Frank Shaughnessy: The Ottawa Years

This article was written by David McDonald

This article was published in Our Game, Too: Influential Figures and Milestones in Canadian Baseball (2022)

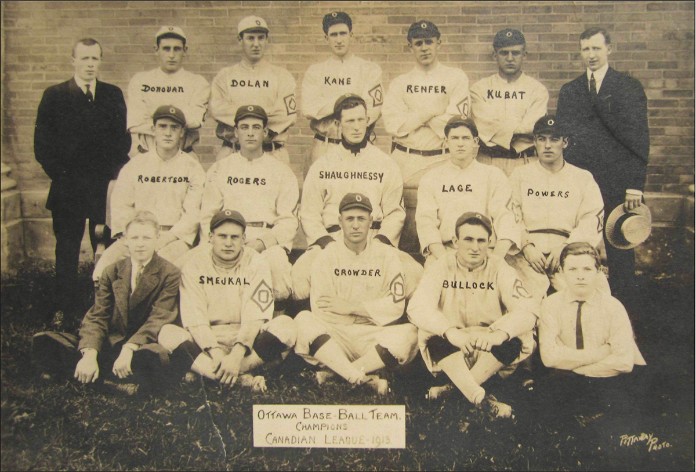

Frank Shaughnessy (middle, second row) guided the 1913 Ottawa Senators to their second straight Canadian League title, nosing out the London Tecumsehs by a single game. First baseman “Cozy” Dolan (top row, third from left) led the Senators with a .358 batting average. (Alfred Pittaway of Pittaway & Jarvis Photographers, Ottawa)

For Frank Shaughnessy, a lanky, copper-haired outfielder from small-town Illinois, the 1905 season was a crash course in the uncertainties of dead-ball era baseball. On April 17, a week and a half past his 22nd birthday, the former Notre Dame all-round athletic star had his first sip of big-league coffee, playing right field for the Senators in a game in Washington against the Highlanders of New York. He went 0-for-3 with a hit-by-pitch.

“It wasn’t easy in those days, believe me,” Shaughnessy said. “Regulars would actually chase a rookie with a bat if he attempted to take a turn hitting. A regular held his job until somebody drove him out, and every youngster was regarded as a menace.”1 Shag, as he was called,2 got into another game four days later, hitting a bases-loaded triple off future Hall of Famer Jack Chesbro. But the game – and Shag’s hit – were washed out before becoming official. The very next day Washington shipped him out, to the Montgomery Senators of the Southern Association.

Shaughnessy hated Alabama – the heat, the mosquitoes, the very real prospect of contracting yellow fever. He dropped 20 pounds, played poorly, and after seven games he was released, whereupon he packed his glove and spikes and headed north to Pennsylvania to play for Coatesville of the “outlaw” Tri-State League.3 After a few games there he ventured even further north to join the Montpelier-Barre Intercities, a.k.a. Hyphens, of the even more outlaw Northern League.4 It was already Shag’s fourth club of the year, and it was only June.

Frank Shaughnessy was born into a railroading family in Amboy, Illinois, about 100 miles west of Chicago, in 1883, the seventh child of parents from Limerick, Ireland. His father, Patrick, had emigrated to Canada as a boy. After an unsuccessful stint at farming near Montréal, he moved to the United States at the age of 25. Patrick held various positions during a 35-year career with the Illinois Central Railroad, including coal shed foreman and watchman. Two of his sons, William and John, also worked for the Illinois Central. Youngest son Frank was determined not to.

Smart, ambitious, and perpetually in motion, Shaughnessy worked in a pharmacy while attending high school. “I got up at six to open the drug store at seven, then ran three or four miles to school,” he recalled. “At noon I hurried back to the store to give the boss time for lunch, got my lunch at home about two blocks away, and dashed back to school. When school let out, I ran again to be at the store by 4 P.M. I got a half-hour off for supper, and, at 10 P.M., I could walk home. It’s no wonder I always could run fast – I had to!”5

Shaughnessy could also play baseball, which earned him a partial scholarship to study pharmacy at Indiana’s Notre Dame College, at the time “little more than a farm, and the nuns made our meals and washed our clothes.”6 Shag also excelled at track, and especially at football.7 In 1904 he captained the Fighting Irish.

“It seems like I can’t remember a time when I wasn’t working hard,” he said in later years. “While at Notre Dame, I also ran the campus newspaper, a confectionery concession and was the correspondent for several Chicago newspapers.”8 Using the nom de guerre “Shannon” to protect his collegiate athletic eligibility, Shag spent his summers playing professional baseball in outposts like Sioux City, Iowa, and Cairo, Illinois. In the spring of 1904 he finished his pharmacy degree and immediately began working toward another in law. It was after football season that fall that he came out as a professional athlete, signing with the Washington Senators.

FRANK AND KITTY

Shaughnessy’s glory days as a multisport star at Notre Dame were now behind him. His life had become a blur of steam trains, low-rent boarding houses, and cheap hotels. The only constant was the nagging worry that one’s current club – or even the whole league it was part of – might not survive the season, that the next paycheck might not materialize, that the opportunities to forge a career in the snakes-and-ladders, musical-chairs world of dead-ball era baseball might dry up.

The Northern, a colorful but financially shaky circuit based in Vermont and northern New York, was, in those days, the game’s answer to the witness protection program: a sanctuary for contract jumpers, collegians playing under assumed names, and those on the lam from Organized Baseball for a variety of legal, financial, and philosophical reasons.

Certainly, the caliber of play in the Northern was a lot better than one might have expected of a four-team circuit9 on the fringes of the American baseball map. The Hyphens’ pitching staff that season featured Shaughnessy’s former Notre Dame teammate Ed Reulbach (playing under the name Sheldon), who would go on to lead the National League in winning percentage three straight years, and Colby Jack Coombs, who would lead the American League in wins in 1910 and 1911. The third baseman on the team was Eddie Grant, who had a 10-year major-league career before being killed in France’s Argonne Forest in 1918.

The Northern was also the only integrated league in baseball – if the presence of a lone Black player, former Harvard baseball and football star William Clarence Matthews, counts as integrated. Matthews, putting up excellent numbers in Burlington, Vermont, was rumored to be headed for the National League’s Boston Beaneaters, whose manager, Fred Tenney, was eager to have him. When that opportunity failed to materialize, Matthews abandoned baseball and embarked on a prominent legal and civil rights career.

Baseball aside, the Northern League turned out to be the most eventful stop on Shaughnessy’s lengthy baseball odyssey. It was during this time he attended some sort of Roman Catholic function in Ogdensburg, New York, where the president of the Northern League introduced him to a young woman named Katherine Quinn, called Kitty. She was the convent-educated daughter of an Ottawa hotelier, Michael Quinn.10 That brief encounter might go a long way to explaining Shaughnessy’s decision to sign a $140-a-month contract to play for a Northern League expansion franchise in Ottawa the following summer. The manager of the new club – quickly branded the Outlaws – was Shag’s former Hyphens field boss, Arthur Daley. The Outlaws played their home games at the University of Ottawa’s Varsity Oval, where they drew respectable crowds of 1,000-1,500.

Once again the quality of play in the Northern was surprisingly fast. The Rutland team boasted future Hall of Fame second baseman Eddie Collins and right-hander Dick Rudolph, a 26-game winner for the Boston Braves in 1914. Burlington featured third baseman Larry Gardner, who would play 17 years in the American League. One of Shag’s Ottawa teammates, playing under the alias C.R. Ray, was Ray Demmitt, who had a seven-year career in the American League.

Shaughnessy acquitted himself well in this company, finishing with a .297 batting average and a league-leading five homers. He also proved a fan favorite. “Shaughnessy is the idol of the small boy and incidentally the ladies also,” said the Ottawa Journal “His appearance at bat is always the signal for an outburst of applause and kindly advice to slam it over the fence again or to murder the umpire when he calls a strike.”11

Despite its blaze of talent the cross-border Northern League proved no more durable than its 1905 iteration. Plattsburgh folded in midseason, then Rutland. On August 20, with the league down to three teams and the club nearly $6,000 in debt, the Outlaws, too, surrendered. Shaughnessy, manager Daley, and several more Outlaws had to sue to try to collect their final pay. It would not be the last time Shag would sit in a Canadian courtroom on a baseball matter.

While the league withered around him, Frank’s romance with Kitty blossomed. But with several weeks of summer left, Shaughnessy reluctantly hopped the train back to Indiana to try to squeeze a few more games and a few more dollars out of the remains of the season. He joined the South Bend Greens of the Class-B Central League, where he was said to have hit “the ball like a fiend,”12 batting .333 in 18 games. That fall – it was an era of distinct sporting seasons – Shaughnessy launched a backup career, coaching football at Welsh Neck Academy, a Baptist high school in Hartsville, South Carolina.

Frank and Kitty exchanged a lot of letters in those years. Shag spent the spring and fall of 1907 in South Carolina, where he coached baseball and football at Clemson Agricultural College. In the summer it was San Francisco, where he played left field for the San Francisco Seals of the Pacific Coast League. In 1908, after again coaching baseball at Clemson, Shag returned to Washington to join the D.C. entry in a wannabe third major circuit, the Union League. Sportswriters soon dubbed it the Onion League, “because it was cheap and smelled bad.”13 The Onion survived two months before landing on the baseball compost heap. Shaughnessy, though, landed on his feet – Connie Mack immediately signed him to play for his Philadelphia Athletics.

Kitty Shaughnessy, ca. 1908, the person responsible for Shaughnessy’s move to Canada. (Courtesy Honora Shaughnessy)

In his first game, in St. Louis on June 8, he went 3-for-4 against the Browns’ oddball future Hall of Famer Rube Waddell. But Shag’s bigleague dream lasted all of two weeks. “I thought I had a good chance with the A’s,” he recalled years later. “I was hitting .321 [sic – it was actually .310 on a team with a .223 batting average] after eight games and feeling pretty proud of myself. Then one cold day in Chicago, I had to make a hard throw to the plate and something snapped in my arm. I couldn’t throw overhanded for a year…”14

Mack promptly shipped Shag and his wounded wing to Reading, Pennsylvania, of the Tri-State League, now a Class-B circuit under the umbrella of Organized Baseball, for a player to be named later. That player turned out to be a young third baseman named Frank “Home Run” Baker, who went on to a Hall of Fame career. “That was a pretty good deal for the Athletics, I would say,” said Shaughnessy, adding, in faux-self-deprecating style, “I guess I wasn’t much of a player.”15 That fall 25-year-old Frank Shaughnessy, vagabond baseball player and football coach, married 20-year-old Kitty Quinn at St. Brigid’s, the English Roman Catholic church serving Ottawa’s Lower Town neighborhood.

A TEAM OF ONE’S OWN

In 1909 Shaughnessy bought his release from Reading so that he could take a job playing for – and, for the first time in his baseball career, managing – the Roanoke Tigers, a.k.a. Highlanders, of the Class-C Virginia League. He was the youngest manager in Organized Baseball. It was an auspicious debut. Shag batted .285 with a league-leading five home runs and guided his team to the pennant. It was a nailbiter of a finish – which would become something of a Shaughnessy managerial trademark – with the Tigers nipping the Norfolk Tars by just a half-game and .003 percentage points.

This cheery-looking bunch is the Washington entry in the short-lived Union League, a.k.a. Onion League, in 1908. Shaughnessy is in the middle row, second from left. Washington’s Toronto-born manager Arthur Irwin is the gentleman with the cookie duster moustache and the derby hat. Shag played well enough in Washington to be picked up by Connie Mack’s Philadelphia Athletics when the league folded in June of 1908. (Washington Times, April 18, 1908)

The Shaughnessys stayed put in Roanoke for another two years. The prospect of not having to pack up and move must have been appealing, especially with the arrival of their first two boys. (The family would eventually total nine children-eight boys and a girl.) It was also an opportunity for the indefatigable Shaughnessy to add to his gridiron résumé, as coach of the freshman squad at Washington and Lee College in nearby Lexington, Virginia, and to try his hand at a number of business sidelines. In Roanoke he bought into a couple of cigar stores, a garage, and an automobile agency, one of the first in the country.16 He also found time to pass the Virginia bar exam and hang out a shingle, although, according to legendary Montréal sportswriter Dink Carroll, Shag lacked the patience to build up a practice. As Maclean’s magazine once said, “Indoors irks this man.”17

On the surface Roanoke appeared a good fit for the Shaughnessys. But Kitty missed her family in Ottawa, and, equally, as a devout Roman Catholic, she never felt entirely comfortable in the Protestant South. Although the anti-Catholic KKK was between waves of activity during this period, Virginia was still the heart of Klan country. So Shaughnessy began to formulate a plan, one that would accommodate both his wife’s desire to raise a family in a more hospitable environment and his own to assert some measure of control over a perennially precarious baseball career. During his third and final year in Roanoke, he kept an eye on the fortunes of an upstart Class-D circuit operating in Western Ontario.

The 27-year-old Frank Shaughnessy made his managerial debut with the Roanoke Tigers in 1910, leading his team to the Virginia League pennant. (J. Harry Kidd, Roanoke, Virginia)

Consisting of teams from London, Hamilton, Brantford, St. Thomas, Guelph, and Berlin, the grandiosely named Canadian League had a moderately successful first season in 1911. Despite the failure of the Northern League in Ottawa, Shaughnessy felt the capital might be a good fit for this new loop. “Well, this always looked like one good ball town to me, and I am surprised you haven’t entered some league before this,” he had told an Ottawa reporter during a 1910 visit.18 The city in fact was reportedly the only one of its size in Canada or the United States that did not have professional baseball. Shag decided he would be the one to fix that. And so after the 1911 season, the Shaughnessys packed their bags, bundled up their baby boys, and boarded a northbound train, destination: Canada.

In Ottawa, Shaughnessy found a couple of partners among members of the fourth estate. They were Tommy Gorman, the 25-year-old Olympic lacrosse gold medalist turned “sporting editor” of the Citizen, and Malcolm Brice, 36, sporting editor of the Free Press. Publicity for the venture was not going to be a problem. Nor was money. A good chunk of the financial backing for the team came from Frank Ahearn,19 son of wealthy inventor and entrepreneur Thomas “Electricity” Ahearn, known as “the Edison of Canada.” The senior Ahearn was the principal owner of the Ottawa Electric Railway Company.

In December 1911 the Canadian League awarded a franchise to the Ottawa Baseball Club, Frank Shaughnessy, president (as well as part-owner, manager, and center fielder). The Peterboro (now spelled Peterborough) White Caps were also added for the 1912 season, making the Canadian an eight-team league and bumping it up, by virtue of the total population it represented – more than 300,000 – to Class C. Despite its elevated status, the league was hardly big business. In 1912 you could have bought the entire defending-champion Berlin club for $2,500. Team salaries – exclusive of the manager’s – were capped at $1,500 a month, although most teams played fast and loose with that notion.

TWO-TIMER

If building a team from scratch wasn’t challenging enough, two weeks after Ottawa landed its franchise came the revelation that the boss of the Senators was something of a baseball bigamist. Apparently, Shag had already signed a contract to play for and manage the Fort Wayne Railroaders of the 12-team, Class-B Central League. He might have gambled on Fort Wayne owner Claude H. Varnell not standing in the way of his new Ottawa venture, that Varnell would find someone else to conduct the Railroaders. He was soon disabused of that notion. “Shaughnessey [sic] will manage the Fort Wayne team unless he dies or gives up baseball,” Varnell responded.20

Undeterred, Shag persisted in his game of contractual chicken and spent the winter and spring months laying the groundwork for his Ottawa team’s debut. The first order of business was to negotiate a deal to play home games at Lansdowne Park. (Upgrades included the removal of a pesky fire hydrant in center field.) Season-ticket prices for 54 home games were set at $25 for grandstand seating and $15 for the bleachers. Advance, single-game tickets – 25 cents for general admission, 50 cents in the grandstand – would be sold through J.L. Rochester’s Drug Store on Sparks Street. The Senators also put out a call for men to supply “peanuts, cigars, chocolate and chewing gum”21 to the anticipated throngs at Lansdowne, where the team would play Monday through Saturday.

Sunday was another matter. No one played Sunday baseball in true-blue Ontario. A number of sites on the lawless Quebec side offered to host the Senators on the Sabbath, but Shaughnessy eventually bowed to unspecified pressures and shoved Sunday ball to a back burner. “Ottawas Have Yielded to Wishes of Better Element,” a Citizen headline said, without feeling the need to specify who exactly this better element was.22

But Shaughnessy’s most crucial task was to fill the Senators’ spiffy new maroon, black, and white uniforms with 14 capable bodies. As minor-league managers did in those days, he took out a few help-wanted ads in the sporting press. The response was encouraging. “Now that Ottawa is on the ball map, letters are coming in like answers to a patent medicine ad,” said the Journal.23 “Fast Men Coming Here from All Parts of United States,” said the Citizen.24 But by the end of March it had become abundantly clear that Varnell had no intention of divorcing his two-timing manager. Reluctantly Shaughnessy said goodbye to his family and left for Indiana, leaving veteran second baseman Louis Cook, a University of Illinois engineering grad, in charge.

Dampening the considerable excitement surrounding the baseball season in Ottawa was the news of an unfolding maritime disaster in the North Atlantic. In one of the great Dewey-Defeats-Truman headlines of all time, the Journal reported: “White Star Liner ‘Titanic,’ Largest Vessel Afloat, Crashes into Iceberg; 1300 Passengers Are Safe.”25 Among the casualties was Charles Melville Hays, the driving force behind Ottawa’s landmark Château Laurier, which opened a few days after the great ship went down.

Shaughnessy meanwhile was determined to make the best of his exile in Indiana by adroitly managing both ends of his predicament. Without kiboshing Fort Wayne’s chances in the Central League, he funneled a handful of reject Railroaders north to round out the Ottawa roster. Without this injection of talent it’s safe to say the Senators would not have challenged for the Canadian League pennant in their inaugural season.

Weeks earlier Shaughnessy had chosen Thursday, May 16 – Ascension Day and therefore a civil service half-holiday – for the Senators’ home debut. The city welcomed their 14 young Americans – there were no homebrews on the roster – with a civic luncheon, free tickets to the 1,500-seat Russell Theatre, a visit to the big horse show, and guest privileges at the YMCA. A flag in team colors flew over Sparks Street, a block from Parliament Hill. “Everyone is talking baseball,” said the Citizen.26

OPENING DAY

For the opener the Senators had arranged with the Ottawa Electric Railway Co. to lay on specially decorated streetcars. There would be a parade of automobiles, the band of the Governor General’s Foot Guards would play, a number of MPs would attend, Mayor Charles Hopewell would throw out the first pitch, and the Citizen would post out-of-town scores on big boards in front of the grandstand. Six thousand “fans” (still written with quotation marks in 1912) were expected.

But on Ascension Day the rain came down. And kept coming down into the weekend. Finally, on Saturday afternoon, “Jupiter Pluvius,” a.k.a. “Jup. Pluvius” or, simply, “Jup. P.” – the sports pages’ soggy euphemism for rain – let up long enough for the Senators to take the field against the defending champion Berlin Busy Bees (formerly Green Sox). Almost 7,000 fans, the biggest crowd in Lansdowne history save for the Central Canada Fair, jammed the park to watch the locals trounce the Berliners 7-1. In a bold marketing move, the Senators allowed 30 or 40 automobiles to park down the right-field line.

When it came to cars, the Senators were miles ahead of the pack. Before the advent of drive-in restaurants, movies, and even drive-in gas stations, the club, with an eye on the city’s ballooning automobile population (400 and counting in the spring of 1912) offered drive-in baseball – likely a first anywhere – at Lansdowne Park. Ticket-holders could chug right into the stadium and take in a ballgame without ever having to leave the comfort of their own flivvers. Shaughnessy, stuck in Fort Wayne, got to see none of this.

By mid-July, thanks mainly to their strong pitching, the Senators were solidly in first place. After an Opening Day loss to the Saints in St. Thomas, one of the Senators’ Fort Wayne loaners, right-hander Joe McManus, won 14 straight before finally dropping a 6-5 decision to Hamilton on July 16. After the game he confessed he’d been feeling poorly for a couple of days. A week later it was revealed that he had suffered “a light attack”27 of typhus, a common summer occurrence in Canadian cities of the day. McManus dropped 35 pounds from his 180-pound frame and was done for the season.

Even without him, the Senators kept winning. And on August 17, 1912, 4,500 fans – including about 60 motorists – packed Lansdowne to see the Senators clinch their first Canadian League championship. Second baseman Jimmy Louden scored the pennant-clinching run in a 2-1 win over the London Tecumsehs by beating out an infield hit, stealing second and third, and scoring on a wild throw. “Ottawa has gone baseball mad as the result of the team’s success,” said the Citizen.28 Another Fort Wayne castoff, lefty Frank “Cubby” Kubat, was the winning pitcher.

The Canadian League schedule ended on Labor Day with Ottawa nine games ahead of second-place Brantford. The Journal’s baseball writer typed this classic expression of postseason tristesse: “Louis Cook’s Senators have nearly all left town, the pennant will be purchased by the league, labelled ‘Ottawa’ and sent up by parcel post, and the season is ended so far as the city is concerned.”29

With the Canadian flag in the bag, Shaugh-nessy summoned Kubat (12-7) back to Fort Wayne, where the resurgent Railroaders, a last-place club as recently as July 1, were now in a tight pennant race with the Youngstown Steelmen. Kubat won a couple of key contests down the stretch, and the Railroaders finished on top by 2½ games. Shag, for his part, batted .304 and stole 34 bases. When it was all over, he sent a businesslike telegram to Kitty back in Ottawa: “Ft Wayne won the pennant. Had a hard battle we play Cleveland Wednesday at Ft Wayne expect to get home Friday phone Brice about pennant. Frank.”30 Somehow Shag had managed to parlay his divided loyalties into pennants for two teams in two countries in the same year.

Despite a shriveling Canadian economy, a soggy spring, a typhus outbreak, and a pennant race devoid of suspense, the Senators made about $1,000 on the season. Shaughnessy declared the Canadian the most successful minor league on the continent. Although at least 18 circuits across North America had lost teams or folded outright that summer, most observers expressed optimism about the future of the game in the capital. “This is sure a great ball town,” said right-hander Fred Herbert (16-9).31 “It is quite evident,” said the Citizen, “that baseball has come to stay.”32

After the season, Shaughnessy touched down in Ottawa just long enough to announce that he would not, as expected, be taking charge of the Roughriders football club. Instead he packed his whistle and reported to McGill University in Montréal, where he became the first professional coach in Canadian collegiate football. It was a move that led to Shaughnessy’s third sporting championship of the year – a Yates Cup33 win for his Redmen over the University of Toronto.

The title earned Shaughnessy a $500 bonus. And at a time when there was little, if anything, to choose between the collegiate and the pro game, it also earned his squad an opportunity to challenge for what was then formally known as the Earl Grey Football Cup. The coach declined, insisting instead that his players concentrate on preparing for upcoming exams. Shag coached at McGill for 19 seasons, during which time he helped define and refine the Canadian game.34

Now Shaughnessy, as a jock of all trades with a growing family, needed something to bridge the icy gap between football and baseball seasons. Although he knew next to nothing about hockey, he took on the job of coaching and managing Frank Ahearn’s Ottawa Stewartons senior amateur club in the Interprovincial Union. “I told them I didn’t know anything about the game and, in fact, hadn’t even seen hockey, aside from kids playing in the neighborhood rinks,” said Shaughnessy. “They insisted I knew how to handle men and organize sports, and that’s what they were interested in…”35 It was here that his string of sporting championships came to an abrupt end.

A BRAND-NEW SUIT

Shaughnessy might have continued his cross-border juggling act in 1913. He actually liked Fort Wayne – he even liked the club’s owner, Claude Varnell – and he really liked the idea of owning a club in one league and pulling in a good salary in another. Kitty, however, wanted him home, and this time Varnell agreed to release him for a reported $750 – a ransom deemed “a small fortune” by the Citizen.36

For spring training in 1913, Shag assembled more than 30 returning and prospective Senators in balmy Fort Wayne, where, should he have a position or two to fill, he had ready access to any surplus Railroaders. “It is the hardest thing in the world to rebuild a ball team shot to pieces in the major league draft. But fortunately we will have a small army of players to choose from,” said Shaughnessy, adding, “There are thousands of glittering stars in the bushes and we may be fortunate to pick up maybe one or two of them.”37

Among the no-shows at the start of training camp was Jimmy Louden, the promising young infielder who had single-handedly manufactured the run that won the 1912 pennant. Louden, who in civilian life was actually a University of Illinois electrical engineering student named George Kempf, was laid up due to complications from surgery to remove a facial tumor, allegedly the consequence of his having been struck by a pitched ball two years previously. Now word came from Chicago that Louden/Kempf had died. The cause of death was reported as “tuberculosis of the jaw.”38 There were rumors he’d been engaged to an Ottawa girl. He was just 21.

A subdued Ottawa team opened the 1913 season on May 8 in Brantford, where every store and factory in the city shut down for the day to allow their employees to take in the game. The Senators lost 8-7.

In the meantime, preparations were underway for the Senators’ home opener. A Sparks Street tailor, A.J. Curry, announced that he would present a $30 suit to the first Senator to hit a home run at Lansdowne Park. Curry’s offer seemed pretty generous, until you consider that Ottawa had failed to hit a single homer at home during its entire first season. Said one writer: “Any man to get credit for a four play wallop at the local ball yard [has] to sock the ball a quarter of a mile, more or less, and complete the circuit at a Ty Cobb clip”39 – which is exactly what Frank Shaughnessy did in his first game back in his adopted city since the demise of the Outlaws in 1906.

On Thursday, May 16, 1913, much of the federal government shut down at 1 P.M. so civil servants could get out to the ballpark in time to see Colonel Sam Hughes, the eccentric minister of militia and defense, throw out the first pitch. But mostly it was to witness Frank Shaughnessy’s debut as a Senator. As he stepped to the plate in the fourth inning, the game was halted so local MP Dr. Jerry Chabot could present Shag with a floral horseshoe wishing the team “Good Luck 1913.” After the interruption the pumped-up skipper drove the first pitch he saw over the head of the Brantford right fielder. The ball bounded up a slope and skipped toward the cattle barns near the Rideau Canal. Shag scored standing up. He finished the day with the Senators’ first-ever home-field homer, a single, a double – and a new suit.

In 1913 baseball was the hottest sporting ticket in the country. A record 24 Canadian cities fielded professional teams, and even in Ottawa, which had long been a lacrosse town in the summer, baseball was king. On Saturdays and holidays most clubs played morning and afternoon contests (no lights, no night ball) and charged separate admissions for each. On Saturday, May 24, for instance, the Senators drew several thousand fans for a morning game against Brantford and another 6,000 in the afternoon. This included the trendy occupants of 52 on-field automobiles – about 10 percent of the cars in the entire city.40 “Some of the most fashionable people in the city are regular patrons of the Ottawa ball club,” noted the Citizen.41

But the play of the defending champs was mediocre at best. In a game in St. Thomas, an increasingly short-tempered Shaughnessy charged in from center field to ream out the umpire, who happened to be an old nemesis of his from the Virginia League. During their discussion Shag bumped the ump. He was tossed and fined $5 on the spot. When he protested, the umpire upped it to $10. For once the skipper went quietly, apart from complaining afterward that the umps were out to “get him.”42

The Senators closed out May by dropping seven straight, which prompted Shag to blow up his club. He suspended one player, made some trades, and re-signed some of the previous seasons Senators who had failed to stick at higher levels. By mid-July, despite Shag’s hot hitting – after 33 games he was hitting .427 – the revamped Senators were still mired in fifth place. In St. Thomas an even testier Shag was charged by police after a run-in with a spectator, a hotel proprietor from Port Stanley, Ontario, named Joseph Coffey, for using abusive language with ladies present.

On the Senators’ next Western trip, Shag finally had his day in court. Senators and Saints alike packed the courtroom to hear the Virginia barrister argue his case. It was, said the Citizen, a “burlesque” of a trial.43 Witnesses testified that Coffey had called Shag “a big stiff,” and that Shag had retaliated by calling Coffey “a grey-headed old loafer.”44 Apparently, “loafer” trumped “stiff” in the insult arsenal of the day, and the judge, amid much hooting from the players, fined Shaughnessy $10.

“BIG, BOWLEGGED AND DOMINEERING”

A far bigger offense than Shag’s vocabulary, some said, was his Simon Legree management style – “more like McGraw’s than Mack’s,” as one baseball writer put it.45 It is a constant thread through his time in the Canadian League and, before that, in Fort Wayne and Roanoke. Described by the Hamilton Herald as “the big, bowlegged and domineering pilot of the Ottawas,” Shag was said to hand his men a raise one minute and a “blue envelope” (i.e., a pink slip) the next.46 “Shaughnessy’s methods are unpopular at times with the fans and with his players, but,” the London Advertiser conceded, “he gets results…”47 “All credit must be given to Shag,” said the London Free Press, “for he not only drives his players, never overlooks an opening, but he makes mediocre performers live wires.”48

One player who responded particularly favorably to Shaughnessy’s alleged heavy-handed style was Edgar “Lefty” Rogers, an Arkansas native acquired from Fort Wayne for $300. In Ottawa, Rogers created a buzz by virtue of being chauffeured to Lansdowne on game days by an attractive redhead in a white roadster – and even more of a buzz for what he did when he got there. Rogers had started as a pitcher but had been converted into an outfielder because of his lively bat. The Senators insisted on using him in both capacities. Behind Shaughnessy’s hitting, returning right-hander Erwin Renfer’s pitching, and a double-duty performance by Rogers, the fifth-place Senators took off.

On an early July homestand they won nine of nine to move into second place. On July 30 the Senators beat the Busy Bees 9-5 in Berlin to kick off another winning streak, this one of 13 games. On the August civic holiday they took two from Brantford to finally move into first place. Renfer’s win three days later was his 17th straight, and 20th of the season.49

The Senators continued to play winning ball for the final month, but they were unable to shake off the London Tecumsehs, under player-manager Rube Deneau, one of the few Canadian-born Canadian Leaguers.50 But whenever the Senators absolutely needed a win – as they did going into the final game of the 1913 season, having lost three straight to London and another to Peter-boro – Shag brought Rogers in from left field to pitch. And so on Labor Day afternoon, with the Canadian League pennant on the line, Lefty took the mound before 7,000 fans at Lansdowne Park and tamed the White Caps, 14-2.

The win enabled the Senators to snatch their second straight flag, this time by a single game over London.51 When Shaughnessy was presented with the obligatory floral wreath to mark the victory, he immediately hung it around his pitcher’s neck. For the season, Rogers, the Senators’ big-game player, won 13 of 17 decisions and recorded a .336 batting average. Senators first baseman and longtime Shag loyalist Frank “Cozy” Dolan52 also had a big year, batting .358, third best in the league. Center fielder Shaughnessy had a .340 average – eighth best – along with 37 stolen bases and two home runs. That performance, combined with his refuse-to-lose management style, may have made him the most valuable Senator in 1913.

In the fall Shaughnessy returned to McGill and bossed his Redmen to another Canadian intercollegiate title. And again, this time citing professionalism in the Interprovincial Rugby Football Union, they declined to go to the Grey Cup, eventually won by the Hamilton Tigers.

A NATIONAL PASTIME

By 1914, as historian Alan Metcalfe53 argues, baseball was Canada’s de facto national pastime. No other sport was growing as quickly – or as widely. In the summer of 1914 there were 19 Canadian-based professional teams spread across five minor-league circuits. The Canadian League was proving to be one of the more solid baseball ventures on the continent. In 1914 even the economically borderline Hamilton club was valued at $8,000, a far cry from the $2,500 asking price for the Berlin franchise three years earlier. Shaughnessy’s investment in the Senators looked promising. But baseball, along with everything else, was about to be severely tested by events in Europe.

For the new season two of the Canadian League’s smaller centers, Berlin and Guelph, were replaced by Toronto and Erie, Pennsylvania. With its larger population base, the Canadian moved up to Class B, which in those days was three rungs below the major leagues.

Meanwhile Shaughnessy faced the annual challenge of all minor-league managers of the day, namely, the scramble to piece together a club mostly of rejects from higher classifications. While the Senators trained in Chatham, Ontario, the skipper made his annual cross-border spring shopping trip. This time he came back with a couple of raw pitchers and a catcher/singer/ dancer named Eddie “Bowery” Wager, whose true ambition, it turned out, was to be a vaudeville star. When it became apparent Wager could hit the high notes better than the curveball, Shag was quick to give him the hook.

Shaughnessy had considerably more luck with a catcher turned pitcher, previously with the Windsor team of the Class-D Border League, with just 16 mound appearances at any level under his belt and a tabloid headline for a name. He was Urban Shocker, born Urbain Jacques Shockcor in Cleveland in 1890. In Ottawa everyone called him Herbie. Herbie Shocker would be the best player the Canadian League ever produced.

For their May 14 home opener the Senators hosted Canadian baseball legend Knotty Lee’s fledgling Toronto Beavers in front of 4,500 fans. “Clergymen, politicians, rail road magnates, civil servants, office boys, school children and people of every description were amongst the excited assembly that sat through two hours of rapid fire baseball,” reported the Citizen.54 Royalty, too.

The governor general, Prince Arthur, Duke of Connaught, and his 28-year-old daughter, Princess Patricia, of Light Infantry fame, watched the game from the royal limo, with the Ottawa bullpen corps of Shocker and Wager hanging around trying to explain what was happening on the field. It was decided to install a vice-regal box for next time.

Three days later the Senators, no longer willing to sacrifice potentially lucrative Sunday dates to the wishes of the capital’s “better element,” played their first-ever game in Hull, Quebec, just across the Ottawa River. Leading up to the 3 P.M. first pitch, special streetcars departed the Château Laurier every two minutes. More than 5,000 fans eventually squeezed into Dupuis Park, capacity 4,500. The overflow sat on the grass in front of the grandstand, and cars parked two deep down the left-field line. Toronto won 6-5.

While Sunday ball was a big hit with fans on both sides of the river, a watchdog group called the Lord’s Day Alliance decided to challenge its legality under federal legislation that, in essence, outlawed having fun in public on Sundays. The case charging Shaughnessy, partner Malcolm Brice, several Senators players, and the management of the London club with “conducting a certain performance on the Lord’s Day for gain,”55 would kick around Hull Police Court for more than a year.

Finally on August 6, 1915, Judge Goyette rendered his decision. More concerned with protecting provincial rights than advancing professional sport, Goyette ruled that the federal Lord’s Day Act could not be used to deprive Quebecers of the rights and liberties they enjoyed prior to its passage in March 1907. Sunday ball, he noted, had been a fixture of Quebec life for 30 years, and, since provincial law did not expressly prohibit such activity, the federal legislation was not applicable. Case dismissed, with costs. The long battle for Sunday ball had been won, at least in Quebec. It was soon eclipsed by a real war.

On Saturday, June 27, 1914, the Senators celebrated the raising of the 1913 pennant with a 3-2 win over Hamilton at Lansdowne Park, Shaughnessy again belting the Senators’ first home-field homer of the season to win the game in the bottom of the ninth. Shag’s heroics were reported on page 8 of the Citizen. Buried on page 12 next to an item headlined “Conservative M.L.A. Is Sued for Poker Debt,” was a dispatch from Sarajevo: “Austrian Heir Apparent and Wife Meet Death at Hands of Young Serb Student/May Seriously Affect European Peace.”56 It’s unlikely many baseball fans paid much attention to Balkan affairs, and the season continued pretty much as normal.

SPIT AND POLISH

By mid-July Shaughnessy had come to the inescapable conclusion that his sputtering team simply didn’t have the goods to catch archrival London, managed by former major-league pitcher and offseason dentist Carl “Doc” Reisling.57 But Shag, being Shag, was not about to roll over. “London’s lead is big,”- it had, in fact, grown to eight games – “but there’s plenty of time, and I’m confident I can overtake them,” he declared.58 He told the press he was willing to spend $5,000 if that’s what it took to turn his club around.

Skipping a series in Hamilton, Shaughnessy set off, checkbook in hand, on a scouting expedition to Michigan. In Adrian he caught up with Jack Mitchell,59 a hotshot 19-year-old shortstop whom the Senators had faced in a spring-training game. Shag went all in. The $1,000 he coughed up for Mitchell was reportedly the most ever paid for an infielder by a Class-B club. But, as one writer later noted, “This change put reverse English on the playing of the champions, and they inaugurated a winning streak seldom seen in organized baseball.”60 Mitchell more than justified his hefty price tag. He not only solidified Ottawa’s infield defense, he finished the season with a gaudy .344 batting average.

Shaughnessy made another key midseason adjustment. Novice pitcher Herbie Shocker had struggled to find a reliable breaking pitch. Shag suggested he experiment with a spitball. The day after Mitchell’s July 18 debut, Shocker unveiled his spitter in a Sunday game in Hull. He won, and pretty soon scouts from higher leagues were salivating over him. Thanks to the miracle of slippery elm, Shocker was on his way to becoming the pitcher who eventually won 187 games for the Yankees and the St. Louis Browns, before a fatal heart ailment ended his career – and his life – at age 37.61

With seven weeks to go in the season, the “Shagmen,” as the papers often called them, languished 8½ games behind London. But with Shocker and Mitchell leading the way, they went on a tear. On the August civic holiday the Senators took two one-run, extra-inning games from Hamilton. Shocker got the win in the second game with eight strikeouts in a three-inning relief stint. The gap with London now stood at 4½. Excitement over the improved play of the Senators was run over the following day by the real-world news that Canada had joined Britain in declaring war on Germany. Attendance cooled as the war heated up, but the Canadian League schedule proceeded without a hiccup. And the Senators kept on winning.

Mitchell continued his hot hitting down the stretch, and Shocker dominated, winning four games in a single week in August. On August 18 Ottawa beat Brantford 8-3 at Lansdowne to close to within half a game of the Tecumsehs. For this game the players had a new reminder of the gathering storm beyond baseball – soldiers camped around the edges of the outfield. “Hits into volunteers went for two bases only,” said one game report.62 The war had become a ground rule.

Shaughnessy responded by declaring the Senators’ August 20 match with St. Thomas a “Booster Day,” with all gate receipts save for the visiting team’s $75 guarantee going to the Hospital Ship Committee, headed by Lady Borden, wife of the prime minister. Both teams wore red crosses on their sleeves. The game dragged on for 11 innings and ended in a stalemate.

With a week and a half to go, the Senators traveled to London for a crucial series. They took three of four games to finally overtake the Tecumsehs after a chase of 57 days. “[T]he always-fighting ‘Shag’ never gave up and his stick-to-itiveness has resulted in him again topping the clubs and putting him on the road to the championship,” said the Hamilton Herald. “He’s a fighter, and it’s the fighter who wins.”63

LET’S PLAY THREE!

But it wasn’t over yet, and the battle again came down to the final day of the season. Following a remarkable 40-13 run, the Senators had claimed a precarious hold on first place with a record of 75-45 (.625). London, plagued by an inordinate number of rainouts, ties, and the illegality of Sunday ball in Ontario, sat at 69-43 (.616), two games but only .009 percentage points behind. What happened next was one of the most bizarre finishes ever.

Both clubs were scheduled to play a pair at home on Labor Day, the Senators against the sixth-place Peterboro White Caps, the Tecumsehs against the fifth-place St. Thomas Saints. A sweep would give Ottawa the pennant no matter what London did. That much was obvious. But beyond that, especially with a cold, low-pressure system blanketing the province from Western Ontario to the national capital, things got cloudy.

An Ottawa split and a London sweep, to consider one possibility, would hand the flag to Ottawa by the slimmest margin in baseball history, .6229 to .6228. On the other hand, a pair of Ottawa losses, coupled with a pair of London wins, would create a virtual tie atop the standings, but hand the pennant to the Tecumsehs on the basis of superior winning percentage, .623 to .615. The picture got even hazier if the dodgy weather were to wipe out one or both games in either city. And even more so when London manager Doc Reisling hatched a plan to play three games against the Saints on Labor Day, the extra contest ostensibly a makeup for an earlier rainout.64 A third game would provide Reisling with an extra piece in this most intricate of pennant endgames. If the Tecumsehs won three (.626) and the Senators were completely rained out (.625) or lost at least once (.620), London would squeak by.

In London the weather lifted in the morning, and the Tecumsehs beat the Saints 4-1 to move to within a game and a half of the leaders. In Ottawa the showers eased enough to permit the Senators to take the field against the White Caps. But in the second inning the skies opened up and the tarps rolled out again. Finally in early afternoon the rain in the capital subsided. Shaughnessy, knowing he had to win at least one game to guarantee the pennant, sent his groundskeeper out for a 20-gallon can of gasoline. It was sloshed over the soggy infield, and someone tossed a match in to burn off some of the damp. When the smoke cleared the umpire gave the go-ahead, and Shaughnessy’s prize discovery, Herbie Shocker, took the mound on one day’s rest in search of his 20th win of the season. Shocker delivered, and the Senators won 6-2.

Now, with Ottawa’s victory in Game 1, three things would have to happen for London to prevail. The rain would have to hold off in both cities, the Tecumsehs would have to beat the Saints for a second and a third time, and Peterboro ace Louis Schettler (20-12) would have to shut down the Senators in Game 2 in Ottawa. In the end, all three conditions were met: no rain, London victories in Games 2 and 3, and Schettler’s continued mastery of the Senators – and yet Doc Reisling’s gambit failed. What happened was this: After a couple of chilly and scoreless innings in Ottawa, Shaughnessy and Peterboro manager Curley Blount huddled, after which they persuaded the umpire to call the game on account of the cold. That snuffed any hopes of London catching Ottawa.

“In view … of the fact that Frank Shaughnessy and his Senators have come from behind within four weeks and have overhauled London’s ten game lead, no one will dispute them the honours,” said the Citizen.65 Well, not exactly no one. “Probably the Cold Was in Shaughnessy’s Feet,” said the London Advertiser. “Maybe it was too cold to play ball and maybe it wasn’t, but, at any rate, it is a peculiar fact that the cold was not noticed until after the second game had been started.”66

The London Free Press concurred, complaining about the appearance of “fix up baseball” in Ottawa. The cancellation of Game 2, they surmised, came only “upon the discovery of what a loss to Peterboro in the second game meant.”67 The London Advertiser nonetheless paid Shaughnessy grudging respect, which was the type of respect he typically received: “Shag is a foxy boy and if you want to win any pennants from him you have to sit up nights and dope out a fancy line of stunts to get ahead of him.”68

Whether the cancellation of the second game was due to Shaughnessy’s cunning or simply to a confluence of cold weather and dumb luck is not known, although it is difficult to imagine that the skipper wasn’t fully aware of all the permutations and combinations on that day, and catching a telegraphic whiff of a third game in London, decided to quit while he was ahead. Regardless, Shaughnessy and the jubilant Senators adjourned to a hotel to get warm and celebrate. The Shagmen had won 42 of their final 55 games to grab a third straight pennant for Ottawa. For London it marked the second straight season with no cigar – the Tecumsehs’ cumulative margin of defeat, .006 percentage points.

Shaughnessy himself had another strong season in 1914. In 119 games he batted .289 with 37 stolen bases and a team-leading six homers, half of them coming in a May 31 game at Dupuis Park, when he blasted three over the short left-field fence. But perhaps his most significant contribution to Ottawa’s success was his indomitable personality. “The continued success of this shrewd Irishman smashes all idea of luck,” said one baseball writer. “That commodity might land him a winner once, but when success is spoiled on success there is something in the man himself above ordinary.”69

Organized Baseball, on the other hand, did not have a good season. The editor of Sporting Life designated it “the universal wreck of the minor leagues.”70 43 minor leagues started the year; 36 finished in some form or other. Organized Baseball, involved in a territorial war with the upstart Federal League, had spread itself perilously thin. Too many clubs made too little economic sense, especially in the second year of a North American economic recession. Erie, for example. Erie, in the words of Sporting Life’s London correspondent, “did not draw as much as a soap spieler at a hobos’ picnic.”71 And then there was the exploding war in Europe.

Despite the nailbiter of a pennant race and a Canadian League monopoly on Sunday ball, attendance at Senators games reportedly took a 40 percent attendance hit over the final month of the season, and the club reported a $2,700 loss. Shag’s gamble on baseball in the capital was starting to look a little less sure.

In the fall of 1914, Shaughnessy again coached at McGill. Over the winter he made his debut as “business manager” of the other Ottawa Senators, those of the National Hockey Association, the forerunner of the NHL. Shaughnessy courted local football and hockey star Eddie Gerard by plopping $400 cash on his desk and telling him he could walk out with it if he signed a contract on the spot. Gerard did and scored in his first game, a 4-3 win over Quebec. That spring Shag came close to adding his name to the Stanley Cup, but the NHA-champion Senators dropped the final to the Pacific Coast Hockey League Vancouver Millionaires.

TO SHREDS

In 1910, the peak year for minor-league baseball until after the Second World War, there were 50 leagues in operation. By the spring of 1915, the number was down to 32, only 23 of which staggered through the season. A no-frills, bargain-basement, six-team, Class-C Canadian League was one of them. So stripped down were the teams that star pitcher Herbie Shocker was assigned to prepare the diamond for the Senators’ abbreviated spring training in Chatham.

But few paid much attention to the petty concerns of baseball. In the spring of 1915 Prime Minister Robert Borden was contemplating conscription. Young Canadians were being gassed at Ypres. On May 7 a German U-boat torpedoed the Cunard liner Lusitania off the coast of Ireland; 1,193 passengers and crew were killed, including 128 Americans.

Frank Shaughnessy knew nothing about hockey when he settled in Ottawa in 1912, but two years later he was the business manager of the 1914-15 National Hockey Association champion Ottawa Senators. (George T. Wadds, Photographer, Ottawa).

The Senators, hobbled by injuries and hampered by a barebones roster, got off to their usual sluggish start. By the King’s Birthday holiday, June 4, they were mired in fifth place, and for the rest of the month they hovered around .500. But in July they took off. They played at a .705 clip for the rest of the way, leaving 1915 pretenders Hamilton and Guelph in the dust. The season played itself out without much excitement, the Senators eventually stretching their lead to 12½ games over the wilted Maple Leafs of Guelph. “…Ottawa had the championship clinched so early this year that the enthusiasm fell to shreds,” said the Citizen.72 Attendance dropped by half.

Shaughnessy had yet another strong season at the plate. He batted .295 with three homers and 30 stolen bases in 101 games. He had now finished no worse than third in all seven years of his managerial career, winning five flags in three different leagues. His teams had played .597 baseball during that span. Shocker, meanwhile, tossed 303 innings and won 19 games. He was snapped up by the Yankees, who paid Ottawa a $750 draft fee.

In an attempt to further bolster the team’s bottom line, Shaughnessy arranged a series of well-attended matches in Ottawa against a couple of barnstorming Black teams, the Cuban Giants (actually out of Buffalo, New York) and the Havana Red Sox (from Watertown, New York). The Senators held the Giants to five runs over the course of a five-game sweep, and then took three of four from “Havana.”

That fall Shaughnessy coached football at McGill, but also moonlighted with the Ottawa Roughriders of the Interprovincial Rugby Football Union (the “Big Four”). In the winter he again acted as “business manager” of the hockey Senators, who would finish second in the NHA, well back of the Montréal Canadiens.

His baseball future, however, remained uncertain. The rumors and the speculation – about the Senators, about Shaughnessy, about the future of minor-league baseball itself- swirled all fall and winter: Shag would manage Toronto in the International League. Or maybe a team in the upstart Federal League. The Senators would replace Richmond in the International League. Or they would join the New York State League. Or maybe there would be another iteration of the Canadian League, which might or might not include Ottawa.

FROZEN IN TIME

On Valentine’s Day 1916, the Parliament Buildings burned down. It would serve as an apt metaphor for Ottawa baseball that season.

In March St. Thomas resigned from the Canadian League. The remaining clubs debated the wisdom of carrying on, but the discussion ended when a new battalion, the 207th, moved into Lansdowne Park in April. There was now no place for the perennial champion Senators to play. And with that, the team and the league suspended operations for 1916. It never resumed. The Senators’ peerless record- four seasons, four pennantsremains frozen in time. “People will feel lost without league baseball in Ottawa and Hull this year,” mourned the Citizen. “About July 1 fans will begin to sigh for the good old days when London and Ottawa fought it out in a neck and neck race for the Canadian League pennant.”73

Shaughnessy, as always in need of a summer job, returned to Pennsylvania to manage the Warren Warriors of the split-season, eight-team, Class-D Interstate League. (He was reportedly Warren’s second choice, after the notorious Hal Chase, who joined the Cincinnati Reds instead.) Six Senators stalwarts, including first baseman Cozy Dolan, shortstop Frank Smykal, and right-hander Louis Peterson, joined Shag in Pennsylvania.74 Someone else could worry about the financial viability of a minor-league baseball team for a change. As it turned out, there would be lots to worry about.

It didn’t take long for Shaughnessy’s “ugly temper”75 to make an appearance. In early June, during a game in Olean, New York, he launched an X-rated tirade at the umpire (hint: It did not include the phrase “grey-headed old loafer”), after which he flung his bat into the crowd. For Shag it marked a reprise of a bat-tossing incident in his days as a Roanoke Tiger. Fortunately for all concerned, no one was injured in either incident, but newspapers in other league cities were not impressed. “We believe there are a large number of good sportsmen in Warren who would blush for shame at the ‘rank stuff’ pulled here by their manager,” the Ridgway Record chastised. “If he tries it again he will be arrested.”76

With a population distracted by preparations for the war in Europe and by an actual war with Mexico, attendance in the Interstate was down by half. On August 3 Warren, some $800 in debt and owing players two weeks’ salary, became the second of three league clubs to fold in less than a month. The Wellsville Reporter speculated that Shaughnessy would return to Canada to raise a company of athletes to fight in the war. Instead Shag signed with the first-place Bradford Drillers, but as a player only. Then, a few weeks later, he moved over to the also-ran Wellsville Rainmakers as playing manager. In an uncertain, no-fixed-address kind of season, Shag still recorded a .301 batting average and stole 19 bases in 76 games. But for the first time since 1911, he failed to win a pennant.

Back home in Ottawa in early September, Shaughnessy set about arranging a pair of exhibition games for Lansdowne Park, pitting future Hall of Famer Tris Speaker and his “All-Americans” barnstorming squad against the “International All-stars,” a team consisting mostly of Montréal Royals and managed by the Royals’ Dan Howley. On October 6 both Shaughnessy and Howley played in the field against the American Leaguers. Shag had a hit off the Detroit Tigers’ Jean Dubuc, but the Internationals lost 6-2.

After a couple of games in Montréal – Shaughnessy played in one of them – the teams returned to Ottawa for a Thanksgiving Monday exhibition game. The game marked a homecoming for prize Senators grad Herbie Shocker, who had split the season between the Yankees of the American League and the Maple Leafs of the International, where he’d gone 15-3 with a 1.31 ERA. Facing the likes of Speaker, the American League batting champ, ill-fated Cleveland shortstop Ray Chapman, and future Black Sox first baseman Chick Gandil, Shocker scattered nine hits and beat eventual 223-game winner George “Hooks” Dauss of the Detroit Tigers, 3-2.

SIBERIA

For Shaughnessy it would not be fall without football. But with collegiate ball on hold for the year, the autumn of 1916 found him coaching the 207th Battalion team to the championship of the military’s Overseas Football League. He also continued as business manager of the hockey Senators, even swinging a deal to pry future Hall of Famer Cy Denneny away from Toronto. But in November Shaughnessy, now 33 and the father of four boys, decided to sign up.

On his Officer’s Declaration form he gave his profession as “attorney and athletic director,”77 and he agreed to be vaccinated. His medical sheet lists him at 6-feet-1½-inches and 195 pounds, with “excellent physical development.”78 Said the Citizen: “Frank has worn baseball and football togs for so many years that he had no difficulty in adapting himself to the King’s uniform.”79

At first Shaughnessy’s military career was not all that different from his civilian one. He coached and played baseball, coached football and even coached hockey. (“… Frank’s advice is invariably brief, but to the point, viz: ‘Get the goals and then lay back on the defense.’”)80 But Shaughnessy’s real value to the military was his extensive web of contacts in the sporting world. After all, who better to take on the Hun than an army of elite young athletes? He was soon placed in charge of recruiting in Ottawa for the 207th Battalion, and in typical Shag style he out-recruited all the other recruiters. “In his short-term as re-inforcing officer, Lieut. Shaughnessy established a record for recruiting as he secured over a hundred men.”81 “Before the current call is exhausted … the Capital will be without ninety per cent of its leading athletes, and unless the war ends shortly, it will be difficult for the various local clubs to carry on successfully,” said the Citizen. “The list of Ottawa athletes who have given up their lives for the Empire is a glorious one and, apparently, the majority of those now rallying to the colors are eager to sign up, that they may perpetuate the glory of those who have gone before them.”82 Dulce et decorum est.

Shag spent part of 1918 in a familiar working environment. In early summer his battery was quartered at Lansdowne Park, a fairly short walk from his home in Ottawa’s Glebe neighborhood. Summer evenings his men played baseball. In September 1918 Shaughnessy transferred to the Ammunition Column, 35th Battery, Canadian Expeditionary Force (Siberia). The big show in Europe had only a few weeks left to run, but Canada was still involved in – and in command of – a confused and half-hearted Allied campaign to support the White Russian Army against the Bolsheviks in Russia’s Far East. Shag had experienced a number of baseball Siberias during his career, but never before the real thing. And now, at the peak of the Spanish flu pandemic, he found himself in New Westminster, British Columbia, preparing to embark on a slow boat to Vladivostok.

On November 28, 17 days after the war ended on the Western Front, Shag and his mates finally sailed from Vancouver on the “remount ship” S.S. War Charger. They carried a cargo of 500 or 600 horses – half of them on deck – and a load of 16- and 18-pound artillery shells below. “I think they picked me because I was as big as a horse,” Shag said.83 They wallowed 500 miles in 23 days until, in danger of running out of coal, they were ordered to turn back. The ship docked in Vancouver on December 4, no doubt to the widespread relief of most of its passengers. “The funniest thing that happened to me was that I was sentenced to Siberia – and never got there,” said Shag.84 On January 21, 1919, Lieut. Frank Shaughnessy left the army by “reason of General Demobilization”85 and returned home to Ottawa.

THE INTERNATIONAL

Shaughnessy resumed his McGill position, which had expanded to include responsibility for all outdoor sports at the university. But, as always, he would need a baseball gig to see him through the summer. “I worked hard because I liked it,” he said, “and if I needed a better reason, I had a big family and had something of a grocery bill every week.”86

Shag pursued a number of leads, including the possible formation of an all-Canadian league that would incorporate the Ontario clubs from the Michigan-Ontario League, along with Ottawa and Montréal. “If the new league is formed, I will take either the Montréal or Ottawa franchises, or at least will take a financial interest in them…,” he said. “There is no doubt in my mind that an all-Canadian league would be a howling success.”87 But his fellow magnates did not share his conviction, and the league he envisioned failed to get off the ground.

There was also talk of relocating an International League franchise to Ottawa. But nothing panned out on that front either. Shaughnessy, with considerable reluctance, accepted an offer to play for and manage the Hamilton Tigers of the Class-B Michigan-Ontario League. Now 36 and returning after a two-season layoff, Shag nonetheless put up one of the best offensive seasons of his long career, batting .313 with a .412 on-base percentage in 109 games. But his Tigers, featuring several former Senators, came up just short. They finished second, three games back of the Saginaw Aces.88

Shaughnessy seemed to be growing weary of the peripatetic baseball life and the burdens of leadership. In August he went as far as announcing his intention to retire as both player and manager at season’s end. “Managing a baseball team is far from being what it may seem to the average fan in the bleachers,” he told the Citizen. “The player who has nothing to do but play his position each game, and whose worries end with the game each day, has an easy time; but the manager has just as many worries off the field as on. I will make a desperate effort to win the pennant this year, but win or lose I am not going to attempt to fill the role of manager any more.”89

And yet in the fall of 1919 Shaughnessy was rumored to have the inside track on replacing Canadian Baseball Hall of Famer George “Mooney” Gibson as manager of the Toronto Maple Leafs. That didn’t happen either. And so, in 1920, he returned to Hamilton as player-manager of the Tigers. His team again finished second, this time 14½ games behind the runaway London Tecumsehs. It was the same old fiery Frank, though. In late May he was arrested for getting into a fight in Flint. His offensive production, however, declined dramatically – a .262 batting average with 16 stolen bases in 93 games. It was his swan song as a regular or semi-regular player.

During the 1920-21 offseason, Shaughnessy continued his struggle to bring high-level baseball back to either Ottawa or Montréal. There was talk of Shag and Knotty Lee acquiring the Syracuse or Akron franchise in the International League and moving it north of the border. There were also reports of the pair trying to add some Canadian content to the New York State League. If they landed a baseball franchise for Ottawa, Shag and his rapidly expanding family – seventh son Peter would be born in 1921 – would stay put. In the event of a team for Montréal, he would relocate his family there. But in the end the Shaughnessy-Lee duo could not make a business case for either city.

A BRISK NORTH WIND

In 1921 the Shaughnessys decamped with their seven boys to Montréal, with the half-baked idea of Frank selling insurance to supplement his McGill income. The Shaughnessy era in Ottawa was over.

Predictably, Shag’s insurance career lasted about as long as his half-hearted attempt to practice law in Roanoke. “In fact,” The Sporting News noted, “every time Shag decided to ‘settle down,’ baseball sounded a recall.”90 In midseason 1921 he took over as manager of the chronically second-division Syracuse Stars of the International League. It was a position he would hold until the 1925 season, when he was fired after a 9-28 start. More significantly the Syracuse gig marked the beginning of a 40-year relationship with the circuit.

In 1932 Charles Trudeau and his partners hired Shaughnessy as general manager of the Montréal Royals. While with the Royals, Shag successfully pushed for what came to be known as the Shaughnessy playoff system, a postseason series widely credited with saving minor-league baseball from extinction during the Depression. In 1936 he was appointed president of the International, and for the next 24 years he served as a passionate defender of the interests of minorleague baseball. Said the New York Times: “He’s as big as all outdoors and as hearty as a brisk north wind.”91

Among the highlights of his tenure was the Royals’ 1945 signing of Jackie Robinson. Shaughnessy, caught flatfooted by the historic breakthrough, nevertheless endorsed integration “as long as any fellow’s the right type and can make good and can get along with other players.”92 As for Robinson being that fellow, Shag professed no doubts: “He’s the best player in minor league ball. He’s also the smartest.”93 We might wonder whether during this time Shaughnessy ever thought of his old Northern League opponent, William Matthews, and the four decades of racial hypocrisy since he had been touted as a sure-fire major-league talent.

Shag finally retired in 1960, at the age of 77. Over his career, which spanned more than half a century, he had established himself as one of the most influential personalities in baseball – or, as Montréal sportswriter Tim Burke said, “one of the most extraordinary figures in the history of sport.”94

Kitty Shaughnessy, whose homesickness led to the creation of the Ottawa Senators, died in 1958 in Montréal, a week after the Shaughnessys’ 50th wedding anniversary. Frank died on May 15, 1969, also in Montréal, at the age of 86. He was among the first inductees into the Canadian Baseball Hall of Fame, in 1983.

“I remember him as kind and big and gruff,” his granddaughter Honora Shaughnessy told me. “He would always have a TV and one or two portable radios going at the same time, listening to various games. I remember my father always called him ‘Sir.’”95

DAVID McDONALD is a writer, broadcaster, and filmmaker, with a particular interest in the long and colorful history of baseball in Ottawa, where he lives.

Notes

1 Joe King and Cy Kritzer, “Shaughnessy,” The Sporting News, December 14, 1960: 16.

2 After two unrelated Shaughnessys who preceded him to Notre Dame, both nicknamed “Shag.”

3 An “outlaw,” or independent, league is one that is not part of the National Agreement and therefore beyond the jurisdiction of Organized Baseball.

4 Not to be confused with another circuit called the Northern League, which operated in Manitoba, North Dakota, and Minnesota during this period.

5 Joe King and Cy Kritzer, “Diamond Ace, Gridiron Star and Executive,” The Sporting News, December 14, 1960: 10.

6 From “The Man Has Better Things to Do Than Talk About Himself,” unattributed 1968 newspaper clipping. Courtesy Honora Shaughnessy.

7 He was the starting right end on the undefeated 1903 team that outscored its opponents 291-0 over nine games.

8 David Pietrusza, Minor Miracles: The Legend and Lure of Minor League Baseball (Lanham, Maryland: Taylor Trade Publishing, 1995), 119.

9 Soon to be a two-team league, as Montpelier-Barre and Burlington were the only teams to survive the season.

10 Quinn was the proprietor of Revere House, 475-479 Sussex Drive, Ottawa, until selling out in 1912.

11 “Notes of Sport,” Ottawa Journal, July 13, 1906: 2.

12 “Greens Take One of the Doubleheader,” Wheeling News Register, September 2, 1906: 6.

13 Jerry Kuntz, Baseball Fiends and Flying Machines: The Many Lives and Outrageous Times of George and Alfred Lawson, (Jefferson, North Carolina: McFarland Publishing, 2009), 126.

14 Pietrusza, 120.

15 Pietrusza, 120.

16 The dealership sold – or at least attempted to sell – the Virginian, a short-lived make built in Richmond.

17 Frederick Edwards, “Old-Fashioned Father,” Maclean’s, October 1, 1934: 15.

18 “‘Home Run’ Shaughnessy Pays Ottawa a Visit,” unattributed 1910 newspaper clipping. Courtesy Honora Shaughnessy.

19 Ahearn became part-owner of the hockey Senators, 1920/21-1933/34. He was selected to the Hockey Hall of Fame as a builder in 1962.

20 “News Notes,” Sporting Life, February 24, 1912: 15.

21 “Arranging for Sunday Baseball Games,” Ottawa Journal, April 2, 1912: 9.

22 “No Sunday Ball to Be Played Here in Canadian League,” Ottawa Citizen, April 23, 1912: 8.

23 “Ottawa Ball Club Sign Up a Star Catcher,” Ottawa Journal, March 2, 1912: 5.

24 “Ottawa’s Now Certain of Draper, Deal Was Closed Yesterday,” Ottawa Citizen, April 2, 1912: 8.

25 Ottawa Journal, April 15, 1912: 1.

26 “Rousing Reception Now Assured for Members of Ottawa Ball Club,” Ottawa Citizen, May 9, 1912: 8.

27 “Expect McManus to Recover Quickly,” Ottawa Journal, July 26, 1912: 5.

28 “Canadian League Pennant Comes to Ottawa, Senators Took Doubleheader from London,” Ottawa Citizen, August 19, 1912: 8.

29 “Watch the Race,” Ottawa Journal, September 4, 1912: 4.

30 Telegram from Frank to Kitty Shaughnessy, September 2, 1912. Courtesy Honora Shaughnessy.

31 “Ottawa Baseball Team Disbands, Kind Words for Local Friends,” Ottawa Citizen, September 4, 1912: 8.

32 “Ottawa Didn’t Play Yesterday, All Games Off Because of Rain,” Ottawa Citizen, August 20, 1912: 9.

33 The oldest active football trophy in North America, dating back to 1898.

34 “He is credited with having more to do with changing Canadian football, by introduction of American football tactics, than any other man.” King and Kritzer, “Shaughnessy.” “It was largely through his campaigning that the Canadian game adopted the forward pass, 12-man teams and the direct snap from center. …” Marven Moss, “Frank ‘Shag’ Shaughnessy Is Still Rolling in High Gear Despite His Age, Leading Battle for Minor Clubs,” Sherbrooke Daily Record, January 11, 1958: 8.

35 King and Kritzer, “Shaughnessy.”

36 “Ottawas Get Frank Shaughnessy as Manager for Next Season,” Ottawa Citizen, January 17, 1913: 9.

37 “Ottawa and Brantford Teams Open Local Season Month from Today,” Ottawa Citizen, April 15, 1913: 8. The Senators lost three key players to higher classifications in the 1912 draft: shortstop Artie Schwind (Boston Braves) and pitchers Fred Herbert and Frank Kubat (Toronto Maple Leafs).

38 “George A. Kempf Dead,” Chicago Inter Ocean, 16 April 16, 1913:14.

39 “Ottawa and Brantford Teams Open Local Season Month from Today,” Ottawa Citizen, Apr. 24, 1913: 8.

40 Later in 1913, Shaughnessy, as he had done in Roanoke, bought into an Ottawa automobile dealership.

41 “Great Pitching Duel Expected at Lansdowne Park Today,” Ottawa Citizen, May 17, 1913: 8.

42“Darkness Ended Thrilling Game, Ottawa & St. Thomas Play Tie 1-1,” Ottawa Citizen, May 21, 1913: 8.

43 “Shaughnessy Hailed to Court at St. Thomas,” Ottawa Citizen, July 9, 1913: 8.

44 “Shaughnessy Hailed to Court at St. Thomas.”

45 “Shaughnessy May Become Big League Manager,” Ottawa Citizen, August 12, 1915: 8.

46 “‘Shag’ Deserves Credit,” Hamilton Herald, August 29, 1914: 9.

47 Bert Perry, “Looks Like Fourth Straight Pennant for Ottawa Club,” London Advertiser, August 4, 1915: 8.

48 Bill Rhodes, London Free Press, undated 1915 clipping. Courtesy Honora Shaughnessy.

49 Renfer finished with 21 wins and was drafted by the Detroit Tigers in the fall of 1913. After a four-week layoff, he started – and lost – a game against the Washington Senators. That was the extent of his major-league career.

50 Deneau was born in Amherstburg, Ontario, in 1879, and played 10 years in the minors.

51 Ottawa, at 66-39, finished .008 ahead of London, 64-39.

52 In the offseason Dolan served as trainer of whatever football or hockey club Shaughnessy happened to be coaching at the time.

53 Alan Metcalfe, Canada Learns to Play: The Emergence of Organized Sport in Canada, 1807-1914 (Toronto: McClelland and Stewart, 1987).

54 “Toronto Broke Ottawa’s Winning Streak in First Game of Canadian League Season, Bullock’s Error Paved Way for Defeat,” Ottawa Citizen, May 15, 1914: 8.

55 “Ottawa and London Baseball Clubs Summoned for Sunday Ball in Hull,” Ottawa Citizen, August 10, 1914: 1.

56 Ottawa Citizen, June 29, 1914: 12.

57 Reisling and Shaughnessy had both played for Coatesville/Shamokin in the Tri-State League in 1905.

58 “Ottawas Have Chance to Make Fresh Start Against St. Thomas Team This Afternoon,” Ottawa Citizen, July 16, 1914: 8.

59 Mitchell (born Kmieciak) would be called Johnny Mitchell during a five-year major-league career, 1921-25.

60 “Champs. Caught London after Stern Chase of 57 Days,” unattributed newspaper clipping, 1914. Courtesy Honora Shaughnessy.

61 Shocker would be the last legal spitballer on the Yankees after the pitch was outlawed in 1920. In 1921 he tied for the major-league lead in wins with 27. He died in September 1928, two weeks shy of his 38th birthday.

62 “Ottawas Scored 8 Runs in Two Innings and Easily Disposed of Brantford; Del Chase No Puzzle for Senators,” Ottawa Citizen, August 19, 1914: 8.

63 “‘Shag’ Deserves Credit: Hamilton Papers Comment on Baseball Struggle,” Ottawa Citizen, August 29, 1914: 9.

64 Tripleheaders in Organized Baseball were extremely rare, but not unprecedented. By this time there had already been two at the major-league level. On September 1, 1890, the Brooklyn Bridegrooms beat the Pittsburgh Alleghenies three times on their way to the NL title. On September 7, 1896, the pennant-bound Baltimore Orioles swept a Labor Day tripleheader from the Louisville Colonels.

65 “Canadian Ball League Pennant Comes to Ottawa; Champions Downed Peterboro and Won Flag Again,” Ottawa Citizen, September 8, 1914: 8.

66 London Advertiser, September 8, 1914: 7.

67 “London Downs Saints Three Times but Loses Pennant,” London Free Press, September 8, 1914.

68 “Probably the Cold Was in Shaughnessy’s Feet,” London Advertiser, September 8, 1914: 7.

69 Unattributed clipping from summer 1915. Courtesy Honora Shaughnessy.

70 M.H. Sexton, “By the Editor of ‘Sporting Life’,” Sporting Life, December 12, 1914: 13.

71 J. Harry Fowler, “The Canadian League,” Sporting Life, November 21, 1914: 19.

72 “Hard to Prove Ottawa Broke Limits,” Ottawa Citizen, September 22, 1915: 9.

73 “Baseball Men Making Ready for Opening,” Ottawa Citizen, April 3, 1916: 7.

74 Contemporary Ottawa newspapers all spelled Peterson’s first name as Louis.

75 “Olean Beat Warren,” Jamestown (New York) Journal, June 7, 1916: 14.

76 “League Notes,” Jamestown Journal, June 8, 1916: 14.

77 Officers’ Declaration Paper, Canadian Over-Seas Expeditionary Force, December 22, 1916.

78 Medical History Sheet, February 17, 1917.

79 “Shag in New Role,” Ottawa Citizen, December 21, 1916: 8.

80 “Shag in New Role.”

81 “Ottawa Athletes to Kingston School,” Ottawa Citizen, January 15, 1917: 8.

82 “Many More Ottawa Athletes Called in First Draft under New Military Service Law,” Ottawa Citizen, May 6, 1918: 8.

83 John Kieran, “Under Two Flags,” New York Times, January 23, 1941: 27.

84 Kieran.

85 Canadian Expeditionary Force Certificate of Service, March 4, 1920.

86Joe King and Cy Kritzer, “Shag, as a Farm Manager, Polished Rickey’s Kid Stars,” The Sporting News, December 14, 1960: 26.

87 “Shaughnessy Is Planning for New Baseball League,” Ottawa Citizen, August 4, 1919: 8.

88 Some sources say the team finished 3½ games back.

89 “Shaughnessy Is Planning for New Baseball League.”

90 King and Kritzer, “Shag, as a Farm Manager, Polished Rickey’s Kid Stars.”

91 Kieran.

92 “Montréal Signing Negro Ace a Headache for Chandler,” Bergen (New Jersey) Record, October 24, 1945: 19.

93 Sam Blackman, Tim Bourret, and Dabo Swinney, If These Walls Could Talk: Stories from the Clemson Tigers Sideline, Locker Room, and Press Box (Chicago: Triumph Books, 2016).

94 Tim Burke, “Shaughnessy Clan Full of Rich History,” Montréal Gazette, June 15, 1982: B-5.

95 Honora Shaughnessy, telephone interview with author, August 6, 2002.