Henry Chadwick and the National League’s Performance vs. ‘Outsiders’: 1876-81

This article was written by Woody Eckard

This article was published in Fall 2023 Baseball Research Journal

At its 1876 founding, the National League presented the nascent professional baseball community with a business model radically different from that of its predecessor: the National Association of 1871–75. The key difference was membership restrictions that were widely criticized as arbitrary and elitist, and were not yet proven to be effective. Perhaps the foremost critic was Henry Chadwick, the leading baseball writer of the era and the only journalist enshrined in the National Baseball Hall of Fame in Cooperstown. He attempted to demonstrate that the league’s model was not superior by publicizing the many losses incurred by league clubs in their numerous exhibition games against outsiders. But he often failed to mention the always larger number of wins. This article hopes to set that record straight by summarizing, for the first time, the full results of those games during the key formative period of 1876–81.

The league’s successful 1880 and 1881 seasons (as we will discuss) confirmed the efficacy of its business model. In contrast, the National Association, with its erratic model, had failed, as had the minor International/National Association of 1877–80 that had adopted the NA’s model. In 1882, the American Association entered the field as a major league, using the league model, and had a generally successful 10-year run. Since then, the league model has been the dominant structure for baseball organizations, major and minor, and most other team sports organizations.

The first section that follows provides relevant background regarding early professional baseball. The second discusses in more detail Chadwick’s campaign to undermine the National League’s claim of superiority. The third section describes our data-gathering process. The results are then presented, covering more than 900 games between league and non-league clubs during 1876–81. National League teams won more than two-thirds of these games, contrary to Chadwick. The last section provides a summary and conclusions.

BACKGROUND

Professional baseball was first openly accepted for the 1869 season, but the first formal all-professional organization, the National Association, didn’t appear until 1871. Its main purpose was to provide structure for the national championship competition. Entry was essentially open, as any club could join simply by paying a nominal fee for a one-year membership. There were no other requirements, i.e., the NA was open to any and all comers. It somewhat resembled an annual tournament rather than a league as the word is now understood.

Mainly for this reason, the NA was highly unstable. Twenty-five different clubs participated over its five-year life, with the number varying annually from eight to 13.1 Some were relatively sound stock organizations with salaried players, mainly in big cities. Many others, however, often in small towns, were financially weak gate-sharing cooperatives, and still others were hybrids. The turnover was large, with 18 clubs competing in only one or two seasons. Also there were no fewer than 14 midseason failures, mostly co-ops, with at least one in every season. Only three clubs competed in each of the five years: the Athletics of Philadelphia, the Bostons, and the Mutuals of New York. The first season, 1871, began with nine participants. The NA also had a competitive balance problem, with the Boston Red Stockings winning four of five championships.

Dissatisfaction with the NA produced the National League, founded at a meeting in February 1876 whose true purpose was kept secret. It was organized by William Hulbert, president of the NA’s Chicago club. As with the NA, a main goal was to determine a national champion. Five other of the NA’s top clubs participated, including the mainstay Athletics, Bostons, and Mutuals, causing the NA to fold. The independent Cincinnati and Louisville clubs also were present at the meeting, with all seven attendees having been vetted by Hulbert beforehand. Not invited were any other clubs who might have had an interest in competing for the national championship, including other current and past NA members.

Also excluded from the meeting was Henry Chadwick, likely because he was presumed to favor the NA’s open organizational model over the league’s proposed restrictive model.2 In particular, membership was to be limited to eight stock clubs, only one per city, and only in cities with a minimum population of 75,000, although early exceptions were made to the population minimum. Last, the membership fee was increased substantially to $100 and, while it was still paid annually, membership was presumed to continue indefinitely until resignation or expulsion.3 The restrictions were designed to achieve league stability by promoting the financial success of clubs and minimizing midseason failures.

But the exclusion of other interested contestants for the national championship was criticized as arbitrary and elitist by many in the professional baseball community. For example, as business of baseball historian Michael Haupert notes, “Several newspapers spoke out against the league.”4 As Tom Melville observed in Early Baseball and the Rise of the National League: “The main criticism of the National League was its closed circuit format, the self-appointed right…to designate [the clubs] entitled to compete for the national championship.”5 Additionally, Chadwick accused Hulbert of having an unstated goal of usurping control of the professional game, which may indeed have been true. Many historians feel that he also took umbrage at his personal exclusion from the meeting, an affront to his image as America’s preeminent baseball writer.6

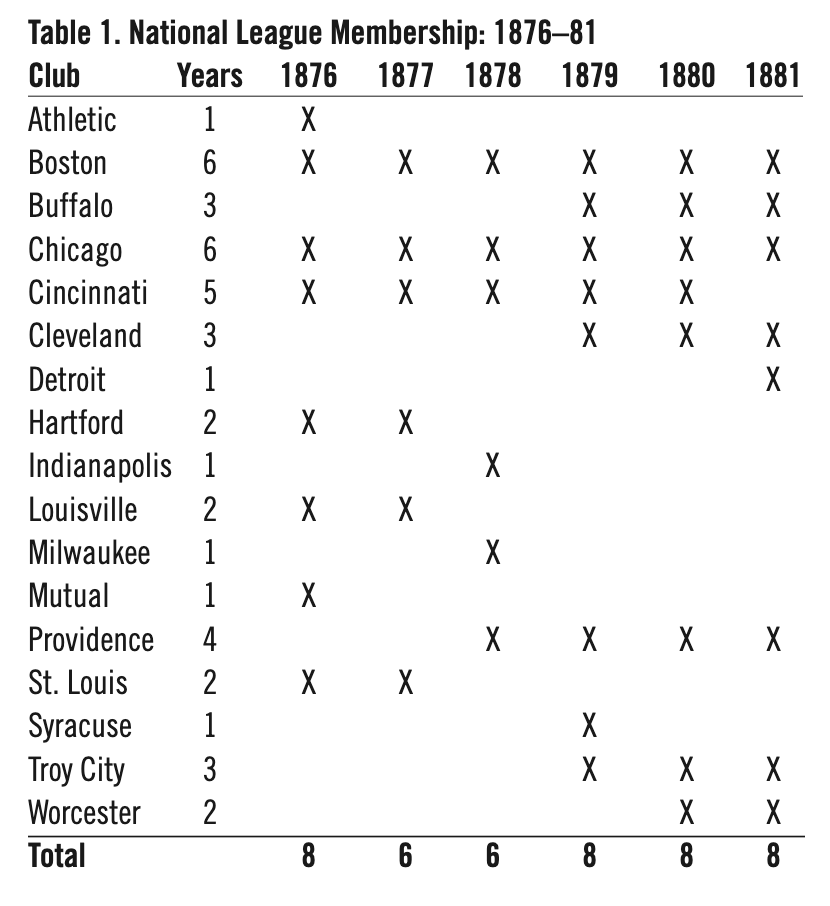

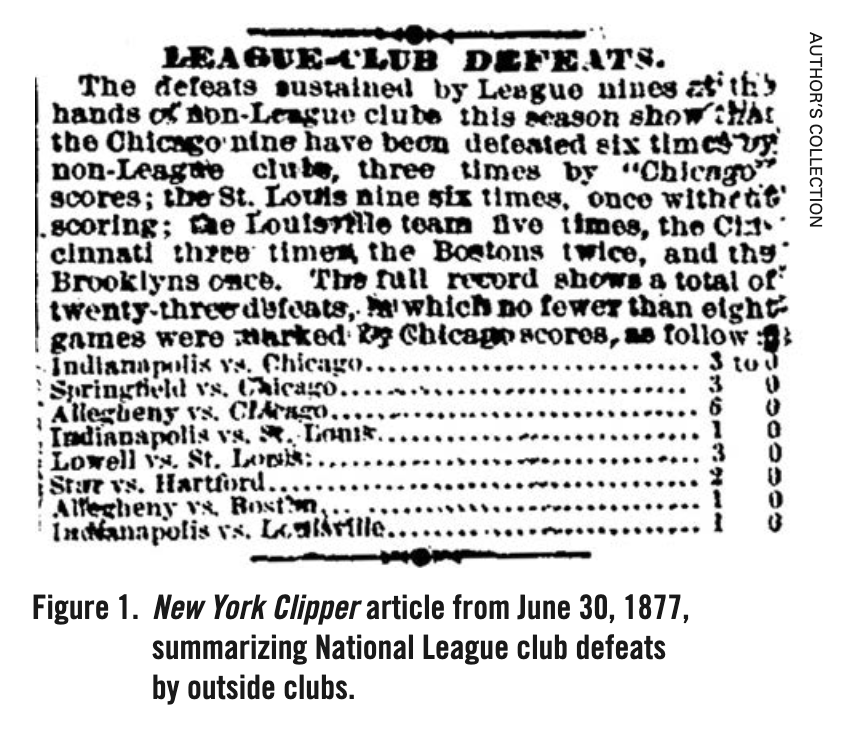

With the benefit of hindsight from a century and a half, the superiority of the league model seems obvious. But that was by no means clear at the time. While its performance during 1876–81 was an improvement over the NA, by modern standards it was still very much a work in progress. Table 1 summarizes league membership during this six-year period. It included 19 different clubs, with 11 competing in only one or two seasons. The 1877 Cincinnatis failed in June, but were quickly replaced with another Cincinnati club.7 And in 1879, Syracuse failed a few weeks before the season’s end, but with no replacement. By 1878, only two of the charter members remained: the Bostons and Chicagos, who participated in all six seasons.

But toward the end of the period, membership stabilized. In 1880, six of the eight clubs from the prior season returned, with a new club in Cincinnati, and in 1881 seven of eight returned. And in 1882, for the first time, league membership remained unchanged.

The economic depression that began in 1873 and lasted until March 1879 no doubt contributed to the league’s problems in its first few years.8 It was not a propitious time to initiate a major new business undertaking. For example, according to an official league statement published in August 1878, the “business depression has so far affected the receipts [of league clubs] that a loss is already assured.”9

The league also suffered from a balance problem. Table 2 shows the cumulative standings of the 17 clubs for 1876–81. Only six had a winning average above .500, and 45% of total wins were accounted for by just three clubs: Chicago, Boston, and Providence. And only two—Chicago and Boston—won five of the six championships.

Thus, during most of this formative period the jury was still out on the league and its unique business model.

CHADWICK’S CAMPAIGN

The league’s founding meeting occurred at a New York City hotel on February 2, 1876. On February 12, a lengthy article describing the meeting and its outcome appeared in the weekly New York Clipper, the leading national baseball newspaper at that time.10 It was the first mention of the meeting in the Clipper.11 Henry Chadwick was the Clipper’s baseball editor and, while the article had no byline, there can be little doubt that he was the author.

The article took a strong editorial position critical of the league. In fact, in The League That Lasted, Neil W. Macdonald describes Chadwick as “the leader of the reportorial minority who opposed Hulbert’s creation.”12 The Clipper article’s title referred to the league’s formation as “a startling coup d’état,” implying a hidden intent to displace the NA. The February 2 meeting was described as a “sad blunder,” “anti-American,” and “a star-chamber method of attaining the ostensible [objectives].”13

Chadwick, an ardent moral reformer, considered the main (and related) problems confronting professional baseball to be alcohol abuse and dishonesty, i.e., “the ‘selling’ or ‘throwing’ of games for betting purposes.” However, the league’s focus was on its organization and operation. Chadwick regarded business matters such as “confining the contests…to those [clubs] who are capable of carrying out the season’s programme” as merely a “supplement” to the more important moral issues needing attention.14 Furthermore, he believed that all these matters could be adequately addressed at the planned March convention of the still existing National Association. A new organization was unnecessary.

Chadwick’s antipathy towards the league did not fade quickly. One manifestation was his attempt to undermine the league’s position that its restrictive business model produced higher quality ballplaying, and he wasn’t the only such critic. For example, historian David Quentin Voigt notes that “in these years newspapers often ridiculed the league’s claim of major league status.”15 To this end, Chadwick periodically used the Clipper to point out that league clubs lost many of their numerous exhibition games against non-league opponents. These articles summarized losses, but league victories usually were not reported, a fact that revealed Chadwick’s agenda.

The first such article appeared in early September 1876, titled “Outside Club Victories.” It was self- described as “a record of victories won by ‘outside clubs’ against league-club nines from May to August” (emphasis added), followed by a list of 17 such games including club names and scores. It noted that “All but the Chicago and Louisville teams have had to succumb to outsiders, and the New Havens have defeated league nines eight times.”16 The New Haven Club had been a NA member that sought and was denied admission to the league. The article did not mention league victories.

The 1876 record was completed in another Clipper article in late February 1877 titled “League Club Defeats.” It was self-described as “a record of the outside defeats sustained by league clubs at the hands of non-league nines in 1876.”17 The list included 37 games with club names and scores. The article title implied all were defeats, but by my count there were 33 defeats plus four ties. As Macdonald notes, quoting an 1876 Chicago Tribune article: “they probably won far more; ‘but Chadwick, demonstrating his prejudice against the League’s claim of superiority, never tabulated their wins.’”18 David Nemec makes the same point in The Great Encyclopedia of Nineteenth Century Major League Baseball regarding Chadwick’s tabulations.19

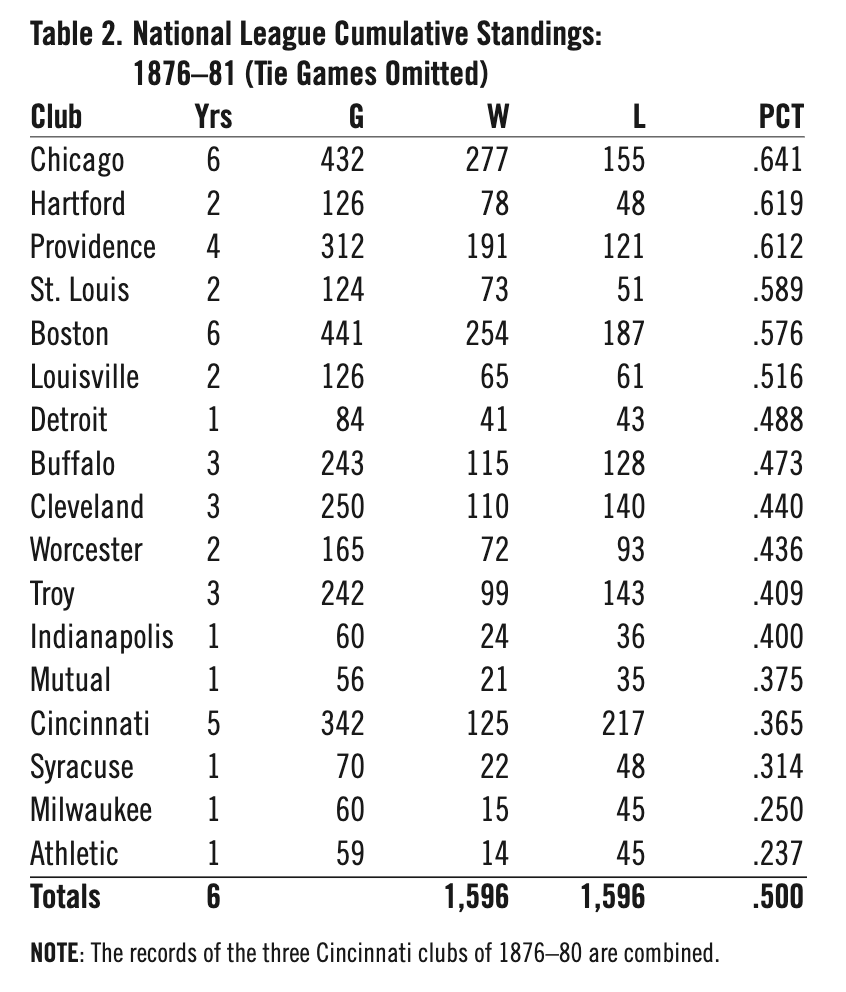

Figure 1 shows the Clipper’s 1877 midseason reckoning of league outsider defeats, published on June 30.20 It reports 23 such defeats by that date, including eight in which the league club was “Chicagoed,” i.e., shut out. Once more, no league victories were mentioned. The Clipper summarized the league’s complete 1877 experience with outsider clubs in late December as follows:

Last season it was plainly evident that too many outside games were played by League nines. What with the frequency of such contests, and the number of defeats League clubs sustained at the hands of outside teams—seventy-two in all during the season—the prestige of League nines was so weakened as to materially lessen the power to draw paying crowds. (Emphasis added.21)

The claimed financial impact was not otherwise supported. Eight months later, the Clipper published the abovementioned league statement attributing financial difficulties at that time to the ongoing economic depression and made no mention of outsider losses affecting profits. Also, 1877 was the second season in which league losses against outsiders were presented with no mention of wins.

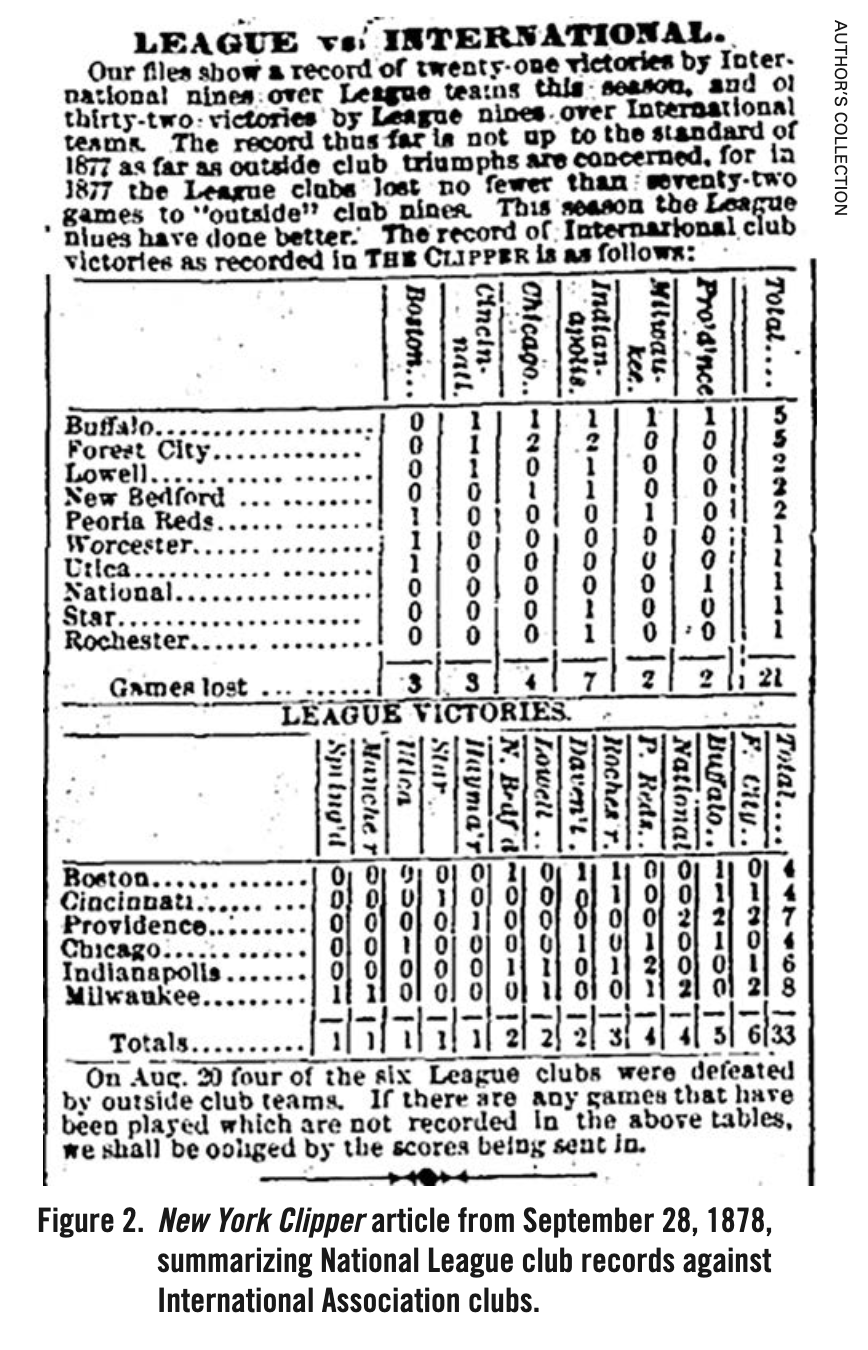

After 1877, Chadwick switched his focus from all outside clubs to members of the minor International Association. It operated from 1877 to 1880 and included some of the strongest non-league clubs.22 Figure 2 shows the Clipper’s detailed 1878 summary titled “League vs. International,” although the two tables actually include a few clubs not involved in the International championship competition.23 The article was published at the end of September, a month before the season concluded. Other clubs belonged to the International, but played no games against the league. The tables show that the league lost 21 games against these significant outsiders, but also won 33. League victories were included for the first time.24 Note that the accompanying text repeats 1877’s loss record against (all) outsiders: “no fewer than seventy-two games,” again with no mention of wins.25

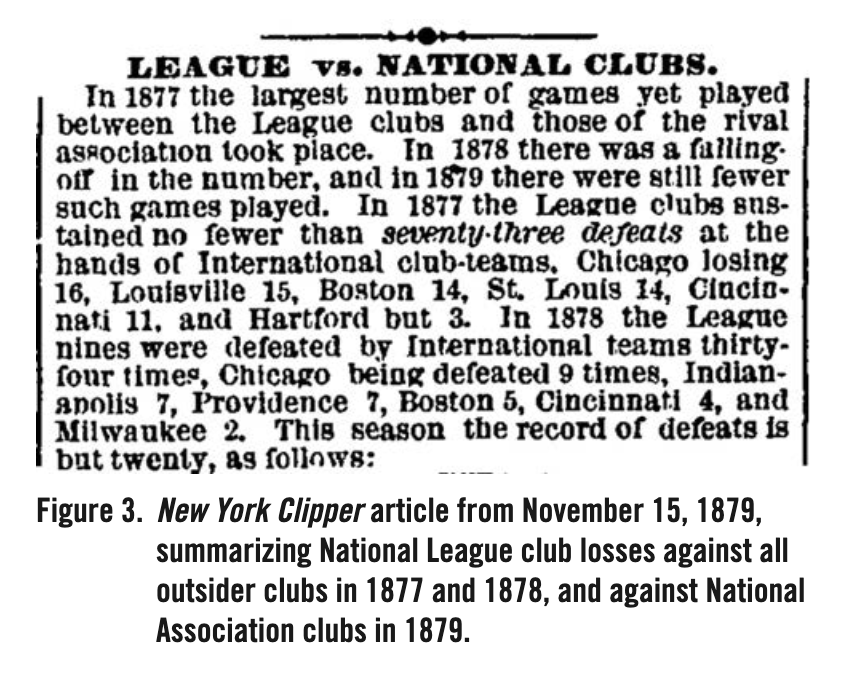

Figure 3 presents the text from the Clipper’s November summary of 1879 league results against the minor National Association, a continuation of the International.26 First, it updates the 1878 league outsider loss record to include all games that year (see above), with losses increasing from 21 to 34.27 However, 1878 wins were not updated (or mentioned). Second, the 1877 record of (all) league outsider losses is again repeated; now stated as 73 and again with no mention of wins; and it is erroneously attributed to International Association clubs only. The 1879 article also contained separate lists of 1879 games won and games lost against six National Association clubs, with scores, which are excluded from Figure 3 to save space.28 The text states that “the record of defeats is but twenty,” but my count for the “League Defeats” list is 19.29 The “League Victories” list contained 26 wins, plus four draws.30

The 1880 summary was titled “League vs. National” and contained a single sentence of text: “The following is the record of the games played up to the 9th of August between the League and National club teams.”31 The National Association that summer was a rump organization with only four clubs and, in fact, had folded at the end of July. The summary included a list of 53 games with scores, but a count of losses or wins was not provided. By my count, this small group had an 18–33–2 record against the National League.32

The wording of the September 1881 summary suggests that Chadwick may have mellowed somewhat toward the league. While its title—“League Club Defeats”—retains the emphasis on losses, the text reads: “Apart from the [New York] Metropolitan Club victories, there have been but five defeats of League nines this season by other clubs, the smallest number on record.”33 A postseason Clipper article presented a detailed review of the Metropolitans’ games against the league, reporting an 18–42 record.34

To my knowledge there has been no complete enumeration of the National League record against non-league clubs during this formative period. The selective and biased reporting of the Clipper summarized above, covering an incomplete sample of such games, appears to be the best existing source.

Reliance on the Clipper data, however, can adversely impact historical analysis, inadvertently incorporating similar biases. For example, Tom Melville, in discussing the 1876 season, concluded: “Though the [National League] claimed to represent baseball’s highest competitive echelon, their competitive record against non-National League clubs over the 1876 season raised serious doubts about this. [The league] lost no less than 37 times [sic] to outside clubs that year.”35 Similarly, the 72 (or 73) league loss figure for 1877 noted in the abovementioned Clipper article covering that year, then repeated in 1878 and 1879 articles, has been accepted in several modern histories as a reliable indication of league club vulnerability vis-à-vis non-league clubs.36

DATA COLLECTION

Our objective is to obtain a list of game results for National League clubs against non-league clubs during the period 1876–81, as complete and accurate as possible. All League clubs were fully professional stock companies with salaried players. Outside clubs, however, were organized in a variety of ways, on a continuum from fully professional to fully amateur. And the extent of press coverage declined moving toward the amateur end of the continuum.

Some outside clubs, usually the strongest, were organized like league clubs, although these were a minority. Many others were gate-sharing cooperatives, with players splitting the net proceeds after covering costs like playing field rental, equipment, and travel expenses. And hybrid forms existed where some players were salaried, such as the pitcher and catcher, and the remainder shared gate money. Semiprofessional teams had a mix of paid and amateur players. And some were purely amateur, although these were scarce by the late 1870s. Apparently a significant proportion of those claiming amateur status at this time secretly paid at least a few team members. For example, in 1876 the Clipper reported that “Mr. Chadwick has resigned his position as Chairman of the Committee of Rules of the Amateur Association, nearly all the clubs having become semi-professional organizations.”37

While an “apples-to-apples” comparison in terms of club professional status would be desirable, as a practical matter this can only rarely be determined for individual clubs. We therefore include all non-league clubs, except “picked-nines,” in our enumeration of outsiders without attempting to distinguish among them by professional status.38 To partly deal with this issue, we report separate results for league clubs against the minor International/National Association of 1877–80, whose members were mostly, if not entirely, fully professional.

The primary source for individual game results was the weekly New York Clipper, which, as noted above, was the main national baseball newspaper of the period.39 Each issue during the season contained extensive coverage of game results and various additional news items covering a wide variety of clubs. All league championship games were reported along with league games with outsider clubs and outsider vs. outsider games. Usually an individual game report included a box score and a brief game synopsis, although the latter could sometimes be extensive. If box scores were not available, line scores were reported or sometimes simply the final game outcome.40

The first step in the collection process was a review of every issue of the Clipper during the seasons of 1876 through 1881, identifying games between league clubs and outsiders and entering the results in a spreadsheet.41 For various reasons, the Clipper reports could be erroneous and some games may have been overlooked. For example, the last sentence in the Clipper article of Figure 2 specifically requests readers to send in the scores of “any games that have been played which are not recorded in the above tables.”

The second step was to confirm the Clipper– reported results with a report in another newspaper via searches on newspapers.com. A variety of papers were used, although the Boston Globe, Chicago Tribune, and Cincinnati Enquirer were most common, as they were the main baseball-reporting papers for the three principal league cities over our full study period. Reviewing all games reported in the papers used for confirmation also provided an opportunity to identify those missed by the Clipper. These were then confirmed by locating a second game report in an another newspaper via newspapers.com. If, say, the number of runs reported for the teams differed between two papers, a third was consulted to resolve the “dispute.”

The resulting enumeration yielded over 900 games during the six years. While, of course, care was taken in the process, errors of both commission and omission may remain, despite the double checking of each game result.

Before presenting the results of these exhibition games, however, some caveats are in order. First, player motivation was likely lower in these non-champion-ship contests, although league clubs needed to be careful lest losses to weak outsiders damage their “brand,” including raising suspicions of “hippodroming,” as game-fixing was called. Second, one must keep in mind that league clubs often did not have their “A” team on the field. Exhibitions were an opportunity to, e.g., provide the “change” pitcher and/or catcher some practice, as well as any reserve players. Another factor was that league rules meant that these games were usually on the opposing team’s home field, often meaning a home team umpire. And the outsider’s players may have had added motivation, perceiving the game as a “tryout” for the league visitors. Thus, the Outsider’s overall performance in these exhibitions must be viewed as, at most, only an upper bound on their quality relative to the National League.

THE LEAGUE RECORD AGAINST OUTSIDERS

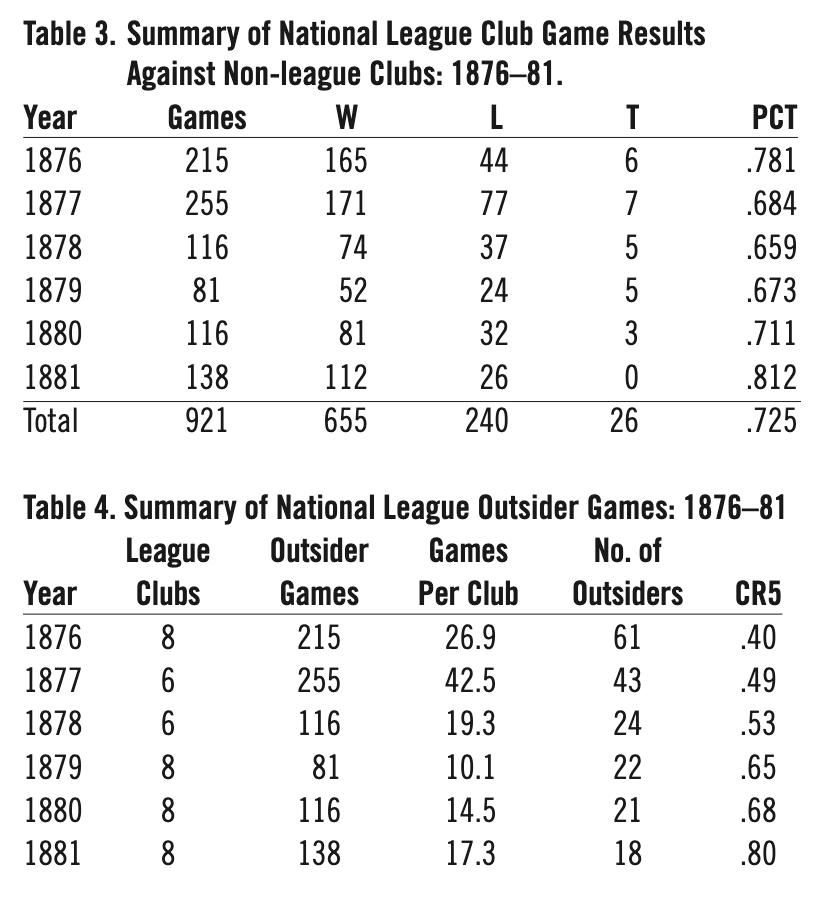

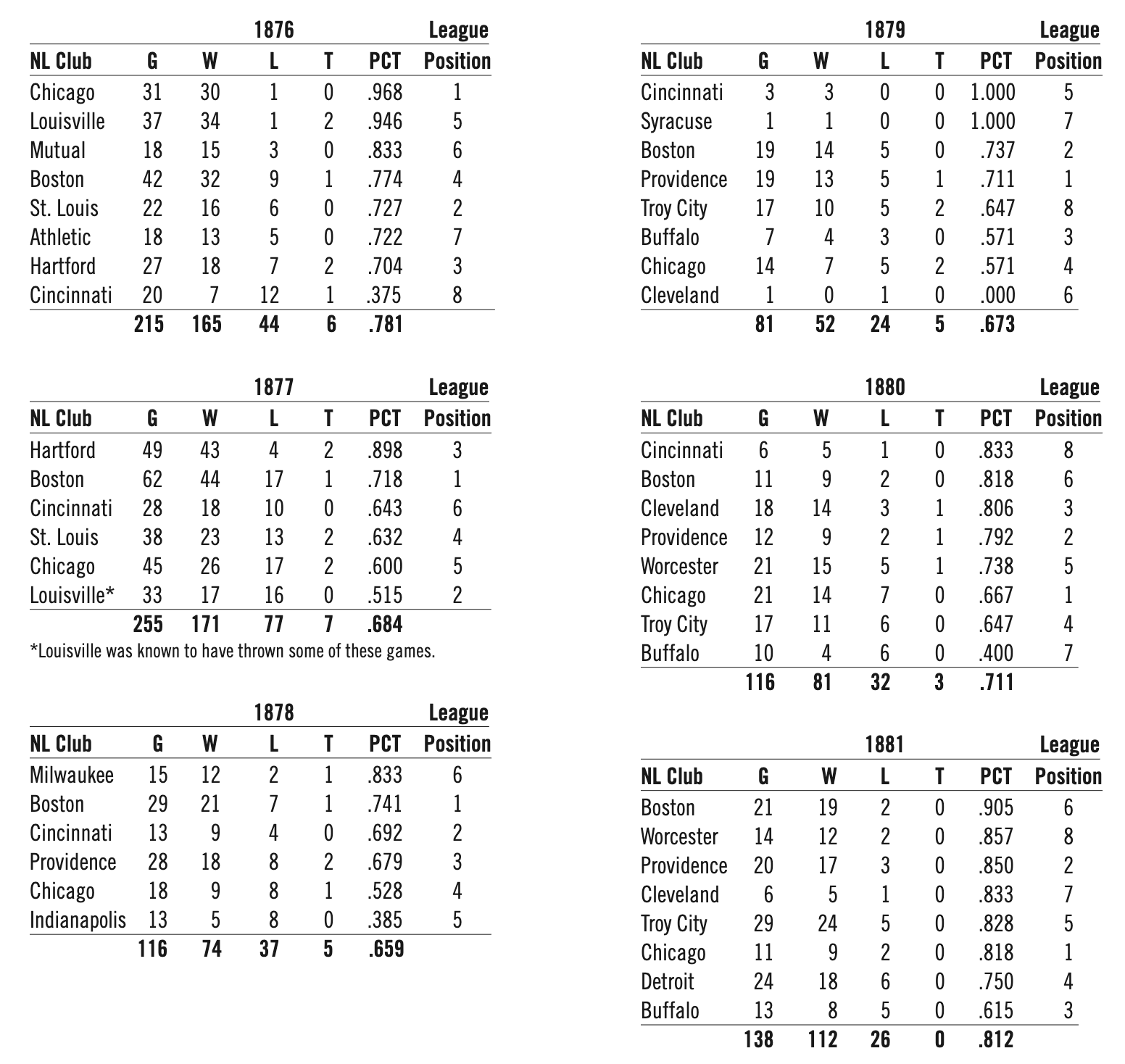

Table 3 summarizes the overall league won-lost record against non-league clubs for each of the six years of our study period. The appendix provides the yearly results for individual league clubs. We identified a total of 921 outsider games, of which league clubs won more than 70 percent. In individual years, the winning averages are similar, varying from .659 (1878) to .812 (1881). Certainly the league was doing very well against outsiders, despite Chadwick’s insinuations.

We can conduct a formal statistical test of the implicit Chadwick hypothesis that league and non-league clubs were of equal quality. If true, then over our six-year study period, the league winning average against outsiders should average close to .500. In fact, the mean of the six yearly averages was .720. We can perform a t-test to determine the likelihood of observing our average (or a larger one) in a six-year sample if the underlying true average is .500.43 The resulting t-test statistic is 8.63 with a p-value of 0.00034, indicating the chance that the hypothesis is true is less than one in 1,000. Thus, we can be very confident that the league clubs were, on average, superior to non-league clubs.

Chadwick’s reports of league losses to all outsiders in 1876 and 1877 can now be put into perspective. He reported 33 losses in 1876, plus four ties, although our search yielded 44 losses and six ties. But he failed to mention that 215 games were played and that the league won 165, well over three times the losses. Similarly, in 1877 Chadwick tabulated 72 (or 73) losses, while we found 77, plus seven ties. Again, he fails to mention the much larger number of games played, 255, of which the League won 171, over twice the number of losses. With the losses “scaled” correctly, it appears that the league was doing very well against outsiders. And recall that, as noted above, these comparisons most likely underestimate the league’s superiority.

Table 4 provides additional analysis of outsider games. First, the total number varied significantly, from 255 in 1877 to only 81 in 1879. Notable is the fact that just over half of all games—470, or 51%, occurred in the first two years. The annual average per club increased from 26.9 games in 1876 to a high of 42.5 in 1877. This may have been due partly to more open schedule slots caused by a drop in the membership from eight clubs to six and a reduction in the number of championship games per team by 10 from 70 in 1876 to 60 in 1877.

But after 1877, the per-club average dropped by more than half to 19.3 in 1878, followed by a further drop in 1879, again almost by half, to only 10.1. The large 1878 drop was likely due to new league regulations that significantly limited the number of outsider games. Games were pushed to the postseason, by which time many outside clubs had failed. For example, the December 1877 league convention ruled that “no league club can play a game with any organized club prior to the commencement of the League season, nor can any club play on its grounds a game with any club outside of the League during the League season.”44 The additional 1879 drop was likely caused by an increase in the number of championship games per team from 60 to 84 as the league returned to an eight club format and also increased the championship games required with each other team from 10 to 12. The average number of outsider games then rose in 1880 and again in 1881, perhaps due to the general economic recovery beginning in the Spring of 1879 (see above), which may have made such games more profitable.

Column 5 of Table 4 shows the annual number of different outsider clubs involved in games with the league. There were 61 in 1876, but two years later there were only 24. After that, the number decreased gradually to 18 in 1881. The large drop from 1876 to 1878 may have been caused in part by the economic depression and its impact on the number of outsider clubs available as opponents. The last column addresses the distribution of games among the outsiders, i.e., whether the games were concentrated mainly among a few clubs. The data shown are the averages of all outsider games accounted for by the top five clubs in terms of games played, called the “five-club concentration ratio” or CR5.45 The distribution was far from even, as the top five outsiders had 40 percent of league games in 1876, increasing to 65 percent in 1879 and finally to 80 percent in 1881.

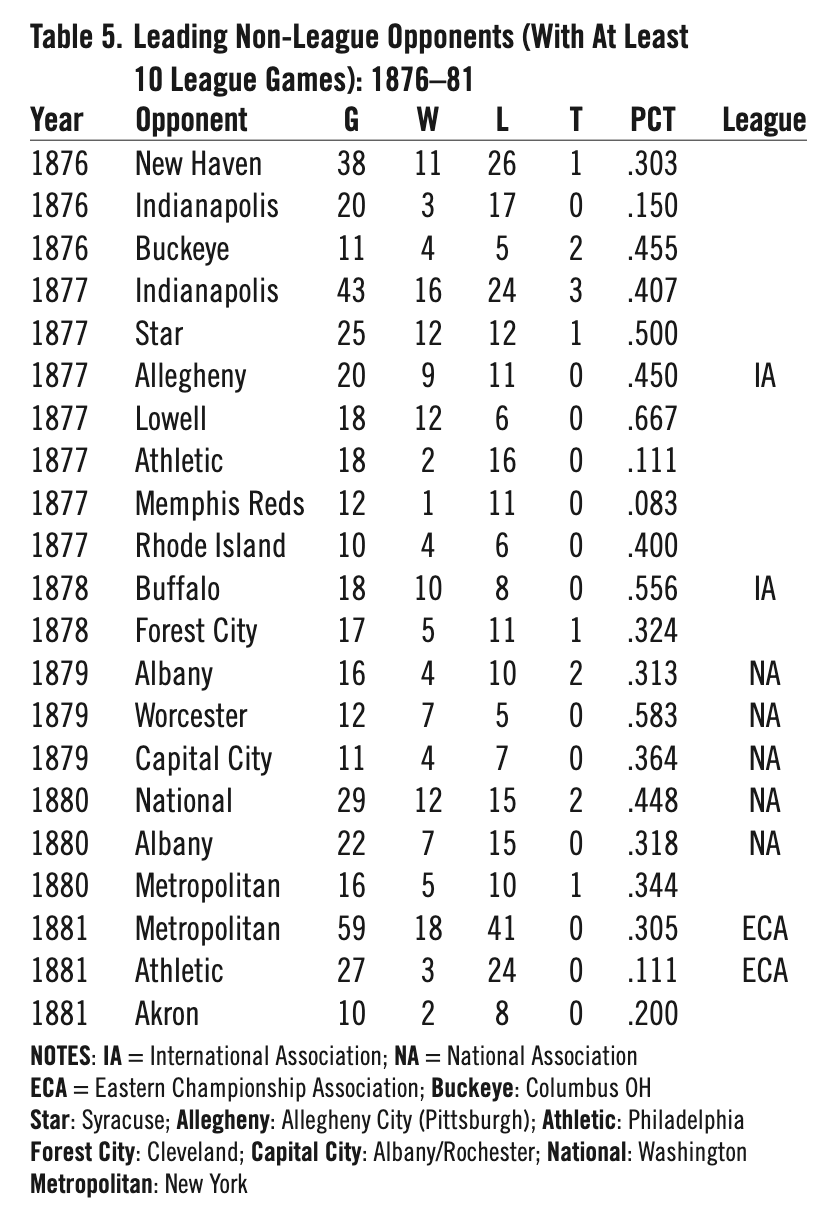

Table 5 shows the main outsider opponents by year, defined as those with at least 10 league games, a total of 21 such teams during the study period. New York’s Metropolitan Club of 1881 led with 59 games, followed by Indianapolis with 43 in 1877, and New Haven at 38 in 1876. Six other clubs had at least 20 games in one season. The only clubs among those with 10-plus games that broke even or better against the league were the Lowells, at 12–6 in 1877; the Worcesters, at 7–5 in 1879; the Buffalos, at 10–8 in 1878; and the Stars of Syracuse in 1877, at 12–12–1.46

Six of these primary outside opponents subsequently were “promoted” to the National League. At the December 1876 annual meeting, the league added a constitutional provision describing the circumstances under which an outside club would be “eligible to membership in this League.” The door was opened for admitting outside clubs.47

First, the Indianapolis club, with 20 games in 1876 and 43 in 1877, joined the league in 1878 along with their pitching phenom “The Only” Nolan. The Rhode Islands, with 10 games in 1877, also were admitted in 1878 as the Providence Club, winning the National League championship the next year. The Star Club, after 25 games as an independent in 1877 and another seven in 1878 as a member of the International Association, was admitted to the league in 1879 as the Syracuse club.48 The Buffalos, with 18 games in 1878, also were admitted in 1879 and finished third. Another 1879 promotion was Forest Cities, with 17 games in 1878, admitted as the Cleveland club. Last, the Worcesters, with 12 games in 1879, joined in 1880. Indianapolis and Syracuse lasted only one season, but the other four continued through to 1881.

Thus, by 1881, half of the eight league members were former significant outsider opponents. While, on average, non-league clubs were certainly below National League quality, the league itself evidently considered at least this small group of clubs to be major league.49

In addition, the league’s top two opponents by games played in 1881 later joined the new American Association. The Athletics of Philadelphia, with 27 league games in 1881, became a charter member in 1882. And the Metropolitans of New York, with 16 league games in 1880 and 59 in 1881, joined the AA in 1883 after a year as an independent.

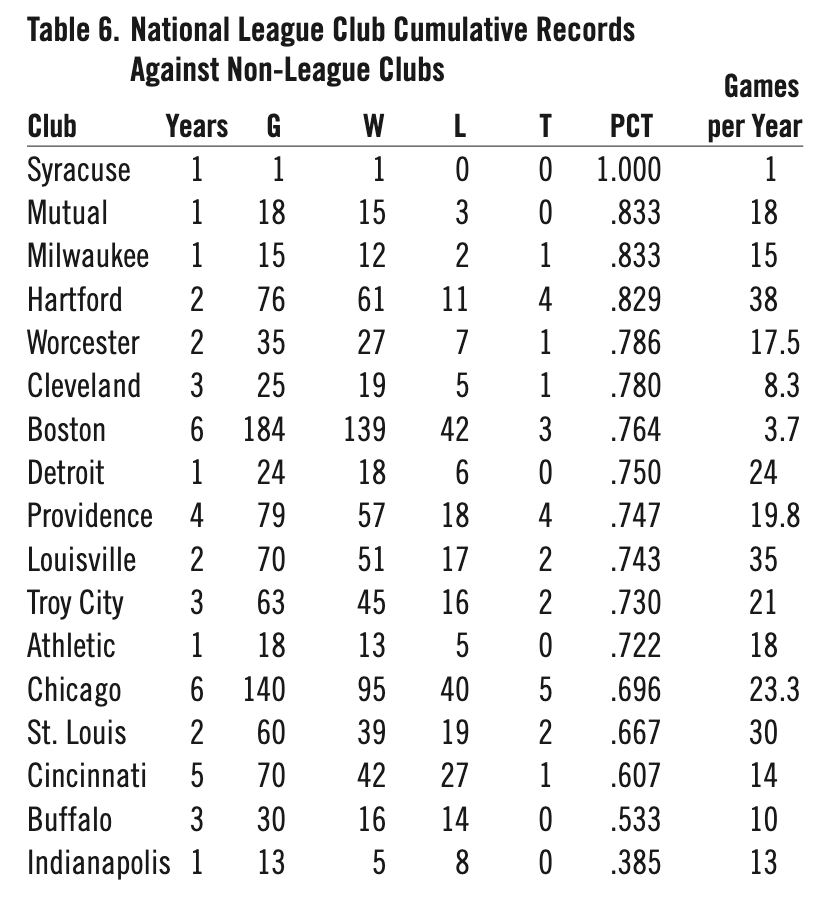

Table 6 shows the cumulative record of National League clubs against outsiders. Notable is the fact that only one club, Indianapolis, has a sub-.500 winning percentage, and that only for one year. Consistent with our statistical test results above, this would be very unlikely if the league and outsider clubs were of equal quality, per Chadwick.

Table 6 also reports the average number of outsider games played per year by each club, although the results are distorted by the above-mentioned concentration of such games in the first two years. Five of the first six clubs ranked by average games were active in both 1876 and 1877. While the Bostons and Chicagos alone accounted for more than one-third of all outsider games, they ranked only seventh and 14th in winning percentage. Syracuse’s single outsider game in its only year of league membership could indicate some missing games, or it could have resulted from the club’s disbanding on September 10, three weeks before the championship season ended, i.e., before league rules permitted significant outside play.

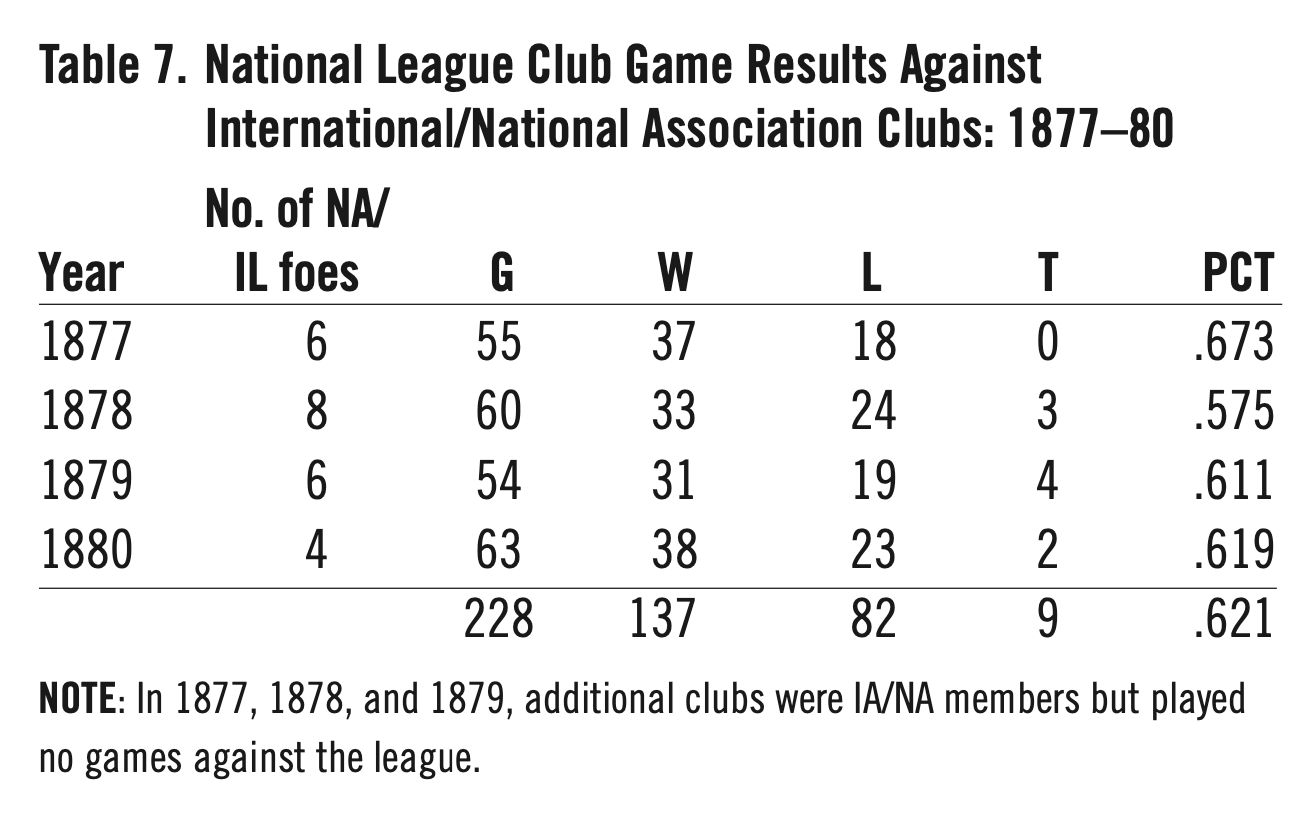

As noted above, a comparison of National League clubs to non-league clubs that also were fully professional would be desirable. While we can’t make this determination for all outside clubs, the International/ National Association of 1877–80 had a membership that, for the most part, was fully professional. Table 7 presents the league’s record against the IA/NA, an average of six clubs per year. While few in number, during 1878–80 they nevertheless accounted for more than half of the league’s outside games.50 The annual winning averages varied from .575 to .673. The overall average of .621 was lower than the league’s overall average of .725 against all outsiders reported in Table 3. Thus, this group apparently had higher quality clubs than other outsiders.

Nevertheless, by the same statistical test conducted earlier, the league is superior by a statistically significant amount. Again, the null hypothesis is equal quality, i.e., an expected league winning average of .500. The significance test yields a t-test statistic of 5.92 and a p-value of 0.010. Thus, there is a chance of only about one in 100 that the equal-quality hypothesis is true.

SUMMARY AND CONCLUSIONS

The National League’s 1876 founding created controversy in professional baseball circles. Chief among critics was premier baseball journalist Henry Chadwick, who used his position as baseball editor of the New York Clipper to conduct a campaign aimed at undermining the league’s prestige. In particular, he publicized the many losses of league clubs in exhibition games against outsiders, generally ignoring the fact that there were many more victories. His presumed intent was to create the impression that there was little quality difference.

To correct this impression, the present article summarizes the results of all National League games against outsider clubs, losses and wins, for the formative period of 1876–81. To my knowledge, this is the first such enumeration. Our online search of contemporary newspapers yields 921 outsider games, an average of 154 per year. National League clubs won over 70 percent against all outsiders during the full period and over 80 percent in the final year. Also, they won almost two-thirds of their 228 games with International/ National Association clubs, most fully professional, during 1877–80. Certainly, they did very well against non-league clubs and formal statistical tests leave little doubt that league clubs were superior.

Nevertheless, some outsiders were competitive with the National League. In fact, during 1878–80 six such clubs were admitted, all having been significant opponents prior to joining. One finished third in its initial league year and another won the championship in its second year, although two others lasted but one season. Also, three outsiders that played at least a dozen league games sported winning records. Thus, Chadwick might have been partially correct: While National League clubs were clearly superior to the great majority of outsiders, there was no bright line separating league and non-league clubs circa 1880 such as exists today between the major and minor leagues.

WOODY ECKARD, PhD is Professor of Economics Emeritus at the University of Colorado-Denver Business School. His academic pub- lishing record includes several papers on sports economics. More recently he has published in the BRJ, The National Pastime, and Nineteenth Century Notes. He and his wife Jacky live in Evergreen, Colorado, with their two dogs Petey and Violet. He is a Rockies fan, both the baseball team and the mountains, and a SABR member for over 20 years.

Acknowledgments

Notes

1 David Nemec, The Great Encyclopedia of Nineteenth Century Major League Baseball 2nd edition (Tuscaloosa: University of Alabama Press, 2006); William J. Ryczek, Blackguards and Red Stockings: A History of Baseball’s National Association, 1871-1875, Revised Edition (Jefferson, NC: McFarland & Company, (2006); Baseball Reference, https://baseballreference.com.

2 Michael Haupert, “Pulling Baseball from a Slough of Corruption and Disgrace: The Origin of the National League, the 1875 Winter Meetings,” Baseball’s 19th Century“Wintef Meetings: 1857-1900, Jeremy K. Hodges and Bill Nowlin, eds. (Phoenix: Society for American Baseball Research, 2018). The only member of the press invited to the meeting was Lewis Meacham of the Chicago Tribune, a Hulbert supporter.

3 Adjusting for inflation, $100 in the mid-1870s would be worth roughly $2,700 today, per the Federal Reserve Bank of Minneapolis, https://www.minneapolisfed.org/about-us/monetary-policy/inflation-calculator/consumer-price-index-1800-.

4 Haupert, “Pulling Baseball”: 137.

5 Tom Melville, Early Baseball and the Rise of the National League (Jefferson, NC: McFarland & Company, 2001), 81.

6 See, e.g., Neil W. Macdonald, The League That Lasted: 1876 and the Founding of the National League of Professional Base Ball Cubs (Jefferson, NC: McFarland & Company, 2004), 61; John Thorn, Baseball in the Garden of Eden: The Secret History of the Early Game (New York: Simon & Schuster Paperbacks, 2011), 163.

7 Woody Eckard, “The 1877 National League’s Two Cincinnati Clubs: Were They In or Out, and Why the Confusion?” Baseball Research Journal 52, no. 1 (2023). The second club began play a few weeks after the first club failed, with the same name but different ownership, and completed the original club’s league schedule. Today, MLB combines the records of the two clubs, showing them as a single league member, although after the 1877 season the league excluded both clubs from its final standings.

8 “US Business Cycle Expansions and Contractions,” National Bureau of Economic Research, https://www.nber.org/research/data/us-business-cycle-expansions-and-contractions, accessed September 12, 2023.

9 “The League Meeting,” New York Clipper, August 17, 1878, 162.

10 “National League of Professional Clubs [sic]: A Startling Coup d’Etat,” New York Clipper, February 12, 1876, 362. The Clipper billed itself as “The Oldest American Sporting and Theatrical Journal.”

11 “The Centennial Campaign,” New York Clipper, February 5, 1876, 357. The Clipper of February 5 contained a lengthy article on the upcoming 1876 season, but made no mention of the February 2 meeting or the National League.

12 Macdonald, The League That Lasted, 61.

13 “National League of Professional Clubs [sic]: A Startling Coup d’Etat,” New York Clipper.

14 “National League of Professional Clubs [sic].

15 David Quentin Voigt, American Baseball, Vol. 1, From the Gentleman’s Sport to the Commissioner System (University Park, PA: Pennsylvania State University Press, 1983), 77.

16 “Outside Club Victories,” New York Clipper, September 2, 1876, 181.

17 “League Club Defeats,” New York Clipper, February 24, 1877, 378.

18 Macdonald, The League That Lasted, 207.

19 Nemec, The Great Encyclopedia, 115.

20 “League-Club Defeats,” New York Clipper, June 30, 1877, 107.

21 “The Work of the League,” New York Clipper, December 22, 1877, 309.

22 See David Pietrusza, Major Leagues: The Formation, Sometimes Absorption and Mostly Inevitable Demise of 18 Professional Baseball Organizations, 1871 to Present (Lemur Press, 2020 [1991], Chapter 3, https://lemurpress.com. Chadwick became a “cheerleader” for the newly formed International Association, which had aspirations to challenge the National League, providing supportive coverage in the Clipper.

23 “League vs. International,” New York Clipper, September 28, 1878, 210.

24 The Star Club listed in the upper table was from Syracuse.

25 “League vs. International,” New York Clipper.

26 “League vs. National Clubs,” New York Clipper, November 15, 1879, 269. The International Association changed its name after its two Canadian members had withdrawn.

27 Beadle’s Dime Base-Ball Player 1879, edited by Chadwick, lists the 34 1878 lost games on page 52.

28 Three other clubs were involved in the National Association’s championship competition, but played no games against the league.

29 “League vs. National Clubs,” New York Clipper.

30 Our reckoning of the National League’s 1879 record against the National Association is 31-19-4, i.e., identical losses and ties but five more wins (see Table 7).

31 “League vs. National,” New York Clipper, August 21, 1880, 170.

32 Our reckoning of the National Association’s 1880 record against the National League is 23-38-2, i.e, adding five wins and five losses. After August 9, only two former NA clubs were still active.

33 “League Club Defeats,” New York Clipper, September 10, 1881, 397.

34 “The Metropolitan Club Season: Their League Club Record,” New York Clipper, October 22, 1881, 498. The author’s research finds an 18-41 record for the 1881 Metropolitans (Table 5).

35 Melville, Early Baseball and the Rise of the National League, 83

36 For example, see Harold Seymour, Baseball: The Early Years (New York: Oxford University Press, 1960), 94; Melville, Early Baseball and the Rise of the National League, 83; and Thorn, Baseball in the Garden of Eden, 170.

37 “Short Stops,” New York Clipper, October 7, 1876, 219.

38 One suspects that even the few top college teams that played National League clubs were subsidizing, i.e., paying, at least some of their players.

39 For 1877, the Beadle’s Dime Base-Ball Player 1878 guidebook was also used. It contains an incomplete list of 1877 game results (single-figure scores only) for 38 non-league clubs, including games against league clubs (33-57).

40 Retrosheet lists 618 NL exhibitions 1876-81, whereas I found 921.

41 New York Clipperissues can be accessed via the Illinois Digital Newspaper Collections, University of Illinois Library: https://idnc.library.illinois.edu/?a=cl&cl=CL1&sp=NYC&e=en-20–1–txt-txIN

42. Throughout, we calculate winning percentages counting ties as a half game won and a half game lost.

43 The sample of six years is small, but the student-t distribution, in effect, adjusts for this.

44 “League Association Convention,” New York Clipper, December 15, 1877, 298. For more discussion of these regulations, see also “League Nine [sic] vs. Non-League Teams,” New York Clipper, May 10, 1879, 50.

45 The concentration ratio is a statistic often used in the economic analysis of markets, e.g., to measure the concentration of sales among firms in a particular market.

46 In fact, the Lowell Club of 1877 was likely as good, and perhaps better, than the National League champion Bostons. See Eckard, “Lowell Base Ball Club of 1877: National Champions?” Nineteenth Century Notes (SABR), Bob Bailey and Peter Mancuso, eds. (Summer 2022).

47 Haupert, “Pulling Baseball”: 144.

48 The league required its members to bear the name of the cities they represented.

49 Of these four cities, only Worcester’s 1880 population of 58,291 was less than the league’s avowed minimum of 75,000.

50 See Tables 3 and 7.