Forbes Field: Ahead of Its Time in 1909

This article was written by Robert Trumpbour

This article was published in The National Pastime: Steel City Stories (Pittsburgh, 2018)

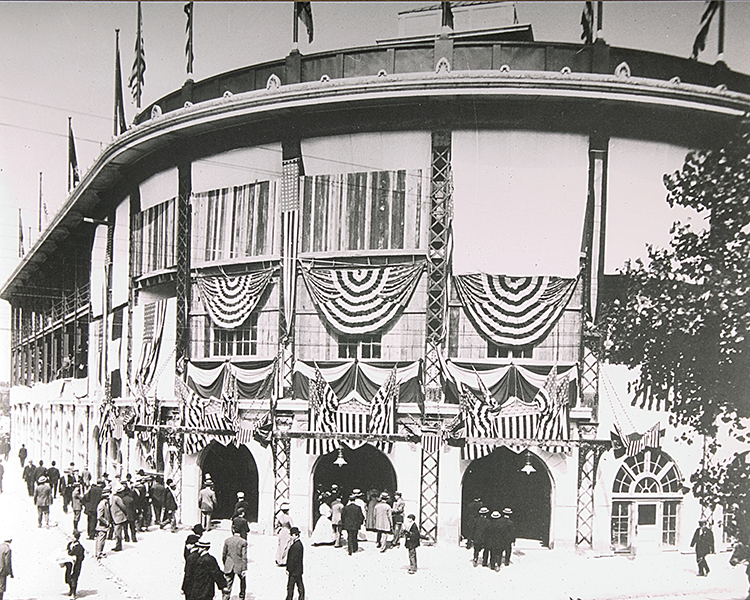

Forbes Field on Opening Day in 1909. (COURTESY OF THE PITTSBURGH PIRATES)

Many people regard Pittsburgh’s Forbes Field, home of the Pirates from 1909 to 1970, as a quaint, simple ballpark. Some might even consider Forbes Field’s design reflective of an old-fashioned and bygone era. Nevertheless, its construction was very much rooted in embracing modernity. Forbes Field inspired other sports entrepreneurs to embrace more permanent, luxurious, and ambitious projects. This led to the rise of increasingly opulent sports facilities throughout the nation.

Forbes Field and Philadelphia’s Shibe Park, both christened in 1909, were built to be permanent ballparks. Philadelphia Athletics owner Benjamin Shibe and Pittsburgh Pirates owner Barney Dreyfuss were the first major league owners to fully plan, design, and engineer ballparks that abandoned wooden construction in favor of facilities that were built entirely of fireproof steel and masonry. Forbes Field was the first ballpark to require a million-dollar investment, as well. However, it was not the first venue to embrace luxurious amenities.

In the 1880s, sporting goods entrepreneur and team owner Albert Spalding entertained Chicago White Stockings fans at White Stocking Park, offering well-heeled patrons enclosed private spaces that overlooked the field. These precursors to luxury suites included comfortable armchairs. Spalding even installed a telephone in his own private box. Ballpark historian Michael Benson described the facility as “the finest in the world” at the time. But it was a wooden structure, and like many nineteenth-century parks, it closed less than a decade after opening.1

Cincinnati’s Palace of the Fans opened in 1902 and continued a trend of hastily constructed opulence, as did New York’s legendary Polo Grounds, built in 1890. The Polo Grounds was then a wooden ballpark, while Cincinnati incorporated fireproof materials, masonry, and steel for much of the structure. Its Corinthian columns, palatial architecture, and opera-style private boxes looked impressive, but its uneven construction quality led to its demise in 1911, a mere 10 years after its unveiling.2

Philadelphia’s Baker Bowl is often called the first fireproof major league ballpark. Constructed largely of wood in 1887, it was quickly reconstructed of brick and masonry after extensive fire damage in 1894. However, some platforms in the rebuilt venue retained wooden support materials.3 As such, Shibe Park, also in Philadelphia, could be considered America’s first carefully engineered, fully fireproof baseball venue. Nevertheless, it contained wooden seats, as did other ballparks of the era. Produced at a cost of $315,248.69, Shibe Park was described as the finest American ballpark when it opened on April 12, 1909. It featured French Renaissance flourishes and was designed with an intended permanence not previously found in other American ballparks.4

Nevertheless, the scope and scale of Forbes Field’s construction dwarfed the highly touted project in Philadelphia. Forbes Field needed almost three times more structural steel and, with its million-dollar price tag, cost over three times more to build. In February, as work was underway, the Pittsburgh Post asserted that 537 large freight cars of materials would be required to finish the project.5 Forbes Field actually required approximately double that early estimate, including carload totals of 40 for ornamental iron, 70 for seats, 110 for cement, 130 for structural steel, and 650 for sand and gravel.6

An aerial view of Forbes Field in 1960. (COURTESY OF THE PITTSBURGH PIRATES)

To ensure that Forbes Field avoided the short lifespan of other ballparks, Dreyfuss solicited engineering and architectural expertise beyond what had been used elsewhere. On December 15, 1908, the Pirates announced that “numerous architects” had submitted plans for the proposed venue.7 After sifting through proposals, Dreyfuss hired Charles Wellford Leavitt Jr., a respected New York architect and civil engineer, to supervise the design. Leavitt worked on major projects for municipalities and wealthy clients, with his entry into sports having come through horse racing, with New York’s famed Belmont and Saratoga racetracks as clients.8 These venues featured large grandstands with opulent flourishes intended to attract wealthy patrons, making Leavitt’s transition to Pittsburgh’s ballpark design desirable.

C.E. Marshall, a Leavitt employee, provided further engineering expertise. Marshall’s years of site work at the Panama Canal shaped the early stages of that complex undertaking. Specifically, his knowledge of retaining wall construction and drainage was touted as construction began. Such a focus was likely by design, as Exposition Park, the Pirates’ home at the time, experienced numerous drainage and water-related problems.9

Site work began on December 23, 1908, shortly after the Nicola Building Company was announced as lead contractor. Before that, steel magnate and confidant Andrew Carnegie assisted Dreyfuss in property acquisition. As work began, Dreyfuss emphasized that although the ballpark was not located near Pittsburgh’s central business district, “We have not made any mistake in choosing the best site,” in part because the location was in an emerging upscale neighborhood, and, in part because the site afforded transportation options, including nearby trolley stations, that Dreyfuss said “are better than any other part of the city.”10

Forbes Field was unique in the level of publicity it received. Such attention reached beyond the predictably enthusiastic drumbeat of local newspapers. In one example, Harper’s Weekly offered a national feature that included panoramic photographs with coverage that emphasized its million-dollar cost while highlighting the location in “the Schenley district, one of the city’s most prominent residential sections.”11 Newspaper reporting was widespread, too. An Iowa newspaper, for example, explained that enthusiasm at the June 30, 1909, opening game was so intense that many of Pittsburgh’s downtown businesses “declared a half holiday,” while asserting police presence was required to quell “riots” caused by large crowds.12

The scale of the Forbes Field project and its focus on opulent modernity helped it to stand out among other ballparks. Even before planning and building Forbes Field, Dreyfuss was a baseball pioneer. He was an early proponent of postseason interleague play, with his Pirates facing the Boston Americans in the 1903 “World’s Championship Games.” He was an early adopter of the use of a canvas tarpaulin to keep Exhibition Park’s easily water-soaked infield dry, and he fabricated an even larger protective cover for Forbes Field. The Pirates were the first team to maintain a fully equipped training facility in the south, too.13 Subsequently, these strategies were emulated elsewhere.

Forbes Field’s innovations were numerous. As its grand opening approached, reporter James Jerpe asserted that “every detail at Forbes Field is many years ahead of the so-called modern effects and innovations elsewhere.” For example, Dreyfuss installed public telephones for use on all floors, a first for a major league-venue. He also created a separate entrance for “holders of season box admission tickets.”14

Luxury seating was not new, but Dreyfuss was the first to install elevators to comfortably transport patrons to their posh seating locations on the exclusive third tier. This precursor to modern skyboxes was described as “boxes for the true lovers of the game who are willing to spend a little extra money to not only obtain a fine view of the field, but to be able to secure a quiet and comfortable time.” For other visitors, ramps replaced stairways, allowing more convenient and efficient entry and exit.15

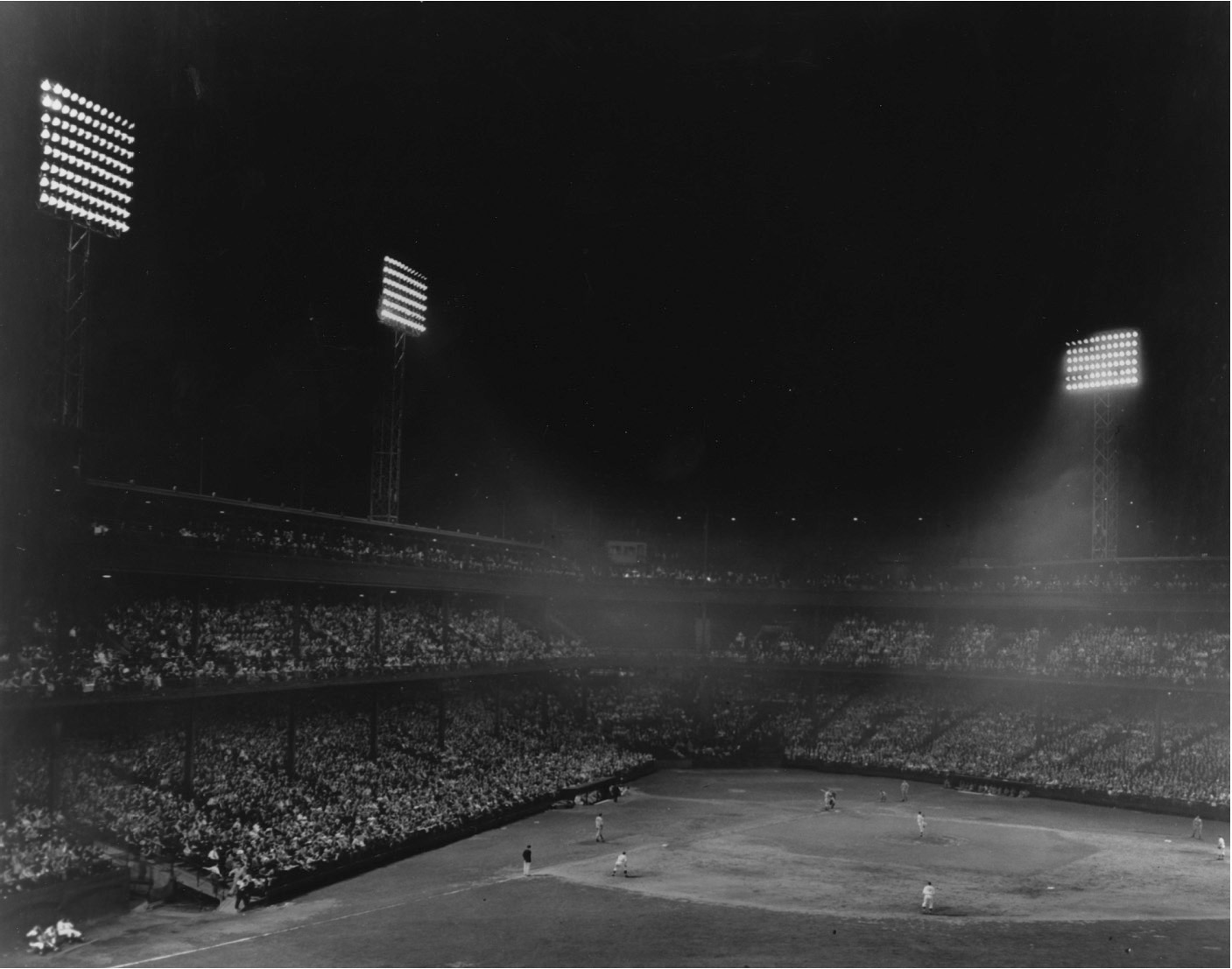

Baseball under the lights at Forbes Field. The Pirates began to play night games in 1940. (COURTESY OF THE PITTSBURGH PIRATES)

Less than six months after the first Ford Model T rolled out of a Detroit assembly plant, Dreyfuss planned for the installation of an expansive parking area underneath the ballpark.16 As the concrete was being poured, a Pittsburgh Post story explained that this part of the park “will be the finest automobile garage in Pittsburgh.”17

Dreyfuss also worked to astutely cultivate his most loyal customers. In one example, he installed brass identification plates on the private boxes of season ticket-holders.18 Additionally, men’s and ladies’ restrooms were more modern and comfortable than was available in other ballparks. Dreyfuss added private areas for umpires, too, as well as a separate entrance for players. The visiting team had access to locker rooms with similar space and amenities as the home team, including on-site laundry equipment. Electricity and lighting were installed, with early plans discussed for night baseball, even though such a game did not occur in Pittsburgh until 1940.19

Nevertheless, the lighting, electricity, and other amenities made Forbes Field a highly versatile all-purpose venue. In its opening week, Dreyfuss provided fans with baseball in the daytime, but after the game was over, a new group of patrons paid up to a dollar to watch evening fireworks while listening to a patriotic military band.20 When the team was on the road, events were scheduled, including a heavily touted extravaganza called the Hippodrome, a mix of circus acts, vaudeville, and popular culture.21 Football, boxing, and other entertainment took place, too.

Many considered Dreyfuss’s investment in Forbes Field foolish and overly extravagant, suggesting that he might never fill his cavernous new ballpark.22 The detractors were wrong, and the ballpark’s opening game unfolded in front of a massive crowd that exceeded capacity. Forbes Field attracted strong interest for the remainder of the 1909 season as the Pirates advanced to the World Series, and, in storybook fashion, beat the Detroit Tigers to be crowned world champions.

Barney Dreyfuss’s investment, persistence, and vision helped baseball to retain its stature as the national pastime at a time when the entertainment landscape was rapidly changing. Recently opened nickelodeons showcased films and relatively new commercial amusement parks such as nearby Kennywood Park in West Mifflin provided consumers with a broader array of leisure options than in previous generations.23 This uncertain environment presented unique challenges to sports entrepreneurs such as Dreyfuss.

The opulence that Forbes Field initially projected helped to attract numerous customers and, while doing so, altered the nature of the sporting experience in subtle and unexpected ways. Pirates shortstop Honus Wagner asserted that with a classier atmosphere, players needed to “stop cussing” during games, while Giants pitcher Christy Mathewson joked about the potential to lose fly balls because of shimmering diamonds in the stands.24

Of greater significance, rival baseball owners worked to emulate the success achieved at Forbes Field, with Albert Spalding boasting in 1911 that “there is nothing that can equal such baseball palaces as have been built in Philadelphia, Chicago, Cleveland, Pittsburgh, and other cities, to say nothing of the improvement contemplated in New York.”25 As other cities committed to new construction, New York rebuilt a fireproof version of the Polo Grounds in 1912, erected Ebbets Field in Brooklyn in 1913, and wrapped up baseball’s first concrete-and-steel era with the completion of cavernous Yankee Stadium in 1923.

For those unfamiliar with Pittsburgh’s baseball legacy, Forbes Field might not evoke the awe-inspiring, heart-pounding excitement of the much-ballyhooed Yankee Stadium, or perhaps one of today’s more modern twenty first–century ballparks. But after Dreyfuss died in 1932, National League President John Heydler recognized the transformative nature of Forbes Field. He displayed a picture of the crowded ballpark’s inaugural game directly opposite his office desk, and its careful positioning ensured that it would be an image that he would see every day. Neatly written below this large photograph was: “Forbes Field. June 30, 1909. Attendance, 30,332.”26 Forbes Field’s cultural and commercial success in 1909 paved the way for not only the House That Ruth Built, but numerous other majestic ballparks that would be unveiled throughout the twentieth century and beyond.

ROBERT C. TRUMPBOUR is Professor of Communications at Pennsylvania State University, Altoona College. He recently served as co-author of “The Eighth Wonder of the World: The Life of Houston’s Iconic Astrodome” (University of Nebraska Press), recipient of SABR’s Seymour Medal in 2017. Trumpbour also served as author of “The New Cathedrals: Politics and Media in the History of Stadium Construction” (Syracuse University Press). Prior to teaching, he worked in various capacities at CBS in New York for the television and radio networks. Trumpbour periodically does freelance production work on live sports broadcasts.

Notes

1 Michael Benson, Ballparks of North America (Jefferson, NC: McFarland, 1989), 82-83.

2 Robert Trumpbour, The New Cathedrals (Syracuse: Syracuse University Press, 2007), 75.

3 Michael Gershman, Diamonds: The Evolution of the Ballpark (New York: Houghton Mifflin, 1993), 57-59.

4 Rich Westcott, Philadelphia’s Old Ballparks (Philadelphia: Temple University Press, 1996), 106.

5 “Construction of New Ball Park at Pittsburgh Will Tax the Capacity of 537 Large Freight Cars,” Pittsburgh Post, February 28, 1909.

6 Gershman, Diamonds, 88.

7 “Plans Arrive for Park,” Pittsburgh Post, December 15, 1908.

8 “Charles W. Leavitt, Park Designer, Dies,” New York Times, April 24, 1928.

9 “Workmen are Busy at New Ball Park,” Pittsburgh Post, January 3, 1909.

10 “Grading of New Baseball Grounds to Be Finished Within Sixty Days,” Pittsburgh Post, December 23, 1908.

11 “Pittsburg’s Million-Dollar Baseball Park” Harper’s Weekly, May 22, 1909.

12 “New Ball Park Opened,” The Burlington (IA) Hawkeye, July 1, 1909.

13 “Fifteen Hundred Tons of Steel for Grandstand at Pirate Park,” Pittsburgh Post, January 29, 1909.

14 James Jerpe, “Forbes Field, the World’s Finest Baseball Grounds,” Pittsburgh Post, June 27, 1909.

15 “New Ballpark Will Surpass Expectations,” Pittsburgh Post, March 7, 1909.

16 “Major League Schedule Makers to Meet in Cleveland Tomorrow,” Pittsburgh Post, January 17, 1909.

17 “Two Shifts Will Work on New Baseball Park,” Pittsburgh Post, March 28, 1909.

18 “Pirates to Depart for Cincinnati,” Pittsburgh Post, May 9, 1909.

19 “Baseball Games by Electric Light Are Planned for New Pirate Park,” Pittsburgh Post, April 4, 1909.

20 “Fireworks at Forbes Field,” advertisement, Pittsburgh Post, July 4, 1909.

21 “Pittsburgh’s Hippodrome Is a Real Open-Air Circus,” Pittsburgh Post, August 6, 1909.

22 John Kieran, “The Passing of Barney Dreyfuss,” New York Times, February 6, 1932.

23 “Season Opens Today at Kennywood Park,” Pittsburgh Post, May 2, 1909.

24 Dennis DeValeria and Jeanne Burke DeValeria, Honus Wagner: A Biography (New York: Henry Holt and Company, 1996), 213.

25 Albert Spalding, America’s National Game (New York: American Sports Publishing, 1911), 505.

26 Kieran, “The Passing of Barney Dreyfuss.”