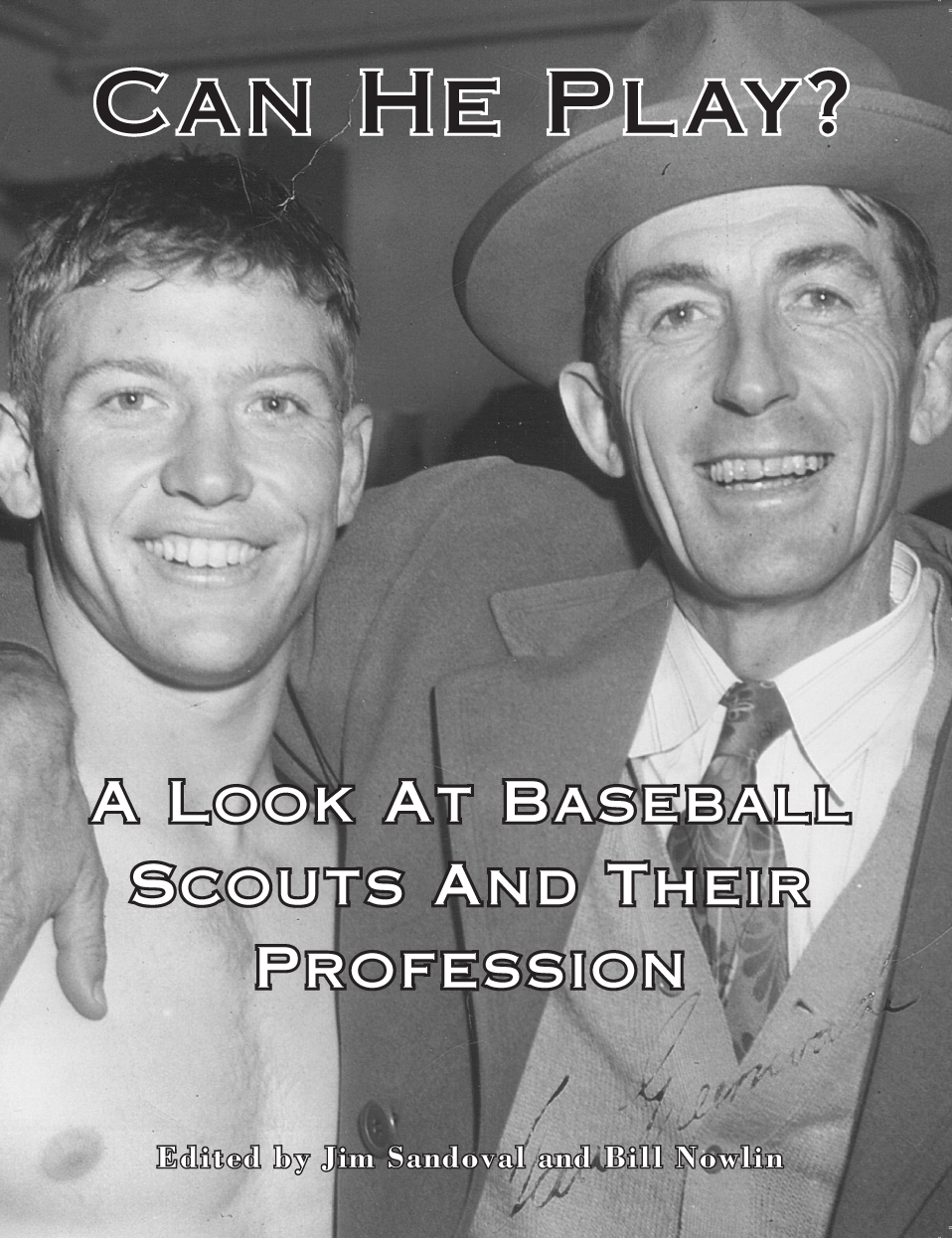

This article was published in Can He Play? A Look at Baseball Scouts and Their Profession (2011)

Beginning in 1921 the New York Yankees embarked upon one of the great stretches in American sports. Through 1964 the Yankees captured 29 pennants and 20 World Series championships. There are many ingredients that go into a winning team, but most obviously a team needs good players.

Beginning in 1921 the New York Yankees embarked upon one of the great stretches in American sports. Through 1964 the Yankees captured 29 pennants and 20 World Series championships. There are many ingredients that go into a winning team, but most obviously a team needs good players.

Today a major-league front office has many avenues for acquiring players—free agency, the amateur draft, trades, the Rule 5 draft, Latin American free agents, etc.—the usefulness of each depends on the ability of a team’s scouts to recognize talent. During the heyday of the Yankees dynasty, which occurred before the introduction of the amateur draft, a scout not only had to identify who would become a major-league ballplayer, but be able to obtain them in a competitive environment. In the 1920s and 1930s New York assembled a legendary team of scouts who, in conjunction with baseball’s most professional front office administration, delivered a consistent stream of baseball’s top talent.

Prior to the end of World War I, franchises generally operated without a general manager. Player personnel decisions were typically overseen by the owner and manager. The distribution of authority between the two depended primarily on the level of control the team president or majority owner wished to retain for himself. Many owners, like Barney Dreyfuss in Pittsburgh and Charles Comiskey in Chicago, prided themselves on their baseball smarts and maintained control over player personnel moves and decisions. At the other end of the spectrum the New York Giants employed a willful genius in manager John McGraw. Outside of a veto on significant cash outlays, ownership allowed McGraw essentially free rein on all personnel matters.

Baseball ownership evolved after World War I as more sophisticated American industrialists bought into the sport. These new owners recognized the importance of more professional administration to move beyond the limitations of operating like a small business. After the 1920 season the Yankees owners, brewery magnate Jacob Ruppert and his partner Tillinghast L’Hommedieu Huston, concluded that they needed to revamp their business. The two brought in Boston Red Sox manager Ed Barrow as a de facto general manager to professionalize the front office.

Barrow inherited a small scouting staff led by manager Miller Huggins’s best friend in baseball, Bob Connery, and ex-major-league outfielder Joe Kelley. Connery in particular was generally regarded as an astute judge of talent, having signed future Hall of Famer Rogers Hornsby while working with Huggins for the St. Louis Cardinals. Barrow clearly appreciated the importance of a strong scouting staff and during his long tenure in the Yankees front office often credited the Yankees’ success to having the best scouts in the business. Immediately upon assuming his new position in New York, Barrow hired his Boston coach and scout, Paul Krichell, to bolster the scouting staff. Destined to become one of the most successful of all ivory hunters, Krichell was responsible for many of the Yankees’ stars.

In the early 1920s, scouting evolved as the economic landscape shifted in favor of the high minor leagues. The major-league/minor- league draft in which teams could draft players from lower leagues was significantly diluted, effectively protecting the high minor leagues from losing players involuntarily to the majors (much to the detriment of the players). Scouts not only needed to identify the best players but negotiate with minor-league owners to pry them away for the lowest acceptable price. (Even before the attenuation of the draft, players were sold to the majors, but the threat of the draft acted to keep the prices down.)

The 40-man roster was another key factor at work in the 1920s. Like today, a team had a 40-man roster of players under its control and a 25-man active roster during the majority of the season. Unlike today, however, when a team can control many more players through its farm system, in the ’20s all players under control of the major-league team counted against the 40-man roster; thus, franchises could effectively control only 15 minor leaguers. Of course some teams, particularly Branch Rickey’s St. Louis Cardinals, maneuvered within and around these rules, but in any case the rules encouraged scouts to devote the preponderance of their effort to scouting the high minors for near-ready major-league players.

Within this environment the Yankees proved extremely successful in the early to mid-1920s. Krichell and Connery signed Columbia University baseball star Lou Gehrig to one of their precious roster spots and optioned him to the minor leagues. A couple of years later Connery pushed for the Yankees to purchase another future Hall of Famer, outfielder Earle Combs, for $50,000— at the time the highest price ever paid for an American Association player.

By early 1925 Barrow was down to only three scouts, Ed Holly (another former Red Sox scout), Bob Gilks, and Krichell. Kelley had retired in 1924 and Connery, in conjunction with Huggins, had purchased a controlling interest in the St. Paul American Association franchise. To rebuild his scouting staff, Barrow brought in two new scouts and organized his staff geographically. Former Vernon (Pacific Coast League) manager Bill Essick was assigned the West, and Eddie Herr, another old friend of Huggins, was responsible for the Midwest. Of the holdovers, Gilks maintained his Southern focus, Holly took over New England and the East, and Krichell continued scouting the colleges and New York.

The Yankees used a team approach for the most expensive players. When Barrow wanted to evaluate Salt Lake City star Tony Lazzeri, he sent Krichell to evaluate him. (Krichell liked to joke that Barrow, who often dispatched his scouts to review prospects on short notice, began every telegram with “immediately” or “at once.”) Krichell liked what he saw and recommended Lazzeri despite his huge price tag of $50,000 and five players. Barrow dispatched Holly to confirm Krichell’s judgment and practically ordered Connery, now in St. Paul and no longer a Yankees employee, to also validate Lazzeri’s ability.

In St. Paul, Connery maintained his close ties with Huggins and the Yankees front office. Because of this relationship, St. Paul sold quite a few of its stars to the Yankees and accepted a number of prospects back on option. In retrospect this relationship benefited the Saints much more than the Yankees. New York spent roughly $300,000 in less than a decade purchasing St. Paul’s best players. Other than Mark Koenig, none developed into a quality major leaguer. As far as one can tell at this distance in time, the ownership interests were aboveboard, but Huggins and Connery were clearly in a conflicted position. Ruppert became so disenchanted with Connery over a couple of player transactions that he later overruled Barrow’s recommendation of Connery as the farm system director in favor of George Weiss.

The misses from St. Paul highlight another aspect of the Yankees scouting philosophy. The club recognized that scouting is an inexact science; a team needs to sign as many talented young players as possible because some will inevitably not live up to expectations. The Yankees were not only the most profitable team, but at least as importantly, the ownership did not pay out its profits in dividends; it reinvested them in the team. These recycled funds allowed the team to pursue and purchase the best players—and lots of them. For every Saint who didn’t pan out, the scouts landed a Lefty Gomez or a Bill Dickey.

As the team rebounded in 1926 with several of the players purchased from the high minors, Barrow continued to fine-tune his scouting staff. He brought in Gene McCann to help in the East and Johnny Nee to take over the South. Several years later the Yankees added the last of their legendary scouts, hiring Joe Devine to help out in the West. Like Barrow’s existing scouts, all three had spent time managing in the minor leagues. Minor-league managers were a good source of scouting talent for a couple of reasons. First, and most obviously, they had a chance to develop and hone their evaluation skills of young players. Second, and almost as important, they would have developed a network of amateur coaches and managers in the lowest minor leagues to whom they could turn for player recommendations. Many in these networks were considered “bird dog” scouts who would receive a small bonus when one of the players they recommended was signed.

With the onset of the Depression in the early 1930s, the minors looked for financial assistance from the majors. In response the majors changed the roster rules to make investing in minor- league franchises worthwhile. Under a wide range of circumstances players on a minor-league team controlled by a major-league team were now exempted from the 40-man roster limit. Ruppert quickly grasped the impact of this rule and ordered Barrow to establish a farm system. To stock what would quickly become the best minor- league system in the league, Barrow redirected his scouts to spend more time chasing top amateurs.

Landing the best amateurs required wits, money, salesmanship, and hustle. The Yankees scouts became renowned for selling the benefits of the Yankees organization to prospective signees. Given the depressed economic environment of the era, signing bonuses typically topped out at around $6,000 to $8,000. If the Yankees wanted a player, they would not lose him over money; Ruppert desperately wanted to win and would make funds available for players his scouts believed in. Of course the scouts did not completely forgo the high, independent minors. In 1934 the Yankees purchased Joe DiMaggio for $25,000 and five players, a discount price because of his reportedly bum knee.

On balance, the Yankees’ mystique and success on the field probably helped in the competition for prospects, but certainly some were afraid of getting stuck behind the Yankees stars. New York prep star Hank Greenberg chose Detroit in part because of his fear of getting stuck behind Lou Gehrig, although Barrow and Krichell were far from their best in the courting of the big first baseman.

The signings of Charlie Keller and Atley Donald were more the norm. Keller became a highly sought-after prospect while at the University of Maryland. McCann, who had been tracking Keller for some time, landed him for $7,500. Keller had always wanted to play for New York and likely signed for less than he could have received elsewhere. As a condition of his signing, the Yankees did agree to let Keller choose where he would start in the minors. Donald had also always wanted to play for the Yankees. His coach at Louisiana Tech sent a letter to the Yankees touting him, which Barrow ignored. (Barrow had received other letters from the coach plugging players and few had panned out.) To get a tryout, Donald rode the bus to St. Petersburg to meet the Yankees at spring training. He arrived early, ran out of money, and had to take a job in a grocery store. Eventually he cajoled Johnny Nee into giving him a tryout and the Yankees signed him.1

The Yankees scouts quickly proved their mettle in unearthing amateur talent. In 1937, for example, when the Yankees easily won the pennant and World Series, their top farm team in Newark won more than 70 percent of its games. This minor-league team, often considered one of the greatest ever, was led by many future major-league players and stars acquired by the Yankees scouts.

Over the years there have been many explanations of what the Yankees looked for in a prospect and why their scouts were so successful. In one of the more interesting, Paul Krichell once summarized the importance of a player’s makeup: “A scout has to look for real ability in a player: Has he got a good arm, does he have speed, does he take a good look at the ball? Temperament counts a lot but you can’t look inside a young player, can you? So, how well does he like to play ball? Does he really love the game?” He then went on to discuss some specific criteria: “Sometimes you can have a ballplayer who will do well in the majors with one fault. Earle Combs couldn’t throw. But he made up for that in many other ways. But if a kid has two faults, he doesn’t have a chance.”2

Notwithstanding Krichell’s quotation, none of the explanations are particularly compelling. After all, scouting methods and front- office organization are relatively transferable skills: Teams can hire scouts away from their rivals and organizational models can be readily duplicated. Furthermore, the very fact of all the explanations for the Yankees’ scouting success indicates there was no shortage of information regarding the Yankees system. In a competitive, reactive environment there is no simple recipe for success.

In the end the Yankees’ scouting success came down to two factors. First, organizationally and administratively the team created an effective organization: one that recognized the importance of scouting, provided sound strategic direction, gave its scouts the tools they needed to succeed, and demanded excellence from all personnel. Second, as a result of this organization, the team hired some of the greatest of all baseball scouts and kept them actively engaged finding and signing the nation’s best baseball prospects.

DAN LEVITT recently completed The Battle That Forged Modern Baseball: The Federal League Challenge and Its Legacy, to be published by Rowman & Littlefield under its Ivan R Dee imprint in the spring of 2012. He is also the author of Ed Barrow: The Bulldog Who Built the Yankees’ First Dynasty (Nebraska, 2008), a Seymour Award finalist, and co-author of Paths to Glory: How Great Baseball Teams Got that Way (Brassey’s, 2003), winner of The Sporting News/SABR Baseball Research Award. He lives in Minneapolis with his wife and two boys.

Sources

Online historical resources were extremely useful: in particular, The Sporting News and the New York Times. The SABR Scouts Committee “Who Signed Who” database is also a valuable resource for researching scouts. The author’s biography of Ed Barrow, Ed Barrow: The Bulldog Who Built the Yankees’ First Dynasty (Lincoln: University of Nebraska Press, 2008) offers a detailed history of the Yankees’ approach to team building, useful background on the Yankees’ scouting system, and an extensive bibliography of Yankees-related books and articles. The task of tracking down the many references to Yankees scouts in published sources was eased tremendously by The Baseball Index.

Notes

1. The Sporting News, January 4, 1940; The Sporting News, July 27, 1939.

2. Roy Terrell, “Yankee Secrets,” Sports Illustrated (July 22, 1957)