Fenway Park’s Hand-Operated Scoreboard

This article was written by David Vincent

This article was published in 2006 Baseball Research Journal

On the evening of August 15, 2006, Nate Moulter and Mike Gavin arrived for work at Boston’s Fenway Park and started their evening by making a list of that day’s major league games with the uniform numbers of the starting pitchers. Then they turned to the main task of their job — posting information on the hand-operated scoreboard at Fenway Park. Nate and Mike are two of a three-man staff who work in the scoreboard during games. The 16-year veteran of the squad, Chris Elias, was away on business that night, but the board was ably manned by Mike, in his second year, and Nate, in his first season on the squad.

The left-field wall is one of the most recognizable features in any ballpark and has been a part of Fenway Park since it opened on April20, 1912. The original wall was a 37-foot-tall wooden structure, but that was replaced by a sheet metal wall in 1934 as part of renovations made by the new Red Sox owner, Tom Yawkey. A 23½-foot screen was built on the top of the wall in 1936 to prevent home run balls from damaging buildings across Lansdowne Street, which runs behind the wall. Commercial advertisements covered the wall as late as 1946, but they were painted over before the 1947 season by the distinctive green paint, which has led many people to refer to the wall in the last few decades as the Green Monster.

When the park was built in 1912, hand-operated scoreboards were the norm. Fenway Park, the oldest ballpark in the majors, still operates as it did in 1912, with a person posting numbers on the board as the game progresses. Now there are new fields that feature retro-effects, such as hand-operated scoreboards. Among these parks are Minute Maid Park in Houston and Coors Field in Denver. Chicago’s Wrigley Field, the oldest park in the National League, has a hand-operated scoreboard that was built in 1937, 23 years after it opened.

The Fenway scoreboard had sections for various purposes in the 1950s. In addition to an inning-by-inning section for the Sox game, there were sections showing the current score in all other major league games in progress. The National League section of the board was removed as part of a 1975 renovation, during which time the board was moved farther away from the left-field line toward left-center field. As part of that renovation, the sheet metal surface of the entire wall, which had been damaged by hundreds of baseballs striking it in four decades of use, was replaced.

The 1976 covering is still in place on the wall in 2006, with its own collection of dents from baseballs. In July 2002, commercial signs were added atop the wall, and before the 2003 season major changes were made. Those included removal of the screen and replacing it with a new section of seating called the “Monster Seats.” Those 274 tickets on the wall typically are the most sought after in Boston during the summer and provide a great view of the action and an occasional souvenir. Changes to the scoreboard in 2003 included the addition of a National League section, addition of the AL East division standings, and increased signage at either end of the scoreboard. Almost the entire 231-foot width of the wall is now covered with signs and the scoreboard.

Another feature on the scoreboard are the Morse Code initials of Tom Yawkey (TAY: dash, dot-dash, dash-dot-dash-dash) and his wife, Jean (JRY: dot-dash-dash-dash, dot-dash-dot, dash- dot-dash-dash). These vertical stripes appear just to the right of the Sox game section on the board.

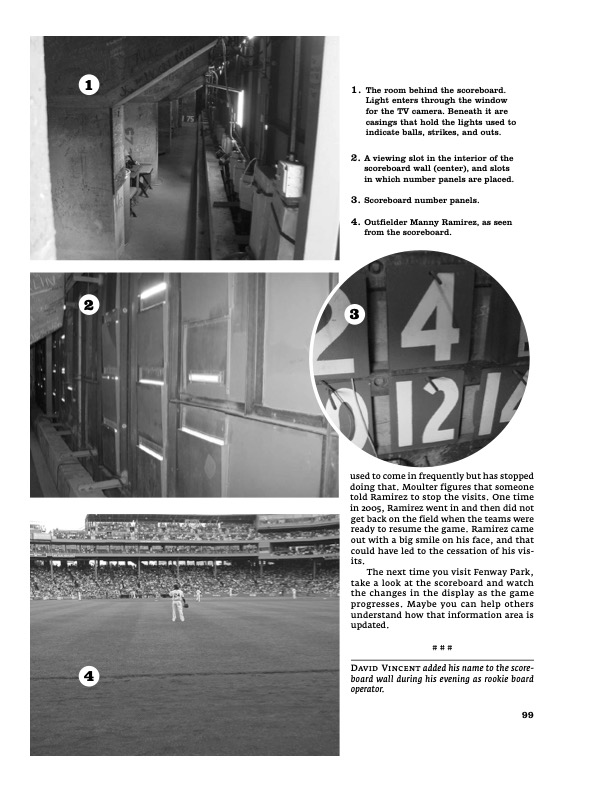

Behind the scoreboard is a small room that runs most of the length of the scoreboard. This is the “office” of Chris, Mike, and Nate, three guys with second jobs that many people in New England would love to have. This room has a concrete wall along the back with beams that run out toward the back of the metal scoreboard.

The concrete wall is covered with names of people who have come into the room through the years. Players, team officials, and others have memorialized their visit to this little room by writing their name somewhere on the concrete. Before the game this night, Nate pointed out the names of Wade Boggs, Trot Nixon, and model Leeann Tweeden to a visitor. Also on the wall are the names of Yankees GM Brian Cashman and Rockies Vice President of Communications, Jay Alves, among others. During batting practice, Magglio Ordonez of the Tigers visits the room with his son, Magglio, Jr. The younger Ordonez writes his name onto the concrete as his dad watches. The Tigers training staff also toured the small area behind the scoreboard, looking at names on the wall.

From this room the operators place metal number panels into slots for the Red Sox contest and the American League games. Since their room does not run as far toward the center-field end of the wall as the scoreboard, the National League scores must be put up from the front of the board. One of the workers runs out onto the warning track between innings with a ladder and places the numbers in the appropriate place on the scoreboard. Inside, there is a wooden step up to a small concrete wall just behind the scoreboard. Standing on the concrete, one can reach up to the slots to place numbers for each inning as the Sox game progresses.

The number panels used to indicate runs and hits are 16 by 16 inches and weigh three pounds each. The panels used for the pitcher’s numbers, innings, and errors are 12 by 16 inches and weigh two pounds. Each panel has a different number front and reverse; they are consecutive, such as 2 and 3. There are small slits into which the numbers are inserted from behind the board.

The slots for the number panels are similar to taking an inbox from a desk and placing it vertically against the scoreboard. Some of these are loaded from the top and some from the bottom. Each time the score changes in the Red Sox game, one team collects a hit or is charged with an error, one of the operators pulls the appropriate number out of its position on the board and either flips and reinserts it or takes a new number panel off the back wall and inserts that into the board. While an inning is in progress, the number of runs scored (greater than zero) are represented for that inning with a yellow digit, which is replaced with a white number at the end of the inning.

As the Red Sox game progresses through the first three innings, Mike watches an Internet site from a laptop computer for updates on scores from other big league games in progress. Occasionally, he yells out an American League score. Then one of the operators grabs a number panel off the back wall and moves to the correct slot in the scoreboard and updates that game’s score and inning.

Once the eight o’clock hour passes, many more games start and must be monitored. This means that there is more activity in the room as runs are scored in the Central Time Zone as well as Eastern. The current board display is kept on a notepad for comparison with the Internet scoreboard. The operators talk in their own code for out-of-town game scores. For each of those contests, there are two numbers for the pitchers, one for the inning and two more for the runs scored by the teams. When the score changes, someone might call out “3–0–1” for a game, meaning third inning with the home team ahead 1–0.

Keeping track of the Red Sox game requires looking through one of about eight slots in the scoreboard. These holes are approximately ten inches wide and one inch tall. From here, the operators can see the progress of the game as if standing in left field with Manny Ramirez. However, the view is restricted by the size of the slot; high fly balls can disappear from view and watching the fielder gives a better idea of what is going on. There is also a window in the wall between the words “Ball” and “Strike” that is used often by a television camera person. This vantage point offers a unique look as it is perfectly lined up with the baseline between first and second bases. Thus, one gets a great angle on a double play, in which the view is behind the throw to first base.

Fly balls that strike the metal scoreboard reverberate loudly in the room behind the wall. There is no running water, and therefore no toilet, thus left fielders who disappear into the room during a pitching change are not going in to relieve themselves, contrary to public belief. There is also no heat or air conditioning in the room, and it can get very warm during the hottest part of the summer as the sun beats off the metal facing of the scoreboard and heats the air in the room. No breeze relieves that heat as there is no possibility of cross-ventilation and little space in the wall for the breeze to enter. However, the board operators know that the temperature and lack of facilities is a small price to pay to work one of the coolest jobs in Boston.

Carlton Fisk hit one of the most famous homers ever at Fenway Park in Game Six of the 1975 World Series. As the ball flew down the left-field line, Fisk stood near home plate applying body English and waving with his hands, willing the ball to be fair as it reached the wall, and then leaped into the air when it hit the pole for a game-ending home run. This scene was captured accidentally by the television cameraman stationed in the scoreboard, as he had been instructed to follow the path of the ball but did not pay attention to that instruction since he was watching a rat at his feet, and kept the camera trained on Fisk and his gyrations, thus providing one of the most famous moments in World Series history.

In June 2006, board operator Nate Moulter’s face looking out the camera window appeared on ESPN and other television outlets. During a three-game series with the Washington Nationals, Alfonso Soriano, Washington’s left fielder and leading home run hitter, spent a few minutes during a pitching change talking with Nate at the window while leaning on the scoreboard. As Soriano started to leave, he said something and laughed, then swatted Nate with his glove and returned to his defensive position. Many left fielders have ducked into the room behind the wall during games.

According to Moulter, Manny Ramirez used to come in frequently but has stopped doing that. Moulter figures that someone told Ramirez to stop the visits. One time in 2005, Ramirez went in and then did not get back on the field when the teams were ready to resume the game. Ramirez came out with a big smile on his face, and that could have led to the cessation of his visits.

The next time you visit Fenway Park, take a look at the scoreboard and watch the changes in the display as the game progresses. Maybe you can help others understand how that information area is updated.

DAVID VINCENT added his name to the scoreboard wall during his evening as rookie board operator.

Click image to enlarge: