George H. Lawson: The Rogue Who Tried to Reform Baseball

This article was written by Jerry Kuntz

This article was published in 2008 Baseball Research Journal

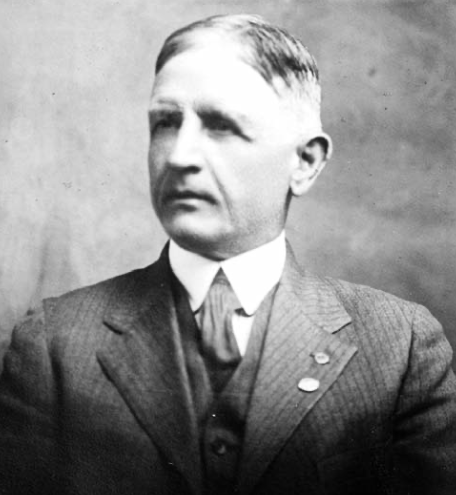

George H. Lawson (1864–1927), promoter of various baseball leagues, including the United States League, which drew attention for his announcement that he would sign African American players. After a modest launch in spring 1910, the league was disbanded in May, a few weeks into the season. (LIBRARY OF CONGRESS)

Few men appear to have been less qualified to take a stand against professional baseball’s greatest shame, the unwritten “color line” that segregated the sport for seventy years, than George H. Lawson (1864—1927). Lawson lived in the shadow of his more notorious brother, Alfred W. Lawson (1869— 1954), a longtime minor-league manager and promoter who, as a player, had a brief three-game stint in the weakened National League of 1890. Al Lawson was a restless, innovative, but mostly infamous figure in the baseball community between 1890 and 1916, thanks to his tendency to abandon players, teams, and leagues when his own interests were threatened. He eventually moved on to the fields of aviation, dietetics, philosophy, economic reform, and religion, building a following that some have labeled a cult. Alfred Lawson has often been cited as the foremost American eccentric—even his homespun system of physics (a component of the philosophy of “Lawsonomy”) included a key principle, “Zig-Zag-and-Swirl,” that posits that everything in the universe moves eccentrically.

George Lawson, Alfred’s brother, had less practical experience in baseball but tried to match his brother’s bluster as a promoter of new leagues. The evidence of those attempts made brief headlines between 1910 and 1926. However, recent research into George Lawson’s life has revealed a career full of aliases, criminal acts, debauchery, sociopathic tendencies, misogyny, quackery, and deception. In comparison, George Lawson makes his brother Alfred Lawson appear to be the soul of reason. Some small degree of recognition is due George Lawson for carrying the standard against racism in sport when so few others were willing to join him. However, his motives, as well as his actions after 1921, bring into question whether he can be credited with any real moral courage for his efforts to break the color line.

George Herman Lawson was born in the slums of London, England, in 1864, the son of Robert H. Lawson and Mary Ann Anderson Lawson. His mother’s maiden name, Anderson, was the source of the nickname he used for many of his baseball ventures: Andy Lawson. He also often used it to embellish his full name to George Herman Anderson Lawson. The family immigrated to Windsor, Canada, in 1869, and three years later moved to the Detroit area. When just sixteen, George H. Lawson left home and returned to his family’s old neighborhood in the East End of London. He soon enlisted in the British army and during the period 1881—86 served at postings in Ireland and India. He saw no fighting, but, like many of his fellow soldiers, he was hospitalized several times with gonorrhea and syphilis. He exhibited delusions of grandeur and was eventually diagnosed as “manic,” an archaic medical term that could signify a range of mental disorders. Interestingly, his medical record described his illness as inherited rather than due to venereal disease, suggesting a congenital personality disorder. He was sent to an asylum in India, then back to the major military hospital in England, and, finally, invalided out of the service in December 1886.1

AN EVENTFUL (BUT SKETCHY) BASEBALL CAREER IS LAUNCHED

Lawson returned to North America and married his first wife, Nana, in Ontario in March 1888. No evidence has yet surfaced that George Lawson participated in baseball before 1895, when he was 31 years old. In August of that year, George’s brother Alfred organized a team in Boston of “amateur” college players. Their intent was to tour England, playing against teams of the National Base Ball Association of Great Britain and the London Base Ball Association. Al Lawson recruited players allegedly from Harvard, Yale, and Princeton, but those schools have no records matching the names of Lawson’s players. The only non—Ivy League background of a player given to newspapers was that of an outfielder, George Anderson. However, one paper, the New York Times, reported the players’ names, replacing “Anderson” with his real name: George H. Lawson, “formerly of Ann Arbor University.”2 Not surprisingly, Ann Arbor University (as the University of Michigan was then informally known) has no record of George Lawson’s enrollment. Only one detailed box score out of the 19 games the Boston Amateurs played on this tour has come to light, and George is not in that lineup. Little, therefore, is known about his playing skills. The tour itself, which was originally to include 40 games and excursions into Scotland and France, scaled back its announced plans to 25 games. However, the tour collapsed within two weeks owing to low gate receipts. The Americans were surprised by the low ticket prices, as English baseball relied more heavily on club subscriptions rather than the gate. Poor publicity and hasty scheduling also contributed to the tour’s failure.3 Al Lawson, in typical fashion, had previously secured a ticket to Paris and used it, while his players were stranded without hotel money to tide them over until they could board their ship home.

George Lawson returned to his home in Boston, only to discover that his wife had left town in the company of another man. What then took place is a curiosity of nineteenth-century journalism. The Boston Globe ran a story that originated from Pittsburgh:

Geo. H. Lawson, manager of the amateur baseball team which went to England this summer, was in the city today with blood in his eye and a gun in his pocket He was about as angry a man as ever chased an absent wife, and as he boarded a train today for the windy city [he had tracked the fleeing couple first to Pittsburgh and then Chicago] he declared that he would continue the chase until some one got hurt.4

One has to wonder how a newspaper could report a crime that was merely threatened. Was a Globe reporter in Pittsburgh, and did he run into Lawson by happenstance? Or did Lawson himself wire the story to the Globe, thinking that his threats might eventually reach his errant spouse? At any rate, he appears not to have killed anyone, but Nana Lawson did ultimately divorce Lawson in 1897. Alfred Lawson, meanwhile, was mightily annoyed that his brother was misidentified in the Globe as the manager of the touring team, since that mention caused a misunderstanding between Al and a lady friend. It was the beginning of a public rift that divided the two brothers the rest of their lives.

At different points over the next two decades, both George and Alfred would deny that they were related to one another, although their reason could have been only to placate local citizens who had heard of the other Lawson’s baseball misdeeds. However, in some situations, George was quick to mention that he was the brother of a former major-league player. Sportswriters who learned of their relation assumed the two Lawsons colluded in their ventures, but the evidence suggests that George had none of Al Lawson’s baseball acumen and that George followed in his brother’s footsteps in order to see his own name in print and to capitalize on his brother’s occasional successes. For his part, Al Lawson seems to have viewed George as a pest who hounded his every baseball move.

The first example of this pattern occurred in 1897. That spring, Al Lawson organized an independent team in North Adams, Massachusetts, and tried to form a league in the Berkshires. Al Lawson’s “Lawsonites” played an impressive independent schedule, and he seemed to be a capable manager and owner. Meanwhile, across the state, George Lawson blew into Lawrence, Massachusetts, in mid-June and told reporters that he was organizing a team there and also would form a Merrimack Valley League. Local sporting men in Lawrence—and in the prospective league towns that George Lawson named—heard of these plans for the first time when they read them in the newspaper. George Lawson’s grand vision turned out to be just hot air.5

The next spring, both brothers were up to their usual shenanigans. Al Lawson secured a team for Manchester, New Hampshire, and made efforts to organize a New Hampshire League. Al Lawson’s Manchester team took the field for a few games in late April. Twenty-five miles to the south, George Lawson popped up in Nashua, New Hampshire. He secured a field there and also one in Concord, outflanking his brother’s moves to start a league. Frustrated, Al Lawson disappeared from Manchester with the gate receipts before the players’ May contracts started. George fielded a Concord team for a few weeks, and then he too threw in the towel. Later, in a Boston Globe article in 1923, sportsmen in Concord recalled:

When he [George] arrived he had with him an attractive young woman as his secretary, occupied a suite of rooms at the best hotel in town, leased the YMCA athletic grounds for a year, advertised for players, ordered handsome uniforms, announced that he would form a State League, and in various ways obtained a large amount of publicity. . . . Three or four games were played with teams from Laconia and Manchester [after Al Lawson had already left], but the gate receipts were not large either at home or abroad, and ‘Andy’ disappeared.6

Both Lawsons blamed their 1898 disasters on bad weather and a scarcity of players because of the Spanish—American War.

The Lawsons descended on Indiana in spring 1899. Al Lawson shaped a team for the town of Anderson and called together other unaffiliated town teams to form the Indiana-Illinois (Two-I) League. It started its schedule in early May. On May 27, Lawson took his team to play against Muncie and was distraught to find that Muncie was being managed by “George Anderson”—his brother George, using an alias. Their confrontation made headlines back east, where, the Boston Globe reported, with understatement, that “there had been ill-feeling between the brothers for some time.”7 The Two-I League dissolved in early June, and Al Lawson left Indiana to pursue a scheme to bring the first All Cubans team over to tour America. George, however, moved from Muncie and took control of the team in Kokomo, Indiana, which became a founding member of a more limited Indiana State League. George Lawson was unable to meet the team’s first payroll, and two of his players gave him a savage beating, forcing him to be hospitalized. When informed of George’s fate, brother Al was reported by the North Adams Transcript to be “evidently much disgusted with the lack of finesse shown by his brother in not getting out of town ahead of the game.”8 Perhaps he was just disgusted with his brother’s antics in general.

Chastened, George Lawson abandoned the field of sports for several years. He returned to Boston and in late 1899 married his second wife, Olivia. Lawson took up the occupation of selling sewing machines—a vocation that one of his other brothers, Donald Lawson, followed to become a regional sales manager for Singer. By early January 1902, Olivia Lawson had fled to the hinterlands of Boise, Idaho, and remarried within days of her arrival. In retrospect, it was probably the smart thing to do.

PROFESSOR LAWSON HERMANN, HYPNOTIST

George was impatient with the life of a salesman, and in 1901 he began self-study of another skill: hypnotism. In July, while still married to Olivia, he began an affair with a woman he met while selling sewing machines door-to-door. According to later court testimony, he made no sale but did convince Mrs. Della Carles (who herself was married) to take hypnosis lessons from him. They began a series of liaisons that occurred two or three times a week, sometimes overnight. Mrs. Carles tried to break it off over dinner at a restaurant. George flew into a rage and shoved her. The manager called the police. As Mrs. Carles fled, Lawson grabbed her purse. Lawson was arrested and charged—not for battery but larceny. He was sentenced to six months in jail.9

Imprisonment apparently only gave George Lawson time to hone his skills, for by the fall of 1902 he was touring the East Coast vaudeville circuit as a stage hypnotist. At every stop he publicized his engagement by sensationally announcing that he would bury a hypnotized assistant for a period of days—a stunt that necessarily involved trickery, since hypnotic “trances” last no longer than a normal sleep cycle. The papers of Boston, Philadelphia, Hartford, Wilmington, and Lowell abetted Lawson in his public-relations campaign as he appeared before city councils to get approval or defied police prohibitions against performing the burial stunt.10

In January 1903, “Professor Lawson Hermann” brought his act to the Passaic Opera House in New Jersey. He tried to recruit the wife of the theater manager to serve as his assistant. Though Mrs. Sohl appeared to be a willing accomplice, her husband objected. Mr. Sohl broke up a tryst between his wife and Lawson at Lawson’s apartment in New York City. Lawson then was booked to appear at another Passaic theater, the Empire. “Prof. Hermann” put his new male stooge, Samuel Powell, in a trance and inside a glass coffin on stage hours before the show. Meanwhile, word that Sohl was looking for Lawson “with ire in his eye and a revolver in his pocket” reached the “Professor,” and he failed to appear at his scheduled midnight performance. The New York Times reported:

The big audience became impatient, and manager Stein of the Empire became alarmed. The manager hustled around, and after some trouble secured Prof. Tony Frylinck. Prof. Frylinck worked all night before he could awaken the sleeper, and by that time the few weary spectators who had waited to see the upshot were so sleepy themselves that they had lost all interest in Powell, and some of those who had dozed off rather resented his return to consciousness of his surroundings, for Powell when he learned that Hermann had abandoned him was at first greatly alarmed and then waxed exceeding wroth, and expressed his opinion of the professor in language that was as loud as it was emphatic. He says he will never again permit himself to be buried alive.11

Lawson found a new female assistant, Helen Lenten, who became his third wife in 1903. In 1904, he brought his vaudeville act to Hartford, Connecticut. After a few performances, he and Helen settled in the city and he earned a modest living selling sewing machines from a storefront. During that time, Lawson hatched a much darker plan for using his hypnotic talents. He began to place in the Hartford papers ads claiming that “Prof. G. Hermann Lawson” could perform miracle cures for chronic medical conditions, and he scheduled appointments at his “sanitarium.” His practice, which probably consisted of dispensing placebos and hypnotic pain-control suggestions, proved to be lucrative. Soon he was waving around rolls of bills in local saloons. He paid for a new-fangled REO automobile in cash. He was arrested on two occasions for drunkenness, and one of those episodes resulted in bruises on Helen Lawson’s face and neck. The Hartford Medical Board finally caught up with Lawson in early 1906 and slapped him with an ineffectual $100 fine. Lawson kept on advertising, taking new patients, and appealed the fine. Creditors, not medical officials, finally forced the Lawsons out of Hartford.12 They moved south to Wilmington, Delaware, where they repeated the same scam. However, Delaware officials discovered his Hartford history and moved swiftly to charge him with medical malpractice. In February 1907, his first trial on those charges resulted in a hung jury.13 A month later, George Lawson assumed the name “James Anderson” and insinuated himself as the owner of the Greensburg club of the new Western Pennsylvania League. The president of this short-lived league was yet another Lawson brother, Alexander J. Lawson (who earned the nickname “Runaway Alex”—don’t ask).14 A few weeks into the season, on May 22, “James Anderson” disappeared from Greensburg, leaving the club broke.

To hedge his bets against being able to continue his career as a medical quack, George Lawson romanced one of his patients, Mary Gregg Chandler, the elderly, wealthy daughter of a former Wilmington sheriff. Lawson wasted little time in getting his marriage to Helen annulled on the basis that she had never legally divorced her first husband. He was then free to court the attentions of Mary Chandler. Simultaneously, he put out feelers for another baseball venture. In January 1908, George Lawson announced to Philadelphia papers that he was forming a new Pennsylvania—New Jersey League.15

George Lawson’s new league plans were preempted by a guilty verdict in his second retrial for medical malpractice, which resulted in a one-year prison sentence. Immediately after serving his sentence and being released from jail in March 1909, he married the heiress Mary Chandler. She was then 70 years old, he 45. She doubtless misjudged his true character, which didn’t take long to surface. In April 1909 he was arrested for beating her and putting a gun to her head to force her to write him a check.16 In September she filed for divorce.

UNITED STATES LEAGUE

Left to his own resources, George Lawson returned to Boston and a familiar enterprise. He announced the formation of the United States League in late December 1909 and made the astounding statement that he intended it to be an outlaw league (outside professional baseball’s National Agreement stipulations) that would ignore the color line and include black players on rosters of each team. In quick succession, Lawson announced that three members of the barnstorming Cuban (that is, African American) Giants would join the league’s Providence team and that Billy Thompson, an African American star of New Hampshire independent teams, would also be signed.17

Why did George Lawson take a stand against the color line? It was no secret in the sporting world that black players were talented and could play on a high level—such barnstorming independent teams as the Cuban Giants, Philadelphia Giants, and the New York Gorhams had proved that point. During the few weeks that he actually managed small-city clubs, George Lawson had signed at least one black player—Billy Thompson was a member of his Concord team of 1898. Lawson’s stint in the British army in India may have shown him that race was no measure of skill, strength, or courage. More likely, Lawson’s father, Robert Lawson, who had been a lay preacher from a section of London known for its reform politics, taught his sons the errors of prejudice. For whatever reason, Lawson did stake out a position, and many bigots heaped scorn on him, ridiculing the “Black and Tan League.”

There was no rush by African American players to join the United States League. Independent black teams (many of which were owned by whites) would have viewed Lawson as competition and discouraged their players from participating. Other early supporters of the United States League appeared to chafe at the increasing publicity given to the league’s integration. Efforts to place a franchise in Baltimore, or anyplace else south of the Mason-Dixon Line, were abandoned because of resistance by the local white establishment. Lawson’s shortcomings as an organizer were soon exposed. He had no head for business details, and for too long the league existed with no physical office. To the alarm of some of the prospective owners, Lawson agreed to the idea of letting players in the League unionize. On March 17, 1910, before any team had taken the field, the AFL recognized the players’ union.18 By late March, word of Lawson’s recent criminal history and his ex-con status likely forced his resignation as president of the United States League.19 The scandal proved too much for many of the backers to bear, and too much time had been lost. The league was scaled back to include only small New England cities, but it never captivated fan interest. The United States League of 1910 disappeared quietly in May, after a few weeks of play. Several of Alfred Lawson’s baseball cronies attempted to revive it in 1912. That effort failed too, after a slightly longer run. Veterans of that 1912 version went on to found the Federal League of 1913—15, which was a true attempt at a rival major league. In later years, George Lawson took credit for founding the Federal League, though he was at least two degrees separated from any connection to it.

WORLD WAR I AND THE ALLIED LEAGUE

Uncharacteristically, George Lawson kept his name out of public view during the period 1911—14. When World War I started, he was once again living in Boston and selling sewing machines from an outlet store. When war was declared, he was compelled to answer the call of his native country, Great Britain. He wrote to his old commander, the duke of Connaught, who was currently the governor-general of Canada, and volunteered his services. Despite his age (50) and ghastly service record in the British army (did they check, or were they that desperate?), George Lawson in 1914 was made the Boston recruiting officer of the Canadian Royal Engineers. He was soon transferred to Montreal, where he contributed to the war effort by helping to ferry men and cavalry horses over to England.

In later years he bestowed hero status on himself for his combat actions, but he mentioned only famous battles in which the Canadian Royal Engineers, notably, had no role. None of his World War I military records have survived, but a photo of Lawson in uniform displays the proper regimental insignia. His claim to have exited with the rank of sergeant major cannot be confirmed. George Lawson emerged from World War I in 1918 as a 54-year-old veteran. On arrival back in the United States, he picked up right where he had left off and announced that he was forming an Allied League, composed solely of war veterans. It was an idea with patriotic appeal, but Lawson was a poor organizer. He was only able to form one “Allied Veterans” team that played a few games against independent teams in Massachusetts and Rhode Island.20

In one of life’s ironies, a notable historical event that threatened to condemn Lawson to a fate he deserved miraculously released him. After returning home to Boston as a veteran, Lawson committed some unknown crime—probably while drunk and disorderly, possibly involving assault of a police officer— and was sent by the court to a state mental hospital, a sentence that courts of that time frequently imposed. Meanwhile, in September 1919, most of Boston’s police force walked off the job in a labor protest over abysmally low wages. Chaos resulted, and rioters wrought destruction on the Boston streets and citizenry. Order was restored by Governor Calvin Coolidge, whose staunch efforts to suppress both the rioters and strikers involved a directive to fire the striking policemen and to use National Guard troops to patrol the streets. Realizing that Boston needed to recruit a wholly new police force, Coolidge shrewdly reasoned that the best candidates were war veterans. He ordered vets confined for minor offenses to be paroled from prisons and asylums. The asylum doors opened to release George Lawson once more on an unsuspecting world. George Lawson was even motivated to run as an independent for the Massachusetts State Assembly against the incumbent local Democratic-machine candidate. His ballot-petition signatures were questioned in court, but his name remained on the slate on election day. He lost.21

CONTINENTAL BASEBALL ASSOCIATION

In December 1920, Lawson burst forward onto the national sporting scene with a proposal for a Continental Baseball Association (more often referred to as the Continental League), an outlaw major league with franchises in Massachusetts, New York, New Jersey, Maryland, Pennsylvania, Indiana, Ohio, and Michigan. Lawson stated that the CBA would use some of the same policies he had set out for the United States League in1910: It would be integrated, it would have no reserve clause and no salary limits, and it would endorse players unionizing and joining the AFL. Lawson’s CBA balloon captured perhaps more attention than his 1910 effort, for several reasons. First, the public still had not forgiven the established major leagues for the Black Sox betting scandal of 1919, which many blamed on the greed of owners. Second, Lawson argued that the stalwart combat service of American blacks had disproved the bias against them. Third, the African American community now had a stronger media network, with major newspapers in large eastern cities.

The sports pages of newspapers across the country in January and February 1921 issued new details about the CBA, seemingly on a daily basis. Lawson dropped big names left and right. He would sign seven of the eight Black Sox outcasts; he would lure Honus Wagner out of retirement; he would meet with George M. Cohan about ownership of one of the franchises (when informed that his name had been mentioned, Cohan’s response was a classic: “Piffle!”); and Lawson was also in talks with Casey Stengel. Very little of this appeared to be true, but, still, interest in the CBA seemed to grow almost despite Lawson’s blather.

This was probably due to the enthusiastic backing of major black newspapers, notably the Chicago Defender. In the New York News, the progressive black writer and lyricist Andy Razaf (Ain’t Misbehavin,’ Honeysuckle Rose) composed an ode:

Hail to the Continental League,

The Champions of a nobler plan,

Whose motto is “Democracy”

Whose aims are true American.

For they would save the nation’s game

And free it from a selfish few;

Who have dishonored it for gain

And barred the men of darker hue.

The Baseball Park is soon to be

A place where players, white and tan,

Shall demonstrate pure sportsmanship

And man will love his fellow man.

Where grandstand, box, and bleacher crowds

Will feel a new and greater thrill;

When pale and dusky Ruths and Cobbs

Will match their fleetness, nerve and skill.

Proclaim the news from coast to coast,

Let every true, red-blooded fan;

Support the worthy enterprise Of Andy Lawson and his clan!22

By early March, Lawson was clearly cultivating black support for the CBA. He promised not to raid the National Negro League, only a year old at that point, for players or to place teams in cities where the National Negro League teams operated. Unlike the situation in 1910, the National Negro League had black ownership, so Lawson was careful not to antagonize their interests, and he stated that he was willing to sign a mutual protection agreement. Plans changed rapidly. First, two entire teams out of the eight in the CBA would be all-black. By March 25, the ratio changed to 50—50, four black teams, four white teams. Two of the league officers, Robert L. Murray and Altamont James Stewart, were African Americans.23

However, while these developments were intriguing, white newspapers had dismissed the CBA by mid-March. All mention of George Lawson in connection with the Continental League stopped in mid-April. Many baseball histories wrote the Continental League off as another Lawson Brothers pipe dream that never took the field, and no evidence from the archives of white-run newspapers indicated anything to the contrary. However, on April 23, 1921, the Chicago Defender reported that the Philadelphia Continental League team had defeated the Knoxville College nine at an exhibition game in Knoxville. On May 7, the Defender stated that the League’s schedule had been finalized and that play would begin on May 15. On May 14, the paper ran a complete box score of an exhibition between the Boston Continental League team and the Chelsea Knights of Columbus. On May 21, the box score of a league game between the Boston Pilgrims and the Bronx Giants ran, and on May 28 a short mention was made of the scores of games between Philadelphia and the Bronx.24 After that, no more scores appear.

REVEREND LAWSON TAKES ON THE KLAN

George Lawson disappeared from media attention for a year and a half, but he began to make headlines again in December 1922. He had gotten religion and set himself up as a storefront evangelist in East Orange, New Jersey. On December 2, the New York Times reported that he had taken to the pulpit and publicly prayed to God to deliver him a bride. The story was picked up by papers throughout the United States, and Lawson was labeled as the “Prayer Bride” preacher. His nationwide search for a divinely provided spouse became a running story for nearly a month, and he was flooded with hundreds of letters from women offering themselves in matrimony. Lawson’s prayers were finally answered, in mid-January, when a plainfaced, devout, and poor laundrywoman named Ella Wieber took vows uniting her with George Lawson. She was wife number six. Their honeymoon was launched as a two-year national revival-meeting tour.25 Rev. Lawson’s evangelistic campaign got as far west as Cleveland before the money ran out. Lawson and his bride remained there for a year, and another Lawson sibling, Robert Lawson Jr., gave him a job as a painter and wallpaper hanger. In September 1924, the couple returned to New Jersey, settling in Ella Wieber’s hometown of Keyport. Lawson quickly built up large audiences for his street-corner sermons, where a hat was passed for collections. Through Ella’s connections, Lawson after a couple of months was able to secure the use of a vacant church, the Centerville Baptist Chapel near Keyport. There was one big catch: Members of the local chapter of the Ku Klux Klan controlled the chapel. Lawson willingly assented to the arrangement, and he gave several sermons in praise of the KKK. He was recognized as a Klan pastor and joined the organization.

In the mid-1920s, Klan membership throughout the United States reached its zenith, with many active chapters in the northeastern states. The revival of the Klan had been sparked by the 1915 release of D. W. Griffith’s Birth of a Nation, which glorified the Klan as an opponent of the evils of Reconstruction. In Northern states, the Klan’s membership swelled during a nationwide economic dip in the early 1920s, capitalizing on antiunion sentiment and “Red Scare” fears. There were complex motives for its popularity: Some of its leadership may have seen membership fees as a convenient pyramid scam, while others of its members may have viewed it as just another benign fraternal society. However, no one who listened to Klan rhetoric could ignore that its principles were racist, anti-Catholic, and anti-Semitic.

It did not take long for Lawson and his new masters to clash. Lawson claimed the local leaders had earmarked all the church’s collection money for a new Klan building and a new car for the local Kleagle. At the end of December 1924, Lawson resigned from the Klan and complained that he was being threatened.26 By the following March, the war of nerves reached a new height: Lawson declared himself a candidate for governor of New Jersey on an anti-Klan platform. In April, he defied Klan death threats and divulged to reporters all the local Klan’s passwords, oaths, and fees.

In mid-June 1925, Lawson had to be rescued by a squadron of state police officers after giving a campaign speech in front of a hostile crowd of a thousand Klan supporters in Keansburg, New Jersey. Signs in the Keansburg auditorium displayed Lawson’s campaign slogans: “Kan the Klan, Vote for Lawson,” and “Lawson, the Visible Foe of the Invisible Empire.” After taking the podium, he wasted no time launching into a deflating portrait of the KKK: “The members of the KKK,” he thundered, “are a gang of freight car thieves, rum runners, and stool pigeons.” He had to be whisked out the back door.27

A measure of the nation’s racial attitudes could be found in requests made in July 1925 to the Park Commission of Washington, D.C., for permission to hold rallies at the base of the Washington Monument. The Ku Klux Klan’s rally application was approved. George Lawson’s anti-Klan rally application was rejected. The reason given was that Lawson was a candidate for public office.28

After the election that fall (his name may have not even been on the ballot), George Lawson made news again for reverting to his old, bad habits. In late November, police were called to the Lawson residence because of a loud domestic dispute. An enraged Lawson threw dishes at the police chief and leveled a pistol at the arresting officers. While being booked, Lawson had to be clubbed into submission. He was charged with drunkenness and assaulting an officer of the law. At his hearing in January 1926, the judge scolded Lawson for his uncontrolled ego. Lawson begged for parole and promised to leave New Jersey—and even the ministry, if the court so ordered. Instead, he was just told to leave town.29

*****

George Lawson’s last public act came in December 1926. He was 62 years old and in poor health, with failing eyesight. His sixth wife appears to have left him. However, his indefatigable need for self-promotion was still intact: He called a press conference in New York City and announced the formation of the United States Baseball Association, a new major league. Only a few newspapers ran the story, and then only once.30 Lawson returned to house painting to earn a living. In February 1927, he fell from a ladder and suffered a cerebral hemorrhage from which he never recovered. He died in a hospital in Newark, New Jersey, on May 18, 1927.

At the time of George Lawson’s death, his brother Alfred was working just a few dozen miles away in the town of Garwood, New Jersey, on his latest and greatest aviation scheme. He had built the cabin for a gargantuan hundred-passenger aircraft and was trying to get the rest of the project funded. The “Lawson Superairliner” was his last stab in the field of aeronautics; it may be that his brother’s death helped turn Alfred’s attention to the reform of human nature, which he pursued for nearly thirty more years.

The last offense that George Lawson perpetrated on the public was his burial place. He was given a free plot and interred in the American veterans’ section of a Newark cemetery. Later, when officials checked records in order to erect a headstone for Lawson, they discovered that he had not served in the armed forces of the United States. No one bothered to relocate his body, and so George H. Lawson’s final resting spot is marked by an empty gap in a long row of white gravestones, emblematic of his many shortcomings and unrealized schemes.

JERRY KUNTZ is an electronic-resources librarian for the Ramapo Catskill Library System in Middletown, New York. He has recently completed a new biography of sharpshooter/aviator Samuel F. Cody, and is currently at work on a manuscript about Alfred and George Lawson.

Notes

- The British Army Royal Artillery Corps records of George Herman Lawson, 1881—86, including his service and medical records, were obtained from the British National Archives.

- New York Times, 11 August 1895.

- However, the Boston Amateurs made one lasting impact: The detailed box score of their game of September 3, 1895, against the London Consolidated club was used to illustrate scoring notation in the first British textbook of the sport, Baseball, written by the leading advocate of the sport, music-hall comedian Richard George Knowles.

- “One Town Behind: Lawson Is Following His Flying Spouse,”Boston Globe, 21 September 1895.

- “Andy Lawson’s Scheme,” The Sporting News, 26 June 1897.

- “Lawson Recalled by Concord Sporting Men,” Boston Globe, 5 January 1923.

- Boston Globe, 27 May 1899.

- “Al Lawson Here Again,” North Adams Transcript, 28 June 1899.

- “Why Lawson Stole,” Boston Globe, 23 January 1902.

- Lawson’s strategy to get publicity with the live burials worked to perfection in The Philadelphia Inquirer ran a series of articles detailing Lawson’s hypnotic claims and the reactions of police: Editions from October 21, 22, 24, 25, 26, and 31 and November 1 all ran stories.

- “Abandoned Sleeper in Coffin,” New York Times, 8 February 1903.

- Several years of reports of Lawson’s medical quackery culminated in “Lawson Decides to Quit Hartford,” an article in the Hartford Courant, 2 May 1906.

- “‘Professor’ Lawson on Trial Again,” Hartford Courant, 11 February 1907.

- Sporting Life, 9 March 1907.

- “And Yet Another Mushroom League in Pennsylvania,” Washington Times, 7 January 1908.

- “Wilmington News Notes,” Philadelphia Inquirer, 28 April 1909.

- “Boston to Be in New League,” Boston Globe, 29 December 1909.

- “Ball Player’s Union,” Boston Globe, 17 March 1910.

- “Lawson Leaves U S League,” Boston Globe, 30 March 1910.

- “Berkeley Trim’s Andy Lawson’s Veterans,” Pawtucket Evening Times, 9 June 1919.

- Boston Globe, 16 October 1919.

- New York News, 21 April 1921.

- Chicago Defender, 16 April 1921.

- Ibid., 28 May 1921.

- “Baseball Preacher Weds Prayer Bride,” New York Times, 14 January 1923.

- “Jersey Klansmen at Odds,” New York Times, 21 December 1924.

- “Anti-Klan Speaker Rescued by Police,” New York Times, 18 June 1925.

- “Permit is Refused Antiklan Gathering,” Washington Post, 8 July 1925.

- “Preacher Lawson Freed,” New York Times, 26 January 1926.

- “New Eight Club Ball League,” Chester Times, 20 December 1926.