Dick Armstrong: Orioles PR Pioneer and His ‘Mr. Oriole’

This article was written by Bob Golon

This article was published in The National Pastime: A Bird’s-Eye View of Baltimore (2020)

Major league public relations (PR) practices evolved slowly during the first half of the twentieth century. In the early days, front offices had only a few employees, more resembling mom and pop businesses than the major corporations they are today. Teams today have entire departments devoted to public relations, community outreach, and media, but in the early part of last century, local newspaper writers often functioned as non-salaried ambassadors for the clubs, actively involved in both promoting and defending the game to the public.1 The effects of the 1930s depression and World War II forced the clubs to reevaluate their PR efforts in attracting fans back into ballparks. During the 1940s, clubs began using professional advertising agencies to this end, then gradually established in-house PR representatives to serve as a direct link between the clubs, the press, and the fans. By 1951, 14 of the 16 major league clubs had PR directors.2

Major league public relations (PR) practices evolved slowly during the first half of the twentieth century. In the early days, front offices had only a few employees, more resembling mom and pop businesses than the major corporations they are today. Teams today have entire departments devoted to public relations, community outreach, and media, but in the early part of last century, local newspaper writers often functioned as non-salaried ambassadors for the clubs, actively involved in both promoting and defending the game to the public.1 The effects of the 1930s depression and World War II forced the clubs to reevaluate their PR efforts in attracting fans back into ballparks. During the 1940s, clubs began using professional advertising agencies to this end, then gradually established in-house PR representatives to serve as a direct link between the clubs, the press, and the fans. By 1951, 14 of the 16 major league clubs had PR directors.2

Baltimore native Richard (Dick) Stoll Armstrong became the first PR director of Connie Mack’s Philadelphia A’s in 1950. The Princeton-educated 25-year-old attracted Mack’s attention while spending the 1947–49 seasons in the A’s minor league organization, first as a player and then as business manager of the Portsmouth (Ohio) A’s of the Ohio-Indiana League. A’s farm director Art Ehlers spotted business sense and leadership qualities in the young Armstrong, and in 1949 encouraged him to submit a proposal for the newly-established position of A’s public relations director. Armstrong got the job based on his vision for a golden jubilee celebration of Connie Mack’s 50 years with the A’s in 1950.3 J.G. Taylor Spink of The Sporting News referred to Armstrong as “a young man with ideas.”4 He became known for his innovative promotions for the otherwise downtrodden A’s.

Armstrong left the A’s in 1953 to accept a position as copy and plans director for the W. Wallace Orr advertising agency in Philadelphia. Even though he left the game, he never strayed far from it and continued assisting the A’s as their account manager with the Orr Agency.5

In late 1953, the majority owners of the Bill Veeck St. Louis Browns sold the American League club to a Maryland group led by attorney Clarence W. Miles. The triple-A Orioles were a successful minor league club, and their strong attendance convinced American League owners to award Miles the AL franchise in Baltimore for the 1954 season. Miles brought in Art Ehlers from the A’s as general manager, and Ehlers immediately knew he wanted Dick Armstrong as his PR director.6 Dick embraced the challenge of selling major league baseball to his hometown, and brought with him the same out-of-the-box creativity from his days in Philadelphia.

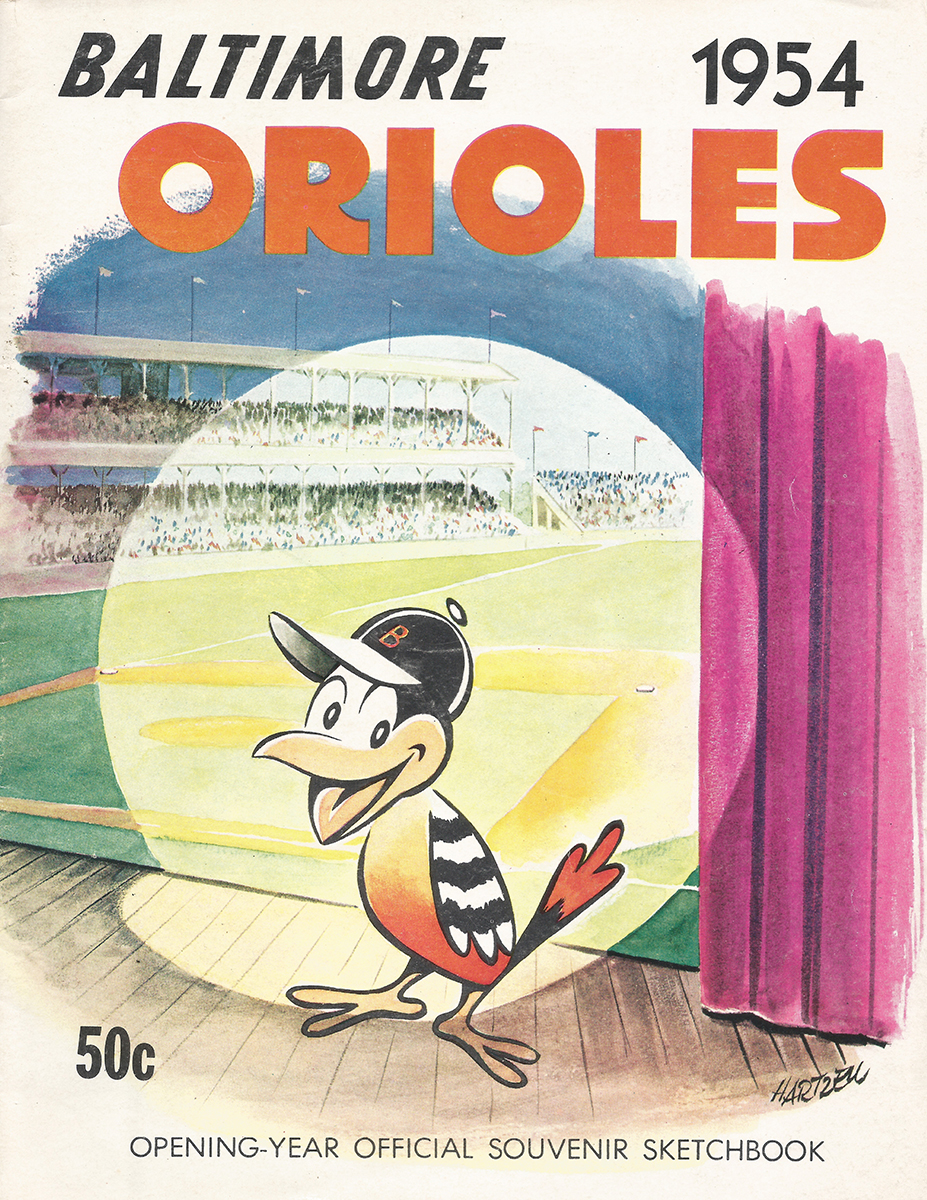

There was much to be done, including the design of promotional materials, ticket plans, and advertising strategies with the local media. Armstrong realized he needed a likable symbol to be used as a logo on team promotional materials. With the help of Baltimore Sun cartoonist Jim Hartzell, the original “Mr. Oriole” was born. “I was looking for a jaunty but likable bird, one with plenty of personality…and his perky bird face was quickly popularized,” Armstrong recalled.7 After Mr. Oriole appeared on the cover of the 1954 Orioles Yearbook, Armstrong took his smiling bird to a whole new level as baseball’s first stylized, in-stadium performing mascot — a forerunner of the mascots that became popular in major and minor league stadiums from the 1960s until today.

Armstrong wondered “if it would be possible to create a costume that would replicate the expression and appearance of Mr. Oriole so that a three-dimensional version of the bird could cavort on the field and in the stands during the games.”8 His long-time friend Johnny Myers knew a designer who used the cartoon Mr. Oriole as a model to produce an excellent costume likeness of the bird, complete with feathered wing stripes. Myers also happened to be an accomplished trumpet player with a natural stage presence, and Armstrong convinced his friend to dress in the suit and take his act to the ballpark.

“When the strikingly colorful bird made his first public appearance at Memorial Stadium following a proper introduction over the public address system, the fans went wild,” explained Armstrong, “but the piece de resistance was when he whipped out from beneath one of his feathered wings a trumpet, which he could play through his beak…the effect was sensational! We had the only trumpet-playing bird in captivity!”9

The original Mr. Oriole logo was drawn by Jim Hartzell of the Baltimore Sun. Dick Armstrong then created the major leagues’ first performing mascot via a costume based on Hartzell’s drawing. (BALTIMORE ORIOLES)

Around 2013, Armstrong contacted the Orioles office to inquire if they knew of the whereabouts of the Mr. Oriole costume. “Apparently, the costume disappeared along with many other invaluable materials…when the Birds moved to Camden Yards,” Armstrong recalled. “The person I talked with had never heard of Mr. Oriole. ‘Our mascot is The Bird,’ he declared, ‘He was hatched in 1979.’”10 Armstrong explained to the person that The Bird had a predecessor who was hatched in 1954.

The Mascot Hall of Fame in Whiting, Indiana, included The Oriole Bird in its Class of 2020 in June, and they have updated the historical record concerning his origins. “In the case of the Oriole Bird,” explains museum executive director Orestes Hernandez, “we recently discovered that he was introduced as the mascot of the franchise earlier than first thought. Previously it was thought Mr. Met was the first to have been introduced. The Bird has Mr. Met beat by a long shot!”11

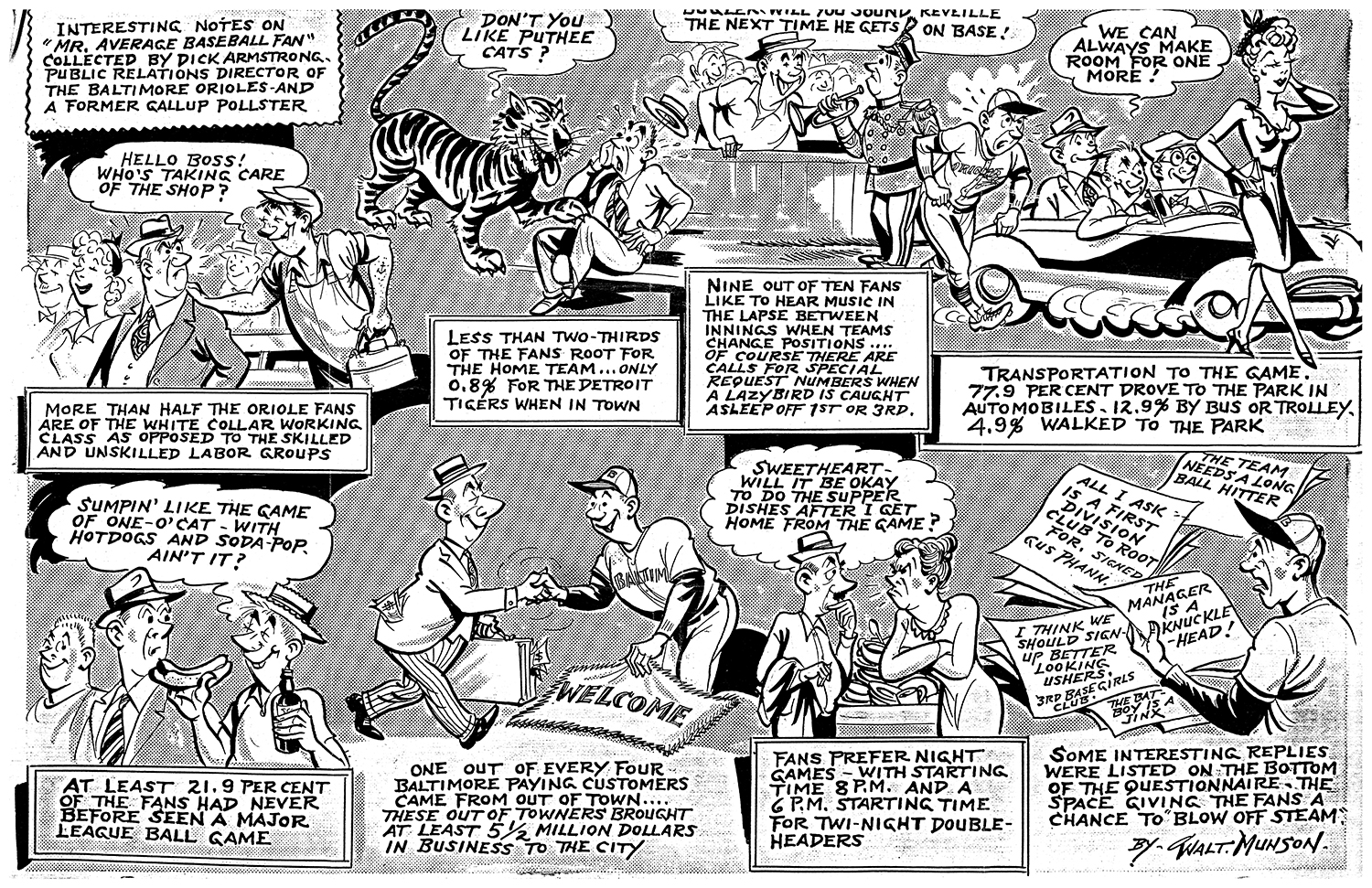

While concerned with entertainment and promotions for short-term fan appeal, Armstrong understood that the long-term viability of the Orioles franchise depended on a thorough knowledge of the fan base. Having studied scientific polling techniques at Princeton University, Armstrong knew research was a necessity.12 He had also worked for pollster George Gallup in 1948, polling presidential preferences in the New York area.13 Armstrong embarked on what was believed to be the first fan survey ever taken at the major league level utilizing scientific polling methods in 1954.14 Conducted at games during July and August, 2,500 questionnaires containing 19 questions were distributed; 2,400 were returned. Surveys were handed out to fans upon arrival at the park, and collected by the third inning, before the score of the game could influence fan responses.15

The results revealed some surprises about the average fan in the ballpark, chief among them that 26.1 percent of attendees came from out-of-town (as opposed to 5 percent forecasted prior to the season) and these fans contributed at least an additional $5.5 million to Baltimore’s economy in 1954.16

The findings and techniques of the survey were published throughout major league baseball and resulted in Armstrong receiving queries from a national audience.17 In The Sporting News, cartoonist Walt Munson devoted a multi-column spread to the survey results, and the paper opined in its editorial column that the “latest evidence of the Orioles’ wide-awake approach is the poll conducted by Publicist Dick Armstrong … the comprehensive nature of his questionnaire and the useful information by it seldom have been matched by similar endeavors.”18 Dick Armstrong established himself as a rising star in major league administration and his future in PR seemed secure.

But in 1955 Armstrong heard a different calling. During spring training at Daytona Beach that year, Armstrong received a personal calling to the ministry, which he described as his “Damascus Road Experience.”19 He left the Orioles at the end of the 1955 season to study at the Princeton Theological Seminary. Armstrong spent the next 60-plus years, until his death in early 2019, as a pastor, educator, author, and missionary in the Presbyterian Church. He was also one of the founding members of the Fellowship of Christian Athletes.20

Dick Armstrong never forgot his Baltimore roots, and was a life-long devotee of the Orioles. On August 8, 2014, the Orioles celebrated their 60th anniversary in Baltimore at Camden Yards, and Armstrong was invited to throw the first pitch as the only surviving member of the 1954 Orioles front office. Dick was proud to say, “I somehow managed to get the ball over the plate.”21

BOB GOLON is a retired manuscript librarian and archivist, Princeton Theological Seminary Library, Princeton, NJ. He also spent three years as labor archivist at Rutgers University Special Collections and University Archives. He is a member of the Mid-Atlantic Regional Archives Conference and past president of the NJ Library Association History and Preservation section. Prior to getting his MLIS from Rutgers University in 2004, Bob spent 18 years in sales and marketing for the Hewlett-Packard Company. A baseball historian and SABR member, Bob has been a contributor to numerous publications, can be prominently seen on the YES Network’s “Yankeeography – Casey Stengel,” and is the author of “No Minor Accomplishment: The Revival of New Jersey Professional Baseball” (Rivergate Books / Rutgers University Press, 2008).

Notes

1 William B. Anderson, “Crafting the National Pastime’s Image: The History of Major League Baseball Public Relations,” Journalism and Communication Monographs 5, no. 1 (2003) 12.

2 Anderson, “Crafting the National Pastime’s Image…”

3 Dick Armstrong, telephone conversation with Bob Golon, November 16, 2018.

4 J.G. Taylor Spink, “He’s Giving Young Ideas to Athletics,” The Sporting News, October 1950, article accessed from the Armstrong Collection, National Baseball Hall of Fame Library, Cooperstown, NY. BA MS 110, October 1, 2018.

5 Richard Stoll Armstrong, A Sense of Being Called (Eugene, OR: Cascade Books, 2011), 7.

6 Armstrong, A Sense of Being Called, 8.

7 Richard Stoll Armstrong, Minding What Matters (blog), “Mr. Met Was Not the First M.L Mascot!” May 4, 2012. Accessed at http://rsarm.blogspot.com.

8 Armstrong, Minding What Matters.

9 Armstrong, Minding What Matters.

10 Armstrong, Minding What Matters.

11 Mail from Orestes Hernandez, Executive Director of the Mascot Hall of Fame, Whiting, IN. January 27, 2020.

12 “Baltimore Polls Its Fans, Finds Only 65 Per Cent of Them Root for Orioles,” The Washington Post, January 6, 1955.

13 Herb Heft, “Armstrong Worked on 1948 Presidential Poll by Gallup,” The Sporting News, January 12, 1955.

14 “Baltimore Polls Its Fans…” The Washington Post.

15 Richard Stoll Armstrong, Baltimore Baseball Club Survey, 1954, (in-house publication) January 1955.

16 Heft, “Armstrong Worked on 1948 Presidential Poll by Gallup.”

17 Armstrong Collection, National Baseball Hall of Fame Library, Cooperstown, NY. BA MS 110, Box 4 Folder 3.

18 “Games $ Value to Community Shown,” The Sporting News, January 19, 1955.

19 Armstrong, A Sense of Being Called, 19.

20 Armstrong, A Sense of Being Called, 80.

21 Richard Stoll Armstrong, Minding What Matters (blog), “A First and Last Pitch,” May 2014. Accessed at http://rsarm.blogspot.com.