From Bat to Baton: Josh Gibson, the Pittsburgh Opera, and The Summer King

This article was written by David Krell

This article was published in The National Pastime: Steel City Stories (Pittsburgh, 2018)

Josh Gibson was the best player never to play in the major leagues. Perhaps. Such is fodder for debate among baseball historians, scholars, and armchair managers. At 35 years old, Gibson passed away from a brain tumor three months before Jackie Robinson broke the color line with the Brooklyn Dodgers. But Gibson’s life was more than bashing nearly 800 home runs, a statistic celebrated on his plaque at the Baseball Hall of Fame; nobody really knows for sure how many round-trippers the slugger hit because there are no complete accounts of games in the Negro Leagues.

Josh Gibson was the best player never to play in the major leagues. Perhaps. Such is fodder for debate among baseball historians, scholars, and armchair managers. At 35 years old, Gibson passed away from a brain tumor three months before Jackie Robinson broke the color line with the Brooklyn Dodgers. But Gibson’s life was more than bashing nearly 800 home runs, a statistic celebrated on his plaque at the Baseball Hall of Fame; nobody really knows for sure how many round-trippers the slugger hit because there are no complete accounts of games in the Negro Leagues.

While his off-the-field behavior, at times, appeared to be caused by drunkenness, the tumor is the culprit, a fact that went largely unnoticed, as did Gibson’s career, until Negro Leagues scholarship exploded in the 1990s. A member of the Pittsburgh Crawfords and the Homestead Grays, Gibson has enjoyed a renaissance, of sorts. In the 1996 HBO movie Soul of the Game, the icon known as “the black Babe Ruth” gets a just treatment from his portrayer, Mykelti Williamson. Without any gloss, Williamson showcases Gibson’s erratic decorum.

1947 is the setting for “The Unnatural,” an episode of The X-Files that honors Gibson in the final scene. Alien conspiracy investigator Fox Mulder—played by David Duchovny, who also wrote and directed the flashback episode—wears a Grays jersey bearing Gibson’s name while he hits baseballs off a pitching machine at night in the final scene. After leaving a message for his partner, Dana Scully—played by Gillian Anderson and named by the show’s creator, Chris Carter, after Dodgers announcer Vin Scully—to meet “Fox Mantle” at the baseball diamond, Mulder teaches her how to hit a baseball by getting behind her, gripping the bat, and swinging in tandem. Flirtation is evident.

Duchovny, a baseball fan, paid homage to alien and baseball lore by placing the episode in 1947, the year of an alleged UFO landing in Roswell, New Mexico. Mulder and Scully learn of a slugger named Josh Exley, who played for the fictional Roswell Grays. Exley is discovered to be an alien by the original X Files investigator, Arthur Dales, whose brother, also named Arthur, tells the tale to his brother’s successors.

There is also a 2009 documentary highlighting Gibson’s life, The Legend Behind the Plate: The Josh Gibson Story, produced by a dozen Duquesne University students, journalism professor Dennis Woytek, and Pittsburgh television news anchor Mike Clark. While Gibson’s life is celebrated and his death mourned by these two productions, there has been a dearth of Gibson stories. That paradigm changed in 2017 with the opera The Summer King.

Not since Martina Arroyo entertained Howard Cosell on an episode of the 1970s sitcom The Odd Couple have the worlds of opera and sports blended to great appeal. “What? An opera about Josh Gibson?”1 recalls Christopher Hahn about the initial reaction to the idea. Hahn has been with the Pittsburgh Opera since 2000, serving as artistic director until 2008 and general director since then.

“Opera is about compelling stories of myths and legends told through music and action. What’s happening across America is a trend of opera companies exposing their audiences to a different range of subject matters in an attempt to engage audiences and communities in ways beyond Madame Butterfly and La Bohème,” Hahn says.

“People in this region are extraordinarily proud and very interested in all things Pittsburgh. It’s very different from other big metropolitan areas in that you’re living in a city with a small-town feel. Sports is one of the big fascinations and obsessions, but it is not so well-known that the theatrical community contributes to the life and pulse of the city.”2

Pittsburgh Opera is the seventh oldest opera company in the United States, but The Summer King was its first world premiere. It bridges the gap of knowledge for an arts culture that tends to think of sports as a diversion that neither informs nor elevates society. Sports fans got exposed to a subcategory of the performing arts that they tend not to be interested in. Forty percent of the single-ticket buyers for The Summer King had never bought a ticket to a Pittsburgh Opera performance before.3

Composed by Dan Sonenberg and directed by Sam Helfrich, The Summer King also benefits from contributions by Daniel Nester and Mark Campbell; Maine’s Portland Ovations launched the project with a trial concert reading in 2014.4 Pittsburgh Post-Gazette reviewer Robert Croan lauded the performance, highlighting Alfred Walker in the title role: “He can be tender in a love duet with his young wife Helen (bright and edgy coloratura Jacqueline Echols), heartbreaking in an aria describing her death during childbirth, and yet, in the second act, elicit the viewer’s admonition for the character’s dissolution and self-destructive behavior.”5

Additionally, 53-year-old Denyce Graves got high praise as Gibson’s girlfriend, Grace. “When this woman is on the stage, everything around her disappears into her own luminosity.”6

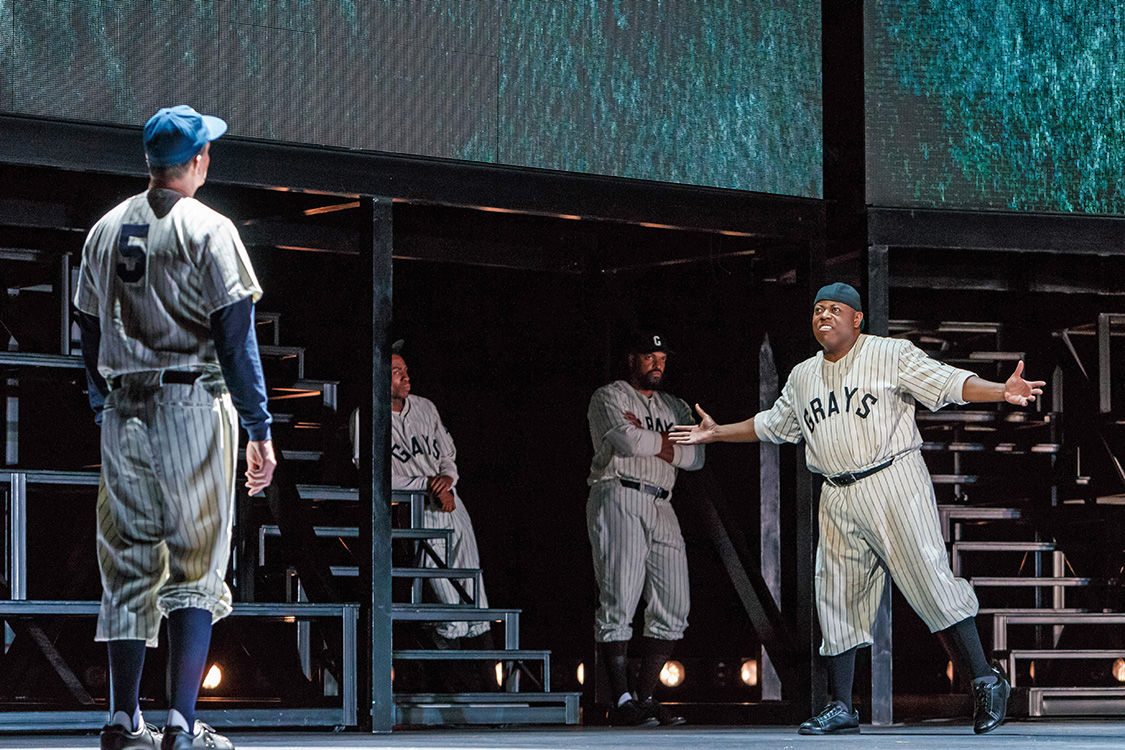

In this scene from The Summer King, Josh Gibson (played by Alfred Walker) hallucinates seeing Joe DiMaggio, and is agitated when DiMaggio doesn’t answer him. (DAVID BACHMAN PHOTOGRAPHY FOR PITTSBURGH OPERA)

The Summer King came to Hahn’s attention through the trade organization Opera America, which provides workshops for new productions. “When I started to say the name Josh Gibson around Pittsburgh, it got instantaneous recognition,” Hahn says. “In addition to the sporting community, there’s also a really powerful story of integration and social justice. It’s happening in the 1930s and 1940s with those aspirations.

“Gibson is a tragic character whose story is palpable. His wife died giving birth to twins. Though he was bereft, he had to raise them, which was a challenge when he was on the road playing baseball to earn a living. It’s a compelling story that he missed out on playing in the major leagues.”7

The opera also highlights Wendell Smith, the Pittsburgh Courier scribe later selected by Branch Rickey to be Jackie Robinson’s road companion and press conduit during Robinson’s rookie year of 1947—he wrote a column under Robinson’s name. In addition to baseball and the Courier, Pittsburgh’s black community had a prosperous cultural world that included the Crawford Grill, a cornerstone of black nightlife and a central location in The Summer King; when famous jazz artists came through the city, they often played there.

“There was a real sense of identity that was connected to the world of Negro League baseball. And what was really important to me was to address some of the complexity of the story because I think the most well-known narrative is the narrative of Jackie Robinson, how Jackie Robinson came along in baseball and integrated baseball and everything was sort of great after that,” says composer Sonenberg.

“What I wanted to convey here is that there was also something lost. There was this sense of community and identity that a lot of people had who belonged to the world of Negro League baseball and its surrounding cultural life in one way or another. And when baseball integrated which, of course, was a great thing that it happened, but a lot of these cultural institutions then began to fade away. Ultimately, the Negro Leagues themselves kind of completely disbanded by the end of the ’50s. They were no more.”8

There’s a scarcity of documented information about Gibson’s insights regarding baseball, racism, and the Negro Leagues. This presented both a challenge and an opportunity for Sonenberg to fill in gaps in public knowledge through research, lore, and creative license. In turn, he got a sense of the slugger’s persona. “Research was a long process. It was an on again, off again journey, but the more I worked on it, the more I gained a deeper understanding of the context of the Negro Leagues in the 1930s and 1940s,” he says. “Then, it became more and more clear to me how perfect a medium opera is to tell the scope of his story and the tragic component of it. From the start, I had an innate connection to the material.

“Josh Gibson still has not received his just acclaim. One of the real joys has been the response in Pittsburgh, where he’s celebrated as a hometown hero. It was my dream to have the opera premiere in Pittsburgh, so I think the idea that I was introducing this historical figure to opera fans not likely to know about him is to say that Josh Gibson is important to the city and important to all of us.”9

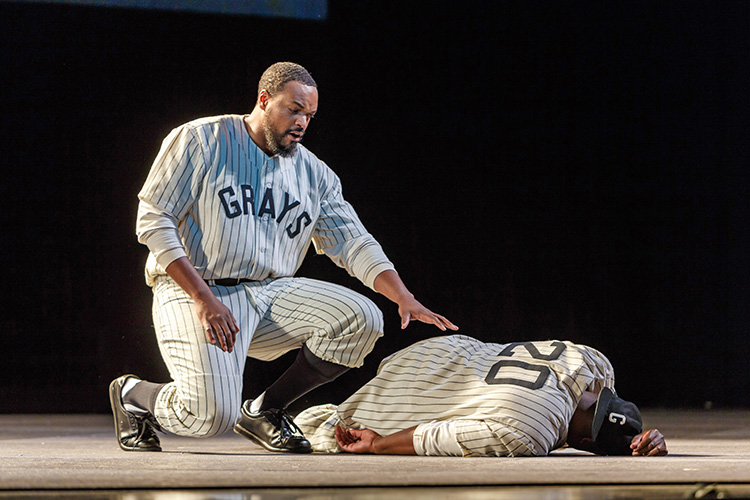

In this scene from The Summer King, Sam Bankhead (Kenneth Kellogg) mourns the death of his best friend Josh Gibson (Alfred Walker), who died at the age of 35. (DAVID BACHMAN PHOTOGRAPHY FOR PITTSBURGH OPERA)

To ensure the accuracy of family information in the opera, Sonenberg worked with the Gibson family. “When I heard about the idea, the first thing that I said was, ‘How is this going to work?’” says Sean Gibson, the slugger’s great-grandson, who leads the Josh Gibson Foundation. “So Dan came down to Pittsburgh and explained how he wanted to do the story. Ten years later, we had the world premiere.”

Sean Gibson says a lot of parents approached him in the lobby after performances to ask him about his great-grandfather. “I hope that when people leave the theater, they get a better sense of Josh’s life,” he says. “We helped Dan with some of the facts because we want people to know the family side of Josh. The opera tapped into groups that you usually don’t see at operas. African Americans. Teenagers. Children.”10

Born on December 21, 1911, in Buena Vista, Georgia, the future Hall of Famer—the second Negro Leaguer inducted after Satchel Paige—had a ninth-grade education. When he was 16, he began playing semipro baseball. A few years later, in 1930, according to legend, he came out of the stands at an exhibition game to replace Homestead Grays catcher Buck Ewing, who’d injured his hand. He was on his way to becoming the Steel City’s prince of power.11 When Gibson died on January 20, 1947, Smith wrote the obituary for the Courier, highlighting Gibson’s $6,000 salary being the second highest in the Negro Leagues, next to Paige’s. “There is no doubt that he would have been in the big leagues had it not been for the long and unjust ban against Negroes in organized baseball,”12 wrote Smith wrote.13

And the rest is history, revived in an art form that, at first, seemed questionable for its pursuit and now presents answers to dispel myths, enhance knowledge, and shed light on a corner of baseball history long since cloaked.

Bravo!

DAVID KRELL is the author of “Our Bums: The Brooklyn Dodgers in History, Memory and Popular Culture” (McFarland, 2015). “Our Bums” received Honorable Mention for SABR’s 2015 Ron Gabriel Award. In addition to “The National Pastime, David has written for the “Baseball Research Journal,” “Black Ball: A Negro Leagues Journal,” and “Base Ball: A Journal of the Early Game.” David is also a contributor to SABR’s Biography Project, Games Project, and Ballparks Project. David often speaks at SABR conferences and the Cooperstown Symposium on Baseball and American Culture.

Notes

1 Christopher Hahn, telephone interview, January 17, 2018.

2 Hahn.

3 Hahn.

4 Robert Croan, “Review: Pittsburgh Opera’s ‘The Summer King’ makes for thought-provoking performance,” Pittsburgh Post-Gazette, April 30, 2017. http://www.post-gazette.com/ae/music/2017/04/30/Pittsburgh-Opera-review-The-Summer-King-Benedum-Center/stories/201704300302.

5 Croan.

6 Croan.

7 Hahn, telephone interview.

8 “Daniel Sonenberg and Sam Helfrich,” Voice of the Arts, WQED Radio, April 28, 2017. https://wqed.org/fm/podcasts/voice-arts/daniel-sonenberg-and-sam-helfrich.

9 Daniel Sonenberg, telephone interview, February 9, 2018.

10 Sean Gibson, telephone interview, January 22, 2018.

11 “Josh Gibson,” National Baseball Hall of Fame and Museum, https://baseballhall.org/hall-of-famers/gibson-josh; Gibson’s SABR bio has Joe Williams as the injured catcher. Bill Johnson, “Josh Gibson,” SABR Biography Project, https://sabr.org/bioproj/person/df02083c.

12 Wendell Smith, “Grays’ Home-Run King Dies at 36,” Pittsburgh Courier, January 25, 1947.

13 Wendell Smith, “Grays’ Home-Run King Dies at 36,” Pittsburgh Courier, January 25, 1947.