Felled By the Impossible: The 1967 Minnesota Twins

This article was written by Mark Armour

This article was published in The National Pastime: Baseball in the North Star State (Minnesota, 2012)

After a World Series appearance in 1965 and finishing second to the Baltimore Orioles in 1966, there were many reasons to believe the Minnesota Twins had a good shot at the American League pennant in 1967. Decades later, this remains one of baseball greatest and most historic pennant races.

On September 30, 1967, a Saturday afternoon, the Minnesota Twins played the first of a two-game season-ending series against the Red Sox at Boston’s Fenway Park. The Twins led the Red Sox and the Tigers (who had to play two doubleheaders) by a single game. A Twins victory would eliminate the Red Sox, while the Tigers had to win either three or (if the Twins beat the Red Sox in both games) all four of their games against the Angels.

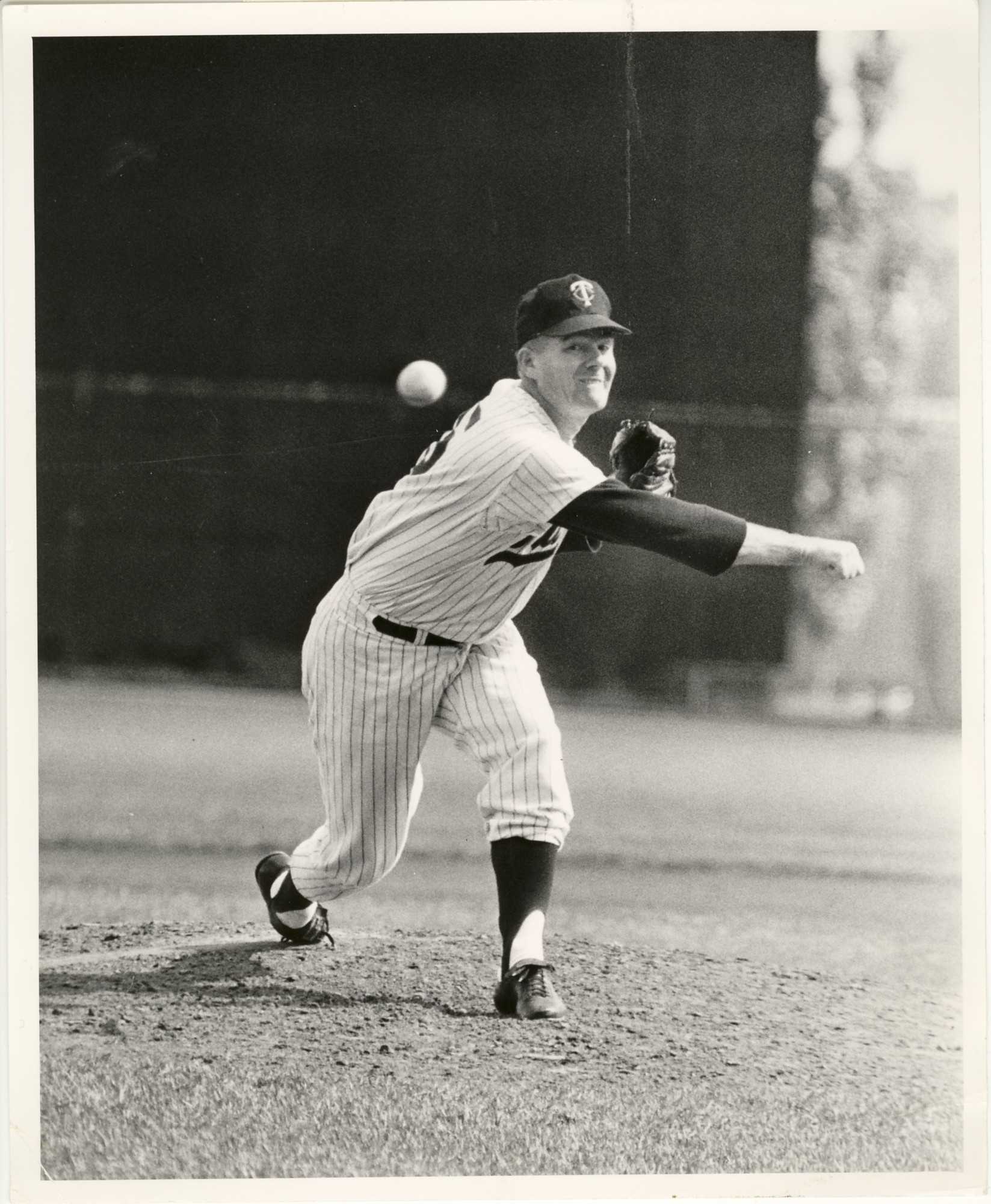

On the pitching mound for the Twins would be Jim Kaat, who had already posted a 7–0 record with a 1.57 ERA in 63 September innings. If he could win on the 30th, he would become just the second pitcher since 1946 (joining Whitey Ford) to win eight starts in a single month. The Red Sox would counter with Jose Santiago, making just his 11th start of the season. The Twins had 20-game-winner Dean Chance available on Sunday, but they had to like their chances to finish off Boston on Saturday. Of course, the season had been nothing if not unpredictable.

Heading in to the 1967 season many observers had conceded the pennant to the powerful Baltimore Orioles. After romping through the AL in 1966, the O’s had summarily swept the Los Angeles Dodgers in the World Series. The club had a few middle-aged stars—Frank Robinson (30), Brooks Robinson (29) and Luis Aparicio (32)—who had shown no signs of slowing down. The rest of the starting lineup was in their early 20s, and Steve Barber, at 28, was the old man of a deep and talented pitching staff.

Heading in to the 1967 season many observers had conceded the pennant to the powerful Baltimore Orioles. After romping through the AL in 1966, the O’s had summarily swept the Los Angeles Dodgers in the World Series. The club had a few middle-aged stars—Frank Robinson (30), Brooks Robinson (29) and Luis Aparicio (32)—who had shown no signs of slowing down. The rest of the starting lineup was in their early 20s, and Steve Barber, at 28, was the old man of a deep and talented pitching staff.

The toughest challenge, it was reasoned, would come from the Twins, who had won the pennant in 1965, finished second to the Orioles in 1966, and had as much front-line talent as any team in the league. The Twins were led by two star hitters—third baseman Harmon Killebrew, who had already won four home run titles, and right-fielder Tony Oliva, who had two batting crowns—along with a deep and flexible pitching staff.

The Twins regression in 1966—from 102 wins to 89—was completely due to a drop-off from their hitters. The team’s offense dropped by 111 runs, while their pitchers allowed 19 fewer runs, more than the league wide average drop of 11 runs per team. While Killebrew (39 home runs, 110 RBI) and Oliva (.307, 25 home runs) were among the best hitters in the league, no other regular was any better than league average for his position. Among many setbacks, shortstop Zoilo Versalles, the league’s MVP in 1965, dropped from 76 extra base hits to just 33 and provided very little offense from his leadoff spot. Meanwhile Jim Kaat won 25 games with a 2.75 ERA, and Mudcat Grant, Jim Perry, Dave Boswell, and Jim Merritt also provided solid starting pitching.

Right after the 1966 season, Twins manager Sam Mele parted ways with pitching coach Johnny Sain, an innovative thinker who got results from his pitchers but generally did not get along with his bosses. Sain demanded complete control over the pitching staff, a power his managers were usually reluctant to surrender. Jim Kaat in particular loved Sain, and in response to his mentor’s dismissal wrote a critical open letter to the Minneapolis Tribune. The letter ran on page one, and said, among other things, “If I were ever in a position of general manager, I’d give Sain a ‘name-your-own-figure’ contract to handle my pitchers. (And, oh yes, I’d hire a manager that could take advantage of his talents.)” Not surprisingly, these comments did not sit well with Mele. Twins owner Calvin Griffith, who acted as his own general manager, spoke with Kaat and mostly seemed bewildered that Mele could not get along with his coaches.1 Clearly the pressure was on Mele, and new pitching coach Early Wynn, to succeed in 1967.

Though the Twins had more pitching than hitting, this fact was largely misunderstood at the time due to the friendly hitting environment of Metropolitan Stadium. As an illustration, at the 1966 winter meetings the Twins traded Don Mincher and Jimmie Hall (likely their third and fourth best hitters), along with relief pitcher Pete Cimino, to the Angels for pitcher Dean Chance. After a brilliant 1964 season, Chance remained a good pitcher (12–17, 3.08 ERA in 1966), though not noticeably better than the five good starters the Twins already had.

To replace Mincher, Mele moved Killebrew to first base full-time (he had been playing there against left-handed pitchers), and returned Rich Rollins to full-time duty at third. To replace Hall, the Twins were counting on the return of Bob Allison from a broken hand, and were planning on playing the versatile Cesar Tovar in center field. With Earl Battey at catcher, the Twins hoped they could hit enough to make up for what they lost in the Angels trade.

On the mound, the Twins were set with Kaat, Chance, Grant, Boswell, and Merritt as starters, Jim Perry as the swingman, and Ron Kline and Al Worthington as the capable short relievers. It was a fine pitching staff, one of the best in the league.

When the season opened, the Twins played poorly for the first month. On May 15 Minnesota stood tied for eighth with an 11–15 record, 7 1?2 games behind the first-place White Sox. They could take solace in being tied with the defending champion Orioles, but the White Sox and Tigers (just one and a half games out) were good teams who were threatening to leave other clubs behind. Although there were many culprits, the biggest disappointments were Battey, Oliva (.183 through May 20), Jim Kaat (1–6, with a 6.66 ERA through May), and Grant (who lost his first three starts and was battling a sore knee).

The one Twins player who started the season hitting well was Versalles, hitting over .350 in early May and briefly among the RBI leaders. Unfortunately, this success proved fleeting, and his average steadily plummeted for the next five months until it fell to .200 at the close of the season. Versalles stayed in the lineup all year and provided a steady drain on the offense with a dreadful 52 OPS+. American League MVP just two years earlier, the 27-year-old Versalles was finished as an effective major league player.

On the other side of the keystone, Griffith had been an early proponent for the promotion of Rod Carew. “Carew can do it all,” said Griffith in March. “He can run, throw, and hit. He could be the American League All-Star second baseman if he sets his mind to it.”2 Pretty bold words about a 21-year-old fresh from the Carolina League. But Carew would fully justify Griffith’s confidence, and would do so immediately. Carew’s five hits on May 8 brought his average up over .300 for the first time, and he spent most of the summer among the league leaders. On June 15 his average reached .335, and he trailed only Al Kaline and Frank Robinson in the American League. It was therefore no surprise when Carew fulfilled Griffith’s prediction and started that summer’s All-Star game as a rookie.

The person most affected by the emergence of Carew was Cesar Tovar, who many observers felt would otherwise be the best all-around second baseman in the league. Tovar had won the job from Bernie Allen during the 1966 season, but with Carew on board Tovar was moved to center field to start the season. In the event, Tovar’s versatility and the struggles or injuries of many of his teammates caused the club to move him around the diamond repeatedly throughout the next few seasons. By mid-May of 1967 he’d already seen action at six positions. This likely did not help Tovar’s development, but he was a fine player, generally hitting at the top of the order and scoring 98 runs in 1967 (the third highest total in the league).

The person most affected by the emergence of Carew was Cesar Tovar, who many observers felt would otherwise be the best all-around second baseman in the league. Tovar had won the job from Bernie Allen during the 1966 season, but with Carew on board Tovar was moved to center field to start the season. In the event, Tovar’s versatility and the struggles or injuries of many of his teammates caused the club to move him around the diamond repeatedly throughout the next few seasons. By mid-May of 1967 he’d already seen action at six positions. This likely did not help Tovar’s development, but he was a fine player, generally hitting at the top of the order and scoring 98 runs in 1967 (the third highest total in the league).

Adjusting to the team’s slow start, Mele benched Battey in favor of Jerry Zimmerman, but the production from the catcher position remained inadequate. With Tovar moving to the infield to deal with slumps and injuries, Mele eventually played Ted Uhlaender full-time in center. He moved Jim Merritt into the rotation, turning away from Mudcat Grant. As for Kaat and Oliva, Mele kept playing them in hopes they would turn things around.

Meanwhile, the Twins managed to slog their way to .500 in mid-May and stay near that level for a few weeks. After a tough loss on June 8, when the Indians scored four runs in the ninth to win, 7–5, and drop the Twins to 25–25, Griffith fired Mele and replaced him with Cal Ermer, who had been managing their Triple-A club in Denver. The winner of four pennants as a minor-league manager, the 43-year-old Ermer’s major-league resume included a single game, in 1947, and a year as a coach with the Orioles in 1962. Griffith had expected the team to be contending for the pennant, not floundering in sixth place. After splitting their first 16 games under Ermer, the team got hot in late June and was back in contention by the All-Star break.

AL standings, July 10, 1967

| Chicago | 47-33 | — |

| Detroit | 45-35 | 2.0 |

| Minnesota | 45-36 | 2.5 |

| California | 45-40 | 4.5 |

| Boston | 41-39 | 6.0 |

With the Orioles nine games back, it looked to have turned into a three-team race, as no one expected either the Angels or Red Sox to be able to hang with the front runners.

One Minnesota player who revived at about the time of the Mele firing was Jim Kaat, who had publicly called out his manager the previous winter. Coincidence or not, Kaat had been 1–7 with a 6.00 ERA at the time of the switch, but won his first three starts and pitched as well as ever under Ermer. His victory on June 10 was the 100th of his career but came after nine winless starts. “There never has been any bad feeling of any kind between Sam and myself this year,” Kaat said. Either way, with Chance, Boswell, Merritt and Perry, the Twins had an excellent starting staff the rest of the season.

The biggest change for Harmon Killebrew in 1967 was that the club stopped moving him around the diamond to accommodate other players. With Mincher traded, Killebrew was a full-time first baseman for the first time in his career, and he responded with an excellent season, even by his lofty standards. It took him a few weeks to find his power stroke, but he hit 12 home runs in June on his way to 44, his sixth season over 40, and he coaxed a league leading 131 walks. Also important was the comeback of Bob Allison, after his lost season in 1966. Allison hit 24 home runs and provided valuable production hitting fifth behind Killebrew and Oliva. “This club definitely has the feeling we had in 1965,” said Killebrew.3

As quick as the Twins had gotten hot, they lost six in a row in mid-July, just as the Red Sox were winning 10 straight and getting into the thick of the race. At the end of July, the Twins were five games back and looking up at Chicago, Boston, and Detroit.

Tony Oliva was a remarkably consistent ballplayer over his first eight major-league seasons, but he never started slower than he did in 1967. Although Oliva’s hitting had steadily improved after his poor start, his average was still just .256 at the end of July. Fortunately, no one did more during the pennant race than Oliva, as he hit .333 the last two months with 6 home runs and 18 doubles.

Although Mele made changes to his lineup and rotation, Griffith did not make any moves to fix the holes on his club. The Red Sox picked up Jerry Adair, Gary Bell, and Elston Howard, all quality veterans who played a large role in the team’s pennant drive, and then signed Ken Harrelson as a reaction to Tony Conigliaro’s August eye injury. The White Sox acquired Don McMahon, Ken Boyer, and Rocky Colavito, and all were given important roles. The Tigers obtained veteran Eddie Mathews, and he played a key role down the stretch at both third and first base. With the closeness of the race and at least two poor hitters in the lineup every day (at shortstop and catcher), the Twins could have used another bat.

In early August, the White Sox went through their first rough patch of the season, and relinquished first place after two months at the top, the longest any team would hold the lead that season. All of the contenders went through a bad stretch at one point during the season, and as August ended it was difficult to separate the first four teams.

AL standings, August 31, 1967

| Boston | 76-59 | — |

| Minnesota | 74-58 | 0.5 |

| Detroit | 74-59 | 1.0 |

| Chicago | 73-59 | 1.5 |

The standings for every day the rest of the season were a slight variation of the above, with the teams dropping from first to third or rising from fourth to second regularly. No first place team would lead by more than a single game on any day hereafter. On September 6, there was a virtual four-way tie at the top.

The Twins held at least a share of the lead from September 2 through September 14, and looked to be the favorite when they went to Chicago to play three games. They lost all three, including a crushing defeat on the 16th when Dean Chance entered the ninth with a six-hitter but allowed three hits and his own error and ultimately lost the game 5–4. Just like that, the Twins were tied for third place. Never fear: a four-game sweep in Kansas City and they were back on top with eight games to go.

The Twins’ outstanding pitching continued in September, with their third straight month with an ERA under 3.00. For the season, the team finished at 3.14, second best in the league despite playing in a hitter’s park. The reason the Twins did not run away with the pennant was their imbalanced offense, a problem which only grew worse in the final month. In September, Killebrew, Oliva, and Allison hit .317 with 17 home runs. The rest of the team hit .216 with four round trippers. Still, a pennant was within reach.

It is interesting to note how Ermer used his pitchers in September. Beginning on September 9, the day after their final doubleheader, he used Kaat-Boswell-Chance-Merritt in rotation four straight times. After Kaat’s seventh consecutive September victory on the 26th gave the Twins a one-game lead with three to play, Ermer switched up and went with Chance on two days rest on Wednesday the 27th. Dave Boswell, who was passed over, had not pitched well in his previous start but had three complete game victories in September. Chance, who had won his 20th game on Sunday, could not get through the fourth on Wednesday, and the Twins dropped the game, 5–1. This was huge, but then again, weren’t they all?

In the latter stages of this great pennant race, the Red Sox had become the dominant story. Everyone loves an underdog, and while the other contenders had been good teams for several years the Red Sox had finished ninth in 1966 and had not really been in a pennant race since 1950. It was the Red Sox, and their star Carl Yastrzemski, who were featured on the cover of Life and Newsweek that September. Their loss of local favorite Tony Conigliaro to a brutal eye injury in August only heightened the drama of their story.

The Red Sox and Twins would have two days off to prepare for their two-game series, while the Tigers and Angels were rained out on both Thursday and Friday, necessitating consecutive doubleheaders over the weekend. The White Sox, who had led the race for more days than any other team, finally dropped out with their loss on Friday night. The remaining three teams all had a shot at winning the league outright.

AL standings, September 29, 1967

| Minnesota | 91-69 | — |

| Detroit | 89-69 | 1.0 |

| Boston | 90-70 | 1.0 |

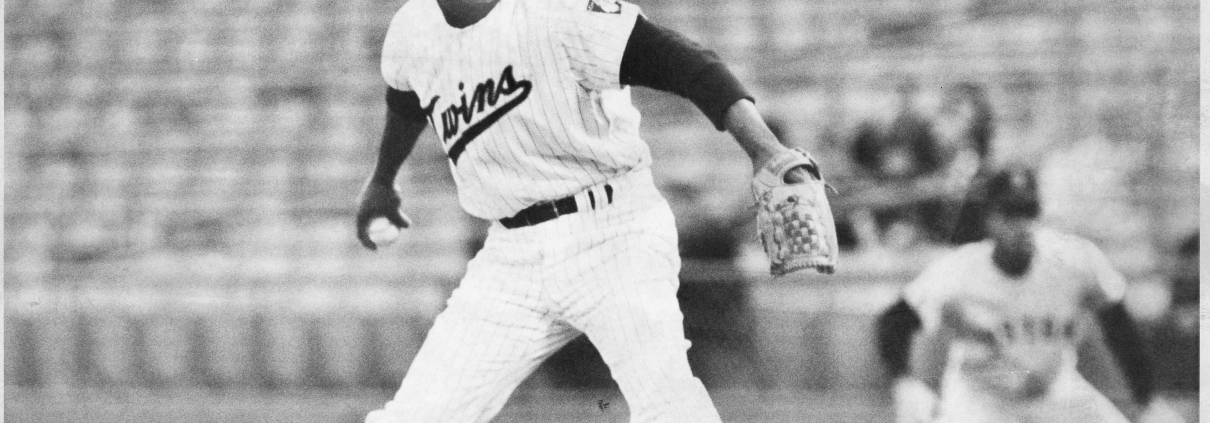

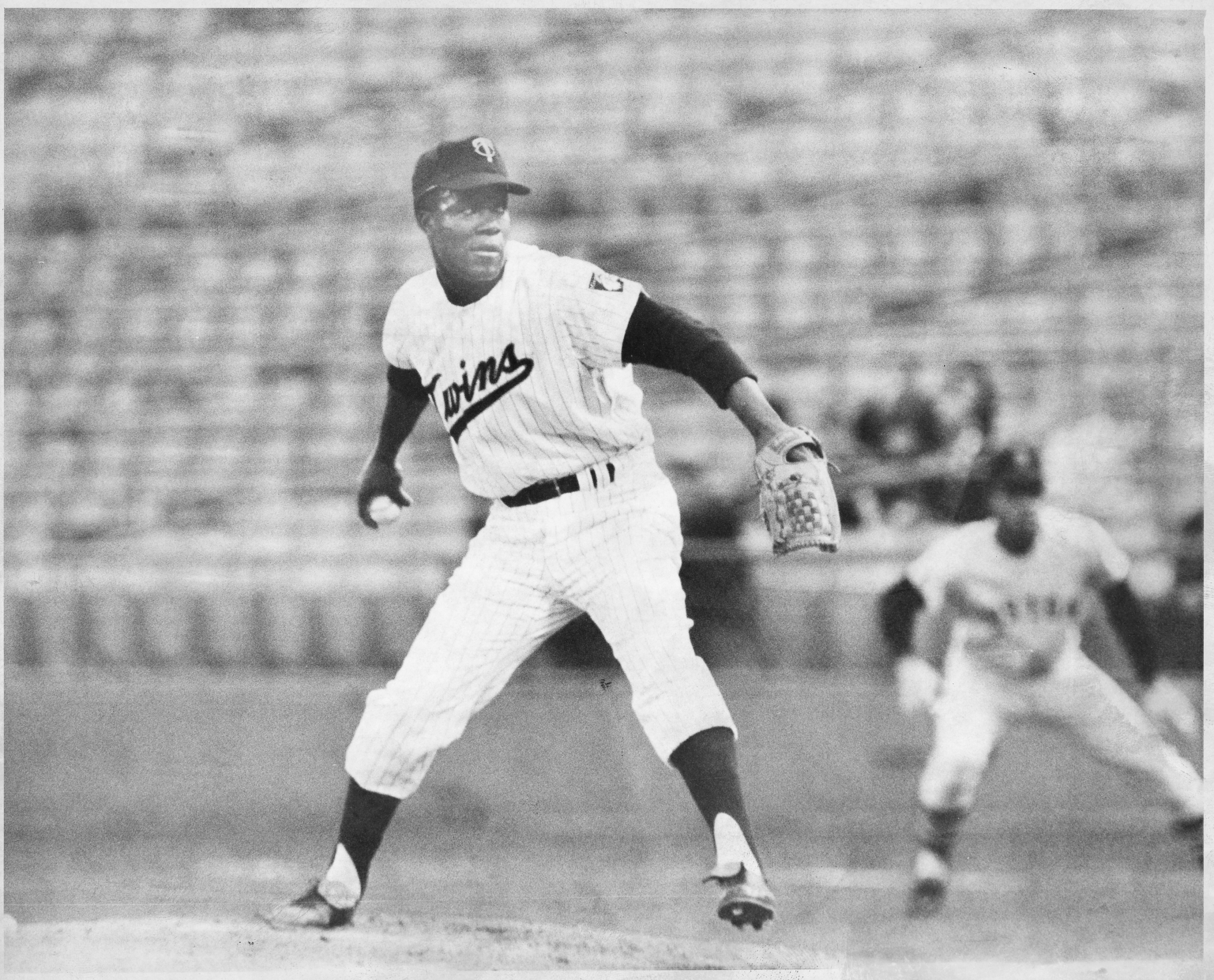

Though the final games would be played in Boston, the two days off allowed Ermer to pitch Kaat (with seven September wins) and Chance (20–13, 2.62 ERA, 18 complete games) on their regular three days of rest. Though just 28-years-old, Kaat had been a dependable workhorse for many years, averaging 17 wins since 1962, including 25 in 1966. For good measure, he had already won five Gold Gloves, and was one of the game’s top hitting pitchers (nine home runs in the past six seasons). He was the man the Twins wanted on the mound.

As it happened, Kaat got through the first two innings, and led 1–0 heading into the bottom of the third. While striking out opposing pitcher Jose Santiago to lead off the inning, Kaat felt a “pop” in his elbow and had to leave the game a few pitchers later, a game-changing break for the Red Sox. After throwing a heroic 66 innings over 30 September days, with a 1.51 ERA for the month, Kaat was done. A succession of normally excellent Twins pitchers—Perry, Ron Kline, and Merritt—failed to shut down the home team, and Killebrew’s 44th home run in the ninth was not enough as the Twins fell, 6–4.

Heading into Sunday, the Twins and Red Sox were tied, while the Tigers were a half game back with a doubleheader to play. If the Tigers swept, they would tie the winner of the game in Boston, necessitating a three-game playoff series beginning the next day. The Fenway matchup featured two 20-game winners—Dean Chance and Boston’s Jim Lonborg, both of whom had pitched Wednesday on two days rest and lost. The Twins seemed to have the pitching advantage—Chance had been 4–1 with a 1.58 ERA against the Red Sox, including a five-inning perfect game, while Lonborg had gone 0–3, 6.75 against the Twins.

The Twins scratched out unearned runs in the first and third innings, and led 2–0 after five. Chance had scattered four hits and looked to be cruising. Leading off the sixth, Lonborg dropped a perfect bunt down the third base line to reach first. Singles by Jerry Adair, Dalton Jones, and Yastrzemski tied the score, and the go-ahead run scored on a ground ball to Versalles that the shortstop elected to throw home rather than to second base to try for the double play.

Al Worthington came in and threw two wild pitches, Killebrew contributed an error, and suddenly it was 5–2, Boston. The Twins managed a run in the eighth, but lost the game and the pennant shortly thereafter. In Detroit, the Tigers dropped the second game of their twin bill, giving the Red Sox their miracle pennant.

Forty-five years later, this remains one of baseball greatest and most historic pennant races. Many books have been written about the season, most focused on the winning Red Sox. Looking back, it is obvious that none of the contenders was a great club. The Red Sox’ winning percentage was the lowest ever for an American League champion prior to divisional play. Each of the teams had notable flaws, and the three teams that fell short could point to a game or two that should have been won and could have made a difference. For the Twins, Kaat’s injury on September 30 is the most common lament.

On October 1 the Twins boarded an airplane which took them back to Minneapolis and 1,200 waiting fans. Cal Ermer promised the gathered faithful a pennant in 1968. “We’ve got to give Boston credit,” said Kaat, “but I think the best team and the best fans will be watching the Series on television.”4

MARK ARMOUR is the author of “Joe Cronin: A Life in Baseball” (Nebraska, 2010) and the director of SABR’s Baseball Biography Project. He writes baseball from Oregon, where he resides with Jane, Maya, and Drew.

Notes

1 Max Nichols, “Sain’s Exit Puts Mele on Win-or-Else’ Spot,” The Sporting News, October 22, 1966, 15.

2 Max Nichols, “Rookie Rod Carew Stakes Out Claim To Twin Keystone,” The Sporting News, March 25, 1967, 27.

3 Max Nichols, “Allison Regains Hot Touch With Stick— Harvest for Twins,” The Sporting News, August 5, 1967, 9.

4 “1,200 Greet Twins, Hear Ermer Promise 1968 Flag,” The Sporting News, October 14, 1967, 27.