Herb Washington’s Value to the 1974 A’s

This article was written by Scott Schleifstein

This article was published in Summer 2009 Baseball Research Journal

Two weeks before the start of the 1974 season, Oakland Athletics owner Charles O. Finley signed Herb Washington as a “designated runner”—in the long, storied history of Major League Baseball, the first and only player whose sole responsibility was to run the bases. Baseball historians and fans have not treated “Hurricane Herb” Washington kindly over the years. Washington is often cited as a sideshow à la Bill Veeck’s midget Eddie Gaedel—as an example of Finley’s flamboyant if not downright bizarre ownership style or as just some kind of strange joke. One pundit dubbed Washington “the most superfluous (hence greatest) hood ornament on the biggest, baddest Blue Moon Odomest Cadillac in the league.”1

On learning that he had collected 29 stolen bases in his only full season in the majors, I had as my original intention in writing this article to recall and honor Washington’s achievement. I saw Washington as vaguely heroic, the star of a reality-TV drama, “So You Want to Be a Major League Baseball Player?” The establishment, save Finley, expected Washington to fall on his face (figuratively, if not literally), making him the ultimate underdog. Surely, I thought, my research would prove that the critics were wrong in their hasty, probably mean-spirited dismissal of Washington. I knew in my heart that those 29 stolen bases had to mean something, especially since the A’s were world champions in 1974.

ALLAN LEWIS, “THE PANAMANIAN EXPRESS”

Perhaps the best place to start is with the man to whom the A’s previously assigned their pinch-running duties: Allan Lewis. Lewis began his career with the Kansas City Athletics in 1967. During his career (which ended with his release after the 1973 season), Lewis stole 44 bases in 61 attempts for a 72.1 percent success rate. Lewis’s highest yearly stolen-base total was 14 in 1967.

Although theoretically Lewis could hit and field, he did neither with much proficiency. A’s manager Dick Williams commented that “he was strictly a runner. I don’t know if Lewis even owned a glove.”2 If anything, Lewis was an “emergency” fielder. In Baseball’s Last Dynasty: Charlie Finley’s Oakland A’s, Bruce Markusen recounts a 15-inning loss to Chicago on September 19,

1972, when Lewis, “who almost never played a defensive position,” pinch-ran for first baseman Mike Epstein in the eighth inning and played right field, where he remained until the fourteenth inning.3

It is therefore something of a misrepresentation to say that Washington deprived a “real” ballplayer of his roster spot.4 If Washington replaced anybody, it was Lewis. In signing Washington, Finley decisively (and perhaps misguidedly) embraced the notion of the designated pinch-runner. In switching from a player whose major function was pinch-running to another for whom that was his sole function, Finley merely re- fined a tactic he had already developed with Lewis. In other words, perhaps the real innovation can be found with the use of Lewis in 1973. Finley’s signing of Washington merely built on that precedent.

THE DH REVOLUTION

The institution of the designated-hitter rule also provides some important perspective for evaluating Herb Washington’s 1974 performance. For many (including me) who as baseball fans came of age after the American League had adopted the “designated pinch-hitter” for the 1973 season, the DH is a given, but it should be remembered that the introduction of the DH represented a drastic rules change.5 Other ideas proposed by Finley to spice up the game for the modern era were interleague play, the three-ball walk, and the designated pinch-runner.6 In the version of the DH rule proposed by Finley, a pinch-runner would be used without the replaced player (i.e., the batter) being removed from the game. The designated runner would apparently complement the designated hitter, taking over the baserunning chores if and when the DH reached base. When the final ballot among American League owners featured the DH but not Finley’s “DR,” Finley voted against this diluted version of his original designated-hitter rule.7

As reported in the Philadelphia Inquirer in October 1974, A’s manager Alvin Dark, speaking of Washing- ton’s contribution to the team, advocated use of the designated pinch-runner. “What I’d like to see baseball try next is using a designated runner for the designated hitter. How much longer would a Mickey Mantle have been around with somebody to run for him?”8 In spring training 1975, the year after Washington’s turn as a pinch runner up to four or five times per exhibition game. 9

Against this back drop, the idea of a designated pinch-runner does not sound so crazy anymore. Now that the MLB had taken the radical step to allowing a position player to bat for a pitcher throughout the course of a game, having a player “do the running” for a hitter can be seen to represent a natural extension of that thinking. As with the DH, the objective is the same — to inject more offense into the game. it is logically inconsistent to accept the DH on the one hand, and on the other, to reject the designated pinch-runner as absurd or silly. The two differ only in degree, not kind. If anything, the designated runner is a less extreme modification, as only one aspect of the offen- sive player’s responsibilities has been transferred to another player. Compare this to the designated-hitter rule, which completely eliminated the pitcher as an offensive player, thereby altering the very rhythm of the game.

WHY HERB WASHINGTON?

At first glance, at least, one can readily understand why Finley chose Washington to be his designated pinch-runner. He was fast. Washington was a four- time All-American at Michigan State University, lettering in track and football. Among his other accom- plishments, he set records for both the 50- and 60-yard dash as well as capturing the Big Ten Conference championship for the 100-yard dash in 1970, 1971, and 1972. After seeing Washington compete in an indoor track meet on television, Dark recommended that Finley sign him.10 Such was Washington’s ability that a live tryout on a baseball diamond was deemed un- necessary by Dark; apparently neither Dark nor Finley was concerned that Washington’s only previous base- ball experience was in high school. Dark and Finley weren’t the only ones who saw in Washington’s foot speed the potential to excel at the highest levels of pro- fessional sports. The NFL’s Baltimore Colts and the World Football League’s Toronto Northmen both wanted to sign Washington as a wide receiver.11

THE STATISTICS

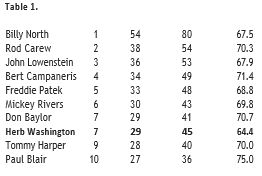

In the 1974 campaign, Washington stole 29 bases in 45 attempts, for a success rate of 64.4 percent. Here’s how Washington’s performance stacks up against those of the other top ten AL base stealers in 1974:

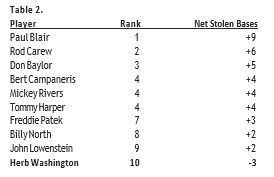

Table 1 shows that, to some extent, Washington’s performance was weaker than those of the other top American League basestealers in 1974. Table 2 corroborates this initial conclusion as it provides a look at Washington’s statistics in the context of the sabermetric of net stolen bases, which gives a more refined and realistic assessment of Washington’s value.12

By this measure, Washington’s baserunning actually did more harm than good, hurting the A’s chances of scoring (and winning). The lost scoring opportunities of the caught-stealing outcomes overshadowed the positive effect of his 29 total stolen bases. It also bears noting that the other top AL base stealers all landed on the plus side of the ledger, representing a net gain to their teams.

Another sabermetric, run-expectancy matrix, confirms what tables 1 and 2 tell us. Using run-expectancy matrix, one can gauge the impact of the attempted stolen base (be it successful or not) on a team’s potential to score runs. Data from Baseball-Prospectus.com show the likelihood of a team scoring during the 1974 season. For example, with a runner on first base and no outs, a team scored, on average, .826833 times in 1974; in contrast, with no runners on base with one out, teams scored only .24098 times.13 When we follow this reasoning, a failed stolen-base attempt decreases a team’s likelihood of scoring by resulting in an out and removing a baserunner; it is the cost of a caught-stealing. In my example, that cost is .585853 runs. 14

To apply run-expectancy matrix to Washington’s 1974 season, I reviewed play-by-play accounts of all A’s games in which Washington attempted a stolen base (available via Retrosheet.org) to determine how his performance affected the A’s opportunities to score runs. The result: Washington cost the A’s 1.1 054 runs over the course of the season. Even more egregiously, during the stretch drive to the end of the regular season in September and October, the cost balloons to 1.79352 runs. Against divisional foes, Washington’s cost is even higher, topping out at 2.18809 runs.15 These numbers become all the more decisive in that, unlike the case of Allan Lewis, Washington’s base- running was the only way he could contribute to the A’s success.16

The data support the notion that there is an art to a base-stealing—something more than raw speed alone is needed for success. If anything, it is this skill as practiced by an experienced player that makes the stolen base attempt an informed risk (notwithstanding the gospel of sabermetrics) as opposed to a “Hail Mary” desperation tactic. It seems safe to assume that Washington’s performance suffered because he failed to augment his natural abilities with baseball knowledge.17 As some of his critics sardonically commented at the time, Washington was operating at a distinct disadvantage as there was no starter’s gun and/or runners blocks on the infield.18 More specifically, even with the tutelage of Los Angeles Dodgers’ basestealing legend Maury Wills19 and teammate Billy North20 (among others), Washington lacked the ability to effectively read pitchers’ pick-off moves and get a good lead or jump.21

THROUGH AN (ALVIN) DARK LENS

With the foregoing in mind, it is interesting to consider Athletics’ manager Alvin Dark’s take on Washington’s season. As noted above, Dark commented to Bill Lyon of the Philadelphia Inquirer that “Herb has won eight games for us by himself since July 1.” Dark then cited two games as proof of his point: “In Minnesota, we put him in and they pitched out three straight times. We went on to a four-run inning. In Anaheim, they were so worried about him that they kept pitching out and we got three runs and won 7—5.”22

Let’s look at each game individually. The second game was the A’s 7—5 win over the California Angels on July 2, 1974. Washington was inserted into the game as a pinch-runner for Joe Rudi with one out in the eighth inning. At the time, Oakland led California 5—3. On the strength of a home run and double by Angel Mangual, the A’s had already knocked starter Frank Tanana from the game. Oakland’s starting pitcher, Ken Holtzman, had been touched up for seven hits through the first five innings but none in the sixth or seventh. As Washington entered the game, the game was close and the outcome still in doubt.

As Dark suggested, the Angels’ worrying about Washington may have resulted in pitcher Skip Lock- wood walking Gene Tenace. But, maybe not. Dark’s thesis is at least somewhat suspect, as Tenace led the American League with 110 bases on balls—many pitchers gave Tenace a free pass without the “distraction” posed by Washington. More tellingly, Tenace fared well against Lockwood over the course of his career, hitting .318 (7 for 22) with two home runs, four RBI, and six walks in total. Given that former A’s manager Dick Williams was at the helm of the Angels and obviously knew the opposition well, it is improbable that Lockwood or California took Washington to seriously. Moreover, Lockwood must have found his groove quickly, as he struck out the next batter, the “hot” Angel Mangual, who had driven in four runs off Tanana. The decisive blow was a single, by pinch-hitter Pat Bourque, that scored Washington and Tenace. (Dark incorrectly recalled that the A’s scored three runs in the inning—they actually scored two). From the play-by-play summary at Retrosheet, it appears that Pat Bourque’s clutch hitting proved decisive and that Washington had precious little to do with the favorable result. So far, Dark is 0—1.

The Minnesota game mentioned by Dark is tougher to pinpoint. A review of Oakland’s 1974 contests against the Twins in Minnesota suggests that Dark was referring to a game on May 21.

In that game, Washington pinch-ran for pinch-hitter Sal Bando in the seventh inning. At the beginning of the inning, the score was tied at 1—1. Oakland scored six times in the inning, with four of these runs coming after Washington had entered the game; thus, when Washington made his appearance, the score was 3—1 in Oakland’s favor. According to Dark’s account,

Minnesota focused their attention on Washington, yielding a walk to Billy North. This put runners on first and second with none out. In this instance, given North’s relatively pedestrian career numbers against relief pitcher Tom Burgmeier (who had relieved starter Joe Decker after the A’s scored on a Gene Tenace home run to start the inning)—0 for 2 up to this point, 3 for 12 (all singles) in his career—Dark’s case for Washington’s effect on the pitcher is at least somewhat stronger. Bert Campaneris then laid down a sacrifice bunt, moving Washington to third and North to second. Burgmeier served up a sacrifice fly to Joe Rudi, scoring Washington, followed by a two-run homer to Reggie Jackson. For the final run of the inning, Pat Bourque doubled home Angel Mangual, who had singled. Again, it is tough to see how Washington affected the outcome beyond possibly contributing to the walk to North. Still, it is worth noting that Burgmeier previously had Joe Rudi’s number. Rudi was 0 for 5 against Burgmeier up to this point, and in his career, he had a paltry two hits off him in 16 at-bats, for a .125 average.

On the other hand, one of those two hits would be a home run. In any event, the real muscle in the inning was provided before and after Washington was on the field. While this is a somewhat closer call than the Angels game, Dark is 0—2.

Puzzlingly, Dark in his comments about Washing- ton omitted several appearances in which Washington did demonstrate value to the team. In the eighth inning of the August 2 game at Chicago, with two outs, Billy North singled off Wilbur Wood and stole second. Sal Bando knocked in North with a single, tying the game at 2—2, prompting White Sox manager Chuck Tanner to summon relief pitcher Terry Forster to stop the bleeding. Washington came into pinch-run for Bando, stealing second. Reggie Jackson then drove home Washington with a single, giving the A’s a lead they would not relinquish.

On August 13 against the Yankees, the A’s led 3—1 going into the bottom of the seventh. Replacing Dal Maxvill (who had drawn a walk), Washington stole second off Doc Medich and Thurman Munson and took third on Munson’s throwing error, one of three errors for Munson on the day. Now, rather than having a man on first with none out, the A’s had a runner on third base. Billy North singled Washington home, giving the A’s a three-run cushion and ending Medich’s day. The A’s scored twice more that inning en route to a 6—1 triumph.

More stunning still is Dark’s claim that Washington “can’t lose us a game” because “he can’t strike out with the bases loaded” or “drop a fly ball.”23 Overall, I counted eleven different situations during the 1974 regular season where Washington’s performance directly hurt the A’s chances of winning a ballgame.24 By way of illustration:

- On May 4 against Cleveland, Washington pinch- ran for Pat Bourque in the seventh Gaylord Perry picked Washington off first, but Washing- ton took second on an error by first baseman John Ellis. Undeterred, Perry picked Washington off second base, ending the inning in a game Cleveland won 8—2.

- On May 7 against Baltimore, Washington pinch- ran for Gene Tenace with one out in the ninth inning and the A’s trailing by six Angel Mangual lined out to second baseman Bobby Grich, who threw to first baseman Enos Cabell to complete the double play and end the ballgame. Where was Washington going? He should have been anchored to first base, as the play was in front of him.

- On August 19 against Milwaukee, Bert Campaneris led off the eighth inning with a Washington was inserted as a pinch-runner and was promptly caught stealing second. The Brewers would prevail 1—0.

- On September 25 against Minnesota, Washington replaced Jesus Alou in the sixth inning and stole second (So far, so good.) Billy North sacrificed Washington to third. Then Twins catcher Phil Roof picked Washington off third, ending the rally and preserving the Twins’ 1—0 lead. The Twins would go on to win the game by that count.

In the Lyon article, Herb Washington takes up his own pro se defense of his baseball credibility, noting that, in a game against Cleveland’s Gaylord Perry, he scored from third base “on a short fly to left.” With a little sleuthing, we know that Washington is speaking of the A’s—Indians game on July 8. With one out in the top of the ninth inning and Cleveland holding a one-run lead, Joe Rudi tripled off Perry. Washington ran for Rudi. A Gene Tenace sacrifice fly scored Washington with the tying run. The A’s went on to win the game in the tenth inning. Washington exacted revenge on Gaylord Perry for his rough treatment about two months earlier.

Here, Washington may have a point. A ball hit to left is tougher to score on than a ball hit to center or right: The throw from left to the third-base side of the plate is shorter. Also relevant is that the left fielder, John Lowenstein, had only an average arm.25 Washington’s speed very well could have made the difference, enabling him to score when someone else might not have.

In sum, however, the statistical evidence clearly suggests that Washington’s stint as a “designated runner” was pure folly. If anything, the A’s succeeded in capturing their third consecutive championship in spite of (not because of) him. Rather than being a “hood ornament”—a thing of aesthetic appeal, which does not affect a vehicle’s performance—Washington impaired the functioning of the “biggest, baddest Blue Odomest Cadillac in the league.”

NOTES

1. See Josh Wilker, “Herb Washington” (7 December 2006), http://cardboardgods.baseballtoaster.com/archives/609836.html (accessed 30 April 2009).

2. Glenn Dickey, Champions: The Story of the First Two Oakland A’s Dynasties—and the Building of the Third (Chicago: Triumph Books, 2002),

3. Bruce Markusen, Baseball’s Last Dynasty—Charlie Finley’s Oakland A’s (Indianapolis: Master’s Press, a division of Howard W. Sams, 1998), 128.

4. Among others, A’s catcher and first baseman Gene Tenace expressed this See Markusen, 287.

5. The Baseball Digest (April 1973) devoted nine pages to “The Designated Pinch-Hitter Rule,” including “Pro” and “Con” columns by Shirley Povich (of the Washington Post ) and Harold Kaese (of the Boston Globe), respectively.

6. Markusen, 17; see also Dickey, 11—12.

7. Markusen, 183—84.

8. Bill Lyon, “They Scoffed but Dark Says Washington Has Won 8 for A’s,” Philadelphia Inquirer, 13 October 1974.

9. “A’s Runner on Spot This Time,” UPI, 20 March 1975 (from National Baseball Hall of Fame, player file for Herb Washington).

10. Dickey, 77

11. If anything, Washington had more recent experience as a football player than as a baseball According to the article “Herb Washington” (November 2003), at Simply Baseball Notebook: Forgotten in Time, http://z.lee28.tripod.com/sbnsforgottenintime/id24.html (accessed 30 April 2009), Washington was a wide receiver on the Michigan State football team in 1971 and 1972, catching one pass for 41 yards

12. For an explanation of “net stolen bases,” see, for instance, Rich Lederer’s article “Net Stolen Bases: Leaders and Laggards” (25 October 2006), Baseball Analysts, http://baseballanalysts.com/archives/2006/10/php (accessed 30 April 2009). In general, the underlying concept is that “caught stealing” must reflect not only that an out was recorded but also that a runner has been removed from the basepaths and a scoring opportunity eliminated. As Retrosheet categorizes being picked off as a form of caught stealing, I used the following formula to derive net stolen bases: Net stolen bases = Stolen bases − (2 x caught stealing).

13. See Baseball Prospectus, baseballprospectus.com/statistics/sortable/index.php?cid=148993 (accessed 30 April 2009). For an introduction to run expectancy matrix (as well as a more general application of sabrmetrics to stolen base attempts), see “Thou Shalt Not Steal” (14 January 2009), Backell’s Big Blog of Bodacious Brewing Brainstorms, www.sportingnews.com/blog/backell/130093 (accessed 4 May 2009).

14. When considered in the context of run-expectancy matrix, the stolen-base attempt can be fairly characterized as something of a The cost of failure (an out and the loss of a baserunner) outstrips the potential benefits (moving a base runner into scoring position without sacrificing an out). To illustrate using the above example: If the runner had stolen second base with no outs, a team’s likelihood of scoring would rise only to 1.07689. This represents a “gain” of .25006 runs, as compared to the possible cost of .585853 runs.

15. Still, this figure is something of a restatement of the immediately pre- ceding calculation, as from September 2 through the end of the 1974 season the A’s played against only teams in the AL

16. As Sal Bando pointedly commented, although Lewis’s talent may have been negligible, he “could play a position here or there if you needed ” See Markusen, 209.

17. Markusen recounts an early regular-season game where Washington asked his manager whether he should steal second base—even though the base was occupied at the Markusen, 294.

18. See article “Finley Worships Speedsters,” 13 April 1974 (from National Baseball Hall of Fame, player file for Herb Washington).

19. Markusen, 286—87.

20. See article “A’s Washington Is Gaining Respect of His Teammates,” 18 August 1974 (from National Baseball Hall of Fame, player file for Herb Washington).

21. As Washington was a true neophyte, the issue of the comparative merit of jump versus lead is moot

22. See n. 8

23. See 7. For absolute irony, the date of the Lyon article coincided with that of Washington’s ignominious performance in the ninth inning of Game 2 of the 1974 World Series, when he was picked off first base by Los Angeles Dodgers reliever Mike Marshall. The Dodgers won Game 2 and evened the series at one game apiece.

24. I admit to a significant amount of subjectivity here, especially as I relied on the play-by-play feature of Retrosheet. In most instances, Washing- ton’s successes and failures on the basepaths did not affect the outcome of the game, and his mistakes were “harmless ” For example, in the July 30 game against Texas, Washington pinch-ran for Pat Bourque and stole second base in the sixth inning. As the A’s held an 8—2 lead at the time and would eventually win 11—3, it is clear that Washington’s stolen base had no effect on the outcome of the game.

25. In 1974, Lowenstein had 5 assists as a left fielder, compared to 13 for Lou Piniella and 11 for Carlos