Fred Corcoran, Mr. Golf’s Turn at Bat

This article was written by John H. Schwarz

This article was published in Spring 2021 Baseball Research Journal

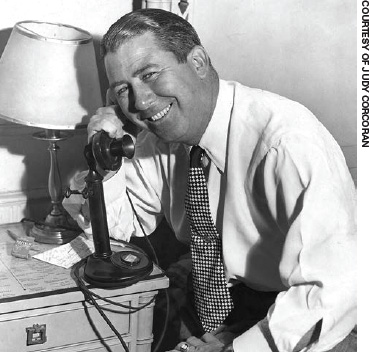

Although he was known as “Mr. Golf,” Fred Corcoran served as agent to Ted Williams and other players. For a time, he and Frank Scott were the only agents working with baseball players. (COURTESY OF JUDY CORCORAN)

Fred Corcoran was the go-to guy in golf circles, starting in the late 1930s. He had successfully helped promote and sustain the fledgling PGA tour and not only had applied his business acumen to the game but had also helped guide the career of the incomparable Sam Snead. Already one of golf’s greatest players, Snead had become, with Corcoran’s help, one of the most sought-after golf celebrities of the 1940s.

But Corcoran’s sports knowledge and internal Rolodex went way beyond professional golf and golfers. During World War II, he took former boxing champion Jack Sharkey and New York Yankees pitcher Lefty Gomez on a tour of US Army bases in England and Italy. There he conducted a combination pep talk and sports nostalgia discussion to help raise the morale of the troops and bring them a part of American life that most GIs easily and fondly related to.

Known as “Mr. Golf,” Corcoran befriended almost everybody who was anybody in sports and entertainment. Among his friends were Bing Crosby, Bob Hope, Johnny Weissmuller, Jim Thorpe, Walter Hagen, Babe Ruth, and Ty Cobb, as well as most members of the sports press. His ties to most of these people came from the emerging popularity of golf, his engaging personality and encyclopedic recall of sports statistics, and some of the promotions he directed. But Corcoran’s influence in the sports world broadened into the game of baseball when he met Ted Williams in 1946.

Life was a lot more casual in the late forties and Williams, a fixture on the Boston sports scene, was much more of a “regular” person in his daily life than the sports superstars of today. He lived in the heart of the community and he had to take care of his basic needs just like everyone else did. When he needed to buy a car, Ted ended up favoring a car dealership in Wellesley, Massachusetts, that sold Fords. The manager of the dealership was John Corcoran, Fred’s brother. The Corcoran boys had grown up in Cambridge and all got their start in golf as caddies at the Belmont Golf Club.

Stopping at the dealership to see John one day, Williams complained bitterly about all the demands people put on his time and the distractions it created from his main focus—hitting a baseball. As he put it in his inimitable Ted Williams style, “These goddam guys won’t leave me alone and I don’t want them bothering me. I’d like somebody who could deal with these sons of bitches and get ’em off my back.”1

In the mid-forties, athletes were pretty much on their own. Ted had an accountant/business manager named James Silin, whom he later replaced with Corcoran, but no one before Corcoran proactively thought about how to capitalize on the demand for Williams’s charisma.2 Negotiating player contracts before 1975, when the renewal clause was limited to one year, was pretty much a one-way street. The team made you an offer; if you didn’t like it you could bellyache, but in the end, you signed the deal and got paid, or you didn’t sign, held out as long as you could, and didn’t get paid. But for a select few, like Williams, their stardom surpassed the baseball diamond and led to potential value from their name and face off the field.

John Corcoran suggested to Williams that he meet his brother. Fred was handling a lot of these “distractions” for Snead and others in the golf world, and Corcoran knew everyone and everything that was going on in the sports world. It would be a perfect marriage. Williams was game, maybe even desperate at the time, and a meeting was arranged.

Corcoran and Williams hit it off right away. Corcoran had clout in his field that matched that of Williams on the baseball field. To solidify their arrangement, Corcoran suggested a short letter of agreement, but Williams preferred just a handshake. As was proven later in his life when his son blatantly took advantage of his father, Williams could be too trusting. But in 1946, it was a good thing he was dealing with Corco- ran, who did get a short agreement typed up. The conversation around their first agreement went something like this:

“I’ll take fifteen percent,” Corcoran said.

“Fifty, okay,” Williams replied.

“No, not fifty,” Corcoran corrected him, “Fifteen.”

“Whatever you say. If you want to make it fifty, it is all right with me,” responded Williams.

“I assure you that fifteen percent is a generous working margin,” repeated Corcoran.3

The two shook on it, and when the understanding came up for renewal, Williams insisted on giving Corcoran a raise and memorialized the deal in Williams fashion. He provided a letter to Fred outlining the terms and signed by each. It was a simple note which read as follows and was signed by both men:

Dear Fred:

This will confirm that we extend our agreement of management made in 1946 which was for a five year period for an additional period of five years for the same terms and conditions except you are to receive 30 percent.

— Theodore S. Williams

Agreed Fred Corcoran

A far cry from a player-agent contract in today’s world.

At the time Williams forged this relationship with Corcoran, there was very little history of baseball players or any sports figure employing an agent. When Red Grange decided to play pro football in the twenties, he did employ an agent named Charles “CC” Pyle (CC appropriately stood for Cash and Carry), and later Babe Ruth and several other baseball greats used Christy Walsh, a super promoter, to garner them some additional money using their names and/or appearances. Walsh’s specialty was employing professional writers to author newspaper columns under the name of the star. Most of the articles were ghostwritten to present a “you were there” kind of column as though the player were taking you into his thoughts on the events. Walsh served as both a PR agent and a financial advisor for Ruth, which did create a model for later agents, but following his representation of Ruth and others including many non-baseball celebrities, there was a long hiatus before the modern agent as represented by Corcoran’s relationship with Williams developed.4

Frank Scott, another agent, began helping baseball players shortly after Corcoran began working for Williams. Many baseball historians have incorrectly assigned Scott the role of first player agent. While Scott expanded his roster to a far greater number of ballplayers than Corcoran (who still had golf responsibilities), his representation was based on Corcoran’s model with Williams. Scott was a traveling secretary for the Yankees, but was fired when he sided with the players over management when it came to spying on their road goings-on. From a friendship with Yogi Berra, Scott realized both what a distraction various side requests were to players and how they were often rewarded for their time with only token gifts.5 His early work with Yankee greats began in 1950, four years after Corcoran and Williams were together.

Corcoran, who was the first non-player enshrined in the World Golf Hall of Fame, didn’t receive his due in some circles. When you ask, “Who was the first person to represent golfers?” the answer 99% of the time is Mark McCormick. And when you ask about baseball, if anyone hazards a guess at all, they name Scott. In reality, Corcoran preceded both.

Prior to meeting Williams, Corcoran’s main connection to baseball was his friendships with the retired Ty Cobb and Babe Ruth. In his quest to shine a brighter light on golf, Corcoran staged some fun promotional events at baseball and football fields. In fact, Corcoran’s introduction to Ruth came as a result of a promotion with Snead. The golfer dazzled the crowd at Wrigley Field when he teed off from home plate and bounced golf balls off a new Cubs scoreboard some four hundred plus feet away—something no major league batsman could do. Ruth had tried to get to Wrigley Field to observe the great Snead’s performance, but plane connections didn’t work out. However, the Babe tracked down Snead and Corcoran postgame in a bar and a lifelong friendship was born.6 Cobb was another avid post-career golfer who had met Mr. Golf along the way.

In the early forties, Fred convinced Ruth and Cobb to settle their baseball rivalry on the golf course. Both loved the game of golf and fancied themselves as good players. At the time, Cobb was 54 years old and Ruth was 46. Both highly competitive and often combative, Ruth and Cobb deeply respected one another, even though their competitiveness around who was the best baseball player of all time was always in play. Corcoran figured out how to work the players’ egos to bring them together on the golf course and raise money for charity in the process. The publicity didn’t hurt, either.

It took a lot of massaging Cobb to finally get him to agree to a match. Cobb did not want to lose and wasn’t sure this event would be a slam dunk for him. Ruth seemed more self-confident and probably was considered an underdog in this sport, making it a major accomplishment to win and more defensible if he lost. Corcoran worked on Cobb and ultimately convinced him to take the challenge. Judy Corcoran, Fred’s daughter, wrote this about the match in her book, The Has Beens Cup.

“I’ll beat him because I care more,” Cobb sneered. “But I’d probably have to get him upset. That’s how I’d beat him. I’d just get his goat.” Cobb believed to beat any opponent was to irritate, embarrass, dare, distract and bully him into losing his composure.

“I bet you would win,” Fred said.

The final trick to get Cobb to say yes came about when Corcoran reminded Cobb of a note Fred had received from the Babe. The note said, “I can beat Cobb any day of the week and twice on Sunday at the Scottish game.”

Cobb, in finally accepting the match, wrote to Ruth, “I could always lick you on a ball field and I can lick you on a golf course.”7

The event was named, “The Greatest Championship Golf Match of All Time”—a bit of hyperbole. Ruth called it, “The Left-Handed Has-Beens Golf Championship of Nowhere in Particular.”

The first of the three matches between the two was played on June 25, 1941, in Newton, Massachusetts. Cobb won 3 and 2. The second match was played two days later on June 27 at Fresh Meadow in Queens, New York, where Ruth prevailed on the 19th hole 1 up. A final rubber match was played on July 29, 1941, in Detroit at the Grosse Ile Golf Club. Cobb prevailed 3 and 2 to take the series. Cobb said later that the event was one of the highlights of his life and it was later reported that he kept two things on his mantle—his Baseball Hall of Fame plaque and the Has-Beens trophy. Cobb and Corcoran also became life-long friends.

For several years, Scott and Corcoran were the only professional agents dealing with baseball players. While Tom Yawkey and Joe Cronin offered Corcoran the job of traveling secretary for the Boston Red Sox, he turned it down. He was Mr. Golf and baseball was a side business. At first Yawkey and Cronin were very suspicious of Corcoran’s relationship with Williams, but once they decided it was not a threat to his base-ball activities and maybe even made his baseball commitment stronger, they condoned the arrangement. Later, Corcoran did broaden his base to other special players: St. Louis’s Stan Musial and Boston’s Tony Conigliaro.

With the end of the Second World War, Corcoran wasted no time in landing off-field deals for Williams in 1946. His first call was to L.B. Icely at the Wilson Sporting Goods Company, suggested Williams for the company’s advisory staff. The result was an immediate contract with a $30,000 guarantee, three percent on all sales, and a ten-year deal. Williams was off and running.

Many of Corcoran’s early efforts with Williams tried to make him understand how important it was for him to stop scrapping with the press, and especially with the fans. Image was the lifeblood of his attractiveness to sponsors, and Williams seemed to be doing everything he could to present the wrong one. Corcoran did not always have a great deal of success in modifying Williams’s behavior, but he inserted himself often as the buffer between Williams and others. Cobb, who knew and liked Williams, gave Corcoran the following advice:

Ted is like an outlaw horse that has certain fine ability but tears and pitches in the harness of society and gets many burns and wounds. But that means nothing to him. He retires quickly to those who fawn upon him. Neither you nor I nor anyone else with the interest or desire to help Ted can ever accomplish one thing for him…so it’s better to endure him and save one’s self.8

With Williams and Cobb always in his corner, Corcoran was best friends of two of the orneriest men in baseball. That certainly says something about the man himself. Perhaps Corcoran understood Williams and how his quick temper was a result of a difficult childhood and a distrust that had built up through his formative years. He also knew Williams as one of the most honest and kind people when one got to know him and that he was an extremely loyal friend. It was no accident that the bond developed among the Red Sox core players of that era was anchored by Williams. David Halberstam’s book, The Teammates, explores this relationship and highlights how Williams fit in among his friends and peers on the team.

Off the field, Williams was an intensely private person, which led to his obsession with fishing, hunting, and the outdoors where he could be peacefully alone and away from the world. Corcoran picked up on how this obsession, when mixed with Williams’s baseball fame, could turn into a good commercial opportunity. The actual reward in this area came almost by accident. Corcoran, like a good front man, spent a lot of time where he thought there might be action. In 1950, on a night when he returned from a golf event in the Midwest, he decided to kill some time in New York at Toots Shor’s restaurant.

That night, with the Sportsman’s Show in New York, he met up with friends from the Bristol Company. They manufactured golf club shafts, but also made fishing rods. Thanks to a chance conversation that night, Corcoran landed a 10-year, $100,000 contract for Williams to endorse Bristol’s Horton fishing equipment. It was a perfect fit. Corcoran was making Williams wealthier, and doing it in ways that Williams could shine.

The economic partnership between Williams and Corcoran had its apex during Williams’s playing days. As Williams reached retirement, the relationship began to transition into more of a strong personal friendship. The day after Williams officially retired from the Red Sox in 1960, he signed a deal with Sears Roebuck to head up the Sears Sports Advisory Staff. It made him an employee of Sears, and paid $125,000 per year plus a percentage of sales on all “Ted Williams” equipment sold. It also catapulted him into a position of the country’s most visible expert on fishing and fishing equipment.

Through Corcoran, Williams had become a close friend of Snead. The golfer and ballplayer had founded a company called Ted Williams Tackle, Inc. that made and sold fishing flies. As part of the Sears deal, that company eventually got swept into Sears’s product line.9

Prior to Williams settling in with Sears Roebuck, Corcoran got in the middle of another opportunity for Williams to stay in baseball. Dan Topping, the owner of the Yankees, came to Corcoran to see if Williams would be interested in joining the Yankees for the 1961 season just as a pinch hitter. Topping was willing to pay Williams $125,000 for the season. It was certainly a fair offer, but Corcoran told Topping that before he could consider it, the Yankees needed to talk to Yawkey. The Red Sox owner was still paying Williams. Topping refused to get into negotiations with Yawkey, so the offer fizzled. For the long term, Williams having landed with Sears was the right next step.

With Williams happily and safely tucked away under the Sears umbrella and not making on-field headlines any more, the need for Corcoran’s services diminished. Williams, however, remained a loyal friend. Still associated with the Red Sox, Williams spent every spring at the Red Sox training camp helping young players. One day following the 1965 season, he called Corcoran and told him about a young player named Tony Conigliaro who, at the age of 20, had just completed his second year in the majors and had hit 32 home runs that season. “I think you should sign him,” Williams said as he arranged the meeting.10 Conigliaro had a similar handshake deal with Corcoran as Williams once had. Corcroan immediately called his old friend Sy Berger at Topps Bubble Gum and signed Conigliaro to his first baseball card contract.

Conigliaro might have been a right-handed Ted Williams for the Red Sox had his career not been derailed in 1967 when he was struck in the face by a pitch from California Angels right-handed pitcher Jack Hamilton. With his eyesight affected, Conigliaro never fully recovered. Batting helmets now have a protective ear-flap, partly due to this incident.

Williams did return to baseball as a manager for the expansion Washington Senators 1969—72, a period that included the team’s move to Texas to become the Rangers. Williams was tough on the players and very dogmatic in his theories of the game. His managerial record was below .500. He was much more at home in his post-baseball days hiding out in Florida and spending lots of time with fishing buddies.

The relationship between Corcoran and Williams during the latter’s playing career ran deeper than just endorsements and side money. Corcoran honed Williams’s image as best he could, given Williams’s natural tendency to be quick-tempered and aloof. A classic example of Corcoran’s influence came when Williams was recalled into the Marine Corps in 1952, right in the prime of his playing career. Most people today think of Williams’s time in the Corps as the epitome of public service selflessly performed by a true patriot. That was not exactly how it started out, but thanks partly to Corcoran, that is how it has come to be viewed.

When Williams first received the call-back to service, he was livid. He was convinced that he was singled out because of his high baseball profile. There were plenty of worthy pilots who could perform those tasks who weren’t in the prime of a baseball career and, furthermore, he had been away from flying for long enough to virtually require re-education on the updated equipment. Because Williams wasn’t shy, his natural tendency would have been to make a stink even if it were to be of no avail. Corcoran caught him in time, calmed him down, and convinced him he needed to treat the inevitable as though he was in control. He realized his importance to his country and he would do his duty as any concerned American would. The choice was being a bitter spoiled baseball player or a super-hero patriot. Corcoran knew the right choice and he helped Williams find it.

Corcoran’s assistance didn’t just come by way of fatherly advice. While Williams was on duty in Korea, he was still being paid by the Red Sox. Corcoran was responsible for watching over those funds. By investing most of them in a company called IBM, Corcoran did quite well for Williams while he was off flying fighter jets.

And Corcoran was instrumental in getting Williams back into baseball after his tour in Korea. By July 1953, Corcoran got word that Williams was coming home, and as soon as he landed in San Francisco, Corcoran got a call from Ford Frick, the Commissioner of Baseball. Frick was calling to see if Williams could fly to Cincinnati to throw out the first pitch at the All-Star Game. Here’s an excerpt of the ensuing conversation as reported by Judy Corcoran, Fred’s daughter, in Fred Corcoran: The Man Who Sold the World on Golf.

“Everyone wants you at that game,” Fred said, “and they want to see you play. You need to get back to Boston.”

“Hell, no,” Williams said. “I’m out of shape, tired and I’m not feeling well.”

“But there’s still two months left in the season. Everybody wants you back. I think you ought to try to play this year,” Fred pleaded.

“It’s the middle of July, already, Fred. The Red Sox aren’t going anywhere. I’m not ready to play baseball and Mr. Yawkey says I can do what I feel like doing. I feel like fishing. I’m going fishing.”

“But you’re not a fisherman,” Fred protested. “You’re a ballplayer.”

“You’ve never seen me handle a fly rod. I’m the best there is.”

“I’m serious, Ted,” Fred said. “You’ve got to get started. It’ll be the best thing in the world for you. Work yourself in gradually, then be ready for a full season next year. Listen to me—baseball is your business.”

Fred finally got through to him because Ted agreed to go to Cincinnati where the fans at the All-Star Game gave him one of the warmest receptions he ever got—not a boo in the crowd, and that perked him up some more. And during the second half of 1953, in this shortened season with only 37 games, Ted batted .407.11

It was that summer, too, when Williams practiced batting so much to get back in shape that he often got blisters all over his hands. Corcoran happened to be with him on one of these days and gallantly pulled out a golf glove from his bag and suggested Williams wear it while in the batting cage. Williams did and as people around the league saw him wearing it during practice, they started wearing golf gloves. It’s sometimes acknowledged that this is how the batting glove was introduced to baseball. There are some, however, who think the batting glove was used earlier. Peter Morris in his book A Game of Inches suggests that Hughie Jennings may have used batting gloves as early as 1902, and that Lefty O’Doul and Johnny Frederick used them in 1932, as well as Bobby Thomson in the fifties. Hawk Harrelson, who was also a first-class golfer, is credited by many with being the first ballplayer to wear batting gloves in an actual game.12 Regardless, it was no doubt Corcoran who told the press and called attention to it.

From the moment Williams left baseball until Corcoran died in 1977, the two men remained best of friends. Corcoran attended Williams’s induction into the Baseball Hall of Fame and the two men socialized frequently. Williams was considered a member of the Corcoran family. In the sixties, after Williams was out of baseball, he got to know Corcoran’s young daughters through visits to the Corcoran home on the 15th hole of the Winged Foot Golf Club in Mamaroneck, New York.

The young girls developed an apt nickname for “Uncle Ted”—calling him “Old Yeller.” It was the title of a Disney kids’ movie about a dog, but in this case it applied because Williams “was old and a yeller.” He had chastised the girls for brushing their hair after breakfast and before lunch while in the dining room. Long after Corcoran died, Williams kept in contact with his widow Nancy, and was highly appreciative of what the family had done for him.

Corcoran may have lived a baseball fan’s dream in the fifties and early sixties. Not only did he have the opportunity to spend time with the best hitter in the American League, but he also had the same relationship with the best hitter in the National League, Stan Musial.

While Musial and Williams were both great left-handed hitters, they were polar opposites in temperament. Musial was mild-mannered, controlled, and got along with everyone: sportswriters, fans, opponents. He was a perfect fit for a team that played in St. Louis, the heart of the country whose fans hailed from a number of Midwest states. But Musial was a very different sell for Corcoran. Williams may have had a hot temper and easily alienated people, but he had a big-city personality and charisma. He was also John Wayne handsome. Musial was just quiet competence. As Cobb told Corcoran one day: “You manage both Williams and Musial. Why don’t you do more for Musial. Musial is the greatest player in the world, the greatest ballplayer I have ever seen. Ted is a great hitter, but this boy is the greatest all-round player.”13

Corcoran was sympathetic but he was also a realist. In his own book, Unplayable Lies, Corcoran said:

In addition to being a great player, Musial was one of the finest men I ever knew. Yet Musial never moved people like Williams did. Williams had ‘color’ even when striking out. You could walk down the street with Stan and few people paid any attention or even noticed him, but Williams was a star, like Cobb or Snead or Jack Dempsey in this respect. Walk down the street with any of them and taxi drivers would blow their horns and wave.14

In defense of Musial, Corcoran was used to big cities. Were he to walk down the street in St. Louis or Omaha, Nebraska, or Little Rock, Arkansas, Musial would have been “The Man.” Williams may have been big on the coasts but Stan was the guy in the middle of the country. Everyone listened to St. Louis radio on KMOX and everyone who could hear that station with Harry Caray and Joe Garagiola announcing Cardinal games was a Musial fan. But national media didn’t emanate from St. Louis or Omaha or Little Rock.

Corcoran did a lot for Musial during their relationship. However, Musial was by nature a local guy rather than a national figure. The heavyweight stars of the fifties and sixties were Williams, Jackie Robinson, Roger Maris, and Mickey Mantle. The Cardinals had their hey-day in the early forties, and by the time Corcoran arrived for Musial, the team had gone past its peak. The Dodgers, the Yankees, the Red Sox, and later the Braves were drawing national attention. The best player in St. Louis was just that, the best player in St. Louis.

In 1949, Musial became a partner in what became a popular St. Louis restaurant called Stan Musial and Biggie’s. Musial took the restaurant very seriously, showing strong interest in both the food and the business. In 1948, he had moved his family from their off-season home in Donora, Pennsylvania, to St. Louis. Unlike Williams, who ran off to Florida after each season and lived in a hotel while he was in Boston, Musial and his family became full-time members of the St. Louis community. Musial regularly appeared at the restaurant and became close to his business partner, Biggie Garagnani, who also became his mentor. Musial kept an office in the restaurant and hung out there a lot answering his fan mail and learning about the restaurant business and greeting customers.15

Corcoran dealt with Musial’s “baseball stuff,” such as a major deal with St. Louis-based Rawlings Sporting Goods. He also handled things like signing on with the Hartland Company, which successfully made and marketed small plastic statues of sports figures and Western heroes. Those “Hartlands,” as they are called by collectors, are still a big seller on the memorabilia market.

As he did with Williams, Corcoran remained not only an agent but a close friend of Musial. He made sure Musial got his fair share of recognition in sports circles and often accompanied him to events. Musial came out of his shell the night before the All-Star Game in 1960 at Yankee Stadium, and harped to Corcoran on how the managers of All-Star Games should make sure the fans got their fill of the better players (like himself and Ted Williams). He promised he would give the National League fans an idea of what he meant by declaring that if he were put in the game the next day, he would hit a home run. He got in and he did.

When Musial’s career came to an end in 1963, unlike Williams, he was still very committed to baseball and his personality made him a good executive and a perfect ambassador for the Cardinals. At one point he was the team’s General Manager and remained involved with the Cardinal organization almost his full post-playing-career life. He remained in St. Louis until he died in 2013.

Because Corcoran was such a man-about-town, he pretty much knew everybody. As a result, he had other baseball friendships besides the players he represented. One of the strangest was with Moe Berg, the famous catcher/spy whose life has become a favorite of those who love intrigue. Corcoran and Berg actually roomed together for periods of time. More accurately, Corcoran invited Berg to stay with him when Berg seemed to have nowhere else to go. They got along well, but Berg sometimes became dependent on Corcoran and followed him around, maybe even living vicariously through Corcoran’s many friendships and contacts. In 1951, Berg happened to be bunking in with Corcoran when Corcoran proposed to his future wife Nancy. The wedding was a quickly arranged affair with a limited guest list, and Berg was one of those guests. More bizarre, when the Corcorans set off on their honeymoon, which was combined with a golf tournament in Montreal, Berg went along. When Nancy questioned why Berg had been asked to join them, Fred said, “He has nowhere to go and I didn’t want to turn him out.”16

From 1946, when Corcoran first met Williams, until his death in 1977, he remained a name in the world of baseball representation. He was one of the first to show star players how to capitalize on their skills and fan following through off-field endorsements. He not only made those for whom he worked wealthier, but in his worldly wisdom and consummate patience, he helped his clients become better people and understand that their behavior was looked at by others as that of a role model. Admittedly, these are different times today, but many of today’s super agents, the Scott Boras types, could take a lesson from Fred Corcoran. It is about the money but it’s not always about the money.

JOHN H. SCHWARZ is an octogenarian who has been a member of SABR for many years. He started a lifelong love of baseball with the 1945 World Series. He previously wrote for SABR in a piece on Sam “Toothpick” Jones, the first African American to pitch a no-hitter in the major leagues.

Acknowledgments

I’d like to thank Judy Corcoran, daughter of Fred Corcoran, who both helped edit this article and who shared lots of time and stories about her father. Without her help, this story could not have been told with the insight and knowledge that it deserves.

Notes

- Judy Corcoran, Fred Corcoran: The Man Who Sold The World On Golf, New York: Gray Productions, 2010, 101.

- Michael Seidel, Ted Williams: A Baseball Life. Lincoln: University of Nebraska Press, 1991, 118.

- Corcoran, Fred Corcoran, 102.

- Mark Ahrens, “Christy Walsh—Baseball’s First Agent,” Books on Baseball, August 4, 2010, accessed January 27, 2021. https://www.booksonbaseball.com/2010/08/christy-walsh-baseballs-first-agent.

- Deepti Hajela, “Sports Agent Frank Scott Dead At 80,” AP News, June 30, 1998, accessed January 27, 2021. https://apnews.com/e80d981756dba5ab5604f8b69802afce.

- Judy Corcoran, The Has Been Cup, New York: Gray Productions, 2016, 21—25.

- Corcoran, Fred Corcoran, 61—68.

- Corcoran, Fred Corcoran, 114.

- Ben Bradlee, Jr., The Kid: The Immortal Life Of Ted Williams, New York: Little, Brown and Company, 2013, 471—4.

- Corcoran, Fred Corcoran, 211.

- Corcoran, Fred Corcoran, 154—5.

- https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Batting_glove.

- Corcoran, Fred Corcoran, 164.

- Corcoran, Fred Corcoran, 164.

- http://losttables.com/musial/musial.htm.

- Corcoran, Fred Corcoran, 139.