Hack Wilson: A Pugilist

This article was written by John Racanelli

This article was published in The National Pastime: Heart of the Midwest (2023)

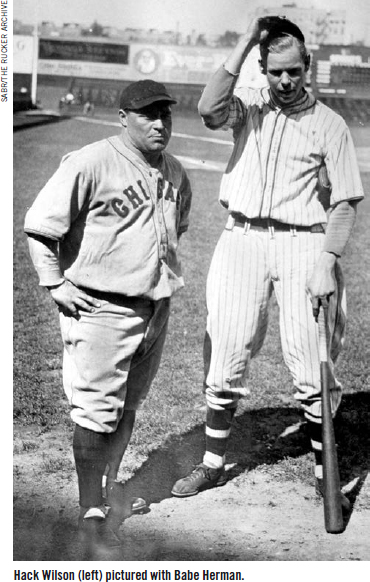

“During his career in Chicago, Hack [Wilson] has indulged in four fistic encounters. All of the battles have tended to increase his popularity. Most ballplayers would be called rowdies or hoodlums for such outbreaks, but there is something about Hack’s gladiatorial foray that makes the folks cheer instead of condemn. That is, folks who have not been targets for the pudgy one’s onslaught.” —Edward Burns1

Unthinkably, just a year removed from hitting 56 home runs and knocking in 191 runs, Cubs outfielder Hack Wilson was persona non grata in Chicago. Thanks to a mediocre 1931 campaign and a season-ending suspension in September, he and pitcher Bud Teachout were traded to the Cardinals for 38-year- old spitballer Burleigh Grimes in December.2 Wilson, however, was insulted by St. Louis’s salary offer and refused to sign.3 The Cardinals shipped him to Brooklyn in January, where he settled for $16,500 (approximately $360,000 today)—precisely half of his 1931 salary with the Cubs.4 Determined to show he was still a valuable Major League slugger, Wilson found himself fighting for his career. But Hack Wilson was no stranger to a fight.

A MILKMAN GETS CREAMED

Near the end of an afternoon doubleheader at Wrigley Field on June 21, 1928, Hack Wilson grounded out to second base. Edward Young heckled Wilson from the grandstand, “When’ll you bench yourself, you fat so and so!?”5 Wilson did not appreciate the unsolicited advice and leapt into the stands where he reportedly “thump[ed] Mr. Young soundly before other players pulled him off.”6 Young claimed two other Cubs, Gabby Hartnett and Joe Kelly, also took some jabs at him during the melee despite having “ostensibly entered the box as peacemakers.”7

Young, a milk wagon driver, was arrested for having incited a riot and pled guilty to a charge of disorderly conduct.8 Wilson did not face criminal charges but was fined $100 by National League president John Heydler for “conduct unbecoming a ballplayer.”9

On July 25, Young filed a personal injury lawsuit against the Cubs and Wilson, alleging, somewhat ironically, that the Cubs owed a duty to protect him against “disorderly persons” so he might “peacefully enjoy the game.”10 He sought damages of $50,000 (approximately $855,000 today) but would have to be patient for his day in court.11

FIREWORKS ON INDEPENDENCE DAY

The Cubs hosted the Reds for a doubleheader on July 4, 1929. In the fifth inning of the second game, Hack Wilson rapped a seemingly ordinary single off Pete Donohue. As Wilson stood at first base, Reds pitcher Ray Kolp ridiculed him with taunts of “bastard” and dared him to come into the dugout.12,13 Wilson obliged—fists flying. He landed a blow on Kolp’s jaw that even the Reds’ hometown paper called a “neat piece of work.”14

Once order was restored, Wilson and Kolp were ejected. Donohue, tagged for four earned runs in four innings, got the hook—but it would not be the last time he was roughed up that day. The Cubs and Reds gathered at Chicago’s Union Station to catch the (same) train that would take the Cubs east to Boston and Reds to Pittsburgh, and the teams mingled near the gate. Still fuming, Wilson warned he was going to “make Kolp apologize.”15 Kolp, however, had arrived early and had “retired immediately to the privacy of his Pullman.”16

As Wilson was talking peacefully with Reds pitcher Jakie May, Donohue butted in, “You’re quite a scrapper, aren’t you? If you want any more, come into our car.”17,18 Wilson saw no reason to wait, and popped Donohue where he stood, knocking him to ground. Members of both teams jumped in to pull the men apart and railroad officials diplomatically separated the teams into different sections of the train.

Wilson was unapologetic afterwards, “I’m no Dempsey, but when anyone says I’m yellow I am going to try to show ’em they’re wrong. Kolp thought I wouldn’t take his dare to come into the dugout after him Thursday. He didn’t want to fight. He just wanted to make a little noise.”19 Wilson was fined $100 and suspended for three days by the National League. However, club president William Veeck took no disciplinary action against Wilson, whom he considered a “gentleman and conscientious baseball player.”20 Veeck added, “Boys will be boys, you know.”21

THE MILKMAN RETURNS FOR ROUND TWO

When Edward Young’s lawsuit was dismissed in October 1929 on procedural grounds, the Cubs and Hack Wilson likely felt some sense of relief. However, Young’s attorney acted quickly to reinstate the matter. An amended complaint was filed in November in which Young’s claims against the Cubs were dropped. The revised pleading named Hack Wilson as the sole defendant and reduced the ad damnum to $20,000 (approximately $350,000 today).22

Wilson’s response to the amended complaint included a plea of son assault demesne, in which Wilson claimed that if Young had been injured in the altercation, Wilson had acted in self-defense—an awfully creative theory considering Wilson and several other Cubs had crossed into the grandstand to confront Young.23

HACK WILSON: PROFESSIONAL PRIZEFIGHTER?

On December 14, 1929, news broke that Hack Wilson had agreed to face White Sox first baseman Art “The Great” Shires in a four-round fight. The bout would pay Wilson a guaranteed $10,000 and training expenses.24 He finally appeared poised to cash in on his pugilistic prowess, which had brought him “nothing but fines and suspensions,” plus pending civil litigation up to this point.25

Art Shires’ amateur “record” included a pair of fist- fights with his White Sox manager, Lena Blackburne, during the 1929 season.26 Shires also had an official professional bout under his belt, having knocked out “Dangerous” Dan Daly in 21 seconds—a fight that ultimately brought Shires a suspension by the National Boxing Association due to accusations it had been fixed.27,28

Shires ridiculed Wilson for having lost a ball or two in the sun during the 1929 World Series, “Hack will think he is looking into the sun again, when I start throwing them at him. The fact he belongs to the National League, which really is a minor league, doesn’t prod my Major League pride.”29 Even Ray Kolp weighed in on the Wilson-Shires saga, “Hack is a pushover for me any way you take it. He can’t get a hit off my pitching in a month, and he wouldn’t do any better with his fists.”30

In a match billed as a tune up for the Wilson bout, Shires squared off against Chicago Bears center George Trafton on December 16. Trafton knocked Shires down twice in the first round and again in the second. The remainder of the five-round fight exposed the pair for their lack of conditioning, and Trafton eventually won by decision. Following Shires’ embarrassing loss, Wilson decided to pass on the fight, “if Shires had beaten Trafton I might have gone to Chicago and tried to talk president Veeck of the Cubs into letting me go through with it. But there is no use in bucking the Cubs and making my wife mad just to floor a guy who has already been licked.”31

Regardless, Art Shires kept fighting.32 On January 10, 1930, Shires scored a four-round technical knockout against Braves catcher Al Spohrer in Boston. Following his victory, Shires bellowed, “I didn’t want Al Spohrer. I wanted Hack Wilson!” to the 18,000 fans in attendance.33

“I want Shires twice as bad as he wants me,” Wilson replied as he reconsidered travelling to Chicago to plead for the Cubs’ blessing to pursue the fight.34 That Wilson’s guarantee had been increased to $15,000 (nearly $270,000 today) may have also played a factor.35

National League president Heydler weighed in on the matter, “We don’t want to interfere with the offseason activities of our men any more than we can help, but when these activities threaten our investment in the man and the man, himself, it is time to call a halt…it has taken them so long to get where they are and yet they want to jeopardize this position for a few dollars.”36 This was rich, considering Wilson’s expected payday nearly equaled his $16,000 salary for 1929. On January 25, however, Judge Kenesaw Mountain Landis dealt the death blow to any potential Wilson-Shires match, “Hereafter any person connected with any club in this organization who engages in professional boxing will be regarded by this office as having permanently retired from baseball. The two activities do not mix.”37 Though the Shires fight (and payday) was no longer in the cards for Wilson, he still had one battle to attend to before leaving for spring training at Catalina Island.

THE MILKMAN (FINALLY) HAS HIS DAY IN COURT

Trial in the case of Edward Young v. Hack Wilson was called on February 11, 1930, in front of Superior Court Judge William Fulton and a twelve-man jury in Chicago. Wilson seemed unconcerned, “It’ll be a surprise if he wins the suit and an even bigger surprise if he collects it.”38

When it finally came time for Young to testify, he admitted he heckled Wilson, “You big tub! Why don’t you bench yourself?”39 Wilson then leapt into the stands, knocked him down, and tossed him over a seat. As a result of the attack, Young suffered facial injuries requiring stitches and back pain so severe he was unable to work for several weeks.40 Young, however, confessed that he had consumed a “few seidels of beer” (while Prohibition was in full swing), and—under examination by his own attorney—admitted he “could not say whether [he] was drunk or sober at the time.”41,42

Hack Wilson took the stand and testified, “the vile names [Young] shouted at me were unbearable and my fighting blood naturally reached a boiling point, but I did not hit him.”43 Instead, Wilson described how he fell en route to confronting Young when his spikes slipped on the concrete—and that it was Young who actually lunged at and landed on top of him.44 Seven witnesses testified for the defense, including Gabby Hartnett, each of whom corroborated Wilson’s version of events.

The trial lasted five hours and a courtroom packed with baseball fans heard Wilson portrayed alternately as a “240-pound wild animal charging into baseball boxes” and as a “peace loving citizen.”45 It took the jury just 25 minutes to side with Wilson.46 If the Young case had weighed on Wilson at all, he was now free to embark on the most amazing season he would ever have.

TOP OF THE WORLD

Hack Wilson put together a season for the ages in 1930. With 56 home runs, he set a National League record that would stand for 68 years. He was the second player ever to hit more than 50 in a season, after Babe Ruth. Wilson slashed .356/.454/.723 and led the NL with 105 walks. He is probably best remembered, however, for knocking in 191 runs, a major league record that still stands today—and may never be broken.

If a National League MVP Award had been presented in 1930, Wilson would have won. The same committee of the Baseball Writers’ Association of America that bestowed NL MVP honors on Wilson’s teammate Rogers Hornsby in 1929 conducted a vote following the 1930 season. Hack Wilson edged out Cardinals second baseman Frankie Frisch by six votes, 70-64.47 Unfortunately for Wilson, the NL had abandoned the award (and the $1000 prize) following the vote in 1929 so his win is not officially recognized.48

PERSONA NON GRATA

In spring training in 1931, Cubs player-manager Rogers Hornsby announced Wilson would be moved from center field (the only position he had ever played as a Cub) to right field so that Kiki Cuyler could play center. The NL also introduced a new ball with raised stitches and a thicker cover, hoping to shift some balance back to the pitchers.49

Whether his fall from grace for the Cubs in 1931 (.261/.362/.435, 13 home runs) resulted from being forced to change positions, the new baseball, nighttime galivanting, or some combination thereof, Wilson thoroughly destroyed the goodwill he had earned as a Cub from 1926 through his triumphant 1930 season. In those five seasons, Wilson led the NL in home runs four times, runs batted in twice, and walks twice. His 1.177 OPS in 1930 is still a Cubs record.

On September 1, 1931, club owner William Wrigley Jr. declared, “I hope Hack Wilson is not in a Cub uniform next year.”50 That same day, it was revealed the Phillies had spurned an offer of “$150,000, Hack Wilson, and two other players” in exchange for Chuck Klein.51 Days later, reports surfaced that the Cubs had offered to trade Wilson to the American Association Milwaukee Brewers—for Art Shires—but were rejected.52

The Cubs had hired private detectives to tail Wilson (and pitcher Pat Malone) to verify whether they were complying with curfew rules. The pair was caught breaking training on September 3 in Cincinnati. The next day, Hornsby started pitcher Bud Teachout in right field instead of Wilson.

Before the team returned from Cincinnati to Chicago on September 5, Hornsby instructed Wilson to report to Veeck the next morning, but would not tell him why.53 While at the train station that same night, Malone got into a fight with a pair of mouthy reporters in Wilson’s presence. Apparently, tensions were so high Hornsby would not disembark the train once back in Chicago until provided with a “special bodyguard.”54

On September 6, Cubs management presented Wilson with evidence of numerous curfew infractions dating back to spring training, and then—ironically— condemned him for not getting involved the Malone fight. Wilson was suspended without pay for the remainder of the season. For his “disorderly conduct and roistering,” aggressor Malone was fined, but not suspended.55

Wilson was nonplussed, “All I know is that when I did something wrong when Joe McCarthy was manager of the team, he told me to cut it out, and when I did anything wrong this year, Hornsby told me to report to the front office and they always plastered a big fine on me.”56 Unceremoniously, Hack’s Cubs career was over.

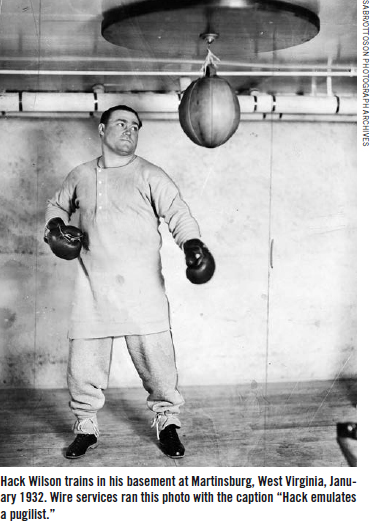

FIGHTING FOR HIS CAREER

Motivated to prove he was still a valuable slugger, Wilson trained in his Martinsburg, West Virginia, basement prior to the 1932. It worked: Wilson had a resurgent 1932 season as the starting right fielder for the Brooklyn Dodgers, slashing .297/.366/.538 with 23 home runs and 123 RBIs. Sadly, 1932 would be his last truly productive major league season.

Wilson’s final start in a big-league uniform came as a member of the Phillies at Wrigley Field on August 18, 1934. He struck out twice and grounded into a double play in three at-bats off his old pal Pat Malone. When asked in 1938 if he would have done anything differently if given an opportunity to do all over, Wilson replied, “I wouldn’t change one minute of it—not a single minute.”57

JOHN RACANELLI is a Chicago lawyer with an insatiable interest in baseball-related litigation. When not rooting for his beloved Cubs (or working), he is probably reading a baseball book or blog, planning his next baseball trip, or enjoying downtime with his wife and family. He is probably the world’s foremost photographer of triple peanuts found at ballgames and likes to think he has one of the most complete collections of vintage handheld electronic baseball games known to exist. John is a member of the Emil Rothe (Chicago) SABR Chapter, founder and Co-Chair of the SABR Baseball Landmarks Research Committee, and a regular contributor to the SABR Baseball Cards Research Committee blog.

Notes

1. Edward Burns, “Who Are These Cubs?,” Omaha World-Herald, September 19, 1929. (The first of the “fistic encounters” recounted by Burns involved Wilson’s arrest on May 23, 1926, at a Chicago speakeasy where Wilson challenged the arresting officers and claimed he was present simply to sign autographs. Others reported Wilson was nabbed trying to climb out a back window and that the tip for the raid actually came from Cubs management. Wilson was arraigned on a charge of disorderly conduct and ordered to buy a $1 charity tag as punishment.)

2. “Even in Death, Hack’s Record Grows,” The (Moline) Dispatch, June 23, 1999. Wilson’s RBI total was reported as 190 throughout his lifetime, until it was officially changed to 191 in 1999.

3. Bud Teachout pitched a single inning for St. Louis in 1932. Hack Wilson hit his first career major league home run off Burleigh Grimes on June 25, 1924.

4. “Wilson Refuses Cards’ $7500 Contract,” Chicago Tribune, January 9, 1932. (Wilson’s 1931 salary with the Cubs was $33,000. Cardinals general manager Branch Rickey offered $7500.)

5. Edward Burns, “Hack Wilson Attacks Fan as Cubs and Cards Divide,” Chicago Tribune, June 22, 1928.

6. Burns.

7. Burns.

8. “Sues Slugger for Slugging Him,” Belvidere (Illinois) Daily Republican, July 25, 1928.

9. “Chicago Fan Loses Razzberry Rights,” Reading (Pennsylvania) Times, June 25, 1928.

10. Edward Young v. Chicago National League Ball Club, Case No. 481272, Complaint, Cook County Superior Court, 1928.

11. https://www.usinflationcalculator.com used for all such calculations throughout.

12. Clifton Blue Parker, Fouled Away (Jefferson, North Carolina: McFarland & Company, Inc., 2000), 74. (Wilson was born to unmarried parents.)

13. “Hack Wilson as Pugilist Has Big Day,” Chicago Tribune, July 5, 1929.

14. “First Tilt,” Cincinnati Enquirer, July 5, 1929.

15. “Hack Wilson as Pugilist Has Big Day,” Chicago Tribune, July 5, 1929.

16. Irving Vaughan, “Warns Reds He’s Set to Fight Again,” Chicago Tribune, July 6, 1929.

17. Vaughan.

18. “Hack Wilson Adds Two Fights to List,” Alton (Illinois) Evening Telegraph, July 5, 1929.

19. “Hack Wilson Anxious for Return Bout,” Omaha World-Herald, July 6, 1929.

20. “Cubs Will Back Hack Wilson,” Wilkes-Barre (Pennsylvania) Record, July 6, 1929.

21. “Hack Wilson Adds Two Fights to List,” Alton (Illinois) Evening Telegraph, July 5, 1929.

22. Edward Young v. Chicago National League Ball Club, Amended Declaration, 1929. (No explanation for dismissing the Chicago National League Ball Club was given.)

23. Edward Young v. Chicago National League Ball Club, Plea of General Issue, 1929.

24. William Weekes, “Cub Outfielder to Get $10,000 for Short Bout,” The (Moline) Dispatch, December 14, 1929.

25. William Weekes, “Great Shires to Meet Sunny Boy Wilson in Arena,” Freeport (Illinois) Journal-Standard, December 14, 1929.

26. On May 15, 1929, Shires and Blackburne faced off in the White Sox clubhouse because Shires got lippy after being told he should not have donned a fashionable “red felt cap” during pre-game batting practice. Irving Vaughan, “Fight Follows Suspension of White Sox Star,” Chicago Tribune, May 16, 1929. The pair came to blows again following a White Sox loss in Philadelphia on September 13, 1929 when Shires “almost chewed [White Sox] Traveling Secretary Lou Barbour’s finger off and blackened manager Lena Blackburne’s eyes” in an altercation in Shires’ hotel room. “Police Called When Sox Star Runs Amuck,” Chicago Tribune, September 14, 1929.

27. William Weekes, “Great Shires to Meet Sunny Boy Wilson in Arena,” Freeport (Illinois) Journal-Standard, December 14, 1929.

28. “Baseball Star Now Under Ban in All States,” Detroit Free Press, January 8, 1930.

29. William Weekes, “Hack Wilson is Signed for Four-Round Match with the Great Shires,” Chippewa Herald-Telegram (Chippewa Falls, Wisconsin), December 14, 1929.

30. Tom Swope, “Kolp Ready to Fight ‘Em All,” Cincinnati Post, December 17, 1929. (In 71 career plate appearances, Wilson hit .259/.394/.500 against Kolp, with 13 walks and 4 home runs.)

31. “Hack Wilson Will Not Fight Shires,” Sterling (Illinois) Dally Gazette, December 17, 1929.

32. “First Baseman Signs to Box ‘Hack’ Wilson,” Tampa Times, December 14, 1929.

33. “Shires May Engage in One More Fight,” Rock Island (Illinois) Argus, January 11, 1930.

34. “Wilson Aroused Seeking Permit to Fight Shires,” Freeport (Illinois) Journal-Standard, January 13, 1930.

35. “Hack Aroused by Shires’ Remarks,” The (Moline) Dispatch, January 13, 1930.

36. Davis Walsh, “Clubs Aim to Stop Players from Boxing,” The (Streator, Illinois) Times, January 14, 1930.

37. “Landis and Shires,” Collyer’s Eye (Chicago, Illinois) January 25, 1930.

38. “‘Hack’ Wilson Faces Court Case Today in Chicago,” Pittsburgh Press, February 11, 1930.

39. “Tells Jury of Hack Wilson’s Attack on Him,” Belvidere (Illinois) Daily Republican, February 11, 1930.

40. “$20,000 Claim Filed by Bruin Fan Dismissed,” The (Moline, Illinois) Dispatch, February 12, 1930.

41. Irving Vaughan, “Jury Unmoved by Milkman’s Story of Fight,” Chicago Tribune, February 12, 1930.

42. Paul Mickelson, “Wilson is Cleared on Assault Charge,” Nebraska State Journal (Lincoln, Nebraska) February 12, 1930.

43. “$20,000 Claim Filed by Bruin Fan Dismissed,” The (Moline, Illinois) Dispatch, February 12, 1930.

44. Irving Vaughan, “Jury Unmoved by Milkman’s Story of Fight,” Chicago Tribune, February 12, 1930.

45. Paul Mickelson, “Wilson is Cleared on Assault Charge,” Nebraska State Journal (Lincoln, Nebraska) February 12, 1930. (After the verdict was entered, Wilson quipped, “The only crack I didn’t like was that about being a 240-pound wild animal, if the Cubs think I weigh 240 pounds, they will make me carry bats.”)

46. “Hack Wilson Given Verdict in Damage Suit with Milkman,” Corsicana (Texas) Daily Sun, February 12, 1930.

47. “1930 Home Run King is Voted ‘Most Valuable’,” Messenger-Inquirer (Owensboro, Kentucky) October 8, 1930.

48. “Hack Wilson Will Get $1000 Just the Same,” Boston Globe, October 8, 1930. (The Cubs voluntarily agreed to pay Wilson the $1000 prize he would have received if the award was still official.)

49. Orlo Robertson, “New Ball Fails to Scare Babe and Hack,” The (Belleville, Illinois) Daily Advocate, February 10, 1931. (In 1930 the National League collectively hit .303/.360/.448 with 892 home runs, after the introduction of the new ball the league hit .277/.334/.387 with 493 home runs in 1931.)

50. “‘Hack’ Wilson is No Longer Wanted on Club,” The (Woodstock, Illinois) Daily Sentinel, September 1, 1931.

51. “Phillies Refuse Cubs’ $150,000 Offer for Klein,” Chicago Tribune, September 1, 1931. (Wrigley’s wish came true posthumously when the Cubs acquired Klein via trade with the Phillies on November 21, 1933 in exchange for Harvey Hendrick, Ted Kleinhans, Mark Koenig, and $65,000.)

52. George Kirksey, “Hack Dropped Without Pay by Hornsby,” Minneapolis Star, September 7, 1931. (Shires ended the 1931 season with a .385 batting average for the AA Brewers.)

53. Frank Klein, “Demand Veeck and Hornsby be Removed,” Collyer’s Eye and The Baseball World, September 12, 1931.

54. Klein.

55. George Kirksey, “Hack Dropped Without Pay by Hornsby,” Minneapolis Star, September 7, 1931.

56. George Kirksey, “Hack Wilson Returns to His West Virginia Home,” Decatur Daily Review, September 11, 1931.

57. Bob Considine, “Old Times,” Cincinnati Enquirer, October 26, 1938.