Harry & Larry

This article was written by Matthew Clifford

This article was published in Fall 2015 Baseball Research Journal

Sometimes research leads us to answers we never intended to find. My quest began in 2010 when I set out to review the history of an unlucky baseball pitcher named Sylvester “Syl” Johnson. This man had the honor to work with one of the most notorious baseball men in history, Tyrus Raymond Cobb. He was also hit by nine line drives off his own pitches, all of which led to broken bones. Sylvester joined the Detroit Tigers in 1922 and stayed until 1925. During those four years, he worked with a catcher named Charles Lawrence “Larry” Woodall. Johnson also shared the field with Detroit’s powerhitting right fielder, Harry Edwin “Slug” Heilmann.

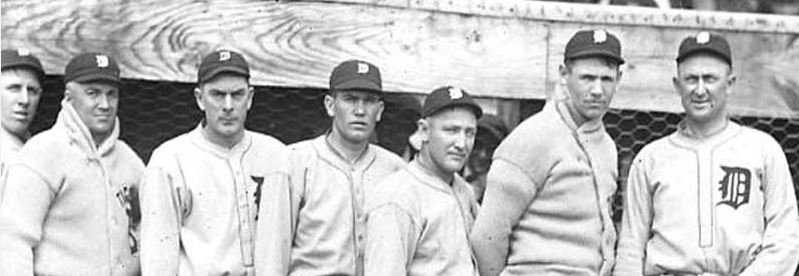

1923 Detroit Tigers. Standing left to right: Bob Fothergill, Johnny Bassler, Bobby Veach, Larry Woodall, Fred Haney, Harry Heilmann, Ty Cobb.

In 2011, I found a black and white photograph taken in 1923. The picture included six members of the Detroit Tigers standing in front of a dugout with their temperamental skipper, Mr. Cobb. This pesky photo led me into a journey that would permanently affect my cross-reference methods. I had reviewed hundreds of pictures of the 1922 Tigers, the year Johnson began his major league career.

In a 1923 photo, the first fellow I spotted on the left was Bob “Fatty” Fothergill. Bob, a relief outfielder, was also signed in 1922 and I had previously examined several images from his rookie year. Don’t assume that his nickname “Fatty” assisted my identification. The hefty gentleman’s figure was not visible—the edge of the photograph trimmed at his neck. Fothergill’s tired-eyed stare was the first feature I recognized. But, just to be sure, I cross-referenced the photo with Bob’s picture on his profile page at Baseball-Reference.com. His wearyeyed glance stared back at me, verifying my guess.

The man standing to Fothergill’s right was catcher Johnny Bassler. The only man smarter than the weather in the picture, Bassler wore a wool cardigan sweater with a calligraphy “D” on his chest. Johnny had facial features that were simple to remember. Baseball-Reference confirmed my memory.

The third man in the row was another no-brainer. The angry gape of Bobby Veach had frightened me when I initially started my research of the Tigers from the 1920s. Bobby’s face was occupied by a pair of sharp and icy eyebrows that would make any player second guess themselves before confronting him. On reviewing his career, I learned that his menacing eyebrows did not match his upbeat demeanor. I read one story that Cobb had purposely instructed a player to taunt Veach when he stepped into the batter’s box. Veach, known to have a friendly conversation with the opposing team’s catcher before the pitch crossed the plate, had infuriated Cobb (who was not one to extend any courtesy to his opponents).

Veach occupied Detroit’s left field from 1912 until 1923. This photograph captured one of the last days of Veach dressed in Detroit duds. The man standing to the right of Bobby Veach was a gentlemen who stuck out in more ways than one. Larry Woodall was born with the physical feature of ears that I would classify as “cab doors,” like a small fan on both sides of his face.

The fifth man in the lineup was another 1922 rookie named Fred Haney. I noted Haney as the only third baseman and the shortest man in the picture. Just shy of five-foot-six, Fred’s identity was confirmed by Baseball-Reference.com. I ran into a problem when I came to the sixth man in the lineup. Towering over Haney by seven inches stood Harry Heilmann. I recalled other photos I had seen of this legendary hitter. He reminded me of today’s popular actor Russell Crowe. Crowe, known for his roles as James J. Braddock in the 2005 motion picture, Cinderella Man, and Maximus Meridius in the 2000 film, Gladiator, could have been Harry Heilmann’s relative.

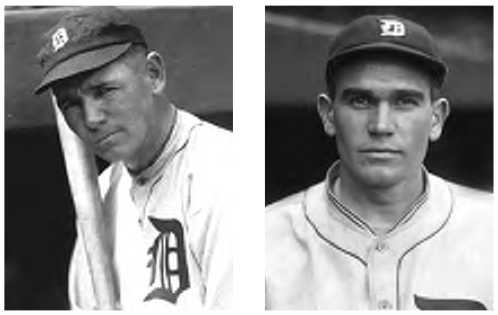

Harry Heilmann (left) and Larry Woodall (right)

Worried that my interest in modern films might cloud my research judgment, I went to Baseball-Reference.com to compare Harry’s profile picture with the 1923 photo. I found Harry’s page but Harry wasn’t there. His full name and every accurate stat of his career were there. But rather than finding my expected look-a-like shot of Russell Crowe, I found a snapshot of Woodall and his cab door ears! Why was Larry on Harry’s page?

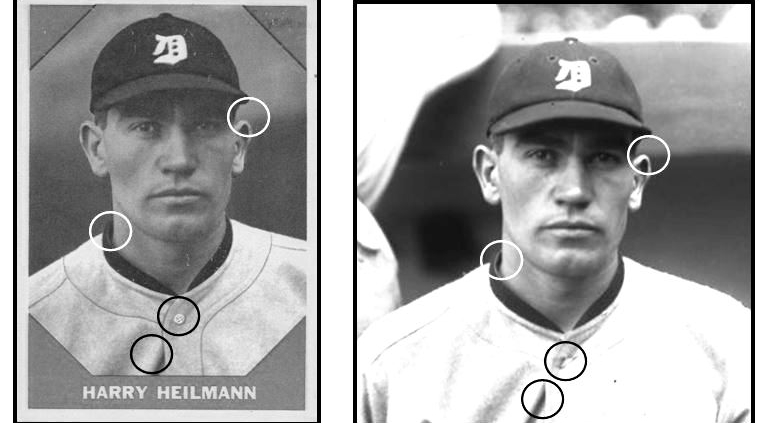

I went back to Woodall’s profile page on Baseball-Reference.com. Larry was there, accurately where he belonged. After clicking back and forth between Heilmann and Woodall, I determined two differences. On Larry’s page, his photo showed his eyes looking up. On Harry’s page, Larry’s photo showed his eyes looking right at the camera. Then I saw something else. Larry’s picture on Harry’s page was a face shot, just like the other one—but there was a distinctive white space in the upper left-hand corner of the picture. I surfed the web to collect additional pictures of both players. My opinion that Heilmann and Crowe shared similar facial features was verified. Woodall and his protruding cab doors were also verified. Then I stumbled across a baseball card printed in 1960 that made my jaw drop.

Card #65 “Harry Heilmann” from Fleer’s 1960 Baseball Greats card set.

Card #65 from the 1960 Fleer set titled “Baseball Greats” was marked “Harry Heilman.” But Heilmann’s face was not on the face of the card—it was Larry Woodall in the same pose as appeared on his Baseball-Reference page. I purchased Card #65 from an online auction. Both the front and back of the card read “Harry Heilman.” Harry’s stats were printed on the backside but Woodall’s face was undoubtedtly affixed to the front.

Fleer had colorized the original 1923 Woodall photo by adding ink blasts of pink skin tone and blots of navy blue to enhance his Detroit ball cap. Below the modernized reproduction in bold, white print, read two words: “Harry Heilmann.” Wow.

My first step to correct the error was to notify the National Baseball Hall of Fame and Museum in Cooperstown, New York. I traded letters with a brilliant and helpful gentleman named Freddy Berowski. Freddy agreed with my findings and thanked me for my “keen eye for detail” along with his surprise that Card #65 had gone unnoticed for so many years.

I then contacted the web team at Baseball-Reference.com, pointing out the error, and suggesting that Harry’s Card #65 may have led the creators of Heilmann’s profile page in the wrong direction. Baseball-Reference.com immediately responded, and replaced Harry’s photo with an accurate one in July 2011.

I continued to review more photos of Harry and Larry before I contacted the Fleer Corporation. The powerhouse sports card company, founded in 1885, had been sold in 1992 to the Marvel comic book company, then to a private company, then to Upper Deck after it was declared bankrupt. As I researched Upper Deck, I found another error!

Card #DC-HC “Cobb/Heilmann” from Upper Deck’s 2005 Legendary Cuts “Dual Cuts.”

In 2001, Upper Deck had released a new baseball card series titled “Legendary Cuts.” These expensive, limited number sets featured hand cut signatures of legendary baseball players. Some sets included players’ signatures with authentic pieces of the player’s bats and uniform swatches. Others included photographs of the players set next to their genuine autographs. Upper Deck continues to issue these sets today. In 2005, Upper Deck added a dual signature card to their Legendary Cuts set. One card was titled “DC-HC,” and featured two of Detroit’s most renowned baseball legends, Ty Cobb and Harry Heilmann. Named “DC” for “Dual Cuts” and “HC” for “Heilmann/Cobb,” the card was hand numbered “1/1,” signifying that only one card (featuring the signatures of Cobb and Heilmann) existed in the set. But there was a problem.

I found no fault with the lower half of the card displaying an accurate photo of Tyrus Cobb and the original cursive of his authentic autograph. But the upper half of the card displayed Heilmann’s valid signature set next to a small, sepia and black colorized photo of Charles Lawrence “Larry” Woodall! When I found the card on an online auction website priced for $5,995, I contacted the seller about the error and the card disappeared from the Internet. I had learned long ago that error cards are worth more than their “corrected” cards. I felt as if I had tiptoed past a cat that got spooked and ran away. (On March 14, 2012, the Upper Deck Card DC-HC sold for a final private bid of $1,558.)

Card #9 “Harry Heilmann” from Panini’s 2012 National Treasures “League Leaders”

Meanwhile, I traded emails with Lyman Hardeman, the editor of the popular baseball card website “Old Cardboard.” He agreed with my observation of Fleer Card #65. More interest followed after I contacted Rich Mueller, editor of the “Sports Collector Daily” website. In late July 2011, both sites graced me with digital ink as they presented details of my detection, which was cleverly coined “The Mix-Up of Harry & Larry.” My Internet news story earned more interest a few weeks later. During my photograph review, I noticed that another baseball card company had committed several new errors. Panini America Incorporated has been in the business of sports collectibles and cards for years. In 2012, not long after my confusion between Harry & Larry was beginning to calm, Panini released their “National Treasures” baseball card series. These cards included old and recent baseball players’ autographs, personal uniform swatches, and authentic baseball bat chips. Card #9 from Panini’s 2012 National Treasures “League Leaders” set of 99 cards was titled, “Harry Heilmann” and wouldn’t you know it, Harry’s mug was missing from the face of the card, replaced by Larry’s.

Card #5 “Collins/Gehrig/Heilmann/Kamm” from Panini’s 2012 National Treasures “All Decade Quad.”

When Panini manufactured other categories titled “Legends” and “All-Decade,” Heilmann’s name and bat chips continued to be accompanied by Woodall’s image, although some Heilmann cards from the “Legends” and “All Decade” categories were printed with accurate photos of Harry and some of Larry. Altogether, of the 488 Harry Heilmann cards issued by Panini in their 2012 National Treasures set, 334 had accurate photos of Harry and 154 had pictures of Larry. I attempted to contact the Upper Deck Company and Panini America Inc. by email and snail mail in 2012, but I have not received a reply to date.

Many of the Heilmann error cards from Panini’s “National Treasures” that I had discovered and noted have been graded, authenticated, and inspected by trusted sports card grading companies. It’s amazing that two men (who look nothing alike) were confused and permanently printed, graded, and sealed in the history annals of error cards. Then I found another problem that deserved some attention.

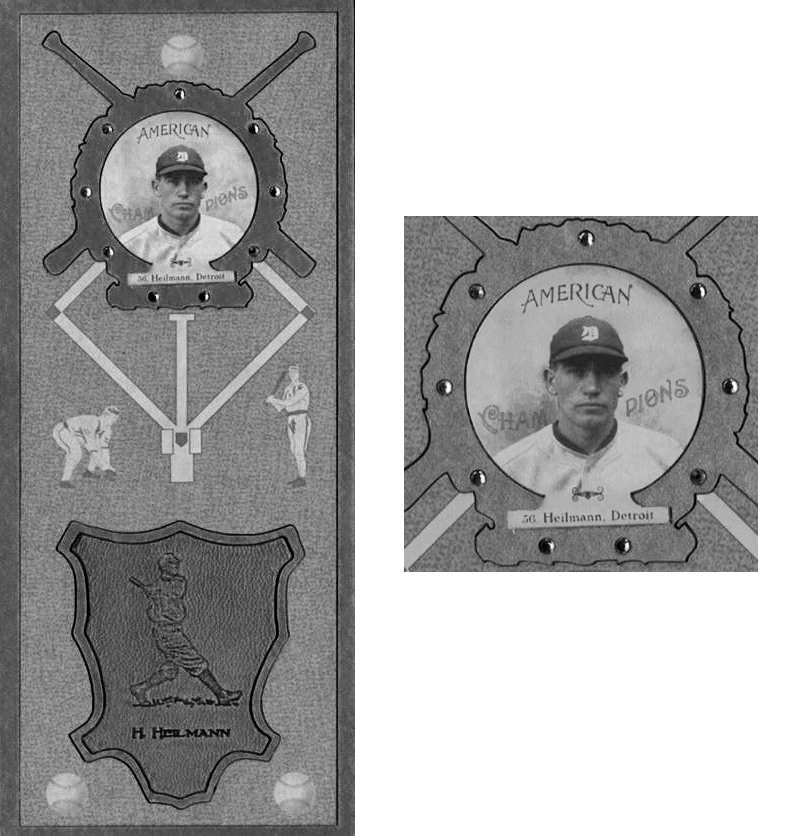

2012 Helmar Brewing L# Cabinet Card #56: full view and close-up.

The Helmar Brewing Company, a prosperous beer franchise located in Detroit, released a set of “cabinet cards” in 2012. The owner of the company, Charles Mandel, created a successful brewing company and followed his personal passion to create old-time sports cards for today’s modern collector. Helmar cards have a unique appearance and feel in comparison to the fresh, sharp-edged cards of new players. These new “old-time” cards are purposely discolored, scraped and weathered to create an aged look. The company releases cards of old-time players like Mel Ott, Ty Cobb, and—you guessed it—Harry Heilmann.

Mandel’s company created cabinet cards, otherwise noted as “L3” cards. There are 207 cards measuring 9.5 inches tall and 4 inches wide in the 2012 set. Each features a separate player. Brilliant color and added details of branded leather and nine chips of Swarovski crystal cover the face of the card, above and below the player’s photograph. The L3 card set is amazing… and so is Card #56. I examined this card and noticed Heilmann’s name burned in the leather. Harry’s name, along with the names of 204 star players from the Detroit Tigers are listed on the back side of the card. On the face of the card, surrounded by nine sparkling crystals, is the face of a catcher who never made any prominent records in the Detroit annals. It was a face I clearly recognized. Larry Woodall was staring back at me again.

I contacted the Helmar Brewing Company in 2013 and traded emails with Charles Mandel, who apologized for creating the Heilmann error card. I purchased the card happily and added it to the other Heilmann error cards I had been collecting for the past two years. Not long after I made contact with Mr. Mandel, I received an email from Bill Wagner. Known professionally as “Da Babe” or “Babe Waxpak,” Wagner was a writer for the Scripps Howard News Service. Recognized for his writing talent and advice and enthusiasm as a sports card collector, Wagner inquired into the details behind “The Mix-Up of Harry & Larry.”

After an interesting conversation, I was honored to work with the talented gentleman shortly before he announced his retirement. In late October 2013, the details of my discovery made press ink. Bill Wagner titled the story, “Error Corrected After 90 Years.” By now I felt passionate about finding the origin of this error that had produced hundreds of cards confusing these two players since Fleer committed the initial error in 1960.

The first step of my investigation was to closely examine the details of the Woodall image used on Baseball-Reference.com and the cards issued by Fleer, Upper Deck, Panini, and Helmar. Every photo was an identical match. Each company changed the color of the image, but the shadows and physical image of Woodall remained the same, altered to conform to the setup and background of each company’s design. Some companies took a “block shot” of the Woodall image, cut from the original photograph with four edges of the original background that surrounded Larry when the shot was taken.

Other companies cropped Woodall’s image as they cut away the original background that surrounded Larry. These cut images were trimmed closely against Woodall’s face, cap, uniform and shoulders. I wanted to know the details of the “white void” I noticed in the image on Heilmann’s profile page on BaseballReference.com. I started a relentless search for the original image. I contacted libraries in Detroit and requested a search of images of Charles Woodall, Larry Woodall, and Harry Heilmann.

My digging paid off when one of my late night Internet image searches hit. ESPN.com had created a webpage on December 12, 2012, titled, “Hall of 100—Ranking All-Time Greatest MLB Players.” I found the original photo of Larry Woodall incorrectly included on Harry Heilmann’s ESPN.com webpage on which Harry was ranked as #110 in the “Honorable Mention” category. Similar to Baseball-Reference.com’s stats and details, Heilmann’s notations were correctly displayed with the wrong player’s photograph.

I took a digital snapshot of the photo used by ESPN.com and enlarged it. I immediately spotted the reason for the “white void” I had seen. It was another player’s elbow. In the background, facing the opposite direction from Woodall, a player stood on the left side of Larry with his arms and elbows resting on the top of the concrete dugout. Then I took a closer look at Fleer’s Card #65. I could vaguely see the heavily colorized and shaded section occupying the upper left corner of the card, erasing the player’s elbow from the original shot. The edge of the dugout extended from the player’s elbow behind Woodall’s head and reappeared over Larry’s right ear. Fleer could not erase the dugout edge above Larry’s ear.

The photo on ESPN, Baseball-Reference, and Fleer’s card #65 were a match. ESPN’s image added another detail that caught my eye. Their photo included a closer view of the top button of Woodall’s uniform. A metal safety pin was clearly visible, used as a makeshift button. ESPN’s photo was obviously the original photograph, with no alterations. I compared that to Fleer’s card #65, on which Woodall’s top button is fastened and nicely detailed with a round button. Fleer had cleverly drawn a bright, white button over Woodall’s safety pin. Fleer also colorized the black and white photo and attempted to blur the player’s elbow in the upper left corner. A closer look at ESPN.com’s picture revealed that the photograph was credited “AP Photo.”

1923 AP photograph of Lawrence Woodall, the original picture that started the author’s quest.

On September 11, 2013, I searched the Internet and found the website for the Associated Press. I searched through the images and found the “X” on my treasure map. APimages.com had a category titled “Harry Heilmann.” I clicked on Heilmann’s link and found three “Heilmann” photos. One was a 2010 photograph of Harry P. Heilmann, the assistant Chief Engineer of the Washington Metropolitan Area Transit Authority. Since my research didn’t involve Washington trains, I skipped over the details of this “Heilmann.” One, copyright number 2601010370, dated 1/1/1926 was an accurate image of the Tigers’ Harry Heilmann, kneeling with one knee down while holding himself up with a bat. The third, dated 1/1/1923, was really Charles Lawrence “Larry” Woodall, a silver pin clasped under his Adam’s apple and a clearly visible player facing away from him with relaxed elbows on top of a dugout.1 It was a great sight to see: the original photograph. It was labeled copyright number 2601010266. My eyes focused to the lower right of the photo as I examined the original chalk used to number it. I noted the handwritten digits “16” in white grease pencil on the black and white photo. Considering that this original photo could be in reverse (as many pictures are), I concluded that this number could be “91” if the photo negative was upside down.

I had found what I had been looking for and I was thrilled.

1960 Fleer’s Baseball Greats Card #65 Photo / 1923 Original Photo of Larry Woodall (Comparison Circles: “Dugout/Ear,” “Void/Collar,” “Pin/Button,” “Fold/Chest”).

I printed the picture and drew horizontal and vertical lines over it to create a grid. I did the same with Fleer’s card #65, Upper Deck’s DC-HC, the Panini’s cards, Helmar’s card #56 and Baseball-Reference’s erroneous photo. I was able to confirm that every photo included a dark shadow “void” on the left side of Larry’s neck. This helped me to verify that all pictures were an identical match to the chalk-marked original AP photograph. Could there be a chance that AP had the original physical photograph in their archives? If they did, was it likely that the back of the photo was incorrectly labeled “Harry” instead of “Larry”? I considered the possibility that the artist responsible for taking the snapshot was the famous baseball shutterbug, Charles M. Conlon.

Conlon was known to take snapshots of players as they stood alone in a dugout. I quickly reviewed and eliminated Conlon’s competitor, Chicago sports photographer George Brace, since Brace did not begin taking baseball photos until 1929. If this was an authentic Conlon shot, why was it owned by the Associated Press? I contacted the AP and requested a copy of the picture. My offer was rejected by the AP’s contracted sales company, Replay Photos, who explained, “AP does not have the rights to sell this photo for personal use. Unfortunately Major League Baseball prevents us from having the rights to sell prints of Major League Baseball players, even for personal use.” MLB owns the photos and allows AP the rights to license and distribute them to professional publishing companies. I asked Replay Photos to inspect the original photograph and check the blank reverse side for the names Larry and Woodall, explaining in tedious detail the errors I had found. Sadly, I never received a reply. In October 2013, Bill “Waxpak” Wagner contacted Associated Press and spoke with Paul Colford, AP’s Director of Media Relations, to discuss the details of my error discovery. Colford advised Wagner, “We’re unable, so many years later, to determine how the image came to be misidentified initially. However, it is properly identified now, so that any future licensor of the photo from AP images can be confident.”2 Wagner’s interview with AP and the specifics of the errors I discovered were added to Wagner’s story: “Error Corrected After 90 Years.” I believe it’s possible that when Larry’s original shot was taken, it was marked incorrectly with the name “Harry,” and that started it all.

Both players were with the Tigers from 1920 through 1929. They were born eight days apart in 1894. Harry was elected to the National Baseball Hall of Fame in 1952. A year before he was given his baseball honor, Harry “Slug” Heilmann died in Southfield, Michigan, on July 9, 1951. Woodall passed away twelve years later on May 6, 1963, in Cambridge, Massachusetts.

Heilmann lived up to his handle, “Slug,” collecting 2,660 hits during his 17-year career in the major leagues. In 1923 Harry earned an astounding .4027 batting average. Larry gathered 353 hits during his decade with Detroit. Although he never made the history books for anything outstanding during his time on the major league fields, Larry Woodall’s face landed on popular baseball cards linking him with Harry Heilmann’s statistics, Heilmann’s name, and Heilmann’s honors.

When I initially discovered the error, I couldn’t help but imagine two photograph artists yelling back and forth to each other in a loud printing press office at the Fleer headquarters. Perhaps when the design of card #65 was in the process of production, one artist yelled “Harry” across the room to his co-worker—when he should have yelled “Larry.” Maybe the back of the original Woodall photograph negative has the incorrect label. No matter what the truth is, the error carried on for almost 100 years and I was more than happy to be a part of its history.

MATTHEW M. CLIFFORD is a freelance writer from the suburbs of Chicago. He joined SABR in 2011 with intentions to enhance his research abilities and literary talents to help preserve accurate facts of baseball history. Clifford has a background in law enforcement and is certified in a variety of forensic investigative techniques, all of which currently aid him with historical research and data collection. He has recorded and reported several baseball card errors and inaccuracies of player history to SABR and the research department of the National Baseball Hall of Fame. Clifford has published in the SABR Biography Project and “The National Pastime.”

Notes

1 EDITOR’S NOTE: It is common practice for the AP and other historical photo collections to use “January 1” as a generic date indicating the year of the photo is known, but the exact day is not.

2 “Babe Waxpak/Sports Collectibles: Error Corrected After 90 Years,” Indiana Gazette, October 19, 2013.