Heinie Wagner: A Speculative History

This article was written by Joanne Hulbert

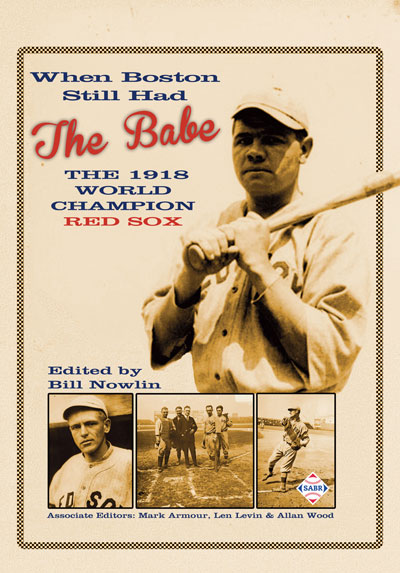

This article was published in 1918 Boston Red Sox essays

When Ed Barrow agreed to join the Red Sox organization in 1918, he intended to become the business manager and a prominent stockholder. Instead, Harry Frazee appointed him the team manager, thinking the former International League president could infuse new life in a team that ran out of steam during the 1917 season. Jack Barry would not be joining the team as manager nor playing at second base due to his military obligations as the war exceeded Frazee’s pre-season predictions.

When Ed Barrow agreed to join the Red Sox organization in 1918, he intended to become the business manager and a prominent stockholder. Instead, Harry Frazee appointed him the team manager, thinking the former International League president could infuse new life in a team that ran out of steam during the 1917 season. Jack Barry would not be joining the team as manager nor playing at second base due to his military obligations as the war exceeded Frazee’s pre-season predictions.

A contract was sent to Heinie Wagner in February of 1918, but abruptly, and much to the dismay of the sports reporters and fans, the aging player, coach and “right eye” of Bill Carrigan was unceremoniously handed his unconditional release. Manager Barrow

said he was looking for young blood to fire up the team, as he and Frazee announced that John Evers, of Chicago’s Tinker to Evers to Chance fame, and also late of the 1914 World Champion Boston Braves would replace Heinie; the young blood was a mere 10 months younger than his predecessor.

When Opening Day arrived, Dave Shean presided over the second bag while Johnny Evers, feeling abandoned, stood bereft in the grandstand, and Heinie Wagner was called back to resume his place as coach. Red Sox management remained mum on the subject saying only that they’d heard a rumor that the Newark club, and a few other clubs not named, were interested in his services and they would not stand in his way as he considered alternate plans for his future, please and thank you. The sports reporters were less kind, and had predicted Evers would have a hard time with teammates forced to endure his diatribes and sarcasm. One of the players declared Evers was so smart that he was incapable of understanding why they were all so stupid and had constantly harangued them when they made what he considered mistakes.

But now, Heinie was back, and a good thing, too, according to the fans. And a good thing, too, as it turned out in July, 1918 when Babe Ruth complained he was bored out there in the outfield and desired more time on the pitcher’s mound, jumped the team, called it quits when Barrow accused him of not keeping in condition, and ran off to Baltimore where he intended to play ball and build ships in the Steel League. Ruth vowed he has done with the Red Sox and done with major league ball, and the money offered by the industrial league was pretty good.

Frazee and Barrow, realizing that losing the Babe would be a huge blow to the team, and what with his contract and the reserve clause and the threat to future gate receipts and the run for the American League pennant, they came to their senses and concluded that offering Ruth some time pitching as well as playing the outfield was a small price to pay — but how to get him back in the fold? This was easy. Send Heinie Wagner, the Great Conciliator and Peacemaker to the rescue! And so it was done, and Heinie had his way-ward charge returned to the team in three days’ time.

Manager Barrow had been at the bottom of the argument that caused Ruth to quit the team, and was busy managing the rest of the team, so he could not possibly serve as the posse. Harry Frazee had no patience for actors nor ball players who did not live up to their contracts. What if, instead, John Evers had still been around and had made that trip to Baltimore?

Baseball history might have been very different. During spring training Evers reserved some of his best verbal beatings for the Babe. Seeing his face at his door would not have smoothed the way for a return to Boston. The Babe might well have stayed in Baltimore despite threats by Evers delivered from Barrow and Frazee, threats that might not have intimidated him in the least, and could rather have strengthened his resolve to stay away from Boston.

The Sporting News, in a scathing editorial published after Ruth’s brief hiatus, called for a blacklist of players who jumped their major league contracts to play for the shipbuilding leagues during the war. What if all that had happened?

Thank you, Heinie Wagner. There are many who need to line up and offer you their undying gratitude. For one thing, the Red Sox would not have won the 1918 World Series, and Yankees fans instead would have had to chant “Nine-teen Six-teen!” in 2004. The Babe would not have been available as trade bait for Harry Frazee in 1920.

The New York Yankees must give credit to Heinie Wagner for their glut of World Series rings. Following the Black Sox Scandal of 1919, Babe Ruth was instrumental in regenerating interest in the America’s National Pastime by his larger than life public image, and his ability to hit home runs that, according to Frederick Lieb, “revolutionized baseball, creating what seemed to be an entirely new game.” Major League Baseball’s career home run record contenders would now be chasing the Double X, aka the “Beast” – Jimmie Foxx – instead of Babe Ruth. There would be no Babe Ruth League for young players, no Babe Ruth movies, far fewer baseball books, and much less roar in the Roaring Twenties. American lexicographers and Paul Dickson’s Baseball Dictionary would be minus one adjective of colossal proportions: “Ruthian.”

So thank you, Heinie Wagner. You changed the course of baseball history and all of this might have happened if you had not been around to make that trip to Baltimore in July 1918.

JOANNE HULBERT is a co-chair of the SABR Boston chapter and is also co-chair of the SABR Arts committee. She regrets, despite spending countless hours accumulating 19th century and dead ball era poetry, and although finding poetry for all the other players on the 1918 Red Sox team, she has yet to find a masterpiece dedicated to Charles “Heinie” Wagner, truly an unsung hero. She has not given up the quest.