‘I Want to Take Your Picture!’: Reconsidering Soul of the Game and the Future of Jackie Robinson

This article was written by Raymond Doswell

This article was published in Not an Easy Tale to Tell: Jackie Robinson on the Page, Stage, and Screen (2022)

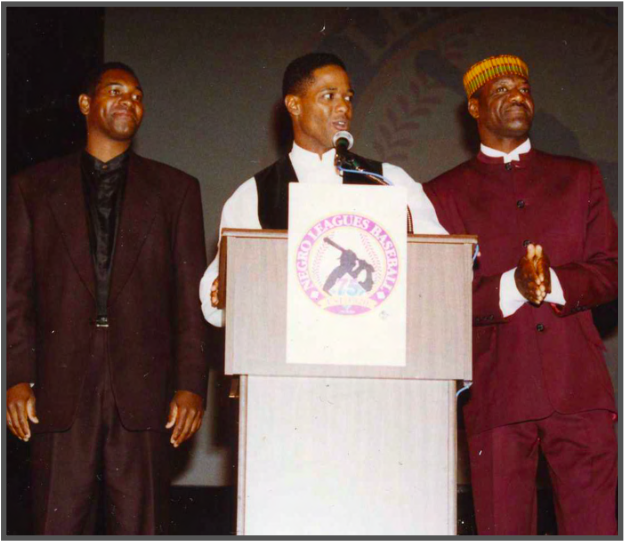

Stars of Soul of the Game, Mykelti Williamson (l.), Blair Underwood (c.), and Delroy Lindo (r.) at an event honoring the film at the Negro Leagues Baseball Museum. (Courtesy of the Negro Leagues Baseball Museum)

Soul of the Game premiered on April 20, 1996, on the Home Box Office (HBO) cable network. The docudrama interpreted the challenges and triumphs surrounding the integration of major-league baseball through the lives of three key figures from the Negro baseball leagues; LeRoy “Satchel” Paige (portrayed by Delroy Lindo), Josh Gibson (Mykelti Williamson), and Jackie Robinson (Blair Underwood).1

Soul of the Game sits within a series of dramatic film attempts to capture the experience of African-American baseball history. Since the premiere of The Jackie Robinson Story (1950), new authors and creators arrive to offer a refreshed perspective on the story. The Bingo Long Traveling All-Stars and Motor Kings (1976) for theatrical release; Don’t Look Back: The Story of LeRoy Satchel Paige (1981), Soul of the Game (1996), and Finding Buck McHenry (2000) all made for television release. These efforts were interspersed with new books and documentaries, most notably the popular Baseball: A Film by Ken Burns (1994), and many special events that highlighted a national resurgence in Negro Leagues history.

In reconsidering Soul of the Game 25+ years after its debut, it can be argued that the film ushers in a more complete interpretation of Robinson. Baseball historians, former players, and many fans feel they know this story because of Robinson’s status as a hero for baseball and civil rights. However, the persona presented in this film was revelatory to the broader public at the time. Despite some problematic licensing and storytelling, the film falls appropriately in line with other films detailing the arc of Robinson’s life, between The Court-Martial of Jackie Robinson (1990) and 42 (2013), about his spring training and first season with the Brooklyn Dodgers.

Delivering any Jackie Robinson story well and accurately weighs heavily on producers and actors, as the films become a hoped-for validation of his pioneering career and teaching tool for new generations of young fans. Moreover, for observers of Negro Leagues history, opportunities to highlight an often glossed over aspect of Robinson’s baseball experience, his one season with the Kansas City Monarchs, was enthusiastically welcomed. Robinson’s experience as a Negro Leagues infielder is dealt with in The Jackie Robinson Story, but Soul of the Game placed that experience at the center of the treatment, thus bringing new perspective to the Robinson legend.

Soul of the Game has been thoroughly critiqued and reviewed, praised for very strong portrayals by the actors, and lamented for historical departures and licenses taken by the filmmakers for the sake of drama and entertainment. The film strived to have authenticity, shooting in historic ballparks in Alabama and Indiana, as well as sets in St. Louis, Missouri. However, some highlighted stories are arranged out of sequence with the real history, such as the opening scene of baseball in the Dominican Republic (which would have been years earlier in 1937). Some events were fabricated, such as the situation of Paige and Robinson springing Gibson from a mental hospital to play in a high-stakes Negro Leagues vs. major leagues All-Star game in front of scouts at Griffith Stadium.2 Small details like incorrect uniform numbers and several other issues annoy some observers. Among the strongest charges was the fact that, historically, Gibson, Paige, and Robinson, although contemporaries and opponents, most likely did not interact as depicted in the film. Depending on perspective, these issues are at worst negligence or at best minor things to nitpick for an otherwise entertaining product.3

Creating a documentary treatment was not the filmmaker’s goal. However, the license taken, and choices made with the facts, limit the film to a character study of each historic figure. So, did the filmmakers get that right? Are we presented an accurate and compelling interpretation of the great baseball players dealing with monumental change? Examining the many aspects of those questions goes beyond the scope of this essay, but the portrayal of Jackie Robinson does earn our attention.

Exploring the development of the film and choices made by the creators reveals how Robinson’s pioneering life establishes future public perceptions of him. Underwood’s performance is more informed by material available on Robinson’s past and passions leading up to 1945. Among the many things that emerge on film is a sharper focus on Robinson as an intellectual, fiery competitor, and social crusader, and not just a passive participant in the grand schemes of Dodgers General Manager Branch Rickey. History reveals Robinson endured a long grueling season in Black baseball with great success and much media attention for his athletic abilities. We also learn that he stood in stark contrast to his peers, clashing in ideals and motivations for his life. In this film, he symbolizes the future, representing the eminent and abrupt change brought by integration in postwar America, as well as a model for the future of Black athletes.

A Season of Change

Baseball fans know the historic year 1947 as the occasion of Robinson’s first major-league season, but they know fewer details of Robinson’s ascendance from the Negro Leagues. The setting for Soul of the Game is the pivotal year 1945. The real history shows a 26-year-old Robinson looking to pursue opportunities to earn money for his family. He experienced a tumultuous final year in the U.S. Army, and now aspired to marry his fiancée Rachel Isum. Robinson is a known sports celebrity, having made headlines in collegiate football, basketball, and track. However, he arrives at the February spring training in Texas for the Kansas City Monarchs rusty on baseball skills and out of conditioning.

The Monarchs, like many teams in baseball, were depleted of talent due to World War II, but whipped themselves into shape for a May 6 regular season opening. There was even an early spring tryout invitation of Black players for major league baseball’s Boston Red Sox, that included Robinson. It was arranged through pressure on the team from the Black press, but it yielded no job offers for the participants.

The Monarchs were on the road constantly, and Robinson earned high praise and media attention for his efforts. Satchel Paige formally joined their travels in late May and made eight known league appearances with the Monarchs between pitching-for-hire/gateattraction opportunities around the country. Team tours included southern and east coast swings, facing teams like the Homestead Grays and slugger Josh Gibson. Robinson generally batted third in the lineup and was rewarded with selection to the East/West All-Star Classic in Chicago. The most complete data shows Robinson appearing in 34 out of 75 league games, with a .375 batting average, four HRs, and 27 RBIs. Paige, at age 38, had three wins against three losses, one complete game, 3.55 ERA, 41 strikeouts, and surrendered 10 walks over 38 innings.4

The grinding season was winding down with no postseason for the Monarchs. They finished second in the Negro American League to the Cleveland Buckeyes, who swept Gibson’s Grays in the Negro World Series. Gibson maintained his solid seasonal play, hitting for a .372 average over 43 recorded regular-season league games, but could muster only two hits and two walks in the championship series.5

Robinson had come to a troublesome crossroads of frustration with segregated baseball and a need to make a living. He was summoned to speak with the Brooklyn GM Rickey and offered a minor-league opportunity with the team. The Dodgers had embarked on a clandestine effort to recruit Black players under the ruse of developing a separate Black major league. Robinson’s acceptance marked the break that helped his immediate situation and set him on an unimaginable historic path.

Baseball in Black and White

In fall 1995, HBO announced Lindo, Williamson, and Underwood would begin October filming of Baseball In Black and White.6 At about the same time, there were other potential treatments on Black baseball history in the Hollywood pipeline, including separate announced projects in early 1995 by directors John Singleton and Spike Lee. With the hot progressive directors getting all the media attention, there must have been some pressure on HBO to bring their project forward. Ultimately, the logjam of films was avoided as HBO was first to get a script into production. The other projects have yet to be produced.7

All these film endeavors rode a wave of culturally broad, increased interest in Black baseball history. Historian Dan Nathan described it as a “steady historical revival” since the 1970s, featuring new research, new exhibitions, player appearances, baseball apparel, and commercial opportunities. “Collectively, these and other cultural texts suggest that more white people may be aware of, knowledgeable about, and interested in the Negro leagues today than when the leagues actually existed.”8

Soul of the Game was directed by Kevin Rodney Sullivan based on a script by David Himmelstein. After reviewing several potential treatments, Sullivan was drawn to Himmelstein’s creative choices. “It found the right time frame for the story because [1945] was the year Jackie was a rookie [for the Kansas City Monarchs]. It brought those three men into the same arena at the most crucial moment and really got us into the race to be first.”9

“It’s an extraordinary story of extraordinary characters at an extraordinary time. The country was going through a huge flux,” Himmelstein told the Washington Post. In taking license with the factual accuracies of the story, he added that the goal “was to be true to the spirit of the major players. Every time you try to compress a man’s life, let alone three lives, into two hours, there’s going to be distortion.”10 Himmelstein reflected on his choices 25 years later:

Sometimes you have to bend the facts in service of the human drama. When I was writing Soul of the Game I portrayed Josh Gibson, Satchel Paige and Jackie Robinson as being a lot friendlier than they actually were to each other when they were playing in the Negro Leagues right after World War II. People who were experts immediately pointed that out. But your primary duty is to the story, using it as a springboard to illuminate greater truths. And that same dynamic and push-pull is there.11

At some point, the name of the film was changed from Baseball In Black & White, to Soul of the Game. It is unclear when or why it changed, but the new title became permanent by early 1996.

Blair and Uncle Eli

Excited to play a leading role in the film was actor Blair Underwood. By 1995, the 30-year-old Underwood had a decade of noteworthy television acting credits. The former athlete seemed well suited for the role, both in interest and pedigree. “Football was primarily my game,” he told the Washington Post. “My father was a four-letter man, not unlike Jackie Robinson. But my great uncle, Eli Underwood, played with the Detroit Stars and barnstormed with the Pittsburgh Crawfords and the Homestead Grays. I’ve always heard about the Negro Leagues from him.”12

Underwood family roots are traced to the 1850s in Perry County, Alabama. Blair’s grandfather was Ernest Underwood (born around 1902). Ernest’s brother Eli (born around 1906) and their three other siblings were raised by father Robert and mother Isabelle, who were farm laborers. Within a decade of Eli’s birth, the family moved north, and Robert worked in the steel mills of Steubenville, Ohio. Eli would later work in the mill, but soon picked up baseball opportunities for Black barnstorming and league teams.

In the 1930s, Eli Underwood pitched and played outfield with the Buffalo Giants based in Steubenville and the Cuban Giants of Grand Rapids, Michigan, which morphed into the Cincinnati Cuban Giants in 1935. Later, he joined the reformed Detroit Stars, part of a new Negro American League, in 1937. One Underwood family legend recounts that Eli, known for having large feet, had Satchel Paige stealing his shoes in a prank. “But Satch gave them back the next day. My great uncle has big feet, but his shoes weren’t big enough for Satch,” Blair recalled. After baseball, Eli served in the United States Navy.13

Eli’s older brother Ernest also worked in the Ohio steel mill but later became a police officer. With wife Beatrice they had four sons, including Frank, who became an Army Colonel. Military life took Frank Underwood and family to many national and international locations. Their son Blair was born in 1964 at Tacoma, Washington.

Psychological Makeup

Blair Underwood enthusiastically embraced the challenge of playing Robinson but knew he had work ahead of him to get it right. “I was excited when this came along. There haven’t been many stories like it. There was The Bingo Long Traveling All-Stars & Motor Kings, but that was more fictitious,” he noted.14 From his family, Underwood had deep perspective on the Black working class, Black migration, baseball history, and military life; all important components to understanding Jackie Robinson. He still wanted to learn more to play the role effectively:

I knew about Robinson’s natural talents and the taunts and insults he faced from racist fans, but I didn’t know anything about his psychological makeup. . . I didn’t know that this man had a hell of a temper and had to learn how to control it. In my mind, he was someone who pacifically turned the other cheek. Nothing could be further from the truth.15

Underwood gleaned even more insights from a noteworthy eyewitness to history, veteran actress Ruby Dee. Dee was Black cinematic royalty. With husband Ossie Davis, the actress had blazed a historic trail of theater, television, and film appearances. She enjoyed one of the most synergistic career arcs in history. Dee starred as young “Rachel Robinson,” Jackie Robinson’s wife, in the 1950 film The Jackie Robinson Story. Then 40 years later, played Robinson’s mother Mallie opposite Andre Braugher as “Lt. Jackie Robinson” in the 1990 television film The Court-Martial of Jackie Robinson. In addition, Dee and Davis were great friends with the Robinsons for many years, supporting numerous civil rights initiatives together. Underwood recalled:

She found it hard to believe the image that was presented was the man she worked with. He was decent and hardworking, but also a man with a temper that he had to learn to control. I did not know that. I remember hearing he had to deal with a lot of mess from people, but the fact is he did not always want to turn the other cheek. 16

Jackie Robinson as an angry Black man is a revelatory nuance that Underwood brings to audiences. Himmelstein’s script highlighted this perspective, adding to the drama of the story in many scenes. Many other reflections on Robinson were available to the film creators to inform this perspective.

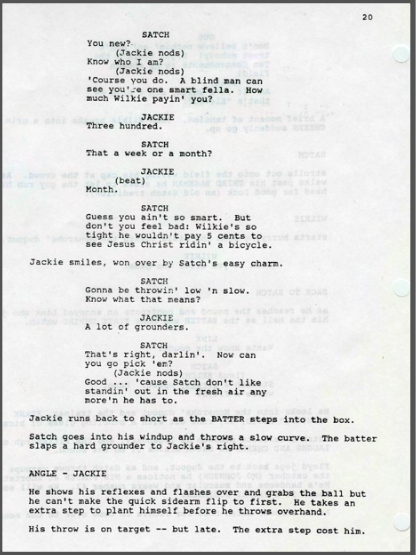

A page from the script of Soul of the Game. (Courtesy of the Negro Leagues Baseball Museum)

“And he would fight!”

Among available material in the mid-1990s exploring Robinson’s life was his autobiography I Never Had It Made. In collaboration with Alfred Duckett, Robinson completed the work shortly before he passed away in the early 1970s. In it, Robinson explains his disdain for life in the Negro Leagues and the many pressures weighing on him before his meeting with Branch Rickey. As he explains, the prospect of making $400 a month when he was recruited to the Monarchs was a “financial bonanza” after being discharged from the Army. However, it turned out to be “a pretty miserable way to make a buck.”17

When I look back on what I had to go through in black baseball, I can only marvel at the many black players who stuck it out for years in the Jim Crow leagues because they had nowhere else to go. . . These teams were poorly financed, and their management and promotions left much to be desired. Travel schedules were unbelievably hectic. . . This fatiguing travel wouldn’t have been so bad if we could have had decent meals.18

It was an extremely stressful time for Robinson. He felt “unhappy and trapped” as he questioned his future.19

The book Baseball’s Great Experiment: Jackie Robinson and His Legacy by historian Jules Tygiel appeared in 1983. Tygiel’s seminal work captured important aspects of the Robinson story and beyond. Attention was paid to Robinson’s disdain for prejudice he faced in his youth, the military, and during his time in the Negro Leagues. Tygiel interviewed many of Robinson’s contemporaries, who years later also confirmed Robinson’s temper, competitiveness, and social isolation:

The Robinson personality had been created by these experiences. His fierce competitive passions combined with the scars imbedded by America’s racism to produce a proud yet tempestuous individual. . . His driving desire for excellence and his keen sense of injustice created an explosive urge.20

According to Tygiel, this reputation preceded Robinson, but was noted as an unfair critique initially by Branch Rickey because Robinson was known to stand up to White authority. However, Tygiel surmised that Robinson “was the most aggressive of men, White or Black,” and that his “coiled tension, increased by [his] constant and justifiable suspicion of racism, led to eruptions of rage and defiance.”21

Moreover, Robinson was a devout Methodist, a non-drinker, and non-smoker. Biographer Arnold Rampersad described it as a “priggish” attitude towards morals and mores.22 Much of his attitude clashed ideologically with teammates and stirred-up commotions. Tygiel and Rampersad (writing in 1997) both record accounts from former Negro Leagues players as examples.

Blair Underwood picked up on his unique nature in his studies of Robinson:

He was kind of an outsider in the Negro Leagues. . . When Branch Rickey approached him about moving to the Dodgers, he had to keep it a secret awhile. But it wasn’t that difficult to keep a secret among the players because he was never totally in that inner circle. So that just speaks to his alienation.23

The Court-Martial of Jackie Robinson appeared on TNT Television in October 1990. As noted earlier, Ruby Dee and Andre Braugher star in a story that was little known to many, including Braugher. For authenticity, Braugher spoke to his own family members about military life, leaned on reading I Never Had It Made, and got first-person advice from Rachel Robinson, who advised the project and visited the set during filming.

A final resource available for Soul filmmakers to review was Baseball: A Film by Ken Burns which debuted on Public Broadcasting Service (PBS) in fall 1994. “Inning 6, The National Pastime” dealt almost exclusively with Robinson’s journey from the Negro Leagues to the Brooklyn Dodgers. In the film, viewers meet Sammy Haynes, a catcher, teammate, and roommate of Robinson with the Monarchs in 1945. Haynes was an eight-year veteran of the Negro Leagues and in his third and final season with the Monarchs when Robinson joined the team. Haynes recalled stories of a rookie who humbly and willfully sat in the stairwell of the crowded team bus on a road trip. He also acknowledged concern for Robinson’s ability to handle the abuse to come after deciding to join the Dodgers:

The one thing we (players) weren’t sure of was if Jackie could hold his temper. . . He knew how to fight, and he would fight! If Jack could hold down that temper, he could do it. He knew he had the whole black race, so to speak, on his shoulders. So, he just said ‘I can take it, I can handle it. I will take it for the rest of the country and the guys,’ and that’s why he took all that mess.24

“I’m playing my position, Mr. Paige!”

In Soul of the Game, Robinson’s isolation, hostility, and tenacity are presented right away in the introduction of the character. In one of the film’s signature moments, Underwood’s first words of dialogue have Robinson in defiance of Satchel Paige. During a game versus the Homestead Grays, Paige walks in off the street, late for the game start, to relieve Hilton Smith with runners on base. He immediately throws a double play ball to ease the threat. Then, Paige famously “calls in the outfielders” to leave the field when Josh Gibson comes to bat. Historically, this gag bit had become a signature fan favorite antic employed by Paige. The crowd erupts in approval, but shortstop Robinson is not amused. As Gibson stands in the batter’s box, Paige, annoyed, turns to Robinson, who has not left the field:

Paige: What are you doing?

Robinson: I’m playing my position, Mr. Paige!

Paige: (chuckles) Boy, you don’t even know yo’ position. Let me help ya out. Yo’ position on this team, is right over there (pointing to the Monarchs bench).

Robinson: (angrily) You’re not pitching, you’re putting on a bullshit show. . .

Paige: Wait a sec, hold up there, junior! This my game. This is my game and my show! And you best learn how to act in my show!

Team manager Frank Duncan (Brent Jennings) runs out to retrieve Robinson. With the crowd now jeering him for defying Paige, he storms off the field and confronts Monarchs team owner J.L. Wilkinson (R. Lee Ermey) in the dugout:

Robinson: I signed onto this organization to play baseball. This is not baseball! You got clowns out there doing some kind of song and dance; how do you expect me to do my job. . .

Wilkinson: (interrupts) Hey, don’t you tell me what’s baseball! That clown out there is paying your wages. (dismissively) Do you think all these people came here to today to watch Jackie Robinson?

Gibson: (mumbles to the catcher) Lawd, they gettin’ younger and stupider.

It is interesting to note that, in an early draft of the script Baseball in Black and White, this scene features the initial exchange of Paige and Robinson much friendlier, before it descends into the chaos to follow. By condensing the scene, an interesting editorial choice is made to have Underwood’s Robinson make his first impression towards Paige more defiant rather than reverential. The earlier version, which was not used, reveals Paige, still ever the showman, initiating veteran advice for Robinson to ease the rookie’s tension:

Paige: You new?

(Robinson nods.)

Paige: Know who I am?

(Robinson nods.)

Paige: ‘Course you do. A blind man can see you’re one smart fella. How much Wilkie payin’ you?

Robinson: Three hundred

Paige: That a week or a month?

Robinson: Month.

Paige: Guess you ain’t so smart. . .But don’t you feel bad; Wilkie’s so tight he wouldn’t pay 5 cents to see Jesus Christ ridin’ a bicycle!

(Jackie smiles, won over by Satch’s easy charm.)

Paige: Gonna be throwin’ low and slow. Know what that means?

Robinson: A lot of grounders.

Paige: That’s right darlin’. Now can you go pick ‘em?

(Jackie nods)

Paige: Good. . .’cause Satch don’t like standing out in the fresh air any more ‘n he have to.25

After a couple of fielding miscues and close defensive plays by Robinson, Paige tries to calm the frazzled Robinson:

SATCH Rubs the ball and looks over at Jackie as the fans JEER.

Paige: Don’t worry ‘bout that. Just take your phone off the hook an’ do it!26

Little has been chronicled about the relationship of Paige and Robinson in real time. Publicly, they showed great admiration for one another, especially when the announcement came near the end of 1945 that Robinson was chosen by the Dodgers for a contract. However, Paige biographer Larry Tye suggested more of a schism existed privately. Paige certainly expressed great disappointment to family and close friends that he was passed over for Robinson. He seemed to hold no personal grudges, but was confused that, with all he had done in baseball, a rookie on his primary team would be the choice. Conversely, Tye describes fellow baseball barrier-breaking player Larry Doby and Robinson as “dourer” men than Paige. He quotes Doby saying Robinson “detested” Paige:

Satch was competition for Jack. Satch was funny, he was an outstanding athlete, and he was black. He had three things going. Jack and I wouldn’t tell jokes. We weren’t humorists. We tried to show that we were intelligent, and that’s not what most white people expected from blacks. Satch gave whites what they wanted from blacks—joy.27

The character set to personify and respond to internal team tensions brought by Robinson is Jesse Williams (Joseph Latimore). In the film, Williams is initially supplanted at shortstop upon Robinson’s arrival, but Paige later asks manager Duncan to move him to second base because he showed a lack of arm strength. That news came after fisticuffs between Robinson and Williams. Latimore plays Williams as a bitter thorn on Robinson’s psyche, picking at his seemingly fragile temper like a scab. He is resentful of Robinson’s perceived pretensions, and it boils over when he reads a newspaper story praising Robinson. This scene in the Monarchs locker room has Williams taunting Robinson loudly in front of the team:

Williams: I think Wilkie finally went out and got himself a good ol’ white boy! Oh yeah, he looks black enough y’all! Show don’t sound like it. Maybe like some fancy house n___. . .

The insult was a dare and got the expected effect of lighting Robinson’s fuse in retaliation. Williams taunting seems to represent some comeuppance for Robinson’s perceived snobbishness while adding a bit of rookie hazing.

The real-life Jesse Williams, by most accounts, may not have been such an instigator. Jesse “Bill” Williams from Texas was a respected premier infielder in the Negro Leagues. He joined the Monarchs in 1939, was a two-time Negro Leagues All-Star, and a key member of the 1942 championship team. Although he had a stellar 1944 season at shortstop, he was switched to second base to help make room for Robinson on the team. The move was seen as positive, but 1945 was Williams’ last full year in the Negro Leagues. Robinson and other Black players advanced to the major leagues while Williams toiled in Mexico and on barnstorming teams for another decade. If he shared any resentment of Robinson, it does not appear reflected in any interviews or published material.28

A New Generation

Pivotal points of the film turn on discussions of Robinson’s time in the military. The news article that stirred envy in the Williams character was an interview conducted the previous day by the local news reporter and photographer (Bruce Beatty) after Robinson’s defiant response to Paige on the field. After the embarrassing incident, Robinson came to bat, legged out a double with blazing speed, then scored on a botched throw to third after he stole the base. In the locker room after the game, the reporter is initially regaled by Paige with folksy witticisms before turning questions to Robinson:

Reporter: Hey um, Robinson? Satch says your problem is you got a bad temper.

(Robinson glares at the reporter while getting dressed, then tries to ignore him.)

Reporter: Hey, are you the Jackie Robinson that played half-back at UCLA?

(Robinson nobs, sheepishly, yes.)

Reporter: Damn, I knew it, just by the way you were running those bases! I heard you just got out of the army.

Robinson: That’s right.

Reporter: So, what did you do?

Robinson: (standing) Platoon leader, 761st Tank Battalion, Fort Hood.

Reporter: You a Sergeant?

Robinson: Lieutenant.

Reporter: An officer? Man, in that kind of position, what you were doing must seem a lot different from this?

Robinson: Well, I don’t know, but there are some areas where the skills are similar.

Reporter: Like what?

Robinson: (with quiet confidence, but loud enough for everyone to hear) Like the discipline of managing your time. Setting goals. Taking personal responsibility for seeing them through. Ya’ know, things like that.

Reporter: (impressed) I want to take your picture!

It’s an important scene, meant to showcase Robinson’s confidence and intelligence. Moreover, it is meant to signal future change. The reporter realizes and appreciates he is witnessing someone of impact, unlike any athlete he has known. This scene survives the many script edits the film would undertake, and Himmelstein’s notes in the early draft of Baseball In Black and White highlight the significance he hoped for with the exchange:

CLOSEUP- SATCH: For the first time, he begins to realize that if the ‘New Age’ ever does come, he may be left behind. It is painfully obvious that Jackie is from a new generation, and he, while still vibrant and successful, is inarguably from the old. ‘POP’ – his face is illuminated in the reflected light of the big flash as the reporter snaps Jackie’s picture.29

In the film, Robinson’s military record and courage do impress his teammates and is used to grant him a measure of bona fides or credibility. J.L. Wilkinson relates the story of Robinson’s military court-martial to imply why Williams and others should back off on hazing Robinson. Before heading out of town on a road trip:

Monarch player: Hey, did Robinson get traded?

Wilkinson: He and Satch got loaned to Harrisburg. They’ll catch up to us in New York.

Williams: Good! Don’t want him on our bus no-ways.

(Wilkinson chuckles)

Williams: What’s so funny?

Wilkinson: Well, Robinson and buses.

Williams: Yeah, what about it?

Wilkinson: Well, when he was in the service, some driver told him to get to the back of the bus. He set the guy straight and got himself court-martialed.

He beat it, too.

IN TEXAS.

Let’s go guys. (Pointing towards the bus).

Monarch players who were listening nod, impressed by the story.

Williams: (a bit awed by the story reacts quietly) Good for him.

Determined Yet Confused

Most film reviews and critiques of Soul of the Game exalt Delroy Lindo’s performance as Satchel Paige the driving force of the production, and rightfully so. All the actors received high marks, but comments on Underwood’s Robinson were more muted. However, in his review of the film, Phil Gallo of Variety Magazine adequately summarizes the film and Robinson’s portrayal:

The riveting depth of the telefilm’s p.o.v. is embellished by the stellar acting, which dissipates any concern for the blurring of fact and fiction. . .. Underwood plays Robinson as determined yet confused, cautious in his acceptance of the role Rickey assigns him. Robinson’s collected nature is emphasized over his athleticism, contrasting with the veterans’ determination to cross baseball’s color line.30

Director Kevin Rodney Sullivan hoped that Soul of the Game could show viewers that the Negro Leagues, “was a great thing all to itself,” and that it “celebrates what was there and not just what they (players and fans) didn’t have.”31 That sentiment comes through early in the film, but the core of the story was to capture the moment when feelings change towards aspirations of something new – the major leagues. Jackie Robinson is the agent of change.

Despite the objections of some observers and criticism of its overall approach in telling the history, Soul of the Game did succeed in bringing audiences closer to the historical Jackie Robinson in full. His complexity, passion and competitive fire become clearer through the years after 1996 and bring us nearer to knowing who this consequential man truly was.

RAYMOND DOSWELL, Ed.D. is Vice-President of Curatorial Services for the Negro Leagues Baseball Museum in Kansas City, Missouri. He manages exhibitions, archives, and educational programs. He holds a B.A. (1991) from Monmouth College (IL) with a degree in History and training in education. He taught high school briefly in the St. Louis area before attending graduate school at the University of California-Riverside. He earned an M.A. (1995) in History with emphasis on Historic Resources management. Doswell joined the staff of the Negro Leagues Baseball Museum in Kansas City, MO in 1995 as its first curator. The museum has grown into an important national attraction, welcoming close to 60,000 visitors annually. He earned a doctorate in Educational Leadership (2008) from Kansas State University through work in partnership with the museum to develop educational web sites and programs.

Notes

1 In December 2020, Major League Baseball announced that seven of the Negro Leagues would be defined as major leagues. This was not the reality experienced by Jackie Robinson and others. Acknowledging that reality, this article will reflect the distinction prior to the recent (and welcome) recognition.

2 Retrosheet.org notes several Negro Leagues vs major-league exhibition games in October of 1945, including a five-game series played on consecutive Sundays featuring players led by Biz Mackey for the Negro Leaguers and Charlie Dressen for the “major leaguers.” Although the games featured future Black major-league players, such as Monte Irvin and Don Newcombe, neither Paige, Gibson, nor Robinson participated. https://www.retrosheet.org/NegroLeagues/1945IR.html. See also William Brashler, Josh Gibson: A Life in the Negro Leagues (Chicago, Ivan R. Dee Publishing, 1978), 133. Brashler references that Gibson would be hospitalized and released on weekends to play, accompanied by hospital attendants, which is like the scenario depicted in the film.

3 A complete and thorough autopsy of Soul of the Game can be found at the “Underdog Podcast,” https://underdogpodcasts.com/soul-of-thegame; see also contemporary reviews and analysis, David Bianculli, “Soul of the Game Hits a Triple,” New York Daily News, April 19, 1996; Hal Boedeker, “The Acting is a Hit, but HBO’s ‘Soul of the Game’ Delivers More Myths than Facts About Three Legends of the Negro Leagues,” Orlando Sentinel, April 20, 1996; Paul Petrovic, “‘Give ‘Em the Razzle Dazzle’: The Negro Leagues in The Bingo Long Traveling All-Stars and Motor Kings and Soul of the Game,” Black Ball Journal, Volume 3, no. 1, Spring 2010, 61-75; Lisa Doris Alexander, “‘But They Don’t Want to Play with The White Players, Right?’: Depictions of Segregation and Negro League Baseball in Contemporary Popular Film,” Black Ball Journal, Volume 5, no. 2, Fall 2012, 19-34.

4 Jesse Howe, “1945: Jackie Robinson’s Year with the Kanas City Monarchs,” Flatland Newsletter web site, https://www.flatlandkc.org/people-places/1945-jackie-robinsons-year-kc-monarchs/; Aaron Stilley, “Jackie with the Monarchs: Reliving the 1945 Kansas City Monarchs Season,” blog http://jwtm1945.blogspot.com/; www.Seamheads.com Negro Leagues Database.

5 www.Seamheads.com Negro Leagues Database.

6 “HBO’s Coming Attractions,” Los Angeles Times, September 25, 1995.

7 Although the film was never produced, in March 2020, Spike Lee released a completed version of his Jackie Robinson script, free for the public to review on his social media platforms. A live virtual table reading was conducted by the Los Angeles based arts group The Talent Connect on April 15, 2020.

8 Daniel A. Nathan, “Bearing Witness to Black Baseball: Buck O’Neil, the Negro Leagues, and the Politics of the Past,” Journal of American Studies, volume 35, no. 3, 2001, 453-469.

9 Susan King, “The Hard Run to First,” Los Angeles Times Magazine, April 14, 1996: 5.

10 Michael E. Hill, “HBO’S Film Touches Heart of the Matter,” Washington Post, April 14, 1996.

11 Drew Himmelstein, “A Talk with My Dad, screenwriter of ‘My Name Is Sara,’ his first Jewish film,” Jewish News of Northern California, February 4, 2021.

12 Hill, Washington Post

13 Hill, Washington Post; family research from www.Ancestry.com U.S. Census records; Eli Underwood baseball research courtesy of historian Gary Ashwill and www.Seamheads.com Negro Leagues Database.

14 Hill, Washington Post.

15 Eirik Knutzen, “Soul of the Game Recalls Pivotal Point in Baseball History,” Copley News Service and the News-Pilot, San Pedro, California, April 16, 1996.

16 King, Los Angeles Times Magazine.

17 Jackie Robinson, I Never Had It Made: The Autobiography of Jackie Robinson (New Jersey, The Ecco Press, 1995), 23.

18 Robinson, 22-23.

19 Robinson, 23

20 Jules Tygiel, Baseball’s Great Experiment: Jackie Robinson and His Legacy, Expanded Edition (New York, Oxford University Press, 1997), 62.

21 Tygiel, 63.

22 Arnold Rampersad, Jackie Robinson: A Biography (New York, Alfred A. Knopf, 1997), 118.

23 King, Los Angeles Times.

24 Baseball: A Film by Ken Burns, “Inning 6: The National Pastime, 1940-1950,” Florentine Films, 1994.

25 David Himmelstein, “Baseball In Black and White, First Draft Re visions, June 1995,” HBO Films, 20. Script is from the collection of the Negro Leagues Baseball Museum

26 Himmelstein, 21.

27 Larry Tye, Satchel: The Life and Times of an American Legend (New York, Random House, 2009), 200.

28 Tim Hagerty, “Jesse Williams,” SABR BioProject, https://sabr.org/bioproj/person/jesse-williams/.

29 Himmelstein, 28.

30 Phil Gallo, “Soul of the Game,” Variety Magazine, April 18, 1996.

31 King, Los Angeles Times Magazine.