Harvard Boy Revisited: When Rick Wolff Chronicled the Minors

This article was written by John Fredland

This article was published in The National Pastime: Major Research on the Minor Leagues (2022)

In June 1972, the Detroit Tigers selected Harvard University’s Rick Wolff in the 33rd round of baseball’s amateur draft.1 Wolff played two seasons in Detroit’s farm system, batting .236 in 196 Class A games before retiring to attend law school, and then pursue careers in publishing and sports psychology.

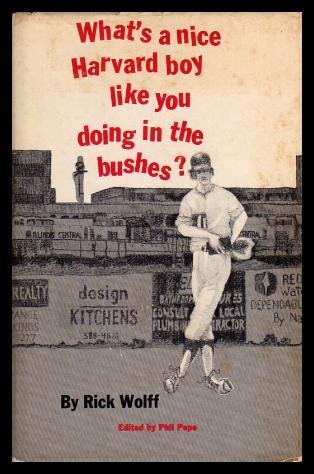

Wolff’s time in the Western Carolinas League and Midwest League also yielded a charming, compelling, and valuable artifact for baseball fans and students of the minors: a book-length, first-person chronicle of his time with the Anderson Tigers and Clinton Tigers. Published in 1975, Wolff’s What’s a Nice Harvard Boy Like You Doing in the Bushes? fits alongside contemporaries like Jim Bouton’s 1970 Ball Four and Sparky Lyle’s 1979 The Bronx Zoo in its depiction of a baseball player’s day-to-day life, and foreshadows Bull Durham’s 1988 cinematic portrayal of life in the minors.2

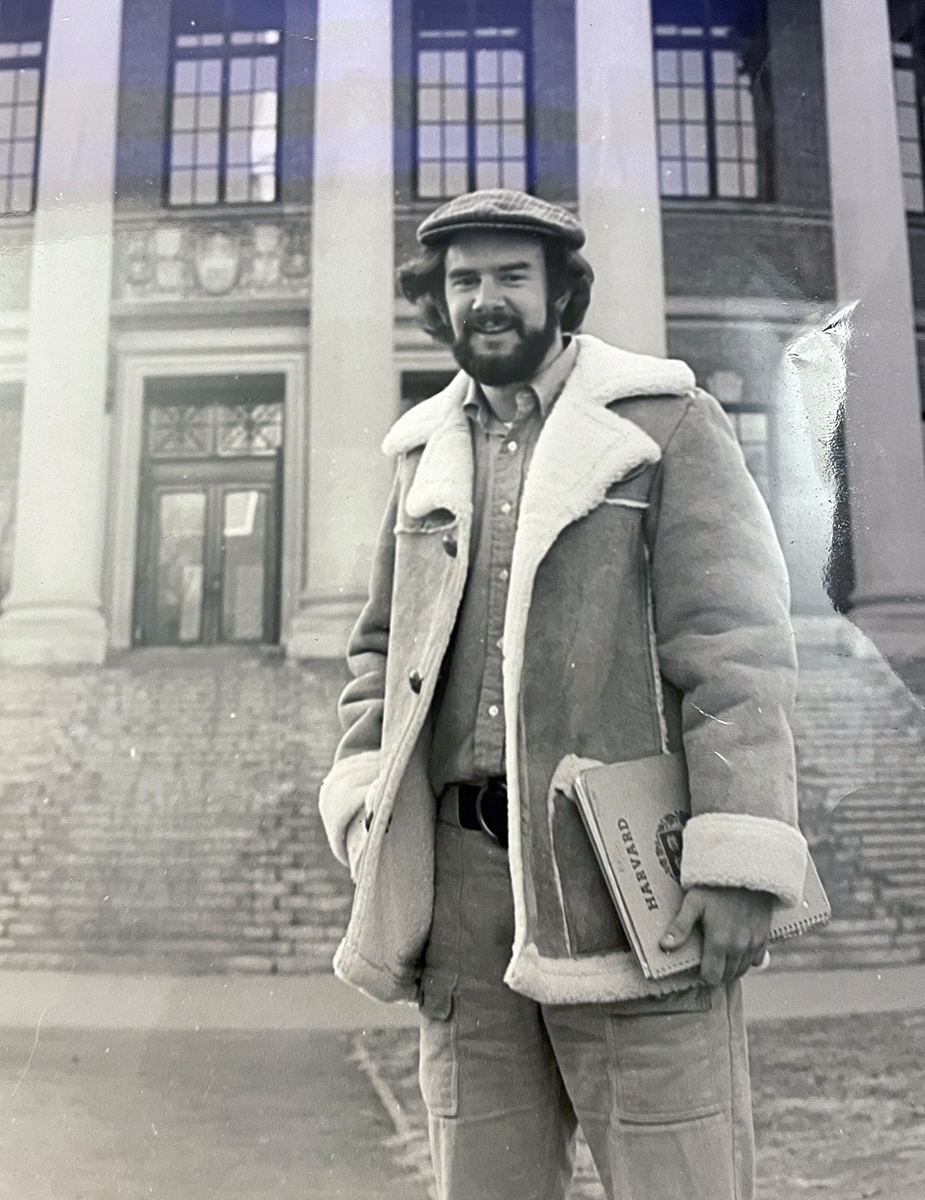

Rick Wolff, shown in this 1973 photo in front of the Widener Library, chronicled his journey from Harvard to the Detroit Tigers’ organization in “What’s A Nice Harvard Boy Like You Doing In The Bushes?” (Photo by Nelson Chen)

Wolff’s book originated from a conversation with New York Daily News sportswriter Phil Pepe after his first season in the minors. Wolff’s father was Bob Wolff, who received the 1995 Ford C. Frick Award for a broadcasting career that included radio and television work for the Washington Nationals/Senators, Minnesota Twins, and national outlets.3 Bob Wolff and Pepe were friends, and Rick Wolff relayed stories of his minor-league experience over dinner at Yankee Stadium.4 Pepe suggested that he write an article for a baseball magazine about it.5

Wolff wrote the article, drawing on letters that he had sent his parents during the season.6

“This was the early ’70s—there was no Internet, no cable TV, no cell phones,” Wolff remembered in a 2022 interview.7 “Once a week, I would call home from a pay phone, because it was too expensive to call home. I got in the habit of writing letters. Every couple of days I’d write a note about what was happening, how I was doing.”8

His article got the attention of a book editor, who recommended that Wolff develop it into a book, which he did, with Pepe’s assistance.9 The result was a candid account of Wolff’s two seasons in Class A ball, albeit without the sensationalism of Ball Four or the raunchiness of The Bronx Zoo.10

“When I was in the minors, the impact of Ball Four was everywhere,” Wolff said.11 “In those days, especially in the minors, it was like being in the military—you just said, ‘yes sir, no sir.’12

“I can very vividly recall my second spring training, when [Detroit’s] director of minor league baseball, an old gruff guy, former major-leaguer named Hoot Evers, walked by me when we were working out,” Wolff remembered.13 “He looked at me and he said, ‘Have you read any good books lately?…Or maybe I should say, Have you written any good books lately?’ With the amount of sarcasm in his voice he was making it clear to me that I had to be very careful about what I put into my book.”14

Wolff drew on a cast of characters—all real people as named15—that included many familiar faces in lesser-known stages of their lives and careers. Mike Hargrove is a near-impossible out for the Gastonia Rangers in 1973, “adjusting [at bat] better than anyone else.”16 A year later Wolff and his teammates would be watching him on the Game of the Week, at the dawn of Hargrove’s three decades as major-league player, coach, and manager.17

Matt Keough is “a fine shortstop, but he’s a slap hitter and not considered a long ball threat” in the Midwest League; Keough soon converted to pitching, resulting in a decade-long career in the majors.18 Hoyt Wilhelm, managing in the Western Carolinas League less than a year after his final game as an active player, tosses his knuckler in batting practice.19 Other names— Moe Hill, Lafayette Currence, Ed Nottle—may resonate with students of the minors.

But Harvard Boy’s true heart beats in its descriptions of a protagonist and his teammates who likewise never reached the majors as players, young men who pursued their dreams through success and failure, joy and pain, and camaraderie and isolation. There’s wisecracking relief pitcher Brian Sheekey, a New Jersey native, “a cocky guy with big city sophistication, an operator who always gets the upper hand,” who provides one of the book’s most poignant scenes when the Tigers cut him during spring training of the book’s second season.20

There’s Ray Gimenez, who steals the show at a team meeting with “the most sincere, most appealing speech I’ve ever heard in a clubhouse.”21 There’s Steve Tissot, a 26-year-old guitar-playing college grad, reading Hermann Hesse and Nietzsche and theorizing on human performance.22

Over a decade before former Baltimore Orioles farmhand Ron Shelton’s Bull Durham screenplay brought the minors to America’s movie screens, Wolff offered similarly mundane, quirky, and poignant vignettes of minor-league life.23 A group of bored ballplayers go to see The Sound of Music.24 The closing line of The Great Gatsby punctuates a mound meeting.25 A Black player has an outstanding game in Greenwood, South Carolina, while the Klu Klux Klan rallies outside the ballpark.26 “Clown Prince of Baseball” Max Patkin appears in Harvard Boy, just as in Bull Durham.27

Harvard Boy ended with a cliffhanger. Wolff has completed his second season in the minors and started law school at Boston College, still hopeful for another year in the pros.28 What happened next was a candid conversation with Hoot Evers, who offered him a contract for 1975, but told Wolff that he would return to Class A and was being groomed as a utility man.29

Wolff elected to retire.30 In 1989, however, 15 years after his final game with the Tigers, he returned to the Midwest League to play three games with the South Bend White Sox for a Sports Illustrated article, batting .571.31

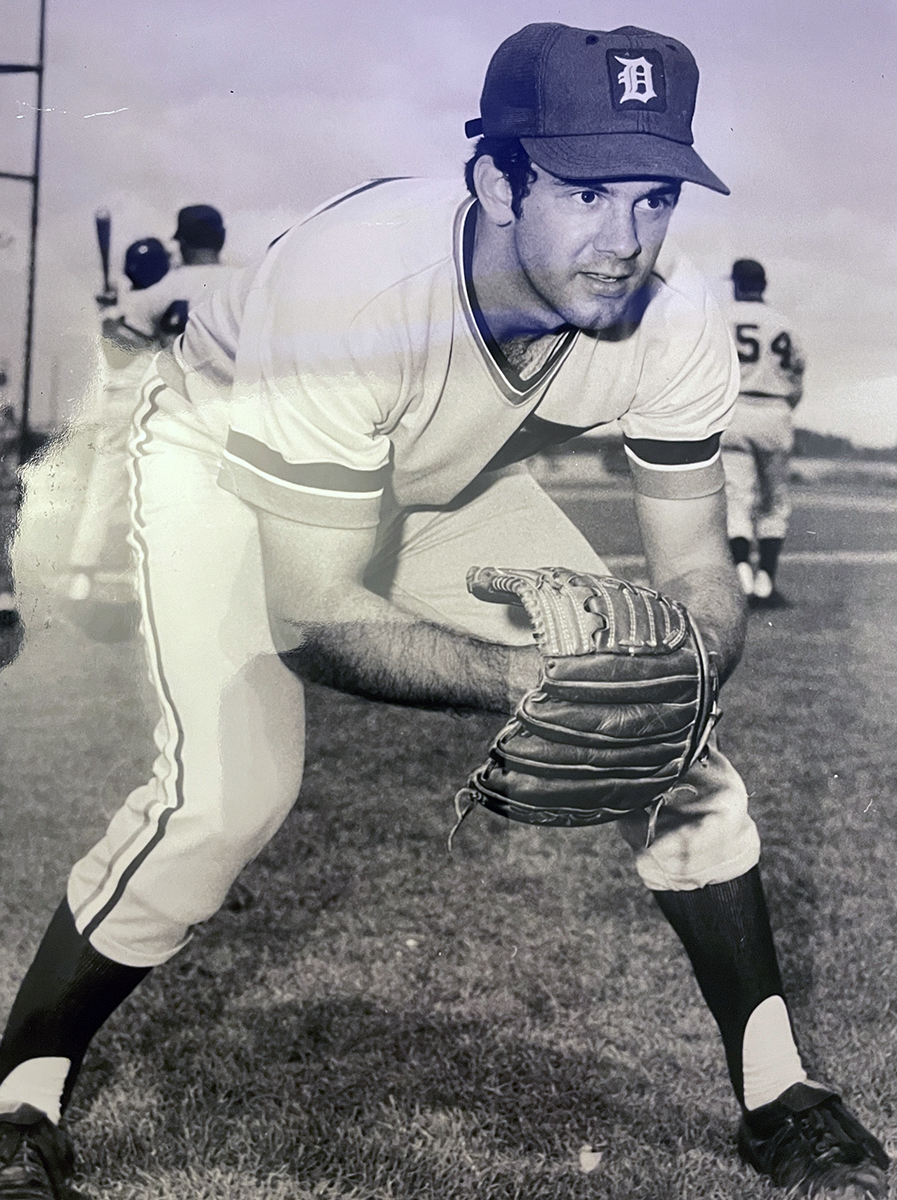

Rick Wolff in his official Tigers team photo. (Courtesy of the Detroit Tigers)

Even though Wolff never reached the majors as a player, writing Harvard Boy led to a career in publishing, with the opportunity to oversee two beloved baseball books. One of the books, coincidentally, was Ball Four itself. In 1989, its original publisher folded and sold off its licensed properties. Wolff, then an editor at Macmillan, persuaded the company to bid for its rights. Once Macmillan had acquired Ball Four, Wolff worked with Bouton on an updated preface and new afterword, which came out in the book’s 1990 update.32

At Macmillan, Wolff also edited three editions of the Baseball Encyclopedia. While ensuring the Encyclopedia’s records were accurate, Wolff worked with several SABR members, including Ken Samuelson.33 “It was a joy to work with these guys from SABR because they had such great knowledge and insight, and they did all the legwork in terms of going out and checking old newspapers and records,” Wolff said.34

Wolff also pursued interests in sports psychology, which caught the attention of prominent baseball psychologist Harvey Dorfman.35 In 1990 he became the Cleveland Indians’ first-ever sports psychology coach—giving him the opportunity to wear a major-league uniform.36 “Harvey said to me, ‘If you’re going to be working with these ballplayers, you have to build a rapport with them,’” Wolff remembered.37 “They should know you know how to act on a ballfield, that you actually played the game and you’re legit.”38

Nearly five decades after Harvard Boy’s publication, Wolff counts his minor-league experience and book among the highlights of his life. “I look back and say, ‘wow—that was amazing. It was just something you did because you had a passion for the sport, and you hoped and prayed that it may take you somewhere in the future.”39

JOHN FREDLAND, an attorney and retired Air Force officer, grew up in a suburb of Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania. As an undergraduate at Rice University, he covered Rice’s nationally ranked baseball teams for the school newspaper, the Rice Thresher. John received his law degree at Vanderbilt University, then served as an active-duty attorney in the Air Force’s Judge Advocate General’s Corps for 20 years. He currently lives in San Antonio, Texas, and chairs SABR’s Games Project. John’s fascination with Rick Wolff’s “What’s A Nice Harvard Boy Like You Doing In The Bushes?” dates to inheriting a copy from his grandfather, a high school baseball coach and true student of the game, at age 12.

Notes

1. A December 1972 Boston Globe article by Peter Gammons facetiously named Wolff “New England Collegiate Sportsman of the Year” for being drafted by the Tigers despite limited playing time at Harvard, including not starting a game in two years. Wolff’s play in the summer Atlantic Collegiate Baseball League, where he ranked among the league leaders in batting average and steals at the time of the draft in June 1972, appears to have been a larger factor in the Tigers’ decision to select him. Peter Gammons, “Rick Wolff…That’s Who Rates Award,” Boston Globe, December 31, 1972: 40; “ACBL Statistics,” Hackensack (New Jersey) Record, June 30, 1972: B-10.

2. Rick Wolff, What’s a Nice Harvard Boy Like You Doing in the Bushes? (Englewood Cliffs: Prentice-Hall, 1975); Jim Bouton, with Leonard Shechter, Ball Four: My Life and Hard Times Throwing the Knuckleball in the Big Leagues (New York: The World Publishing, 1970); Sparky Lyle and Peter Golenbock, The Bronx Zoo (New York: Crown Publishing, 1979).

3. Richard Goldstein, “Bob Wolff, Sports Broadcaster for Nearly 80 Years, Dies at 96,” The New York Times, July 16, 2017, https://www.nytimes.com/2017/07/16/sports/bob-wolff-dead-sports-broadcaster.html.

4. Wolff, vii; Author’s phone interview with Rick Wolff, February 4, 2022.

5. Author’s phone interview with Rick Wolff.

6. Author’s phone interview with Rick Wolff.

7. Author’s phone interview with Rick Wolff.

8. Author’s phone interview with Rick Wolff.

9. Author’s phone interview with Rick Wolff.

10. Dick Young, “Young Ideas,” New York Daily News, May 28, 1970: 99.

11. Author’s phone interview with Rick Wolff.

12. Author’s phone interview with Rick Wolff.

13. Author’s phone interview with Rick Wolff.

14. Author’s phone interview with Rick Wolff.

15. In contrast, Dirk Hayhurst’s 2010 account of playing in the San Diego Padres’ minor-league system, The Bullpen Gospels: Major League Dreams of a Minor League Veteran, frequently uses composites characters, based on people the author knew or played with. Dirk Hayhurst, The Bullpen Gospels: Major League Dreams of a Minor League Veteran (New York: Citadel Press, 2010).

16. Wolff, 143.

17. Wolff, 190-92.

18. Wolff, 213.

19. Wolff, 51.

20. Wolff, 33, 116-18.

21. Wolff, 147.

22. Wolff, 51-54.

23. Robert S. Cauthorn, “’Bull’ Director Intertwined UA Master’s in Art with Minor League Baseball,” Arizona Daily Star, June 15, 1988: 5B.

24. Wolff, 88-89.

25. Wolff, 53-54.

26. Wolff, 96-98.

27. Wolff, 81-84.

28. Wolff, 215-16.

29. Author’s phone interview with Rick Wolff.

30. Author’s phone interview with Rick Wolff.

31. Rick Wolff, “Triumphant Return,” Sports Illustrated, August 21, 1989.

32. Mitchell Nathanson, Bouton: The Life of a Baseball Original (Lincoln: Univ. of Nebraska, 2020), 316-17.

33. Author’s phone interview with Rick Wolff.

34. Author’s phone interview with Rick Wolff.

35. Author’s phone interview with Rick Wolff.

36. Author’s phone interview with Rick Wolff.

37. Author’s phone interview with Rick Wolff.

38. Author’s phone interview with Rick Wolff.

39. Author’s phone interview with Rick Wolff.