Guy Bush: That Guy From Pittsburgh

This article was written by Matthew Clifford

This article was published in The National Pastime: Steel City Stories (Pittsburgh, 2018)

During a professional baseball career of 18 seasons spread out over a span of 23 years, Guy Terrell Bush only spent one full season and part of another in Pittsburgh. But with bloody fists and a heart filled with frustration, he left a few marks in the baseball history books while wearing Pirates flannel. In the span of a few weeks in 1935, he was a key figure in two of the most memorable moments of the decade for the Bucs.

During a professional baseball career of 18 seasons spread out over a span of 23 years, Guy Terrell Bush only spent one full season and part of another in Pittsburgh. But with bloody fists and a heart filled with frustration, he left a few marks in the baseball history books while wearing Pirates flannel. In the span of a few weeks in 1935, he was a key figure in two of the most memorable moments of the decade for the Bucs.

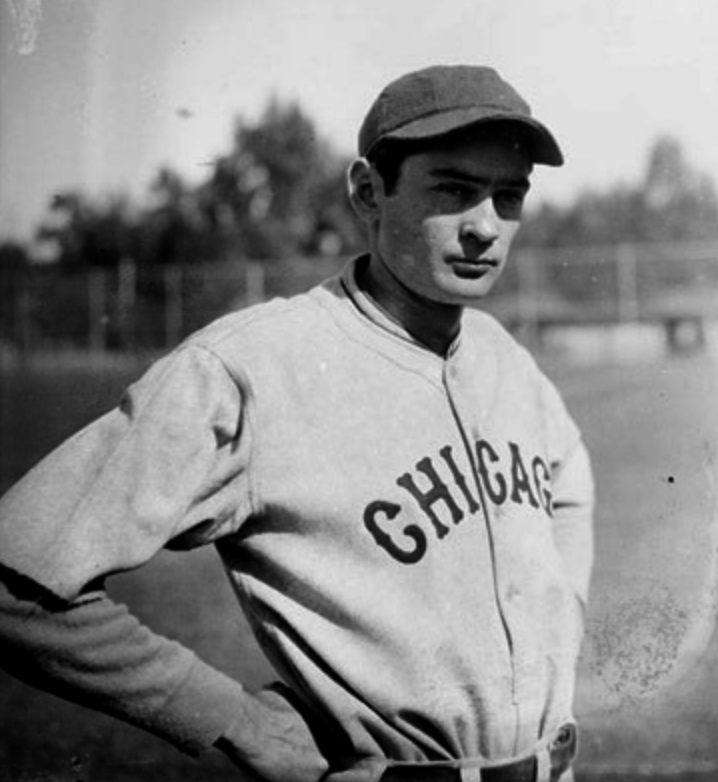

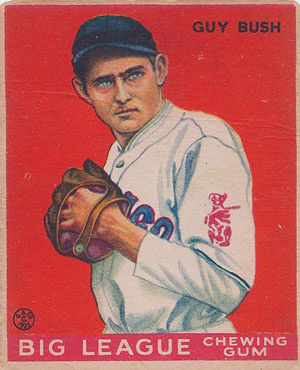

Old-time fans recall Bush’s nickname as “The Mississippi Mudcat,” after a breed of catfish that occupies the murky waters of the Mississippi Delta. Bush’s Chicago Cubs teammates gave it to him when they learned he was born in Aberdeen, Mississippi, and had pitched for the Tupelo Military Institute. The 22-year-old made his debut for the Cubbies on September 17, 1923.

Between 1924 and 1933, Bush was regarded as one of the team’s most reliable hurlers. He appeared in two World Series as a Chicago employee, in 1929 and 1932. In 1934, though, he butted heads with Cubs manager Charlie “Jolly Cholly” Grimm, who became frustrated with Bush as he struggled through June and July with a strained muscle in his left side and then an ear infection.

The bad blood between Grimm and Bush became clear during one weekend in August when most of the Chicago team gathered for Grimm’s birthday celebration. Bush chose to skip the party due to personal commitments involving his gas station businesses. He sarcastically requested his teammates to advise Grimm that he was unable to attend as he needed to supervise the gasoline pumps “to make sure his customers’ tanks were filled properly.” The business relationship between Bush and Grimm became more and more difficult as the ’34 season scraped to an end with the Cubs finishing third, eight games out.

Bush finished with an 18-10 record with the Cubs. He was involved in a car accident in Chicago during the late weeks of October and suffered a few minor cuts and bruises. While he was healing at home, he received news that he had been traded to the Pirates. The details of the big deal made the sports papers in late November: Grimm agreed to part with pitchers Bush and “Big” Jim Weaver and outfielder Babe Herman in exchange for stellar southpaw Larry French and veteran outfielder Freddy Lindstrom.

After the dismal 1934 season he’d shared with Grimm and the Cubs, Bush was excited to bid farewell to the Wrigley Field mound. Fueled with resentment, Bush told the press, “You don’t know how tickled I am to join the Pirates, whom I consider the greatest club in the world. I can hardly wait for the season to start and I will be rarin’ to go when it does.”1 A few months later, Bush packed his bags in Chicago and headed for spring training in California to meet with his new boss, Pie Traynor, and the rest of his Buccaneer teammates.

Bush befriended rookie pitcher Cy Blanton during spring training and the two became travelling roommates throughout the 1935 season. Bush was ready to give the Pirates everything he had, especially when the NL schedule led the Pirates to meet up for a duel with his old boss, Charlie Grimm, and his Chicago Cubs. The meeting took place at Wrigley on April 29, and the brutal incident would forever be remembered as “The Battle of Chicago.”

The game became interesting in the fifth inning after Pirates infielder Harry “Cookie” Lavagetto hit a double to score player/manager Traynor from second to give the Pirates a 6–2 lead. As Lavagetto was sliding into second, he felt the spikes of shortstop Billy Jurges. The Pirates’ dugout cleared out, led by Bush. The Chicago bench cleared too and the brawl began.

Bush swung at Cubs pitcher Roy Joiner. His punches led to bloody injuries to Joiner’s nose and jaw. Three Pittsburgh teammates held Bush back while the rest of the team fought with the Chicago boys. One of the men holding Bush in place was pitcher Hal Smith, who cut a finger on his right hand in the process. Blanton also sustained a spike injury to his foot, but he was unable to determine if his offender was a Cub or a Pirate. Jurges and Lavagetto exchanged punches as the Wrigley crowd went wild. Joiner was dragged back to the dugout and Grimm assessed his injuries. Noticing a deep gash in Joiner’s jaw line, Grimm insisted that the ghastly slice had come from a blade held by his ruthless ex-employee, Guy Bush.

The umpires went over to Bush, who was being calmed by the warm dirt of the Wrigley infield on his back and three of his Pittsburgh cohorts sitting on top of him. It was quickly determined that the Mississippi Mudcat wasn’t in possession of a knife. The six-inch cut to Joiner’s jaw was possibly made by a sharp ring on Bush’s right hand. The exciting event was frowned upon by Commissioner Kenesaw Mountain Landis, who witnessed it from his box. Umpires Bill Klem, George Magerkurth, and George Barr eventually calmed the brawl and ordered all players back to their dugouts. Some profanity continued and all were threatened with ejections if their foul mouths continued. Lavagetto and Bush were ejected, along with their Chicago opponents, Joiner and Jurges. National League President Ford Frick suspended the quartet for several games and fined them all.

The game continued, but Traynor was in a predicament. Two of his pitchers were injured, another was ejected, and his starter, Waite Hoyt, was getting tired in the seventh inning. Traynor put in Jack Salveson to relieve Hoyt and four Chicagoans ran the four corners around Salveson. The battle ended with a score of 12–11 in favor of Grimm’s determined Cubbies. Bush left Wrigley Field with more hard feelings—and proof of his bad blood with Chicago stained on his Pittsburgh flannel.

The sportswriters scribbled about the Battle of Chicago throughout the 1935 season and Bush was inevitably noted as the villain. “The affair between the Pirates and the Cubs here at Wrigley Field may have started because there was a jam around second base between Bill Jurges and Harry Lavagetto,” read one report in The Sporting News. “But it reached full bloom because only a spark had been needed to touch off the pile of resentment that Guy Bush had been accumulating toward Manager Charlie Grimm.”2

After completing his suspension, Bush returned to the Pirates’ lineup in early May. A few weeks later, he made the headlines again when another old rival came to Forbes Field: Babe Ruth.

After completing his suspension, Bush returned to the Pirates’ lineup in early May. A few weeks later, he made the headlines again when another old rival came to Forbes Field: Babe Ruth.

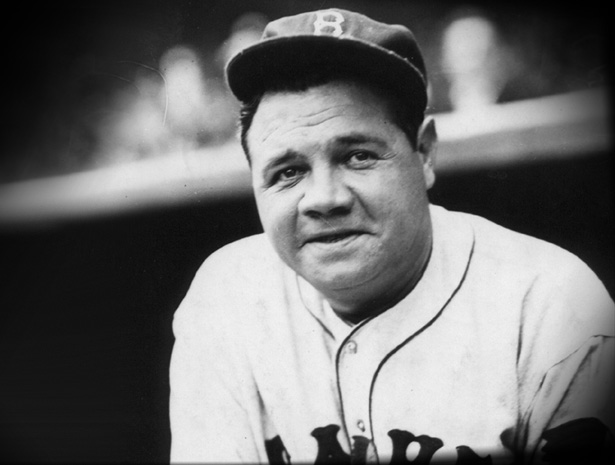

The last time Bush had seen Ruth, Bush was wearing his Chicago garb in the 1932 World Series against the New York Yankees. Bush had been one of Ruth’s most vicious bench jockeys. After Game Three, which would come to be known as the game of Ruth’s “called shot,” Bush happily admitted that Ruth was yelling back at him moments before the Bambino pointed to Wrigley’s center field. Decades after the called shot, Bush hand-wrote his recollection of the historic event to an autograph seeker: “Ruth was talking to me. At the time when he raised his right hand it is of my belief he pointed to center field. The only thing I am sure of he hit the next pitch in center field stands.”3

Guy’s written statement was corroborated by a letter handwritten by Ruth’s New York teammate, Joe Sewell, who was also present to witness the called shot. Sewell wrote, “Babe Ruth never said a word to Charlie Root the pitcher, but he was cussing Burley [sic] Grimes Bob Smith and Guy Bush who was on their bench cussing Ruth. When he got two strikes on him he got out of the box with two fingers on his right hand he pointed to the centerfield, and on the next pitch he hit the homerun.”4

The day after Ruth’s called shot, Bush’s personal frustration against the Babe was still scalding. During the fourth and last game of the series, he intentionally hit the Babe with a wild pitch. Regardless, the Yankees swept the Cubs to claim the 1932 championship. Three years later, Bush and Ruth would meet again.

The Sultan of Swat had switched leagues and uniforms in late 1934, hoping to gain a management position with the Boston Braves of the National League.

Bush was more than ready to take the mound and put the Bambino to bed. Traynor put Charles “Red” Lucas on the hill to start the game and the Babe’s first plate appearance resulted in a home run, the 712th of his career. The fanatics at Forbes Field went wild. Bush got his wish to take the hill after that. Traynor pulled Lucas and sent in the Mississippi Mudcat. Bush kept the Braves quiet for the remainder of the first inning. The atmosphere changed when Ruth stepped up to swing against Bush in the third inning. Guy threw as fast as his right arm would allow and Ruth smashed a home run with Braves second baseman Les Mallon on base. The Braves were ahead of Pittsburgh 4–0. Furious that his name had been added to the long line of Ruth’s pitching victims, Bush growled as he closed the third inning.

The Pirates shared Bush’s determination in the bottom of the fourth. Braves hurler Huck Betts couldn’t stop the Pittsburgh boys and the score was tied 4–4. Bush met with Ruth again in the fifth inning and the Babe hit a single to score Mallon from second for a 5–4 lead. The Pirates pushed back and ended the fifth inning ahead 7–5. The teams stayed blank in the sixth. The golden ink of the history books began to glow in the top of the seventh when the Babe stepped in the box and stared at Bush perched on the Forbes mound. Bush tossed Ruth a strike, followed by a screaming fastball to the outside corner. His second twirl couldn’t escape a kiss from Ruth’s legendary bat. The ball shot high above Bush’s head and disappeared over the right-field wall. No player in the history of Forbes Field had ever hit the ball that far out of the park. The Sultan of Swat had hit his 714th career home run. It was the last one that George Herman “Babe” Ruth would hit. Bush recalled the details of Ruth’s home run finale in a 1985 interview. “As he went around third, Ruth gave me the hand sign meaning ‘to hell with you.’ He was better than me. He was the best that ever lived.”5 Traynor pulled Bush off the mound after he let two more Braves on base. Despite the fever and excitement Ruth brought to Pittsburgh, the Pirates won the game 11–7.

The Pirates shared Bush’s determination in the bottom of the fourth. Braves hurler Huck Betts couldn’t stop the Pittsburgh boys and the score was tied 4–4. Bush met with Ruth again in the fifth inning and the Babe hit a single to score Mallon from second for a 5–4 lead. The Pirates pushed back and ended the fifth inning ahead 7–5. The teams stayed blank in the sixth. The golden ink of the history books began to glow in the top of the seventh when the Babe stepped in the box and stared at Bush perched on the Forbes mound. Bush tossed Ruth a strike, followed by a screaming fastball to the outside corner. His second twirl couldn’t escape a kiss from Ruth’s legendary bat. The ball shot high above Bush’s head and disappeared over the right-field wall. No player in the history of Forbes Field had ever hit the ball that far out of the park. The Sultan of Swat had hit his 714th career home run. It was the last one that George Herman “Babe” Ruth would hit. Bush recalled the details of Ruth’s home run finale in a 1985 interview. “As he went around third, Ruth gave me the hand sign meaning ‘to hell with you.’ He was better than me. He was the best that ever lived.”5 Traynor pulled Bush off the mound after he let two more Braves on base. Despite the fever and excitement Ruth brought to Pittsburgh, the Pirates won the game 11–7.

Five days after the hurrah at Forbes Field, the Babe appeared in his last major-league game. At Baker Bowl in Philadelphia on May 29, he struck out twice off Syl Johnson of the Phillies. The following day, Ruth stepped to the plate one last time in Philly to face “Gentleman” Jim Bivin. The Bambino grounded out. He trotted off the field to the clubhouse and never appeared in another major-league game. Ruth announced his retirement to the press on June 2. Johnson later confessed that he tried to hand Ruth “easy ones” on May 29. He’d hoped to gain the same notoriety Bush had earned a few days before. It seemed that everyone (with the exception of Bush) wanted to witness Ruth collect another home run. Four years later, on June 12, 1939, Johnson got another chance to repeat his offering to Ruth at the first Hall of Fame game at Doubleday Field in Cooperstown. The Babe swung at Johnson’s pitch and popped it up high for the fans, but it was caught by exhibition catcher Arndt Jorgens.

Without the sensational exceptions of being Ruth’s last victim and the only Pirate accused of bringing a knife on the diamond, Bush’s 1935 highlights with Pittsburgh lacked the luster of his years with the Cubs. The Mississippi Mudcat’s 1935 record of 11-11 and ERA of 4.32 were disappointing. His rookie roommate, Blanton, received accolades from the press for his 1935 season and the young hurler credited the tips Bush had passed down to him. Blanton told the press, “Whatever I’ve accomplished this year has been through the efforts of Guy Bush.”6

Bush kept his Pittsburgh flannel for four more months in 1936. He appeared in 16 games and posted a 1-3 record before playing his last game with the Pirates on July 15. Five days later, the Pittsburgh club released the Mudcat to the wild, and the Brooklyn Dodgers had their baited poles in the waters. But Bob Quinn, boss of the Boston Bees, as the Braves were now called, snatched the pitcher before Brooklyn’s hook could intervene. Bush signed with Boston on July 23 and took his place on the mound soon after the contracts were completed. But his once reliable right arm was not so reliable. He went 4-5 in 16 games. Bees skipper Bill McKechnie kept Bush on the 1937 roster, hoping his arm would return to its old Chicago form. It did not. In February 1938, the Bees told Bush to buzz off and the Mudcat was picked up by the St. Louis Cardinals. But on May 7, 1938, less than a month into the season, the 36-year-old Mudcat was thrown into the murky waters of the minor leagues after six appearances and an 0-1 record.

The Cubs’s Pacific Coast League affiliate, the Los Angeles Angels, took Bush to finish their 1938 season. He left baseball in 1939 to focus on his ownership of gasoline stations in Chicago, which would soon suffer the effects of World War II fuel rationing. In 1944, the baseball itch came back and the hurler was picked up by the Chattanooga Lookouts, a minor-league club owned by the Washington Nationals. At 42, Bush was the oldest member of the team. The Mississippi Mudcat got one more chance in the majors in 1945, when he was signed by his old boss McKechnie for a spot on the Cincinnati Reds’ roster. Bush stayed with the team briefly, hanging up his glove after four appearances.

Guy Bush threw his last major-league pitch on May 26, 1945. He returned to Chicago and ran a sporting goods supply business in addition to managing his gas stations. In 1973, sportswriter Bob Broeg interviewed Bush, who complained that current major-league pitchers were feeding easy tosses to Hank Aaron, then getting close to breaking Ruth’s home run record. Broeg teased Bush about his historical link to Ruth. “With piercing black eyes, shallow complexion, long sideburns, plastered black hair, sporty clothes and a racy car, Guy Bush looked like a Mississippi card shark transplanted in the 20th century,” Broeg wrote. “But he was a good pitcher and a great competitor. He was a good, hard-working and, yes, a colorful righthander who won 176 games, 40 more than he lost in 13 full major league seasons and parts of three more seasons.”7

The old Mudcat retired from his gas station and sporting goods careers and eventually made his way back to Mississippi, where he settled in the town of Shannon. While he was tending his backyard garden on July 2, 1985, Bush suffered cardiac arrest and died. He was 83 years old.

In 2001, the Donruss Trading Card Company released the “Timeless Treasures” collection, which included a card that commemorated Babe Ruth’s final magnificent moments at Forbes Field. The card, recognized as number 2 in the series, featured a black-and-white photo of the Bambino on the right half. Though Ruth was playing for the Braves on that day in Pittsburgh, the card bears a Yankees logo and he wears his Yankees uniform in the photo. On the left side of the card is a tiny wooden piece of a seat that had been in Forbes Field in 1935. The back of the card includes this description: “The enclosed piece of stadium seat was cut from an Authentic Stadium Seat used in an official Major League Baseball Game at Forbes Field on May 25, 1935 in which Babe Ruth collected his final home run.”8 The card continues to hold value: It was being offered on eBay at $73 and up in April 2018.9

The card’s worth almost certainly stems from Ruth’s name and photograph. But it might not even exist if it hadn’t been for a skinny, hot-headed Mississippi pitcher and his stubborn animosity against a baseball Sultan who had swatted his final home run deep into the Pittsburgh skies in 1935.

MATTHEW M. CLIFFORD is a freelance writer from the suburbs of Chicago, Illinois. He joined SABR in 2011 to enhance his research abilities while helping to preserve accurate facts of baseball history. His background in law enforcement studies and forensic investigative techniques aid him with historical research and data collection. He has reported several baseball card errors and inaccuracies of player history to SABR and the research department of the National Baseball Hall of Fame. He is also a contributing writer for SABR’s BioProject. Feedback is welcome at his email address: matthewmclifford@yahoo.com.

Acknowledgments

Special thanks to fellow SABR biographer Gregory K. Wolf for his detailed literary BioProject contributions of Guy Bush and Cy Blanton. Personal thanks to my son Thomas D. Clifford for fact checking. Thanks to Retrosheet, Paper of Record, Cooperstownexpert.com, Old Fulton Postcards, and Baseball-Reference.com, and to Cecilia Tan for the opportunity and her painstaking efforts organizing and editing.

Notes

1 “Buc Fans Put Okay On Deal With Cubs,” The Sporting News, 29 Nov. 1934, Pg. 2.

2 “Scribbled By Scribes,” The Sporting News, 30 May 1935, Pg. 4.

3 “Guy Bush,” Big Six Sports, http://www.cooperstownexpert.com/player/guy-bush. Grammatical and punctuation errors in handwritten note sic.

4 “Guy Bush,” Big Six Sports, errors sic.

5 “Guy T. Bush,” The Sporting News, 15 Jul 1985, Pg. 57.

6 “Blanton Credits Guy Bush, Pal And Roomie, For Success,” The Sporting News, 16 May 1935, Pg. 3.

7 “Bush’s Not-So-Fond Memories,” The Sporting News, 21 Jul. 1973, Pg. 4.

8 “Final Home Run, Forbes Field, Babe Ruth,” Timeless Treasures Card TT-2, Donruss Trading Card Co., 2001.

9 Search result, eBay, April 22, 2018. https://goo.gl/eJBcYy