Hot Streaks, Screaming Grounders, and War: Conceptual Metaphors in Baseball

This article was written by Daniel Rousseau

This article was published in Fall 2019 Baseball Research Journal

Until my freshman year of college, the only books I’d read cover-to-cover were baseball almanacs and biographies of early and mid-twentieth century baseball players like Ed Delahanty and Satchel Paige. Throughout grade school, I spent my evenings flipping through onionskin pages full of baseball stats or studying the backs of baseball cards. An Indians fan, I would use historic home run and strikeout totals along with batting and earned run averages to construct imagined scenes from Cleveland baseball history.

In the second grade, I developed a fondness for Hall of Fame pitcher Addie Joss. He played from 1902 to 1910. His career was cut short by meningitis. There was no picture of him in my almanac, but I used his 1.89 career ERA and .968 WHIP to construct an image in my head of a sturdy and precise man — stirrups even and pressed, face placid and clean. Only a wild pitcher, I had thought, would grow an unruly beard. Indeed, if Joss were the most precise pitcher ever, he would have no facial hair. I wouldn’t know for sure what his face looked like until I was in middle school when I encountered a Joss tobacco card at a collector’s convention in Chicago. In the image on the card, he was mostly as I’d imagined: straight-faced with a popped jersey collar. But I did not expect his hair parted down the middle, his bangs curled and waxed like some dorky pre-war actuary.

Each time I attend a baseball card show, I’m introduced to another of my hero’s faces and can’t help but imagine that player at work. In my imagined scenes, actions and dialogue are derived from a unique baseball vocabulary: bases load like guns, changeups fall off tables, and frozen ropes earn doubles. This vocabulary has influenced the way I organize and retrieve my memories. In my brain, I file cable news clips of war next to Josh Hamilton’s 2008 Home Run Derby performance, tie my two weeks in the Ecuadorian jungle to Rick Ankiel’s wild fastball, and place my father’s death beside the 1997 World Series, which the Cleveland Indians lost. When I study baseball-related language, I am studying myself — my history, assumptions, and proximity to the world. Language and cognition are inseparable, and so our passions impact our perceptions, thought organizations, and communications.

In their book Metaphors We Live By, cognitive linguists George Lakoff and Mark Johnson claim that “the essence of metaphor is understanding and experiencing one kind of a thing in terms of another.”1 We cannot make sense of our complex inner and outer worlds without conceptual metaphors, through which we decipher and describe non-tactile or ambiguous concepts by comparing them to concrete objects and experiences. Metaphors are not merely “characteristic of language alone,” but “pervasive in everyday life…in thought and action.”2 To strip our lives of metaphor is to live in a single dimension, to know nothing but unnamed, immediate sensations. Metaphors allow us to name and play in confounding depths — everywhere from our psyches to the cosmos — which is, I think, to be human.

Here, I’ll examine orientational, ontological, and structural metaphors used to describe baseball games. As I do, I hope some of the core assumptions and perceptions that are common amongst baseball fans, and perhaps humanity as a whole, become more evident. Most importantly, I hope this basic survey will bolster my — and hopefully my readers’ — ability to intentionally and effectively recognize and construct metaphors, then employ them in communication, to better describe the human experience.

I live vicariously through Dodgers pitcher Clayton Kershaw. We’re about the same age, and both have four-year-old daughters. But Clayton is five inches taller than I, left-handed, and induces major-league whiffs with a swooping, 88-mph slider. At this point in my life, my fastball peaks at 73 — that according to a carnival speed gun. In an alternate reality, I sometimes think, there is a tall, athletic version of myself who throws physics-bending curveballs. I watch every Kershaw start on television. He is in California while I am in Philadelphia. Our time zone difference means that I will likely stay up past midnight once every five days during the baseball season. My wife heads to bed without me on Kershaw nights.

I live vicariously through Dodgers pitcher Clayton Kershaw. We’re about the same age, and both have four-year-old daughters. But Clayton is five inches taller than I, left-handed, and induces major-league whiffs with a swooping, 88-mph slider. At this point in my life, my fastball peaks at 73 — that according to a carnival speed gun. In an alternate reality, I sometimes think, there is a tall, athletic version of myself who throws physics-bending curveballs. I watch every Kershaw start on television. He is in California while I am in Philadelphia. Our time zone difference means that I will likely stay up past midnight once every five days during the baseball season. My wife heads to bed without me on Kershaw nights.

On June 18, 2014, Clayton Kershaw no-hit the Colorado Rockies. Baseball wordsmith Vin Scully provided the color commentary. Scully began his career as a radio announcer. His descriptions of that game were so vivid that pictures weren’t necessary. The baseball, according to Scully, “dips” and “drifts,” gets “punched” and “speared.” In the third inning, a Rockies batter hit a “soft line drive.” Scully, always concerned about his words’ clarity, defined his terms, “The use of the word line-drive is describing the trajectory.” In the eighth inning, when it seemed the Rockies might not get a hit, the camera panned to Kershaw’s wife. Scully, speaking like a proud family member, noted, “There’s Ellen, applauding her hubby.” In contrast to the elated Dodgers, the Rockies looked dejected. Scully used a refrain to describe struck-out Rockies: “Down he goes.” “Down he goes.” “Down he goes.” I imagine the Colorado hitters knew their doom was inevitable, like characters in Vonnegut’s Slaughterhouse Five: “So it goes.” “So it goes.” “Down he goes.” Here, I am concerned about that metaphorical downward movement toward outs.

According to Lakoff and Johnson, many conceptual metaphors are the result of our spatial orientation. Indeed, they “arise from the fact that we have bodies of the sort that we have and that they function as they do in our physical world.”3 Through orientational metaphors, we “organize a whole system of concepts with respect to another.” That is, we make sense of abstract ideas by way of physical perceptions, “up-down, in-out, front-back, on-off, deep-shallow, central-peripheral.”4 We often describe abstract concepts, such as emotions, as physical entities within our perceived spaces: I am feeling down; Things are looking up; Her spirits are high.

Based on linguist William Nagy’s research (1974), Lakoff and Johnson suggest nine spatial concepts which drive orientational metaphors:

- “Happy is up; sad is down.”

- “Conscious is up; unconscious is down.”

- “Health and life are up; sickness and death are down.”

- “Having control or force is up; being subjected to control or force is down.”

- “More is up; less is down.”

- “Foreseeable future events are up (and ahead).”

- “High status is up; low status is down.”

- “Virtue is up; depravity is down.”

- “Rational is up; emotional is down.”5

As these orientational concepts are dependent upon subjects’ immediate environments, they will not be uniform across all cultures. However, most of these concepts appear as driving forces in baseball descriptions.

In his essay collection The Summer Game, Roger Angell — a J.G. Taylor Spink Award winner and long-time New Yorker fiction editor — describes baseball in the 1960s. His book, like the sport during that decade, is dominated by images of the Yankees, Dodgers, Giants, and Cardinals — and hopeful considerations of the pitiful, fledgling Mets. Occasionally, Angell constructs essays by watching games on television, but most of the time, he writes about his first-hand experience as a fan at the ballpark.

Of a 1962 playoff game between the Giants and Dodgers, Angell writes, “One out of every three or four [Dodgers fans] carries a transistor radio in order to be told what he is seeing, and the din from these is so loud in the stands that every spectator can hear the voice of Vin Scully.”6 Like many of my own potent baseball memories, those fans’ recollections — including Angell’s — are forever linked to Scully’s voice, his turns of phrase, his metaphors.

Of a 1962 playoff game between the Giants and Dodgers, Angell writes, “One out of every three or four [Dodgers fans] carries a transistor radio in order to be told what he is seeing, and the din from these is so loud in the stands that every spectator can hear the voice of Vin Scully.”6 Like many of my own potent baseball memories, those fans’ recollections — including Angell’s — are forever linked to Scully’s voice, his turns of phrase, his metaphors.

Using language similar to Scully’s refrain from that 2014 Kershaw no-hitter — “Down he goes” — Angell describes an important moment from the ’62 series: “[Maury] Wills stole second, and the Giants’ catcher, in attempting to cut him down, relayed the ball to center field and to the possessor of the best arm on the club, Willie Mays, who then cut down Wills at third.”7 The speedy Maury Wills, like a tree chopped down and removed from the forest, was, when tagged out, removed from the field of play. If health and life are up and sickness and death are down, then we might conclude that the base paths on a baseball field are reserved for wellness and vitality; they are up. As such, it is common for fans, commentators, and writers to describe winning teams as riding high and losers as fallen.

Perhaps some people are attracted to baseball because it is a quick and obvious representation of their struggle to remain upright. We are all bound to the world by gravity and celebrate many human achievements which work against it: first steps and bike rides, stolen bases and home runs. Orientational metaphors, then, which are rooted in near-universal physical perceptions or at least common language related to those perceptions, are strong connecting points between the orator or writer and the audience.

In 1963, the New York Mets lost 111 games. The previous year they’d lost a historic 120. Still, Roger Angell made his way to the Polo Grounds, where he and a boisterous crowd rooted for that lovable but struggling team. Angell writes about those Mets:

Last year when the team trailed the entire league in batting…its team average was .240. So far this year, the Mets are batting .215, and a good many of the regulars display all the painful symptoms of batters in the grip of a long slump — not swinging at first pitches, taking called third strikes.8

Slumps, it seems, are heavy diseases which attach themselves to baseball players, then pull them downward toward outs. On the literal surface, the Mets may have looked strong and confident, but beneath a metaphorical lens, they might have appeared hunched over, straining to stand — let alone hit — in the batter’s box.

Angell suggests that if the Mets’ offensive woes continue, their manager “will be forced to insert any faintly warm bat into the lineup, even at the price of weakening his frail defense.”9 We understand temperature in up-down terms; it rises and falls. Cold is, perhaps, closer to rigidness or death than heat, or at least away from free movement and vitality; it is down. In baseball, a players’ metaphorical temperature is equivalent to their readiness to enter the game and their likelihood to remain upright, which is to help their team win. Players who have consistently performed at an elite level are often described as hot. Struggling players are cold.

While hot-cold metaphors are grounded in our spatial orientations, they also draw from our direct experiences with objects: snow, campfires, coffee, etc. Lakoff and Johnson call such metaphors “ontological.” Through ontological metaphors, we understand abstract concepts as concrete entities. Ontological metaphors might be richer or more specific than orientational metaphors:

One can only do so much with orientation. Our experience of physical objects and substances provides further basis for understanding…Once we can identify our experiences as entities or substances, we can refer to them, categorize them, group them, and quantify them — and, by this means, reason about them.10

Through ontological metaphors, we might understand a struggling baseball team as more than simply fallen, but rather a defective machine — a complex physical entity. One might describe those 1963 Mets as rusty or not firing on all cylinders. Roger Angell describes that team’s manager as a novice mechanic whose “Tinkering [of the lineup] can lead to the sort of landslide that carried away the Citadel last year.”11 As machines are full of unique parts and movements, the ontological metaphors built from them — by way of direct observation or experience — might be intricate and action-packed.

If people construct ontological metaphors through specific, past physical experiences, how might they impact our physical states when called upon in the present? Do fans feel literally cold when their favorite player strikes out, stuck in a frigid slump? In a close game, do fans literally feel hotter when they see their All-Star closer warming up in the bullpen?

In their paper “Cold and Lonely: Does Social Exclusion Literally Feel Cold?” University of Toronto social psychologists Chen-Bo Zhong and Geoffrey J. Leonardelli write, “Metaphors such as icy stare and cold reception are not to be taken literally and certainly do not imply reduced temperature. Two experiments, however, revealed that social exclusion literally feels cold.”12 In one experiment, Zhong and Leonardelli asked sixty-five undergraduate students to recall “a situation in which they felt socially excluded or included.”13 Then, at the request of a supposed maintenance staff member, those students estimated the current room temperature. Consistently, students who had been asked to recall memories of social exclusion estimated lower room temperatures. For those students, social exclusion felt cold. Therefore, metaphorical concepts primed literal, physical sensations. Commenting on their experiment’s results, Zhong and Leonardelli note,

[These Findings] highlight the idea that metaphors are not just linguistic elements that people use to communicate; metaphors are fundamental vessels through which people understand and experience the world around them…It is possible that people use coldness to describe social interaction patterns partly because they observe, at an abstract level, that the experience of coldness and the experience of social rejection coincide.14

Metaphors are bridges by which people connect abstract concepts to literal, physical perceptions. For example, uncertainty is chilling, ambitious plans are lofty, and depression is dim. In this way, abstract and concrete concepts and their connecting metaphors are tied together in our brains. When someone entertains a metaphor, they may also experience any of the abstract or concrete concepts that metaphor was initially built to bridge.

The metaphors that Vin Scully and Roger Angell use to construct images of baseball games in their listeners’ or readers’ minds affect their psychological, emotional, and physical states. I imagine if I were a Rockies fan watching that Kershaw no-hitter on mute, in the absence of Scully’s voice, the images on the screen would frustrate me. Perhaps I’d curse at Colorado pitcher Jorge De La Rosa after he allowed five runs in the third inning. Maybe I’d pound my right fist on my knee when Rockies catcher Wilin Rosario struck out for the third time. But if I turned on the volume and let Scully tell me what I was seeing, he might lull me from mere frustration into depression. Maybe after I heard his refrain, “Down he goes,” I’d hang my head, then hunch my back. Perhaps if he said that the Rockies’ hitters looked “scared and lonely” at the plate, I’d also feel alone, and possibly cold. If Scully called the Rockies’ offense broken, I might be moved to sadness, as I was in the third grade when my dog destroyed my Sammy Sosa rookie card, chewed beyond repair.

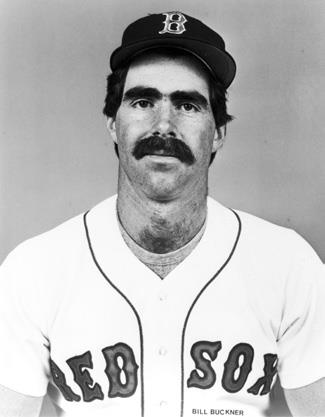

One of the most iconic calls of Scully’s career came in Game Six of the 1986 World Series. The Red Sox led the Mets three games to two and were on the verge of their first championship since 1918. In the bottom of the 10th inning of the sixth game, with the score tied 5-5 and Mets infielder Ray Knight on third, Mookie Wilson, a speedy bean-pole-of-a-man, hit a “Little roller up along first.” Before Wilson’s hit, Red Sox first basemen Bill Buckner had positioned himself 20 feet from the bag. As Wilson swung, Buckner shuffled five steps to his left and crouched to receive the ball. At that time, Buckner — strong, handsome, and mustached — was one of Boston’s stars. He’d won a batting title in 1980 and twice led the league in doubles. But at that point in his career, Buckner was not sure-handed and he failed to field Wilson’s grounder. Vin Scully yelled, “Behind the bag! It gets through Buckner. Here comes Knight, and the Mets win it!”

One of the most iconic calls of Scully’s career came in Game Six of the 1986 World Series. The Red Sox led the Mets three games to two and were on the verge of their first championship since 1918. In the bottom of the 10th inning of the sixth game, with the score tied 5-5 and Mets infielder Ray Knight on third, Mookie Wilson, a speedy bean-pole-of-a-man, hit a “Little roller up along first.” Before Wilson’s hit, Red Sox first basemen Bill Buckner had positioned himself 20 feet from the bag. As Wilson swung, Buckner shuffled five steps to his left and crouched to receive the ball. At that time, Buckner — strong, handsome, and mustached — was one of Boston’s stars. He’d won a batting title in 1980 and twice led the league in doubles. But at that point in his career, Buckner was not sure-handed and he failed to field Wilson’s grounder. Vin Scully yelled, “Behind the bag! It gets through Buckner. Here comes Knight, and the Mets win it!”

In the months following his error, Buckner would receive death threats from crazed Red Sox fans who blamed him for that World Series loss. His name would become synonymous with failure. But in that moment, Scully did not say “Buckner missed it” or “Buckner made an error,” but rather that the ball went “through” Buckner. Scully deemed the baseball, not a player, the main actor.

Often in baseball commentary, the ball is described as a creature. After a player swings at and misses a 95-mph fastball, an announcer might say that the ball ate the batter up. Or if a batter pushes a perfect bunt down the third-base line, so the ball rolls to a stop before the catcher or third baseman can field it cleanly, a writer may explain that the ball died on the field.

Sometimes, baseballs are described like people which dance, race, baffle, and hum. According to Lakoff and Johnson, such attributions “allow[s] us to comprehend a wide variety of experiences with nonhuman entities in terms of human motivations, characteristics, and activities.”15 Roger Angell personifies the baseball in his description of a 1968 matchup between the Red Sox and White Sox. In the third inning, Chicago’s left fielder Tommy Davis hit “a two-base screamer just inside the bag at third.”16 Maybe Davis swung so hard, made such true contact, that the baseball did not merely hiss as it usually does when rushing through wind, but yelled. Imagine standing at a street corner, an angry man shouting obscenities as he runs in your direction. Can you blame Boston’s third baseman for stepping to the side of that screaming grounder, letting it pass?

Perhaps if baseballs always moved as expected, and weren’t consistently fooling or injuring players, people might see them as fair and honest characters which, when batted, deserve secure send-offs rather than harmful hits. However, baseballs, so far as most baseball people know them, are crafty and unpredictable, worthy of punishment. Broadcasters happily describe batted balls as smacked, crushed, walloped, destroyed, slapped, rapped, struck, banged, pounded, cracked, punched, swatted, belted, and shot. Baseball language is often violent.

Radio commentator John Sterling creates a unique home run call for every Yankee. He often uses alliteration and rhymes. In the past, he called each Derek Jeter home run a “Jeter Jolt,” and with every Chris Carter blast he exclaimed, “Carter hits it harder!” Often Sterling utilizes battle-like phrases: “Bernie goes boom!” “Kelly killed it!” “It’s a nuke from Youk!” “It’s an A-bomb for A-Rod!”

On March 29, 2018, when power-hitting right fielder Giancarlo Stanton hit his first home run as a Yankee, John Sterling exclaimed, “It is gone! In his first Yankee at bat! Giancarlo, non si puó stoparlo! (Giancarlo can’t be stopped!) It is a Stantonian home run. A two-run blast.” Many Yankees fans did not like some of ways Sterling had described that home run. On social media, they questioned Sterling’s poor Italian and dismissed his use of that added suffix in “Stanton-ian.” “Ruthian” is already a common word in the Yankee vernacular, and any comparison between Stanton and Ruth might be blasphemous in the Bronx. But nobody challenged Sterling’s use of the word “blast.” Few people ever question his war words.

Maybe John Sterling, like many baseball fans, not only thought that Stanton’s home run ball resembled a soaring weapon or that the slugger’s buttoned uniform looked like battledress, but has conceptualized the entire sport as war. Maybe he’s mentally organized baseball atop an existing schema of battle, and so he cannot separate the motives and strategies of literal war from his metaphorical understanding of the game. Perhaps a single structural metaphor, baseball as war, drives most baseball commentary.

While orientational metaphors help us to understand abstract concepts in broad physical terms, they “are not,” write Lakoff and Johnson, “in themselves very rich.”17 And though we might personify inanimate objects through ontological metaphors — know ourselves and the world in more complex terms than up and down or in and out — they are limited by their necessary relationship to tangible items. We might only comprehend our inner and outer worlds as specific intangible systems through structural metaphors. Of all conceptual metaphor types,

Structural metaphors…provide the richest source of elaboration. Structural metaphors allow us to do much more than just orient concepts, refer to them, quantify them, etc., as we do with simple orientational and ontological metaphors; they allow us, in addition, to use one highly structured and clearly delineated concept to structure another.18

Perhaps the most common example of a structural metaphor is rational argument as war. Like all animals, humans “fight to get what they want.”19 However, unlike the rest of the animal kingdom, we have instituted rational parameters around conflict and developed “sophisticated techniques for getting our way.”20 We not only participate in reckless fights but structured battles, not only physical altercations but rhetorical situations. In verbal arguments,

Each sees himself as having something to win and something to lose, territory to establish and territory to defend. In a no-holds-barred argument, you attack, defend, counterattack, etc., using whatever verbal means you have at your disposal — intimidation, threat, invoking authority, insult, belittling, challenging authority, evading issues, bargaining, flattering, and even giving “rational reasons.”21

We spend much of our social lives in arguments, many of them subtle and nuanced. Our default rhetorical moves in those arguments are often combat-like, designed to maneuver metaphorical battle flags toward us. As protective animals in a society often framed by war, we might perceive any two-sided contest as a battle, and so, as with rational argument, we may conceptualize and describe baseball as war.

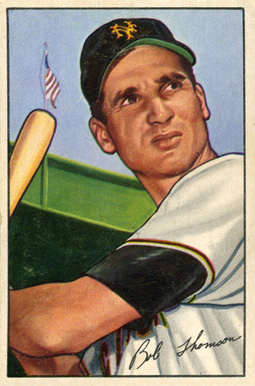

In 1951, New York Giants utility player Bobby Thomson hit a walk-off home run to win the National League pennant, sending his team to the World Series. The following day, the New York Daily News dubbed Thomson’s home run “The Shot Heard ‘Round the Baseball World,” a play on Ralph Waldo Emerson’s 1837 “Concord Hymn,” written to commemorate the beginning of the Revolutionary War. In that poem, Emerson writes, “Here once the embattled farmers stood/And fired the shot heard round the world.”22

In 1951, New York Giants utility player Bobby Thomson hit a walk-off home run to win the National League pennant, sending his team to the World Series. The following day, the New York Daily News dubbed Thomson’s home run “The Shot Heard ‘Round the Baseball World,” a play on Ralph Waldo Emerson’s 1837 “Concord Hymn,” written to commemorate the beginning of the Revolutionary War. In that poem, Emerson writes, “Here once the embattled farmers stood/And fired the shot heard round the world.”22

In the prologue to his novel Underworld, Don DeLillo imagines J. Edgar Hoover at the Polo Grounds the day Bobby Thomson hit that famed “shot.” In DeLillo’s fictionalized account, just before the Thomson blast, Hoover learns of a secret Russian atomic test, the deployment of an enemy “instrument of conflict…a red bomb that spouts a great white cloud like some thunder god of ancient Eurasia.”23 Hoover is not concerned with the outcome of the baseball game, but “the way our allies one by one will receive the news of the Soviet Bomb.”24 After Thomson’s hit soars into the stands beyond Dodgers left fielder Andy Pafko, the Giants fans and players erupt into victorious mayhem. People toss thousands of newspaper clippings, receipts, and ripped magazine pages into the air. Paper rains over J. Edgar Hoover like confetti. Here, he stands at the intersection of the literal and metaphorical, between the tangible by-products of victory — streamers and joyous chants — and the complex intangibles which often drive war strategy and baseball language: morality, justice, purpose.

Fans who conceptualize baseball as war, their team’s seasons as moral and just conquests, might employ battle terms in discussions about gameplay: Koufax has coerced ten players to swing at his curveball; The manager should have deployed his closer earlier; Henderson evaded the tag at third; The Cubs pitching staff lacks firepower; Hershiser looks tired but will not surrender; That Cabrera double might spark a breakthrough; Griffey is patrolling center field; Acuña was plunked, but took the high ground and did not rush the mound.

The baseball as war metaphor is compelling, but we might not only know the game that way. The sport is many things to many people. To some, baseball is a meticulous, practiced craft performed through improvisation, and so it is jazz. To others, baseball is athletic leaps performed by sculpted men in matching costumes, a ballet. Still, others may know the game as a matrix where player actions resemble numbers which collide and change and reveal or echo mathematical truths. Perhaps the depth and breadth of our passions apart from baseball are among the few limits on our metaphorical conceptions of it.

In her essay “I Remember, I Remember,” poet and essayist Mary Ruefle writes about making a metaphor:

I remember — I must have been eight or nine — wandering out to the ungrassed backyard of our newly constructed suburban house and seeing that the earth was dry and cracked in irregular squares and other shapes, and I felt I was looking at a map and I was completely overcome by this description, my first experience of making a metaphor, and I felt weird and shaky and went inside and wrote it down: the cracked earth is a map.25

Humans are miraculous metaphor-making machines. Our brains are full of beautiful, complex connections between formless mysteries and tactile or structured elements. We construct most metaphors unconsciously. But some people, like Ruefle, can make rich metaphors actively. Active metaphor construction is a practiced craft, honed through repeated and deep deliberations of undefined concepts, and perhaps bolstered by a basic understanding of how humans conceptualize their worlds: orientationally, ontologically, structurally.

When we invent metaphors, we satisfy a primal human urge to decipher and organize thought and experience. Mary Ruefle explains how she felt after constructing that first metaphor, “It was an enormous ever-expanding room of a moment, a chunk of time that has expanded ever since and that my whole life keeps fitting into.”26 I imagine, with each new metaphor I construct, fractal-like synapse paths grow in my brain, connecting emotions, senses, and objects in new, unique ways.

Recently, my mother retired and moved in with my family. She brought boxes full of my childhood things with her: baseball cards, model cars, and wide-ruled notebooks. I did not read or write many stories as a child. My early notebooks mostly contain black and white drawings. On the first page of my fifth-grade notebook, I drew Bob Feller mid-pitch, his left toe pointed high in the air. On the second page, I drew a cartoon of Mark McGwire flexing, the word slugger printed across his chest. On the fourth page, I drew a hodge-podge of baseball players, only identifiable by the last names scrawled above their heads: Thomas, Vizquel, Griffey, Belle, Justice, Maddux, Bonds. Below that player lineup, I identified an important metaphor that many of my experiences keep “fitting into”: baseball is my life.

DANIEL ROUSSEAU is a Philadelphia-based writer. His work has appeared in Cimarron Review, The Briar Cliff Review, and Salon, among others. He has been a finalist for the Frank McCourt Memoir Prize, and his essay “Retrieving Charlie Gehringer” received a notable citation in Best American Essays 2018.

Sources

Angell, Roger. The Summer Game. Lincoln: University of Nebraska Press, 2004.

Delillo, Don. Underworld. New York: Scribner, 1997.

Emerson, Ralph Waldo. “Concord Hymn by Ralph Waldo Emerson.” Poetry Foundation. https://www.poetryfoundation.org/poems/45870/concord-hymn.

Lakoff, George, and Mark Johnson. Metaphors We Live By. Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 2017.

Ruefle, Mary. “I Remember, I Remember.” Poetry Foundation, July 2, 2012. https://www.poetryfoundation.org/poetrymagazine/articles/69829/i-remember-i-remember

Zhong, Chen-Bo, and Geoffrey J. Leonardelli. “Cold and Lonely: Does Social Exclusion Literally Feel Cold?” Psychological Science 19, no. 9 (2009): 838-842.

Notes

1 George Lakoff and Mark Johnson, Metaphors We Live By (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 2003), 5.

2 Lakoff and Johnson, Metaphors We Live By, 3.

3 Lakoff and Johnson, Metaphors We Live By, 14.

4 Lakoff and Johnson, Metaphors We Live By.

5 Lakoff and Johnson, Metaphors We Live By, 15-17.

6 Roger Angell, The Summer Game (Lincoln: University of Nebraska Press, 2004), 72.

7 Angell, The Summer Game.

8 Angell, The Summer Game.

9 Angell, The Summer Game.

10 Lakoff and Johnson, Metaphors We Live By, 25.

11 Angell, The Summer Game, 50.

12 Chen-Bo Zhong and Geoffry J. Leonardelli, “Cold and Lonely: Does Social Exclusion Literally Feel Cold?” Psychological Science 19, no.9 (2008): 838.

13 Zhong and Leonardelli, 839.

14 Zhong and Leonardelli, 840.

15 Lakoff and Johnson, Metaphors We Live By, 33.

16 Angell, The Summer Game, 21.

17 Lakoff and Johnson, Metaphors We Live By, 61.

18 Lakoff and Johnson, Metaphors We Live By, 61.

19 Lakoff and Johnson, Metaphors We Live By, 62.

20 Lakoff and Johnson, Metaphors We Live By, 62.

21 Lakoff and Johnson, Metaphors We Live By, 62.

22 Ralph Waldo Emerson, “Concord Hymn by Ralph Waldo Emerson,” Poetry Foundation, https://www.poetryfoundation.org/poems/45870/concord-hymn.

23 Don DeLillo, Underworld (New York: Scribner, 1997), 23.

24 DeLillo, Underworld, 30.

25 Mary Ruefle, “I Remember, I Remember,” Poetry Foundation, July 2, 2012, https://www.poetryfoundation.org/poetrymagazine/articles/69829/i-remember-i-remember.

26 Ruefle.