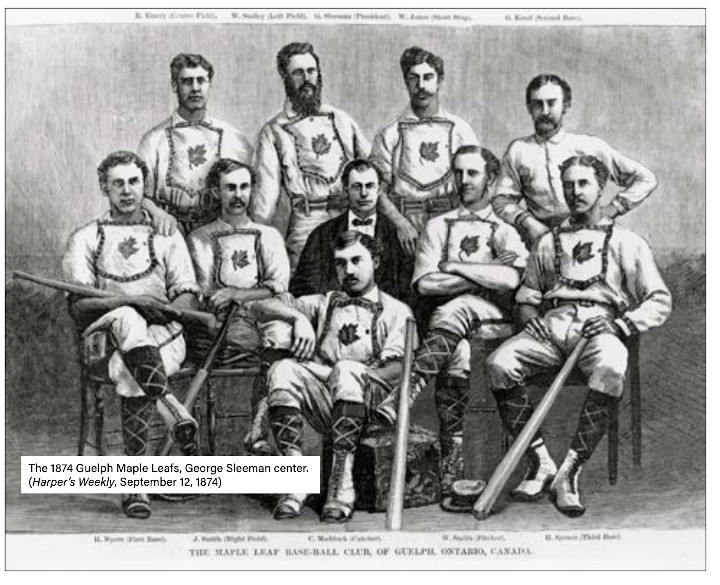

George Sleeman and the Guelph Maple Leafs

This article was written by Martin Lacoste

This article was published in Our Game, Too: Influential Figures and Milestones in Canadian Baseball (2022)

Baseball’s rise in the nineteenth century featured a storied cast of characters in a variety of locales. It is perhaps a reflection of the prototypically humble Canadian persona that the early “dynasties” north of the border were not from the larger metropolitan areas, but rather from less populous centers, notably a town (not even a city) that ranked 14th in population.1 And among the most significant figures was not a magnate or star player, but a young local businessman who later emerged as an influential leader in southwestern Ontario business, sport, and politics.

Nestled in the heart of southwestern Ontario, the town of Guelph was founded in 1827 and so was still in its infancy when the Sleeman family arrived in 1847. Among the newcomers was 6-year-old George Sleeman, the son of brewer John H. Sleeman and Anne Burrows. John was born in Cornwall, England, in 1805, and came to Canada in 1834 with his wife and three children. The family settled in St. David’s, Ontario (near Niagara Falls), and it was here that John built the Stamford Springs Brewery in 1836.2 George arrived five years later on August 1, 1841, their first and only child born in Canada.

In 1847, in search for a source of cleaner water, a crucial ingredient in the brewing process, John moved the family a full day’s ride northwest to the town of Guelph.3 After leasing a local brewery for three years, he purchased land in 1850 on Waterloo Avenue and built the Silver Creek Brewery, which opened the following year. He built a home near the brewery in 1859, and in this same year, son George took over the day-to-day operations of the brewery at the age of 18.4 By 1862, the brewery was renamed Sleeman and Son, and George undertook an even more prominent role in the family business.5 John retired from the brewery in 1867, and entrusted his son as sole owner. George’s involvement in the brewing trade continued throughout his life, but this did not preclude his pursuing several other passions, notably a significant interest in sport, particularly baseball.

His initial involvement in baseball may have occurred as early as 1861, as he recounted in a magazine article in 1923: “I was always a member of the [Guelph] Maple Leaf team, from the time it was formed in 1861 by A.S. Feast, who came from Hamilton.”6 He pitched for the Leafs in the early 1860s, but as the decade progressed and the team became more competitive, George transitioned from the playing field to a more managerial role.

Baseball in southwestern Ontario had been expanding greatly in the 1860s, as teams formed in Hamilton, London, Toronto, and Ingersoll, but none could unseat the Woodstock Young Canadians as Canadian Champions from 1865 to 1868. But by 1869, the Guelph Maple Leafs had established a solid core of local players, including pitcher William Sunley, veteran catcher James T. Nichols, second baseman Charlie Maddock, third baseman William “Bunty” Hewer, and 18-year-old shortstop Thomas Smith. The 1869 Championship for the Silver Ball, the trophy for the Canadian victors, was held in London in August, and pitted Guelph against the Ingersoll Victorias and the reigning champions from Woodstock. The championship game, which had to be rescheduled to September 24, resulted in a decisive 43-20 victory by the Maple Leafs over the London Tecumsehs. Woodstock was finally unseated as Canadian Champions, and Guelph retained this new title for another six years.

With the Maple Leafs as the new baseball dynasty into the 1870s, Sleeman was intent on further raising the profile of Guelph as the baseball capital of Canada. He also formed and managed a team “composed solely of home brews,”7 called the Silver Creeks, for whom he occasionally pitched. Games were held on an empty lot behind Sleeman’s brewery, and George paid for all expenses.8 Meanwhile, the reputation of the Maple Leafs continued to spread, as they accepted challenges from all comers from southwestern Ontario and New York state, and defeated such teams as the Dundas Independents, London Eckfords, Toronto Dauntless, Rochester Flour Cities, and Ilion Clippers.

In 1873, the “largest crowd ever assembled on the Maple Leaf ground” witnessed a game on August 22 between the Canadian champions and the “celebrated Bostons (champions of America).”9 The Boston Red Stockings were one of the top teams in the fledgling National Association of Professional Baseball Players, led by player-manager Harry Wright. It is perhaps ironic that the Leafs at this time were captained by former Red Stocking Sam Jackson, while the Boston team featured the first Canadian major leaguer, right fielder Bob Addy. Boston, with its legendary lineup that included no fewer than four future Hall of Famers (manager Wright in center field, his brother George Wright at shortstop, pitcher Al Spalding, and first baseman Jim O’Rourke), scored a decisive victory, 27-8, despite some “remarkably fine catches”10 by Guelph’s Tommy Smith and Johnny Goldie, and solid play by catcher Charley Maddock.

On April 7, 1874, the annual meeting of the Maple Leaf Base Ball Club was held, and George Sleeman was elected president of the club; as well, “motion was given for the creating of the office of Manager of the Nine, coupled with the name of Mr. Jas. T. Nichols,”11 a new position for which the duties “should be explained at the next meeting.”12 As president, Sleeman devised the Club Rules, and found a way to reward his players while maintaining their amateur status: Though no salary was paid, profits were divided up among the team members.13 The Leafs ventured successfully into international territory in 1874 on two fronts. In early July, at the Watertown (New York) tournament, they defeated all comers, including the Ku Klux Klan team from Oneida, New York, to take home the $500 prize. This success was due in no small part to the inclusion of a number of imports on the roster; Sleeman had signed several American players (second baseman George Keerl, from Baltimore; first baseman Hank Myers, of Ilion, New York; outfielder William A.Jones, aka William A. Silkworth, from New York; and third baseman Harrison Leslie Spence, also of New York). He imported more players the following year (William Bevan Lapham of Cincinnati and Johnny Foley), ensuring that the team would retain the Silver Ball Trophy as Canadian Champions in 1875.

In the meantime, while maintaining his management of the brewery and with the Maple Leafs, Sleeman somehow engaged in several other pursuits. He was elected president of the Guelph Turf Club in 1872 and remained in that position for over 20 years. A proud Guelphite, he became increasingly invested in civic matters, and was elected to the town council in 1876. All the while, he and his wife, Sarah Hill (married in 1863), continued to fill the rooms of the Sleeman home; soon after the end of the 1874 season, they welcomed their sixth child. (They eventually had 12 children.)

Sleeman sought to further elevate the status of baseball in Ontario with the formation of the Canadian Association for 1876. He was elected president of the Association and managed the Maple Leafs through another strong season. The highlight for the club was an exciting 9-8 victory over the National League St. Louis Browns in an exhibition game on August 29, William Squire Smith allowing only two runs over eight innings; the New York Clipper was less than effusive in its praise of the Leafs, declaring that they “played very steadily.”14 But with strong competition from rivals 75 miles to their southwest, the Leafs’ dominance came to an end as the London Tecumsehs were crowned champions of the Canadian Association.

Sleeman’s practice of importing American professionals had fueled much controversy and debate over the previous two seasons, and these were exacerbated during the 1876 season, as Sleeman continued to import more “amateur” players. This forced other teams to follow suit in order to remain competitive, and required teams and leagues to enact stricter rules to restrict the use of professionals in amateur leagues and contests.

With the success of the Canadian Association in 1876, Sleeman set his sights even higher in 1877; he sought to establish a fully international league that would also compete with the National League, then in its second year. Hence was born the International Association, wherein the London and Guelph clubs joined five American teams, but the Tecumsehs and Leafs followed very disparate paths. Though this did officially elevate the Guelph team to professional status (not to be confused with an amateur Guelph Maple Leafs team that also operated in the same season), the competition proved to be too much for both the team and Sleeman. He had to squash rumors in midseason of the team moving to Buffalo,15 and it was all he could do to finish the season. The Leafs posted a dismal 4-12 record to finish last, not taking into account the record of the Lynn Live Oaks, who disbanded in midseason. Guelph played its last league game against the Tecumsehs (who eventually followed as champions of the Association) on August 29, and despite a promising 6-1 lead after five innings, could not hold on, its season ending ignominiously with a 6-6 tie. This marked the end of close to a decade of Guelph superiority and success, and it was time for the club and Sleeman to move on.

Guelph did not return to the International Association for 1878. (And despite their tremendous initial success, even the Tecumsehs were only able to continue into August of 1878 before disbanding.) Rather, the Leafs languished as an amateur club, playing only sporadically over the next two seasons. Sleeman did not appear to have much involvement with the club at this time, but he did play right field for the Leafs on July 31 against the Harriston Browns. Sadly, on this same day, his older brother William died of a morphine overdose. From this point, perhaps as a result of this family tragedy, George seemed to relinquish any role with the Maple Leafs; the Guelph papers made little mention of him or the club for the remainder of the season. He kept a low profile until he was named chairman of the inauguration committee when Guelph became a city on April 23, 1879.16 He focused his energy more on civic matters, having gained such respect and popularity locally that he was elected the first mayor of the City of Guelph (by acclamation) in January 1880.

Mayor Sleeman returned to baseball for the 1880 season, as president of a new Canadian Association, which adopted the same constitution as the previous incarnation from 1876.17 Teams from Galt, Toronto, and Woodstock, and a pair from Guelph (Maple Leafs and Athletics) vied for the Amateur Championship of Canada, but played only a handful of games. By season’s end, both the Leafs and Woodstock Actives claimed they were entitled to the championship bat.18 While the Actives’ claim was justified by their 1-0 victory in the championship match on September 8, Sleeman and the Leafs asserted that “during the early part of the season, [they] vanquished all comers,”19 and that the two losses they incurred at the end of the season (as well as a 3-2 loss on August 27 to the Harriston Browns) were under protest, as both the Actives and Browns had, in a stroke of irony considering Sleeman’s prior management philosophy, “introduced professionals into their teams.”20 The final decision of the judiciary committee has not been found.

The Maple Leafs returned to independent amateur play in 1881, with Sleeman still as president. In an otherwise unremarkable season, another Sleeman signing caused yet another controversy. In early July, amateur pitcher John W. Jackson, known professionally as Bud Fowler, was engaged by the Maple Leafs, but “when he reached Guelph and the members of the club found he was a coloured youth, they snobbishly refused to play with him.”21 The Guelph Herald expressed its disappointment with the team’s reaction, and could only take solace in finding “that it is only a few members of the team”22 who objected to Fowler’s engagement.

Over the next two years, Sleeman was more preoccupied with civic duties, having been reelected mayor of Guelph for both 1881 and 1882. He was asked to run yet again in 1883, but declined. The Maple Leafs saw little activity during this time, until 1884, when they resurfaced as a member of the Western Ontario Baseball League. This new amateur league consisted of 10 teams, including two from Guelph, and three each from Hamilton and London. Sleeman was elected a director of the league, but appears to have had little to do with league or team operations. But this set the stage for perhaps his most ambitious baseball project yet, when he was elected president of the newly formed Canadian League for 1885. The Leafs, with Sleeman returning as their manager, joined the Hamilton Clippers, Hamilton Primroses, London Cockneys, and Toronto Torontos to play out a full season of approximately 40 games.

However noble his intentions, Sleeman reignited the flames of controversy yet again when he signed Cincinnati pitcher George Washington Bradley. Bradley had been under contract with the Philadelphia Athletics since 1883, and was suspended for having left to join the Cincinnati Unions. And as the Canadian League constitution “[forbade] the employment by League clubs of players under contract with or expelled from any other club,”23 other teams protested on the grounds that Bradley he was an ineligible player. But Sleeman insisted on putting Bradley in to pitch on July 9 against London, contending that he was indeed eligible, as the Canadian League was independent of the American Association. Regardless, the Cockneys refused to play, umpire Fred Goldsmith called the game, and a protest was filed. This scenario was repeated on July 11 in a scheduled game against Toronto. The Judiciary Committee met on July 14 in Hamilton to decide the affair, and despite its feeling that Sleeman had “acted conscientiously for what he considered to be in the interests of the Leaf Club,”24 it “could not endorse the club playing Bradley”25 and ruled against the Leafs. Sleeman “gave it as his opinion that a mistake had been committed, and that the Leafs were dealt with unfairly and unconstitutionally, and in consequence he thought the Leafs would go out of the League.”26 Three weeks later, it was reported that the Leafs management had decided to disband. The Hamilton Spectator expressed its disappointment: “The Maple Leafs started out with a fine team of local players; but the other league teams were strengthened beyond the calibre of the local players, and it was principally to the endeavor to keep up with the procession that the Leafs owe their present position. Hard luck, too, had a great deal to do with it.”27 The announcement proved premature, because Sleeman resigned as manager, which left “the boys [to] run the machine themselves,”28 but his “liberality and his love for baseball [were] again demonstrated”29 when he allowed the Maple Leafs free use of his ground and stand in order to “finish the season with profit to themselves.”30 “In face of the fact that Mr. Sleeman lost a large sum of money on baseball this year, the generous offer shows that he is willing to make great sacrifices for the good of the sport in Guelph.”31 Third baseman James H. Hewer took over managerial duties, and the Leafs managed to finish the season. But despite players of major-league caliber such as Louis Bierbauer, Dennis Fitzgerald, Mickey Jones, and Edward Kent, they finished in a battle for last place (with a record of 8-28) with the equally hapless Hamilton Primroses.

Sleeman, still president of the Canadian League, sought to put the challenges of 1885 behind him, and at the annual meeting on November 30 in Toronto, was reelected league president as plans were made for the coming season. Meanwhile, the “formation of an International League by affiliation with the New York State League was discussed,”32 and this indeed came to fruition, with Toronto and Hamilton (Clippers) withdrawing from the Canadian League to join the newly renamed league. Sleeman filed suit against the Canucks and Clippers, to no avail, but, undeterred, secured a “first-class team for the coming season, and lovers of the game in Guelph may rely on having a good nine placed in the field.”33 Considering the success that was to come, it is worth taking a brief look at the players Sleeman brought together to form the most victorious team that Guelph ever fielded.

Two of those who remained with the club formed the catching tandem. A 21-year-old Guelph native, Andrew Dillon, worked as an upholsterer, and showed promise as a young catcher, touted as “one of the coolest and gamest catchers in the country”34 by the Kalamazoo Gazette. He played in the Northwestern League in 1887 and for Lima in the Tri-State League in 1888, but died of typhoid and pneumonia only two years later.

James “Son” Purvis, from Port Hope, Ontario, had played with the Milwaukee reserve team in 1884, but returned to Canada in 1885 and played for both Guelph and London of the Canadian League. He enjoyed a lengthy career playing with Buffalo and London of the International League, as well as with clubs from Grand Rapids, Rockford, Peoria, and Des Moines. He finished with the Hartford Cooperatives of the Atlantic League in 1898, and thereafter, raised a family and worked as a cabinetmaker in Grand Rapids, Michigan. He died there in 1935.

Longtime Maple Leaf James Hewer played several infield positions with Guelph until 1896. A prominent businessman and merchant, he was elected mayor in 1897, and many Guelphites mourned his passing in 1916.

Sleeman brought in rising star Albert C. Buckenberger of Detroit to manage and play second base for the Leafs. He had been captain of the Cass Club of Detroit for three seasons, and had most recently played with Indianapolis, Terre Haute, and Toledo. He achieved greater fame as a manager for nine seasons in the majors, with Columbus of the American Association (1889-1890) and in the National League with Pittsburgh, St. Louis, and Boston between 1892 and 1904. He died in Syracuse in 1917.

As did Buckenberger, first baseman Wally “Jumbo” Millar, born in Jackson, Michigan, also played with amateur clubs in Detroit for several seasons. He impressed Sleeman very early on and was named Leaf captain. He returned to Sandusky in 1887 and managed the club several years later. He died in Detroit in 1935.

William George, born in Bellaire, Ohio, played primarily right field and shortstop with the Leafs, but also pitched in eight games. His brief turn on the mound got the attention of the New York Giants, who signed him as a pitcher for the following season. He pitched in 19 games in the majors with New York and the Columbus Solons of the American Association, then returned to the outfield in the minor leagues until 1899. His playing days over, he returned to Bellaire and operated a billiards parlor, then a saloon, before succumbing to peritonitis in 1916.

Benjamin Stephens of Pittsburgh (born Stephani in France) played first base and pitched on occasion for Guelph in 1886, having played the previous season with Macon of the Southern League. He spent the next several seasons playing in the Northwestern, Tri-State, and New York-Pennsylvania leagues, primarily as an outfielder. He continued to tend bar in Pittsburgh but troubles with alcohol led to a severe case of delirium tremens, and eventual death in 1906 at the age of 51.

Frank Scheibeck, from Detroit, also with the Sanduskys in 1885, was brought in by Sleeman to play shortstop and pitch for the Leafs. He enjoyed a lengthy career in baseball, including stints in London (International League) in 1888-89 and Montréal (Eastern League) from 1898 to 1901, and spent several years in the majors from 1887-1906 with seven teams. He was the last surviving member of the team when he died in 1956 in Detroit.

Scheibeck primarily alternated pitching duties with Harry Zell, who was born in Dayton, Ohio, and who, along with Stephens, had played with Macon in 1885, leading the Southern League in fielding. He played with Buffalo of the International League in 1887, then played for several other minor leagues before ending his career in Dayton in 1892. He owned and operated a saloon in his hometown, and died in 1912 after a long illness at the age of 47.

From the Sanduskys as well, Sleeman enticed third baseman Dan Mulholland, who had gained fame for his unassisted triple play against the National League Detroit Wolverines. He was one of the top hitters for the Leafs in 1886, but returned to play for Sandusky in 1887. He played a few more seasons before retiring to his hometown of Norwalk, Ohio, where he ran a saloon and later became a solicitor. He died in 1927.

Owen “Reddy” Williams had been a teammate of William George with the Bellaire Globes, and played left field for the Maple Leafs. He went on to play for Milwaukee of the Northwestern League in 1889, then played for several seasons in the Tri-State League. He spent his later years as a glassworker in Ohio and West Virginia, and died in 1929 in Fairmont, West Virginia.

The Leafs’ stalwart center fielder was Charles “Count” Campau, who had played with Buckenberger on the Detroit Cass Club. He was an “itinerant minor-league star who played for teams in at least 19 cities, including three stops in the majors.”35 He had played with Erie, Pennsylvania, in 1885 until that club disbanded, then finished the season with the London Tecumsehs. His first major-league tour was with the Detroit Wolverines in 1888, but it was his second stint in the majors that was his most successful, when he joined the St. Louis Browns of the American Association as player-manager in 1890. Despite an impressive record of 27-14 as manager, he was nevertheless replaced, but stayed on as a player. And although he hit an impressive .322 in 75 games and led the league with nine home runs, he was released by Browns owner Chris Von der Ahe with two weeks remaining in the season, in an effort to cut costs.36 He returned to the majors four years later, but appeared in only two games with the Washington Senators. He umpired for a few seasons in the minors, then left baseball altogether to work at racetracks tracks across North America. He died of pneumonia in 1938.

With Sleeman’s team in place, the Leafs barnstormed their way through Ontario and the United States, highlighted by an American tour in August that proved tremendously successful. They played top amateur clubs from Michigan, Indiana, Ohio, Virginia, and Pennsylvania, achieving a record of 23-1, and by September 1 their overall record stood at an exceptional 43-1. A mediocre final month still resulted in a formidable season record of 53-9, without question the greatest season enjoyed by the Maple Leafs.

Despite the successes, the Leafs underwent yet another dramatic transition, with an entirely new club in 1887. They merged with the Guelph Royal Oaks, and it was mostly former Oaks who comprised the 1887 Maple Leafs. Sleeman, essentially retired from the game by this time,37 remained as honorary president, while former Guelph pitcher William S. Smith assumed the role of club president.38 Considering the many changes, the local press was less than optimistic about the coming season: “Is the glory of the once champion Maple Leafs now allowed to be a thing of the past?”39 This would prove prophetic, as the Leafs played only sporadically over the next several seasons.

Though honorary president, George Sleeman no longer held an active interest in the Maple Leafs.40 Without his leadership, but with his blessing, the club soldiered on. It returned to organized play in 1893 as a member of the Canadian Amateur Baseball Association, then in 1894 finished first in the Western Ontario Baseball League, and repeated this the following year as a member of the Western League of the Canadian Baseball Association. A second iteration of a Canadian League was formed in 1896, including teams from Galt, Hamilton, London, and Guelph, and once again the Leafs finished first, with a record of 24-12. The 1896 roster featured two young local stars: Jimmy Cockman, younger brother of 1885 Leafs shortstop Tommy Cockman, played many years in the minors before finally reaching the majors in 1905 as a 32-year-old rookie to play 13 games at third base with the New York Highlanders; and William “Bunk” Congalton, who played with the Chicago Orphans in 1902, then with Cleveland and Boston from 1905 to 1907. His brief career was highlighted by a stellar season with the Cleveland Naps in 1906 in which he batted .320, which would have put him fourth in the AL had he had four more plate appearances. The Leafs and manager James Hewer returned to the Canadian League in 1897, but finished last of the three teams that remained by season’s end. There is no trace of the Leafs during the 1898 season, but they rejoined the then Class-D Canadian League for the 1899 season. Manager George Black guided them to an unremarkable record of 42-48.

The heyday of the Maple Leafs now years behind them, they played in amateur versions of the Canadian League in 1904 and 1905. By 1908, the former International League (or Association) operated as the Class-A Eastern League, and this allowed four teams from Ontario and New York, including Guelph, to form a Class-D International League. But the Guelph franchise shifted to St. Thomas, Ontario, on June 12, and the league itself disbanded at the end of July.

Professional baseball returned to Ontario in 1911, as George “Knotty” Lee formed a new Class-D Canadian League. The league remained relatively healthy through 1915, by which time it had attained Class-B status. The Maple Leafs themselves achieved moderate success in the first three seasons, and after a sabbatical in 1914, returned, managed by Lee, to finish a very respectable second to the Ottawa Senators in the league’s final season. This was the last year the Guelph Maple Leafs played at a professional level, though Lee once more brought professional baseball to Ontario in 1930 with the Class-D Ontario League; by this time, however, the Guelph team went by the nickname Biltmores.

With his role in baseball now relegated to that of an ardent fan, Sleeman became involved in several other areas of Guelph daily life. He had been an expert marksman, one of the best rifle shots in Guelph, and he was president of the Guelph Rifle Association from 1886 to 1906. He also delighted in winter sports, being named president of the Royal City Curling Club in 1888. When Mayor Thomas Goldie, also a former Guelph Maple Leaf, died suddenly in 1892, Sleeman agreed to take over and finish Goldie’s term.41 In 1894 George started the Guelph Railway Company, which constructed one of the first electric railways in Ontario.42 His father, having returned to St. David’s to enjoy a peaceful retirement working on his gardens, died early that year.

Sleeman returned to the mayor’s office in 1905, elected by an all-time majority, a reflection of his stature in the community. By this time he had retired from the family business and erected the Springbank Brewery, which he conducted until his death.43 He continued to be held in high regard in his city: He ran for mayor one last time in 1906, and won uncontested.

After his wife, Sarah, died in early 1917, George continued to surround himself with family and friends, being known by many for his hospitable nature.44 Entering his 80s, he remained in excellent health, and his sense of citizenship and community pride never waned. His passion for sport, notably baseball, remained undiminished: “It is worthy of note that in his last conscious moments his thoughts were about some of the men who were players of that famous baseball team.”45

Sleeman died after an abdominal operation on December 16, 1926, in Guelph General Hospital, and was laid to rest in Woodlawn Cemetery, a few miles from where still stands the old Sleeman Manor, near the site of the original brewery and ballpark. His grave is perhaps fittingly modest and not a reflection of his impact, with only a simple flat stone marker that simply states “George Sleeman, husband of Sarah Hill,” along with his dates of birth and death. Dubbed the “father of professional Canadian baseball for his role in the early organization of the game,”46 he and his impact were more fully acknowledged when he was elected to the Canadian Baseball Hall of Fame as a builder in 1999.

MARTIN LACOSTE has taught high-school music for over 30 years, but has always had a passion for baseball, whether fondly recalling the Expos from the 1980s or digging into the Maple Leafs from the 1880s. Having been a SABR member in the 1990s, he is excited to again be a member (in the digital era) since 2016.

Sources

In addition to the sources cited in the Notes, the author consulted:

Newspapers, including Guelph Herald, Guelph Mercury, Hamilton Spectator, London Advertiser, London Free Press, Maple Leaf, New York Clipper, Toronto Globe, and Woodstock Weekly Sentinel.

Ascenzo, Denise. “Niagara’s History Unveiled: The Early Years,” https://www.niagaranow.com/entertainment.phtm-l/1266niagarashistoryunveiledtheearlyyears, accessed July 7, 2021.

Bernard, David L. “The Guelph Maple Leafs: A Cultural Indicator of Southern Ontario,” Ontario History (Toronto: Ontario Historical Society), September 1992.

Matchett, Micheal. “The Sleeman Family Brewery: 19th Century Paternalism to Prohibition-Inspired Myth,” Historic Guelph, the Royal City (Guelph: Guelph Historical Society, 1993).

Genealogical and player data was obtained from a variety of sources, including Ancestry.com, Baseball-Reference.com,census records, FamilySearch.org, vital records, minor-league player files of Reed Howard, and the author’s own player database and genealogical files.

Various ledgers and correspondence from the Sleeman Family Collection, Archives and Special Collections, McLaughlin Library, University of Guelph.

George Sleeman, email correspondence with Murray Inch (descendant), 2020-21.

Notes

1 Census of Canada, 1870-71 (Ottawa: I.B. Taylor, 1873), 428.

2 “Timeline: Sleeman Family History and Events,” https://www.lib.uoguelph.ca/archives/our-collections/regional-early-campus-history/sleeman-collection/timeline-sleeman-family.

3 “The Early Days: The Silver Creek Brewery,” https://www.lib.uoguelph.ca/archives/our-collections/regional-early-campus-history/sleeman-collection/brewing-history/early-days.

4 “Timeline: Sleeman Family History and Events.”

5 “Timeline: Sleeman Family History and Events.”

6 “The Maple Leafs of Guelph,” Maple Leaf, Guelph, January 1923: 13.

7 Old Timers Will Remember Those Famous Silver Creeks Who Played ‘Way Back When Gloves, Masks and Pads Were Not Known,” Guelph Mercury, July 20, 1927: 90.

8 “Old Timers Will Remember Those Famous Silver Creeks Who Played ‘Way Back When Gloves, Masks and Pads Were Not Known.”

9 “The Base Ball Match,” Guelph Mercury, August 23, 1873:1.

10 “The Base Ball Match.”

11 “Maple Leaf B.B.C. Annual Meeting,” Guelph Mercury, April 8, 1874:1.

12 “Maple Leaf B.B.C. Annual Meeting.”

13 Maple Leaf Baseball Club Ledger (1874-76), Sleeman Family Collection, Archives and Special Collections, McLaughlin Library, University of Guelph.

14 “St. Louis vs. Maple Leaf,” New York Clipper, September 9, 1876:186.

15 “Base Ball Notes,” Guelph Mercury, July 19, 1877: 1.

16 “Death of Mr. George Sleeman Removes Prominent Pioneer Business Man of Royal City,” Guelph Mercury, December 16, 1926: 1.

17 “Base Ball,” Guelph Mercury, May 12, 1880: 1.

18 “The Return of the Actives,” Woodstock Weekly Sentinel, September 17, 1880: 4.

19 “The Canadian Championship,” Guelph Mercury, October 14, 1880: 2.

20 “The Canadian Championship.”

21 “Base Ball,” Guelph Mercury, July 27, 1881: 2.

22 “Guelph’s Colored Pitcher,” Hamilton Spectator, July 4, 1881.

23 “Bradley’s Status,” Hamilton Times, July 8, 1885.

24 “Meeting of Judiciary Committee,” Guelph Mercury, July 14, 1885: 1.

25 “Meeting of Judiciary Committee.”

26 “Meeting of Judiciary Committee.”

27 “The Maple Leafs,” Guelph Mercury, August 11, 1885: 1.

28 “The Maple Leafs.”

29 “The Maple Leafs in Luck,” Toronto Globe, August 25, 1885: 8.

30 “The Maple Leafs in Luck.”

31 “The Maple Leafs in Luck.”

32 “The Canadian Baseball League,” Guelph Mercury, December 4, 1885: 1.

33 “Baseball,” Guelph Mercury, March 8, 1886: 1.

34 “Baseball,” Guelph Mercury, August 16, 1886: 1.

35 Stephen V. Rice, “Count Campau,” SABR BioProject, https://sabr.org/bioproj/person/count-campau/.

36 Rice.

37 Lisa Bowes, “George Sleeman and the Brewing of Baseball in Guelph 1872-1886,” Historic Guelph (Guelph: Guelph Historical Society, October 1988), 55.

38 “Guelph Baseballers,” Guelph Mercury, May 10, 1887: 4.

39 “Local News,” Guelph Mercury, April 30, 1887: 1.

40 Unattributed clipping from the Sleeman Family Collection, Archives and Special Collections, McLaughlin Library, University of Guelph.

41 “Death of Mr. George Sleeman Removes Prominent Pioneer Business Man of Royal City,” Guelph Mercury, December 16, 1926: 9.

42 “Death of Mr. George Sleeman Removes Prominent Pioneer Business Man of Royal City.”

43 “Death of Mr. George Sleeman Removes Prominent Pioneer Business Man of Royal City,” Guelph Mercury, December 16, 1926: 1.

44 “Death of Mr. George Sleeman Removes Prominent Pioneer Business Man of Royal City,” Guelph Mercury, December 16, 1926: 9.

45 “Late Geo. Sleeman,” Guelph Mercury, December 16, 1926:4.

46 “George Sleeman – Canadian Baseball Hall of Fame,” http://baseballhalloffame.ca/blog/2009/09/17/george-sleeman/.