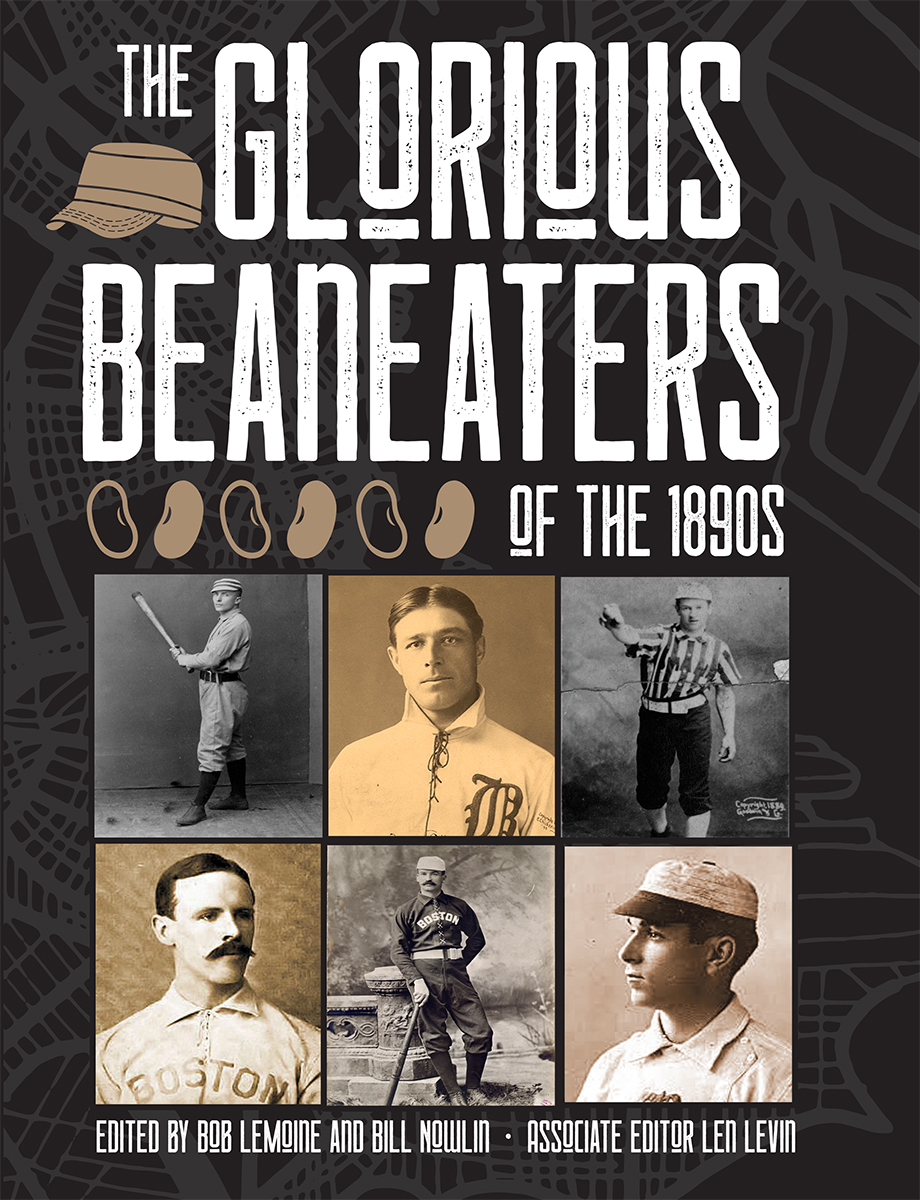

How Bostonians Became the Beaneaters

This article was written by Mark Souder

This article was published in 1890s Boston Beaneaters essays

Most baseball fans, and nonfans for that matter, would consider Beaneaters to be among the most interesting major-league team nicknames with longevity (i.e., multiyear usage as opposed to short-term fad). In 1883 the Boston NL team became unofficially recognized by various sportswriters as the Beaneaters, though like most major-league teams they were generally referred to by their city name.

Most baseball fans, and nonfans for that matter, would consider Beaneaters to be among the most interesting major-league team nicknames with longevity (i.e., multiyear usage as opposed to short-term fad). In 1883 the Boston NL team became unofficially recognized by various sportswriters as the Beaneaters, though like most major-league teams they were generally referred to by their city name.

The Red Stockings (i.e., Red Sox, Reds) nickname began in professional baseball in Cincinnati. The Braves nickname was a gift to Boston by New York City Tammany Boss Charles Murphy’s business partner and close ally James Gaffney when he bought the Boston NL team. Unlike the other nicknames, Beaneaters is the truly original Boston baseball nickname because Boston and beans have long been associated. The nickname evolved informally because Boston was universally recognized as Beantown.1 Eventually the city promoted itself with assorted symbols of the bean. In fact, they still do as is symbolized by everything from Boston Hard Rock Café beanpot pins to the annual Boston Beanpot Tournament featuring four local college hockey teams.

To understand why the Bostons became the Beaneaters requires some understanding of what is called “bean migration” and how Boston became associated with beans. More specifically, how Boston baked beans became the most geographically identified beans in the world, rivaled only by the lima bean.

Why Are Bostonians Associated with Beans?

Boston is not the home of beans in the Americas. Bean migration is more about when various beans are noted in print than their actual appearance on earth. In 1551 the term “kidney bean” was first used in England so the English bean wouldn’t be confused with common beans from the Americas, such as the lima bean, which migrated into the American colonies from what is believed to be Peru through Guatemalan distributors.2

When the first European settlers migrated to the Boston region, the beans had long ago arrived. While beans were not noted in the first “thanksgiving” feast between the natives and the Pilgrims (only venison, fowl, and maize are named), there is little doubt that beans were served, since it was a common staple that accompanied maize in the natives’ diet.3Beans often get shortchanged in publicity. The Pilgrims soon adopted beans and beanpots as their own, largely for spiritual reasons: They could be prepared on Saturday so cooking did not have be done on their Sabbath Day.

While beans were in Boston before it was Boston, they were everywhere else as well. So how did beans become a worldwide association with the city of Boston? While there were a number of villages named Beantown, the Beantown most often referred to in the nineteenth century was in Maryland. But by the 1880s Boston was referred to as Beantown. Nearby Beverly complained about being neglected since it had the largest beanpot manufacturer, and occasionally had been referred to as the city most associated with beans such as in an 1839 New Orleans Picayune, article4, but it was Boston that had a bean style named after it: Boston baked beans.

Before focusing on how Boston became the bean capital and why in 1883 the media began calling the baseball team the Beaneaters, a bit of bean history further explains an important role of Boston in American history and why Americans across the land easily associated Boston with baked beans. In marketing terms, it is cognitive resonance. In other words, people already associated beans with Boston, thus Boston (including baseball) marketed the term successfully because it already resonated with a logical association.

First one must understand what Boston baked beans are. The essential characteristics of baked beans are white beans, which are baked, including bits of pork, and then are cooked in a sauce of tomato, molasses, and corn syrup – or even maple syrup in the Quebec version. The cooking in the sauce turns the white beans brown. The original Boston version utilized molasses, as did most variations in New England.

While this explains the product, since it was widely produced in New England and Canada, how did Boston become the original focus of the baked beans, so associated with baked beans internationally that Boston baked beans are still a common term regardless of their origin? The simple answer has two parts: Both Boston’s port and the related rise of manufacturing, both for canned goods and pottery production.

Long-distance travelers needed to preserve food. France is notable in bean history, as in most gastronomic history. Napoleon is credited with stating that “an army marches on its stomach,” though it is attributed by some to Frederick the Great.5

What is true for armies, who are generally on land, is even truer for navies. Boston was a vital port in early America, home of the best harbor closest to England. Its importance is illustrated by the frigate Constitution, known as Old Ironsides, the the oldest commissioned naval vessel still afloat, and is preserved in Boston at the old Charlestown Navy Yard.

Beans were a poor man’s protein substitute for meat. Meat was often “salt pork” and “dried beef” (“salt beef”). Boston, as the heart of New England, thus became the center for beans as well as cod and dried beef, which could be preserved for seafaring men. New England was also America’s original manufacturing center to a large degree because of Boston and other regional ports such as Newport, so materials to store the items as well as cook them also centered on Boston.

The small white beans called haricot beans are the preferred bean for Boston baked beans, though other white beans can be used. Haricot beans are generally referred to as navy beans because of their ubiquitous use by the navy.

Molasses imported to Boston from the Caribbean was the key ingredient that improved the taste of the canned navy beans. Molasses was heavily used for rum, the favored drink of the era. Samuel Adams was an importer, but despite the eponymous beer, it is not clear that Adams brewed beer or rum. But he likely imported molasses and certainly imported malt. Sam Adams was at least a “maltster.”6

But the real breakthrough was in canning. Boston canneries were the first to invent a can that preserved the beans. (The beanpots were not hard to make.) The key canning firm was Henry Mayo & Co. of Boston, which was the first producer of baked beans in cans (notwithstanding Van Camp’s claim).

The company experienced a setback when, after receiving the silver medal for the best baked beans in the world at the Paris World’s Fair in 1878, Henry Mayo was awarded a contract from the French government for 100,000 dozen cases. The company attempted to fill it, but the French government canceled the contract and Henry Mayo & Co. was awash in canned goods. It began national advertising, which greatly advanced the close tie of Boston to baked beans, but the firm went belly-up six years later.7

The world’s first distinctively marine exhibition, the International Maritime Exhibition, was held in Boston in 1889-90. One of the exhibits was by Potter & Wrightington. It featured ship’s supplies including “Boston baked beans, Boston brown bread and Boston codfish balls.” A publication on the exhibition stated that “the firm of Potter & Wrightington is so old and well-established, and so widely recognized for the superiority of their goods, that they need no introduction to the people of the United States.”8

An advertising card for Potter & Wrightington Boston Baked Beans (Old South Brand) says, “For SUPERIOR excellence our brand received highest prize at Berlin, 1880, OVER all Boston competitors.”9 A late nineteenth-century ad for Van Camp’s of Indianapolis advertises “Boston Baked Pork & Beans” featuring two children each holding a can labeled baked beans. They look as though they could be Pilgrims but are actually Ludwig & Lena, patterned after the German Hansel & Gretel. Though Henry Heinz of Pittsburgh arguably popularized the German craze for baked beans beginning in 1910, Potter & Wrightington of Boston had received the highest prize in Berlin for baked beans 30 years earlier. The point is that identification with Boston was the key to selling pork & beans.

As one tracks bean migration and evolution, the confluence of multiple factors resulted in Boston’s international association with baked beans: 1) the rising power of the US Navy; 2) the leadership of Boston in canning as well as pottery firms that led in beanpot manufacturing; 3) Boston bean firms winning major international bean awards beginning at the Paris World’s Fair in 1878; and 4) the rising importance of advertising in developing national brands.

The 1890s weren’t just glorious years for the Boston Beaneaters in baseball. The years from 1890 to 1907 were the peak years of Boston being the world’s bean capital. The bean era of Boston began with the Grand Army of the Republic annual encampment being held in Boston in 1890 and ended with Boston’s Old Home Week celebration in 1907.

Any veteran with an honorable discharge from the US military was eligible for membership in the GAR. It was a potent political organization after the Civil War. Five presidents were members of the organization. During the latter part of the nineteenth century the Republican Party refused to run a candidate without the GAR’s endorsement.10

The annual encampments began in the founding year of 1866. Boston held its first in 1871, when the membership was small. When the GAR next returned to Boston, in 1890, the Civil War Union Colonel Benjamin Harrison was president, and the organization hit its membership peak of 409,489 members.11 Boston didn’t roll out a red carpet, but did present several thousand ornamental beanpots marked “Beverly Pottery” to attendees. E.B. Stillings & Co. sold metal tokens featuring a tag labeled “Dept. Mass. G.A.R” with a beanpot connected by a chain on a card stating that the souvenir was “officially endorsed.”12 There were other variations as well. It further solidified the association of Boston, baked beans, and beanpots across the nation. The items still command significant dollars today among Civil War collectors.

The bean decade of the 1890s was topped off when in 1896 an ornamental beanpot was placed on the top of the clock in the gallery of the Common Council chambers in Boston City Hall.13

As the century turned, baked beans and history continued their close association with Boston tourism. Singular or multiple beanpots were included with various Boston sites like Faneuil Hall, Paul Revere’s home, and famous churches on postcards mailed by tourists. Functional beanpots were sold, mini-beanpots were tourist collectibles, as were paperweight copper beanpots featuring Faneuil Hall and other scenes.

As the twentieth century began, the GAR was beginning a steep decline in membership as Civil War veterans died and memories became more distant. President William McKinley, assassinated in 1901, was the last of GAR member presidents. Still, the national encampment’s return to Boston in 1904 resulted in another proliferation of beanpot souvenirs. It is not insignificant that it is estimated that in 1904 approximately 94 percent of baked beans were still baked at home by housewives in beanpots.14

In 1907 the city of Boston held a celebration called Old Home Week marketed mostly to attract former residents. Almost all postcards and city materials featured at least one beanpot, or at least a small beanpot logo stamped on whatever piece of advertising material was utilized.

After 1907 Boston’s focus on baked beans had declined enough that in 1908, when the Dovey brothers purchased the Beaneaters and dressed the team in white uniforms, the media nicknamed them the Doves.

Production of canned beans had shifted from Boston as other manufacturers expanded while Boston’s declined (e.g., Van Camp’s, Heinz, Bush). Nevertheless, Boston did not totally abandon its association with beans. Boston Baked Beans, the candy covered peanuts, were invented in Pittsburgh in the early 1930s but the only connection the candy has with the baked navy beans in molasses is that peanuts and beans are both legumes.15 In 1993 the Massachusetts Legislature declared the baked navy bean the official bean of Massachusetts.16 (It is the only state to have an official bean and one of the few to even have a designated state vegetable.) And since the Beanpot college hockey tournament is an annual Boston attraction, the city has not totally lost its beans.

Red Stocking to Beaneater Base Ball

In 1871, when professional baseball first arrived in Boston, the Paris World’s Fair of 1878 was still seven years away and Boston was still getting its promotional “bean legs.” Besides, teams were commonly referred to by their city’s name, which was featured on the uniform or by the first letter (e.g., “B”). Beyond the name of the city, the teams often were referred to by the color of their stockings. In 1878, for example, the National League was particularly unimaginative. The six teams were the Cincinnati Red Stockings, Boston Red Stockings, Chicago White Stockings, Providence Grays, Milwaukee Grays, and Indianapolis Blues.

The entire “naming” problem beyond America’s largest cities (Boston, New York, Brooklyn, Philadelphia, and Chicago) was complicated by the coming and going of teams in every league. A Wolverine would briefly appear and then vanish. Some teams would be named after some variation of the most prominent player or the owners. There were even variations of that phenomenon. For example, when Cap Anson was dropped as the manager of the Chicago team, they were commonly known as the Orphans.

The first Boston baseball nickname, the Red Stockings, is the granddaddy of all baseball names since two teams still carry it: Cincinnati in the National League and Boston in the American League. Writers shortened the names to Reds and Red Sox over the years, but those names still refer back to the Red Stockings. The 1869 Cincinnati Red Stockings were the undefeated champions of baseball. When the club’s George and Harry Wright resettled in Boston in 1871, they brought the team’s name to the first professional major league, the National Association. The Boston Red Stockings dominated baseball during the National Association era. Cincinnati went back down to club-level amateur ball. The transplanted nickname carried such legendary baseball status that it stuck in Boston, at least until Cincinnati re-emerged as a baseball power.

In 1876, when the National League was founded, both Boston and Cincinnati were the Red Stockings. After the 1880 season, Cincinnati was tossed out of the National League over its failure to support NL policy banning beer and Sunday baseball. (The Cincinnati Red Stockings re-emerged in 1882 as part of the American Association.)

The NL had a huge problem. While the Providence Grays and Buffalo Bisons were established teams, the Troy Trojans and the Worcester Ruby Legs struggled. The AA had what the NL needed: New York, Brooklyn, Philadelphia, St. Louis, Cincinnati, and Pittsburgh.

The Cincinnati Red Stockings of 1882 compiled the highest winning percentage of any Cincinnati team in history, including the Big Red Machine of the 1970s. They were again the dominant Red Stockings.

The year 1882 is a bit confusing in Boston baseball nickname history: Some historians refer to the team as the Red Stockings, but a few cite Red Caps as an alternative name. A Cincinnati newspaper made a Boston Bean-eaters reference in May 1880, though it attached it to the entire city in a headline after an earthquake shook the Boston area.17

In June 1880 the Chicago Inter-Ocean noted that “two bean-eaters died at home plate,” referring to baserunners in a Cleveland-Boston game.18 In 1881 and 1882, the Cincinnati Enquirer often called the Boston baseball team the “bean-eaters.” The Detroit Free Press also began using the Bean-eater nickname to refer to the Boston team.19

What is clear is that after Cincinnati’s dominant AA championship season of 1882, Boston abandoned the Red Stockings nickname the Wrights had brought with them from Cincinnati.

Newspapers increasingly referred to them as the Beaneaters since not only had Cincinnati powerfully re-emerged with the moniker Red Stockings, but then joined the NL in 1890. The Red Stockings (e.g., Reds) name was also claimed by Boston teams in the Players’ League (1890) and the championship Boston franchise in the AA beginning in 1891 (once Cincinnati had joined the NL). While modern marketers utilize the nickname Beaneaters on baseball cards, uniforms, and other materials, the nickname does not seem to appear in primary sources other than in news coverage or informal references. Perhaps it was because the nickname was not universally adored.

In 1882, as Boston baseball transitioned to Beaneaters, a headline on the front page of the New York Tribune exclaimed: “Shooting His Companion Because He Was Called A ‘Boston Bean-Eater.’” The word was not intended as a compliment. The article began: “A shooting affray that came near to a fatal termination for one of the participants and endangered the lives of many people not engaged in it …” Two men, referred to as “confidence men” and apparently intoxicated, began arguing when the New Yorker referred to the Bostonian as a “Boston bean-eater.” The reporter noted that when the Boston man “fully comprehended the meaning of those words, he shifted his stick into his left hand while with the right hand drew a large revolver and fired with a deliberate aim at the gray-haired, bare-headed man.”20

If this were the end of this story, it would be fascinating enough, but it dragged on as a mini-press war between the two cities that was enjoyed in faraway places. A story a month later in distant Jamestown, North Dakota, quoted the Boston Journal as responding to the New York media by asserting that the shooter “may at some time have lived in Boston, but he was not – could not have been a Bostonian in the deepest and most glorious meaning of the word. Clearly a man who considers himself insulted by being called a ‘bean eater’ can have none of the commendable local pride which distinguishes the citizens of this favored metropolis.”21

Because beans were used as a cheaper, healthy substitute for meat, the term was used as both descriptive and a derogatory reference to the poor. It also could be used to convey that a person was “cheap,” substituting beans for meat when they could have afforded meat. Had the term come from a Puck satire, baseball historians might have assumed that the Beaneaters were named after penny-pinching Beaneater owner Arthur Soden.

And then there is the rather uncomfortable issue of flatulence. While it provided some occasional sarcasm from newspaper writers, the fact is that other alternative Boston names associated with the city would also have been uncomfortable at times. The early canners who made baked beans famous were also known for clam chowder and fishballs. The Boston Chowderheads or Boston Fish Balls would not have improved the situation. Had they chosen to be named after a product of co-owner William Conant’s factory, the Boston Hoopskirts would have provided much mirth.

When Beaneaters was emerging in 1883 as the universal nickname for the Boston baseball team, Boston baked beans were rising in their national fame. Boston firms won awards for their baked beans in Paris in 1878 and Berlin in 1880. The first widespread advertising of baked beans had recently begun. The baseball team nickname did not occur as an isolated event but rather simultaneously with Boston merchants’ promotional push for Boston baked beans.

How much the name change to Beaneaters inspired the Boston team to greater success in 1883 is debatable but they posted a 63-35 record and won the championship of the National League. To quote Johnny Cash’s song, “I know if papa was here right now he’d sure be pleased, And papa, if you can hear me look at them beans.”22

With all due respect to the Boston Red Sox’ transplanted Cincinnati name and the Boston Braves’ borrowed symbol from New York’s Tammany Hall, there is no more appropriate name for a Boston team than the Beaneaters. If being a beaneater was good enough for the world boxing champion, it was good enough for baseball. In 1882 a bout between American boxing champion John L. Sullivan (also known as the Boston Strong Boy) and English champion Tug Wilson was headlined “Bean-Eater and Briton.”23

It was also politically correct. The 1907 celebration of Boston Old Home Week, which featured Boston baked beans and beanpots in most promotions, was planned and staged when the Boston mayor was John F. Fitzgerald, aka Honey Fitz. He was later chairman of the Boston Royal Rooters and the grandfather of John Fitzgerald Kennedy. Honey Fitz clearly was a bean man. There can be no clearer Bostonian political stamp of approval than that.

MARK SOUDER served as the U.S. Congressman for northeastern Indiana from 1995-2010. He was a senior staff member in the U.S. House and Senate for a decade prior to being elected to Congress. Souder was one of the primary leaders of the hearings on steroid abuse in baseball. He has contributed articles to The National Pastime for the Chicago, New York, Pittsburgh, and San Diego issues. He has also contributed to four previous SABR books on the Boston Red Stockings, Puerto Rico, ballplayers and the movies, and the San Diego Padres. He also wrote the 2019 spring issue of Old Fort News on the history of professional baseball in Fort Wayne, the official publication of the Fort Wayne, Indiana Historical Society. He is retired, and lives in Fort Wayne with his wife and his books.

Notes

1 “It is for baked beans that Boston came to be known as Bean Town. The Puritan Sabbath lasted from sundown on Saturday until sundown on Sunday, and baked beans provided the Puritans with a dish that was easy to prepare. The bean pot could be kept over a slow heat in a fireplace to serve at Saturday supper and Sunday breakfast. Housewives too busy with other chores were able to turn the baking of the beans over to a local baker. The baker called each Saturday morning to pick up the family’s bean pot and take it to the community oven, usually in the cellar of a nearby tavern. The free-lance baker then returned the beans with a bit of brown bread on Saturday evening or Sunday morning.” Brett Howard, Boston: A Social History (New York: Hawthorn Books Inc., 1976), 126-127.

2 Maricel A. Presilla, “Lima Beans’ History is Ancient, Exalted,” Pittsburgh Post-Gazette, July 1, 2007. post-gazette.com/food/2007/07/11/Lima-beans-history-is-ancient-exalted/stories/200707110267; aggiehorticulture.tamu.edu/archives/parsons/publications/vegetabletravelers/beans.html.

3 Megan Gambino, “What Was on the Menu at the First Thanksgiving?,” Smithsonian.com, November 21, 2011. smithsonianmag.com/history/what-was-on-the-menu-at-the-first-thanksgiving-511554/.

4 “Out of Beans, or the Half Mast Flag,” New Orleans Times Picayune, June 20, 1839: 2.

5 oxfordreference.com/view/10.1093/oi/authority.20110803095425331.

6 “11 Things You Probably Didn’t Know About Sam Adams,” mentalfloss.com, n.d. mentalfloss.com/article/60927/11-things-you-probably-didn’t-know-about-sam-adams.

7 Roger M. Grace, “Cans of Baked Beans Produced on Mass Scale in 1878,” Metropolitan News-Enterprise (Los Angeles). The silver medal note is on a Henry Mayo & Co advertising card owned by the author.

8 John W. Ryckman, compiler and editor, International Maritime Exhibition, Boston, 1889-90, Press of Rockwell and Churchill, 325.

9 “Old South Brand Baked Beans, Potter & Wrightington; Packers of Canned Fish, Poultry, Beans, Soups &c., 197 Atlantic Ave. & 118 to 128 Commerce St., Boston, Mass.” Advertising card with drawing and additional copy on the reverse side (author’s collection), date unknown but does note, “For Superior excellence our brand received highest prize at Berlin, 1880, OVER all Boston competitors.”

10 https://ohiohistorycentral.org/w/Grand_Army_of_the_Republic. Accessed November 20, 2019.

11 http://www.treasurenet.com/forums/civil-war/73486-national-encampments-grand-army-republic.html. Accessed November 20, 2019.

12 Card: “Officially endorsed by Dept. Mass. G.A.R.; E. B. Stillings & Co., Sole Manufacturers, 55 Sudbury Street, Boston.” Attached is a small metal badge with “Dept. Mass. G.A.R.” on it with small chains holding a beanpot labeled “Beans” (author’s collection).

13 http://www.celebrateboston.com/architecture/old-city-hall.htm . Accessed November 20, 2019.

14 Jeffrey L. Cruikshank and Arthur W. Schultz, The Man Who Sold America (Boston: Harvard Business Review Press, 2010), 101.

15 Marjorie from Missouri, “Boston Baked Beans,” oldtimecandy.com, n.d. oldtimecandy.com/walk-the-candy-aisle/boston-baked-beans/.

16 https://statesymbolsusa.org/symbol-official-item/massachusetts/state-food-agriculture-symbol/baked-navy-bean . Accessed November 20, 2019.

17 “Boston Bean-eaters Shaken by an Earthquake,” Cincinnati Daily Star, May 14, 1880: 1.

18 “Boston vs. Cleveland,” Inter Ocean (Chicago), June 29, 1880: 8.

19 For example, in 1881 the Cincinnati Enquirer used Bean-eaters for the Boston NL team in May, June, July, and August. Examples in 1882 include “May 1st will settle Wise’s career as a Boston bean-eater,” section titled “Base-Ball,” Cincinnati Enquirer; April 23, 1882: 13, and “Boston Bean-Eaters Down the New Yorkers,” Cincinnati Enquirer, April 25, 1882. Other newspapers had also begun referring to the Boston team as the bean-eaters: a front-page headline in the Detroit Free Press on May 2, 1882, proclaimed that “The Bisons, Bean-eaters and Clam-eaters Beat Chicago, Worcester and Troy.” “Clam-eaters” refers to the Providence team, generally referred to as the Providence Grays. This is a great example of the fluidity of team nicknames.

20 “A Quarrel Between Confidence Men,” New York Tribune, November 13, 1882: 1.

21 Jamestown (North Dakota) Weekly Alert, December 8, 1882: 6.

22 Concluding lyrics of the song “Look at Them Beans” from the Johnny Cash album Look at Them Beans, 1975.

23 “Bean-Eater and Briton,” Black Hills Weekly Times, Deadwood, South Dakota, July 22, 1882: 1.