Identifying Undated Ticket Stubs: An Attempt to Recapture Baseball History

This article was written by Dr. James Reese

This article was published in Spring 2014 Baseball Research Journal

Some professional baseball teams did not include dates on regular season tickets before 1974. Therefore, many stubs exist as a tangible part of sports history, but remain unidentified and have lost their historical significance.

This study attempts to identify pre-1974 regular season grandstand and bleacher tickets issued by the New York Yankees. Numerous unique details exist on ticket stubs to assist researchers in trying to identify the date each ticket was used. These unique details include, but are not limited to, printer logos and names, team logos, ticket back language, ticket prices, game numbers, the names of general managers or team presidents, and various numbers and letters printed on tickets. These individual details may be used to narrow the date range of a particular ticket. However, in most instances, multiple data must be used to identify the exact date of a ticket stub. Even so, in some cases, identifying an exact date is impossible. Historical ticket samples will be presented as well as techniques to limit the range of dates each ticket sample was issued.

These techniques provide historical context to previously unidentified ticket stubs. This assists collectors and authenticators in the identification of undated stubs. It also serves as a lesson to sport administrators in regard to the need to deliver value back to fans from a customer service perspective. To many fans, tickets do more than grant access to stadiums; they are a permanent link to sports history.

Prior to approximately 2003, when ticket scanners became prominent at sports facilities, ushers would tear tickets into two pieces returning a piece to the user.1 The stub typically included the respective seat location to serve as a receipt for the stub holder.2 The stub also allowed fans to return to the facility in the event a game was cancelled due to rain. In fact, “Rain Check” is printed on many old ticket stubs. (See Figure 1.)

As the field of sports memorabilia continues to grow, collecting ticket stubs, once an overlooked part of the industry, is becoming a more popular segment of the memorabilia market.3,4

As actual pieces of sports history, ticket stubs have a real connection to a sporting event. Unlike sports trading cards, ticket stubs were not printed to meet consumer demand. Tickets were limited to the seating capacity of the home team’s facility.5

Ticket distribution was further restricted by the actual attendance at the event. In addition, at the time, ticket stubs were not generally viewed as collector’s items. Few survived in pristine condition since they were folded and placed in pockets, wallets, game programs, etc. Some were also damaged by rain, residue from concessions, rubber bands, paper clips and staples. Many ticket stubs were discarded after the respective event making surviving ticket stubs even more rare.6,7,8

Researching ticket stub collecting is difficult due to a lack of information. According to sport memorabilia authenticator and author Joe Orlando, “The problem has been and continues to be a real lack of available information about them. How scarce are they? What are they worth? What collecting themes are popular? The questions are numerous, but there’s no doubt that tickets are gaining in popularity.”9,10

As ticket stub collecting continues to grow, the most desired ticket stubs will likely be those with the most historical significance. When reviewing the top 15 most sought after ticket stubs in the sports memorabilia field in all sports, four of the tickets involve the New York Yankees.11

As collecting ticket stubs continues to gain popularity, the ability to identify previously unknown undated ticket stubs should help to make historical ticket stubs more popular to collectors.

Historical Significance

The original Yankee Stadium opened on April 18, 1923, hosting more than 74,000 fans. It is estimated that an additional 15,000–25,000 fans who wanted to purchase tickets were turned away that day. Due to demand for tickets the gates closed a half hour before the start of the game. Grandstand tickets were priced at $1.10.12,13,14,15

Some of the greatest games played at Yankee Stadium took place between 1923 and 1964. For example, some of the greatest home run hitters in Yankees history played during this period. Mickey Mantle hit the most home runs at Yankee Stadium, with 266, followed by Babe Ruth with 259, and Lou Gehrig with 251.16 Undated tickets at Yankee Stadium appear to be limited to bleacher and grandstand seats. The latest confirmed undated bleacher and grandstand tickets from Yankee Stadium are from 1973, the year before Yankee Stadium’s second renovation.

Relevance to Sports Management

Research on fan identification, referred to as the strength of a fan’s emotional attachment to a sports team, indicates fans with high levels of team identification attend more games, have a long-term commitment to their team, and spend significantly more money on team merchandise.17 This serves as a lesson to sport administrators in regard to the need to deliver “added value” back to fans. To many fans, tickets do more than grant access to stadia; they are a permanent link to sports history. Tickets from sporting events are saved and passed down from one generation to another in many cases. Recognizing that fans collect team merchandise and memorabilia creates an opportunity to use items such as tickets to better market the team. Since team administrators never know when a momentous event may occur, including the date of the game on the ticket is a simple way to capture historic occasions. Tickets may also be used as a marketing device in other ways. Issuing differently designed tickets to season ticket holders, or issuing tickets that include photos of current or past players, significant moments in team history, or even artwork created by fans are a few additional examples.

Narrowing Years and Identifying Games

A number of items printed on undated Yankees grandstand and bleacher ticket stubs may help identify the year each was issued. The technique used to identify undated ticket stubs is similar to the technique used by baseball researcher George Michael to identify mystery photos.18 The technique includes reviewing the items for clues that may provide a range of dates that may allow the items to be conclusively identified. The following is a list of details printed on undated ticket stubs that may assist in their identification.

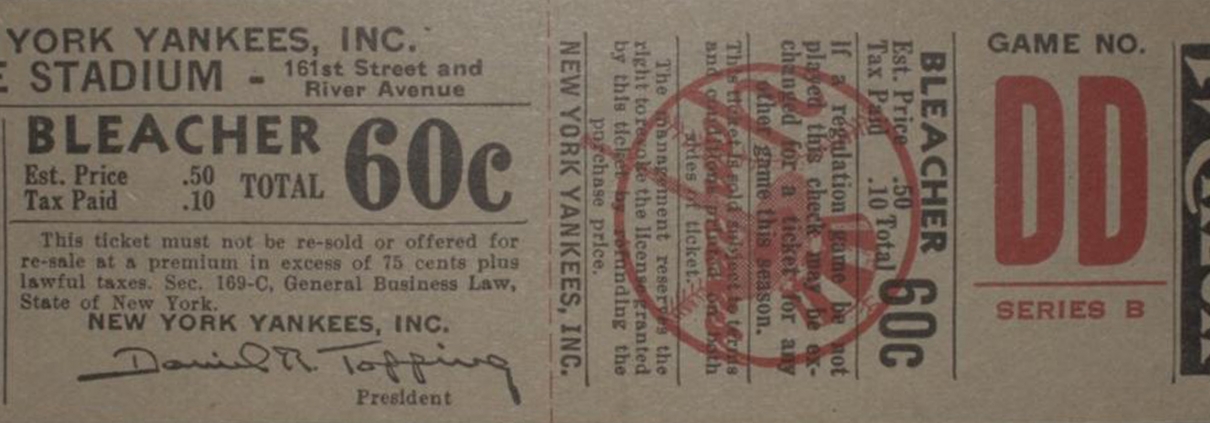

Name of Team President or General Manager. Vintage Yankees ticket stubs contain the name of the owner, team president, or general manager (Figure 1). Since years of service are well documented for owners and team executives, this datum may be used to identify a range of years when ticket stubs were printed. For example, Yankees executive Larry MacPhail was the team president and general manager 1945–47. He was listed as team president on all regular season grandstand and bleacher tickets. Since MacPhail’s name only appears on ticket stubs for three seasons, this can be used in combination with other data to narrow the issue dates of undated stubs. Table 1 summarizes the combination of New York Yankees owners, team presidents, and general managers whose names have appeared on grandstand and bleacher ticket stubs 1903–73.19,20

Rain Check Logos. No less than four different styles of rain check logos were used on Yankees grandstand and bleacher seat ticket stubs from 1923 to 1964. Figure 2 illustrates three of the four designs with similar rain check logos. The fourth rain check logo was not included in the illustration since it is unique and appears to have only been issued for promotional events. Since the actual rain check script on the samples illustrated in Figure 2 is identical, the differences are subtle, such as a thin line above or below the rain check script. One sample has lines above and below, another has no lines at all, while a third includes only a line below. However, each design, subtle or significant, may ultimately be used to identify the year, or range of years, the ticket stubs were issued.

Price and Amount of Sales Tax Printed on Tickets. The face value of a ticket, as well as the amount of tax printed on the ticket, may help narrow the age of the ticket stub. For example, existing Yankees ticket stubs indicate that the most common ticket prices post 1923 through the early 1940s was $1.00 for grandstand tickets and .50 for bleacher seats. The price of .50 for bleacher seats is documented through 1951. In addition, a tax of 10% was charged on grandstand tickets, bringing the total cost to $1.10, while bleacher seats included a tax of .10 (20 percent) bringing the cost to a total of .60. Though it is not known when in the 1940s the grandstand ticket price was raised to $1.04, a documented 1947 ticket stub includes a ticket price of $1.04 plus a tax of .21. This indicates that at some point in the 1940s the tax on grandstand tickets was increased from 10 to 20 percent. Looking at vintage ticket stubs from other professional baseball teams provides some additional information in regard to the tax included on ticket stubs. For example, an undated ticket stub from a game hosted by the Philadelphia Phillies reveals that one of the taxes paid by fans was a federal tax while another was a city amusement tax. (See Figure 3)

Another interesting tax that appears on ticket stubs is a war tax. This was a tax imposed by the U.S. federal government to offset the cost of World War I. The actual wording “War Tax” appears on 1921 World Series ticket stubs between the New York Yankees and the New York Giants played at the Polo Grounds. This language on ticket stubs would have been limited from the 1919 season when the tax went into effect through the early 1920s.21 Dated Yankees ticket stub samples from the 1922 World Series and later reveal the additional pricing referred to as a “tax” and not a war tax.

Game Numbers on Tickets. In most cases, once the year of the ticket stub is identified, determining the game is generally much easier. Almost all ticket stubs include a number identifying “the home game number,” (e.g., one of 81 current home games) as opposed to the “total game number” (e.g., one of 162 current home and away games) of the respective game. This is important since some ticket stub collectors confuse the number of the home game with the total number of games played as displayed on historic schedules such as at Baseball Almanac. It is also important to mention that American League teams played 154-game schedules until the 1961 season and that the National League schedules were lengthened to 162 games in 1962. However, in some instances, capital letters such as T, DD, etc. were used in the place on the ticket where the game number is typically located (Figure 1). It is known that in at least one instance tickets with a combination of a capital letter and number were used for a playoff game. This is supported by the ticket used by the Boston Red Sox at Fenway Park for the playoff game against the Yankees on October 2, 1978, known as the Bucky Dent game because of his unexpected late-inning home run.22 At this game, a ticket labeled as game E2 was used to grant access to Fenway Park (Figure 4). In addition, it is known that letters were used on tickets to indicate additional print runs of tickets when initial supplies were exhausted. When large single game attendance numbers required additional print runs of tickets, a letter representing the additional print run was added beneath the game number (Figure 5).

Team Names Used on Tickets. When the Baltimore Orioles franchise was moved to New York in 1903, the team name was changed to the Greater New Yorks, while the popular press nicknamed them the Highlanders, to reflect the new environment located at one of the highest elevations on Manhattan Island. The Highlanders played at American League Park, also referred to as Hilltop Park, 1903–12. The earliest known reference referring to the team as the “Yankees” appears in the Washington Post on June 22, 1904.23,24

When the team began play at the Polo Grounds a few blocks away for the start of the 1913 season, the nickname Highlanders no longer fit, due to the lower elevation of the Polo Grounds. In January of 1913, the team officially changed the name of the club to the “American League Baseball Club of Manhattan.” However, early Highlanders and Yankees ticket stubs display at least four different team names.25,26

In addition to the more recent use of the New York Yankees, Inc., other names on early tickets include the New York American Ball Club, the Greater New York Baseball Club of the American League, and the American League Baseball Club of New York. The use of the name American League Baseball Club of New York actually appears on tickets with two different spellings depending on the year issued. On tickets from the 1920s, “American League Base Ball Club of New York” is used with baseball written as two words. Tickets issued later, including some documented in the 1940s, use “American League Baseball Club of New York” with baseball spelled as one word.27

Once the official dates of each of the Yankees’ name changes are documented, the time period the names were used will provide a range of years each was used and subsequently allow ticket stubs to be identified.

Rain Check Language or Advertising on the Front and/or Back of Tickets. Most ticket stubs contain legal language somewhere on the stub. The language is designed to communicate the terms of the relationship between the ticket holder and the sport organization. Over the years, no doubt due to the litigious nature of our society, the legal language appears to have changed often. However, in a few instances the language remained the same while the formatting changed slightly. Something as simple as the words shifting from left justification to being centered may help differentiate one year from another. In some instances, years are actually included as part of the legal language text. An example is tickets issued in 1926, which includes “Sec. 800 d Revenue Act of 1921” in the body of the text. Obviously, we know that tickets that include this language were issued no earlier than 1921.

Advertising on the reverse side of tickets may also help narrow the year they were issued. Some tickets from the 1920s included ads on the back. (See Figure 6) Though it is not yet known what year advertising ceased and legal language became permanent on the back of ticket stubs, the use of different logos or sponsors may be a useful tool in narrowing the dates tickets were issued. For example, existing ticket stub samples indicate that Yankees grandstand tickets in 1923, 1924, 1926, and 1927 had a Canada Dry logo on the reverse side of the ticket. However, in 1925 the backs of the tickets did not include any advertising or legal language. They were completely blank. The Canada Dry logo, or lack of it in 1925, is just another example of how subtle details, used in conjunction with other points of reference, may be used to help identify the year ticket stubs were issued.

Numbers and Letters on Front of Tickets. Many undated grandstand and bleacher ticket stubs 1923–73 include unidentified numbers and letters printed in the area of the stub where the game number is provided. Typically written vertically, these items may include a four or five digit number (Figure 5), a single letter (Figure 5), or a phrase such as Series A, Series B (Figure 1), etc. Once identified, these items may hold some significance in determining the year the ticket stub was issued.

Printing Company. Three different names of printing companies have been identified on Yankees tickets 1923–73. Research is currently being done to see if it is the same company that merged with others, possibly just changed names, or if they are different entities altogether. According to ticket stub samples, the names are The Brown Ticket Corp., M.B. Brown, and Devinne-Brown. Knowing this valuable information can provide a range of years tickets were issued.

Watermarks. Some tickets have a circular watermark of the Yankees red “top hat” logo. Artist Henry Alonzo Keller created this logo for the team in 1947. The logo was introduced for spring training prior to the 1947 season and was used through the 1970s.28,29

The obvious significance of this particular watermark is that any ticket that contains it must have been issued after 1946. This watermark, used in conjunction with the tenure of Larry MacPhail as team president 1945–47, allows tickets issued in 1947 to be easily identified. For example, if a ticket stub contains Larry MacPhail’s replica signature as team president (1945–47), and the Yankees top hot watermark first introduced in 1947, then the ticket stub must be from the 1947 season (Figure 7). Further, since the ticket stub illustrated in Figure 7 is from home game number 8 of the 1947 season, we can cross-reference historical baseball schedules, and with three separate identifiable marks on the stub, it appears that it is from the May 13, 1947, game at Yankee Stadium against the St. Louis Browns.

Length of the Season. The 162-game season was implemented in the American League in 1961 and in the National League in 1962. Prior to that, Major League Baseball played a 154-game season.30 As previously mentioned, all game numbers printed on ticket stubs refer to the number of the home game scheduled that respective season. All teams play half of their games in their home ballpark and the other half in the facilities of their opponents. Therefore, in any one season, no Yankees team would have been scheduled to play more than 77 regular season home games in a season prior to 1961, or more than 81 regular season home games during or later than the 1961 season. Subsequently, any Yankees ticket stubs illustrating a home game number higher than 77 must be from the 1961 season or later.

Handwritten Dates on Ticket Stubs. From time to time undated ticket stubs will appear with the date handwritten on the front or back of the stub (Figure 8). These stubs are sometimes accompanied with a program or other piece of memorabilia from the game referenced.

Though additional resources provided with a ticket stub may be helpful, it is recommended that researchers proceed with extreme caution when relying on dates handwritten on undated ticket stubs. Researchers should rely on multiple techniques identified in this manuscript to identify or narrow the date range. The more pieces of the puzzle that fit together the more confident researchers may be that a ticket stub is authentic. Short of testing the ink for precise dating, which would be expensive and likely only yield a range of dates as well, it is almost impossible to verify a handwritten date on an undated stub. Due to the explosion of the sports memorabilia industry, collectors and researchers should be wary of handwritten dates especially if the date coincides with a historically significant game.

Implications of the Study

The implications of this study are significant. The Yankees are one of the highest profile sports teams in the world. In addition, they have a rich tradition of success, winning championships and having players voted into the National Baseball Hall of Fame. If a sports franchise like the Yankees, with such a rich historical past, has hundreds perhaps thousands of undated ticket stubs available in the sports memorabilia market, how many other teams in professional sports may have issued similar tickets? The findings of this study might not only be significant to Yankees, but may be applied to other teams with undated tickets in all sports.

Future Research

As with any preliminary study, the process of discovery is ongoing. The goal of this initial project is to generate discussion about the historical importance of ticket stubs in all sports, and, in the process, begin to identify as many undated Yankees grandstand and bleacher tickets as possible. Remaining ticket stubs are part of sports history and a tangible link to the games they represent. Some ticket stubs may be from games more significant than others. However, collectors deserve to have an opportunity to decide for themselves, which are most valuable. Since it is documented that other sports franchises, such as the Philadelphia Phillies, issued tickets without dates for at least a period of time (Figure 3), the author hopes that identification techniques introduced in this paper may be used to identify historical ticket stubs for other professional sports franchises not just in baseball, but for all applicable sports.

In conclusion, it is important to reiterate that many of the techniques described in this manuscript only limit the dates of ticket stubs to a range of particular years. Few alone can identify the year and date of a particular ticket stub. The combination of multiple criteria provides redundancy and is the recommended method for identifying undated ticket stubs.

DR. JAMES REESE is an associate professor in the sport management program at Drexel University in Philadelphia. Before beginning a career in higher education, Dr. Reese worked as a ticket administrator for the Denver Broncos from 1996 to 1999, where he had an opportunity to assist in planning and executing ticket operations and ticket sales for Super Bowls XXXII and XXXIII. Dr. Reese’s research interests include ticket operations and ticket sales and college athletic reform.

Notes

1. Collectors Weekly, “Collectible Ticket Stubs, Accessed October 30, 2012, www.collectorsweekly.com/paper/ticket-stubs.

2. TheFreeDictionary Online, s.v. “Ticket stub,” Accessed January 9, 2013, www.thefreedictionary.com/ticket+stub.

3. Dan Busby, “Why and How to Collect Baseball Tickets,” November 13, 2002, Baseball Ticket Man, www.baseballticketman.com/Default.aspx?PageName=WhyAndHowToCollectBaseballTickets].

4. Joe Orlando, Collecting Sports Legends—The Ultimate Hobby Guide (Irvine, CA: Zyrus Press, 2008), 355.

5. Jim Capobianco, “Collecting Tips: Sports Tickets and Stubs,” September 22, 2012 http://reviews.ebay.com/Collecting-Tickets-and-Stubs?ugid=10000000000920191.

6. Orlando, Collecting Sports Legends, 355.

7. Capobianco, “Collecting Tips: Sports Tickets and Stubs.”

8. Busby, “Why and How to Collect Baseball Tickets.”

9. Capobianco, “Collecting Tips: Sports Tickets and Stubs.”

10. Orlando, Collecting Sports Legends, 355.

11. Ibid.

12. Dave Anderson, The New York Times Story of the Yankees: 382 Articles, Profiles, & Essays from 1903 to the Present (New York, NY: Black Dog & Leventhal Publishers, Inc., 2012), 52.

13. Mark Vancil and Mark Mandrake, eds., One Hundred Years: New York Yankees an Official Retrospective (Chicago, IL: Rare Air Media, 2002), 13.

14. Anderson, The New York Times Story of the Yankees, 52.

15. Vincent Luisi, Images of Sports: New York Yankees the First 25 Years (Charleston, SC: Arcadia Publishing, 2002), 103.

16. Les Krantz, Yankee Stadium: A Tribute (New York, NY: Harper Collins, 2008), 145.

17. James Reese and Chris Moberg, “An exploratory study of the college transplant fan,” The SMART Journal, 41(1), p. 28. The purchasing benefits of brand loyalty were addressed in a PowerPoint presentation obtained from the Charlotte, NC office of the National Association for Stock Car Auto Racing (NASCAR) dated September 18, 2008.

18. George Michael, “Identifying Mystery Photos,” Baseball Research Journal, 33, 2004, 36–46.

19. Yankees History, “Yankees timeline,” Accessed November 6, 2012. http://newyork.yankees.mlb.com/nyy/history/index.jsp

20. Yankees.com, “All-Time Owners,” Accessed November 6, 2012. http://mlb.mlb.com/nyy/history/owners.jsp; Yankees History, “Yankees timeline,” http://newyork.yankees.mlb.com/nyy/history/index.jsp

21. “PRICE OF BASEBALL TICKETS ARRANGED; Internal Revenue Official Suggests Scale for Use While War Tax is In Force,” The New York Times, February 12, 1918.

22. Phil Pepe, The Yankees: An Authorized History of the New York Yankees (Lanham, MD: Taylor Trade Publishing, 2003), 197.

23. Luisi, Images of Sports, 14.

24. Anderson, The New York Times Story of the Yankees, 22.

25. City of New York Parks & Recreation, “Coogan’s Bluff,” Accessed January 21, 2013. www.nycgovparks.org/parks/highbridgepark/highlights/11107; Phillip J. Lowry, Green Cathedrals: The Ultimate Collection of All 271 Major League and Negro League Ballparks Past and Present (Reading, MA: Addison Wesley, 1992), 195; James Renner, “Coogan’s Bluff and the Polo Grounds,” accessed January 21, 2013, www.hhoc.org/hist/ coogans_bluff_p.htm; Lawrence S. Ritter, Lost Ballparks: A Celebration of Baseball’s Legendary Fields (New York, NY: Viking Studio Books, 1992), 158.

26. Anderson, The New York Times Story of the Yankees, 22.

27. Ibid, 19.

28. David Stout, “Henry Alonzo Keller, 87. Artist of the Yankees top hat logo,” The New York Times, June 28, 1995.

29. Ibid; Biography of Henry Alonzo (Lon) Keller 1907–1995, “About the Artist,” Accessed January 21, 2013, www.lonkeller.com/biography.htm.

30. Anderson, The New York Times Story of the Yankees, 253.

31. Mark Gallagher, The Yankee Encyclopedia, 315.

32. Gallagher, The Yankee Encyclopedia, 317.

33. Gallagher, The Yankee Encyclopedia, 321.

34. Gallagher, The Yankee Encyclopedia, 323.

35. Gallagher, The Yankee Encyclopedia, 325.

36. Gallagher, The Yankee Encyclopedia, 326.

37. Gallagher, The Yankee Encyclopedia, 339.