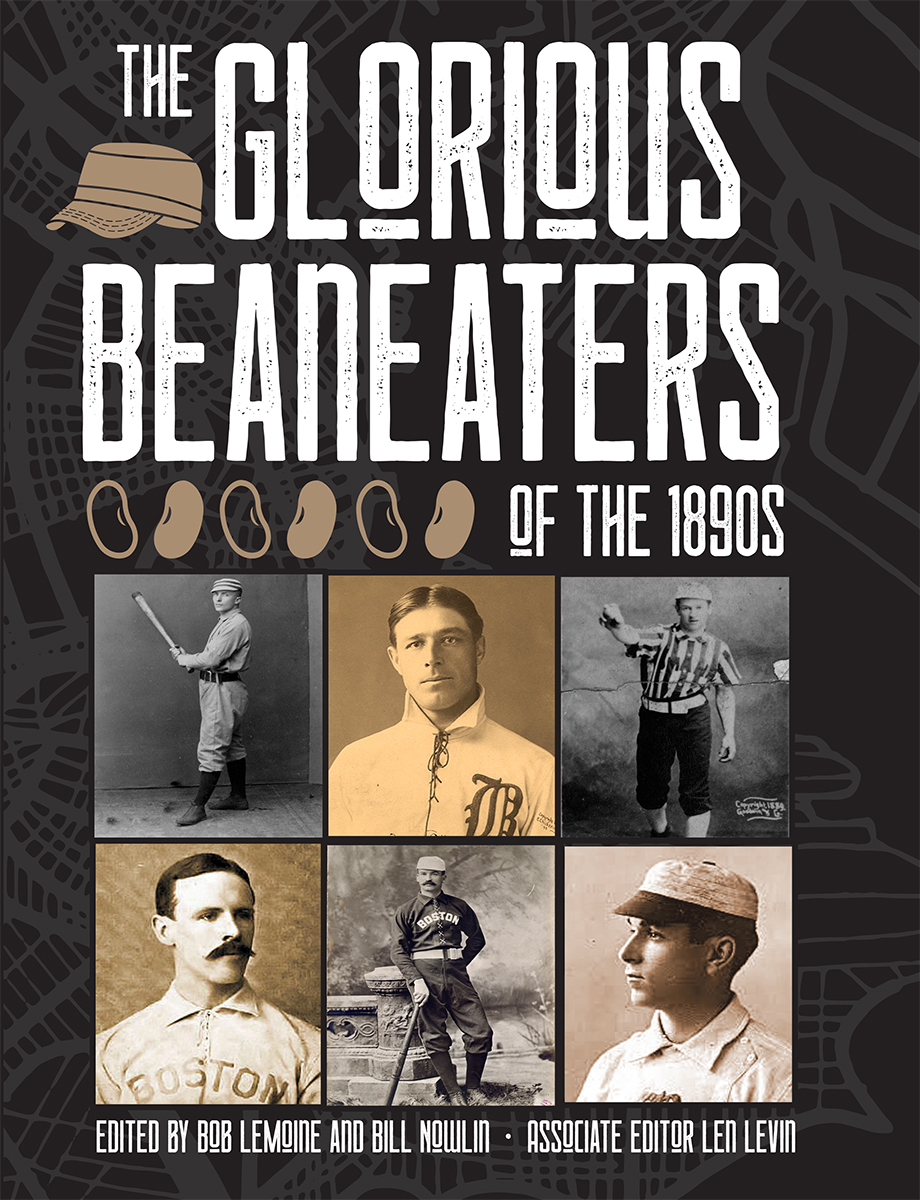

Introduction: The Glorious Beaneaters of the 1890s

This article was written by Bob LeMoine

This article was published in 1890s Boston Beaneaters essays

“Long ago when the team was known as the Beaneaters.”

“Long ago when the team was known as the Beaneaters.”

On Wednesday afternoon, June 17, 1953, at Milwaukee’s County Stadium, Warren Spahn, one of baseball’s greatest left-handed pitchers, was on the mound for the Milwaukee Braves to take on the visiting Philadelphia Phillies. While the veteran Spahn already had a celebrated career with four 20-plus-win seasons, this was only his third start in Milwaukee. Spahn had pitched in Boston for the previous decade for a franchise that dated back to 1871. The club had suddenly and unceremoniously announced its move to Milwaukee during spring training, ending 82 years of a National League club in Boston. While there was excitement in the Brew City over its new franchise, which would lead the NL in attendance and see a World Series title in 1957, there was the empty shell of Braves Field in Boston and the now-forgotten landmark where the South End Grounds once stood amid the roar of streetcars.

Probably few fans noticed the presence of a guest from Oregon who came to watch the Braves that day. He owned a walnut ranch out there, but Wisconsin was his home state, where he learned to play baseball in the cow pastures. He was Billy Sullivan Sr., a former major-league catcher famous for his time with the Chicago White Sox in the first decade of the twentieth century. Sullivan was of a small few still around who had played in the nineteenth century, and he had played for Boston in 1899. When he died in 1965, just a few days shy of his 90th year, Sullivan was the last living member of Boston’s baseball dynasty of the 1890s.

“I’m a Braves rooter because I played with the Braves long ago when the team was known as the Beaneaters,” Sullivan told Sam Levy of the Milwaukee Sentinel. Even after a half-century, those days were still fresh in his mind, including those of his batterymate, Kid Nichols, who he said was the fastest pitcher he ever caught. “The Kid was one of the best,” he said.1

More than a century has passed since the “glorious Beaneaters” era of Boston’s baseball history in the 1890s. Sullivan actually wasn’t a major factor in that history, having played only 22 games for Boston in 1899 and not having experienced the pennant seasons of 1891-1893 and 1897-1898. The franchise now lives on in Atlanta, but it’s doubtful you ever hear reference made to the Beaneaters. Their stories are largely forgotten by all but the serious follower of baseball history. Yet, while Boston would soon have a second baseball club that would capture the hearts of New England, never again would there be such dominance over a decade as the Beaneaters accomplished.

Nine of these players would one day become hall of famers. There was John Clarkson, whose mental health issues late in life overshadowed a truly remarkable pitching career which saw him win 327 games in a 10-year span. Kid Nichols was Boston’s ace on the mound during the era. Despite seven seasons of at least 30 wins and 362 career wins he was “pushed into baseball’s medieval past” in the words of historian Bill James. There were the “Heavenly Twins,” Hugh Duffy and Tommy McCarthy, who roamed the Boston outfield with speed and grace. Yet, no one could top the speed of Sliding Billy Hamilton, whose career stats in walks, runs, steals and batting average still make the modern researcher shake their head. Jimmy Collins won pennants with both Boston franchises and has been dubbed by Charlie Bevis as “the patron saint of today’s Red Sox Nation.” Vic Willis was just a rookie when the Beaneaters dynasty was winding down, but his 25 wins helped propel them to the 1898 pennant and he enjoyed seven more seasons of at least 20 wins. And what can you say about King Kelly, baseball’s true first superstar whose exploits on and off the field elevated the game into the world of popular culture? Sporting Life called Frank Selee “a thorough baseball general” and he exhibited his leadership in guiding these Beaneaters to five pennants throughout the 1890s.

If you’re a baseball fan but don’t recognize these names, you’re not alone. The Baseball Hall of Fame itself seemed to forget these legends. They were part of a forgotten era as America steamed into the twentieth century. Fortunately, the game eventually remembered their names and their times. Some were inducted while in their golden years, but time ran out on others who never received the recognition they deserved. Now enshrined in the Hall, their stories live on, enabling a group of SABR researchers to delve deeper into who they were and what the game was like.

But we have to ask, what is a Beaneater?

“Beaneaters” was not even an official nickname for the team, but one coined by sportswriters, as Charlie Bevis wrote, “to drum up more interest among readers than by continuing to use the bland ‘Bostons’ term.”2 Yet, the name stuck and the Beaneaters and the 1890s remain a distinct era in Boston’s baseball history.

This book is the result of SABR researchers who believe the Glorious Beaneaters era of the 1890s is a story worth telling. We attempt to do so by telling the stories of the men who played for Boston and some of the interesting games they were involved in. “The tumultuous 1890s witnessed a player revolt against high-handed and monopolistic management,” wrote baseball historian John Thorn, “epitomized by a cap on salaries, followed by a nearly ruinous contraction from three major leagues to one 12-team circuit. The national economy suffered a panic in 1893 and a sluggish recovery thereafter; baseball attendance dwindled; and the lack of postseason interleague competition after 1890 (as there had been since 1884) was sorely felt. The game was in a period of consolidation, or hibernation, or stagnation; one’s perspective depended upon whether he were an owner, fan, or player.”3 Legendary manager Connie Mack remembered that era firsthand as “a turbulent decade of the so-called roughhouse days in baseball. The Boston Beaneaters were ready for any fray, ever willing to take on the pugnacious Baltimore Orioles and give them a dose of their own medicine.”4

We hope this book will give you, the reader, an enjoyable journey into the 1890s and the era of the Glorious Beaneaters.

BOB LeMOINE was previously co-editor of Boston’s First Nine: The 1871-75 Boston Red Stockings (SABR, 2016). He has specific interests in Boston’s baseball history, the 19th Century, and the Negro Leagues, but he often jumps into any SABR project. Bob lives in New Hampshire and works as a high school librarian and adjunct professor.

- Read more: Find all essays from The Glorious Beaneaters of the 1890s in the SABR Research Collection online

- BioProject: Find biographies of players from the 1890s Boston Beaneaters at the SABR BioProject

- Games Project: Find articles on the 1890s Boston Beaneaters at the SABR Games Project

- E-book: Click here to download the e-book version of The Glorious Beaneaters of the 1890s for FREE from the SABR Store. Available in PDF, Kindle/MOBI and EPUB formats.

- Paperback: Get a 50% discount on The Glorious Beaneaters of the 1890s paperback edition from the SABR Store ($17.99 includes shipping/tax; delivery via Kindle Direct Publishing can take up to 4-6 weeks.)

Notes

1 Sam Levy, “Billy Sullivan, Sr., Here to Watch ‘His Braves,’” Milwaukee Sentinel, June 18, 1953: L9.

2 Charlie Bevis, Red Sox vs. Braves in Boston: The Battle for Fans’ Hearts, 1901-1952 (Jefferson, North Carolina: McFarland, 2017), 50.

3 John Thorn. Total Baseball 6th ed. (New York: Total Sports, 1999), 6.

4 Connie Mack, “Roughhouse 1890’s Recalled by Connie,” Philadelphia Inquirer, April 4, 1950: 34.