Jackie on Stage: Jackie Robinson and Vaudeville in 1947

This article was written by Adam Berenbak

This article was published in Not an Easy Tale to Tell: Jackie Robinson on the Page, Stage, and Screen (2022)

Just across Florida Avenue, in the shadow of Griffith Stadium, home to both the Senators and the Grays in 1947, sat the Sportsman Inn. Joe Hurd, the new proprietor, had recently purchased the establishment from longtime DC radio DJ and baseball announcer Hal Jackson, who was in the process of moving to New York. On this occasion Hurd was hosting a party along with the District Theaters Group, owners of the Howard Theater, which sat across T street from the Sportsman Inn and still keeps its doors open to this day. The party included longtime vaudeville acts Tiny Bradshaw, Butterbeans and Susie, and a host of other Howard stage regulars. But the guest of honor, Jackie Robinson, had achieved stardom on a different stage that year.1

Just across Florida Avenue, in the shadow of Griffith Stadium, home to both the Senators and the Grays in 1947, sat the Sportsman Inn. Joe Hurd, the new proprietor, had recently purchased the establishment from longtime DC radio DJ and baseball announcer Hal Jackson, who was in the process of moving to New York. On this occasion Hurd was hosting a party along with the District Theaters Group, owners of the Howard Theater, which sat across T street from the Sportsman Inn and still keeps its doors open to this day. The party included longtime vaudeville acts Tiny Bradshaw, Butterbeans and Susie, and a host of other Howard stage regulars. But the guest of honor, Jackie Robinson, had achieved stardom on a different stage that year.1

The most popular narrative in the life of Jackie Robinson centers around the year 1947, when he ended segregation in the National League. In that narrative, the year involves his momentous April 15 game, when he became the first Black man to play the sport at the major-league level since the 1880s, leading the Dodgers to a thrilling pennant chase and victory, becoming the first-ever Black player in a major league World Series, and culminating in his being awarded the first ever Rookie of the Year award. Though some biographies touch upon the 1947 postseason, including his salary negotiations and initial foray into film, few delve deeply into his post-rookie campaign activities. In his autobiography, Robinson makes no mention of this time, nor does Rachel Robinson in her Intimate Portrait.2 The only mention of the offseason touches on all of the delicious food he ate on the southern speaking tour in January of ’48, and how it led to him showing up to spring training overweight, which is where most of the narratives of his life pick back up.3

However, during October and November, Robinson traveled the US as part of a vaudeville act that toured traditionally African-American entertainment venues and may be referred to as Black vaudeville. Though baseball’s biggest stars had been supplementing their income as vaudeville acts going back over half a century, Jackie Robinson’s brief time on the circuit was scrutinized very much like his experience on and around the diamond during the first nine months of 1947, fraught with implications surrounding integration; his role as a Black ballplayer and exponent for social justice; as well as his standing in the Black community.

It begins with the ball dropping into Al Gionfriddo’s expertly positioned glove. Jackie Robinson had driven in Pee Wee Reese in the third and crashed into Phil Rizzuto on second, providing some of the run support that made Gionfriddo’s miraculous snag of Joe DiMaggio’s monster smash all the more important, as it saved the game and set up a Game Seven of the World Series.4 It was another first for Robinson in a season of firsts, but it would prove to be a letdown, as he went 0-for-4 and the Dodgers lost the game and the Series, the start of a near decade of Brooklyn frustration.5 More important to the Dodger players was that they had lost out on the winners share, though they did take home a bonus that, in some cases, substantially supplemented their salary.

In Robinson’s case, the Series losers share of roughly $4,200 nearly equaled his rookie salary of $5,000, the league minimum.6 While papers such as the Richmond Afro American were quick to address that he had received the same share as his White teammates who had contributed as fully as he had, the total amount he had earned as a pro ball player during the full 1947 season fell far short of his contributions to the team and the game.7 This was a problem not just of basic labor issues of major-league baseball at that time, but also of race and labor in the post-war period.

As so many Negro Leaguers, major leaguers, minor leaguers, and other pros had done since the advent of professional baseball, Jackie Robinson sought a livelihood outside of baseball once the season was done. While the majority of those players had found their sources of income in working-class labor and non-baseball jobs such as florists, policemen and running liquor stores, as well as winter ball south of the border, Robinson sought to utilize his notoriety and capitalize on his celebrity in the same fashion as other superstars had done as long as the game had existed. Given his position as a trailblazer, it would be a decision made under a microscope.

Though ballplayers had taken to the stage as early as the 1860s, one of the first well known acts was Cap Anson, cited so often as one of the primary drivers of segregation in baseball. After having appeared on Broadway once or twice in the 1890s, he made his debut on the vaudeville circuit in 1913, at the same time that more current stars of the game like John McGraw, Waite Hoyt, Christy Mathewson and Rube Marquard were moonlighting there as well.8

One reason for this was that vaudeville, as a forum, was relatively new at the turn of the century. It had its origins in Normandy during the sixteenth century, though in America the vaudeville of the twentieth century was much more closely related to traveling variety and medicine shows as well as the “concert saloons” of 1840’s New York and Boston’s Vaudeville Saloon.9 The more modern iteration had begun in Boston in the late 1880s and offered more of a long-format variety show as an alternative to the large minstrel shows so popular on stages. By 1900 there were vaudeville houses all over the US that included both Black and White acts, as well as many of the minstrel acts it had supplanted.10 For the most part, the main “act” of a famous ballplayer was to appear on stage and answer questions or read off a few quotes. Rarely was any singing or dancing performed – they were there just to be themselves.11

What became known as Black vaudeville began around the same time. While many Black performers joined vaudeville shows that included blackface and other hallmarks of minstrelsy performed before mostly White audiences, many others sought out Black audiences in churches and tents, as well as black-owned theaters known as the “Dudley Circuit,” named for Sherman Dudley, or White owned T.O.B.A. (Theatre Owners Booking Association). By the 1920s and ‘30s, as Black business grew and became more profitable, a more expansive Black vaudeville circuit, sometimes referred to as the “Chitlin’ Circuit,” had developed, stationed at large venues such as the Apollo, in New York, and the Howard Theater, in Washington D.C., that had been built for that purpose.12

In October of 1947, after the announcement of his Rookie of the Year award, all the news about Jackie Robinson centered on his endorsements, most famously for Bond Bread, as well as a contract with General Artists Corporation.13 GAC had arranged for him to earn extra income from a book as well as theatrical ventures, stops on the vaudeville circuit on his way to the West Coast, where he and his family would not only spend the holidays, but bring him close to film studios in preparation for a film produced by Herold Pictures, Inc called Courage, purportedly about juvenile delinquency.14 The film never materialized, but his cross-country tour generated both the needed income unattainable through his salary and World Series loser’s share, as well as a never-ending cavalcade of press and publicity, good and bad.

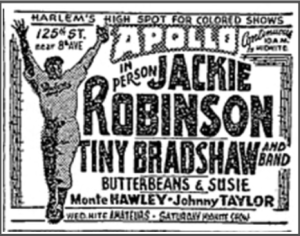

The press focused on the money he made from his off-season ventures – the many divergent accounts slyly implying greed as a motive, a narrative found often throughout the history of baseball players income. A few did so in aggressive terms that suggested racist overtones: “And the already wealthy Robinson isn’t through. He is now sacking up the gold on vaudeville tours and personal appearances.”15 After he appeared on a few radio programs, it was announced that he would begin his string of vaudeville appearances at the Apollo Theater in Harlem, before hitting the stage at the Howard Theater in Washington, the Regal Theater in Chicago, and finally the Million Dollar Theater in Los Angeles.16

Much like John McGraw and myriad other ballplayers before him, his “act” was simply to show up and answer questions on stage, as he had done in his radio appearances.17 Supporting him was Tiny Bradshaw and his band, along with longtime vaudeville comedians Butterbeans and Susie, and finally dancing acts like the Harris Brothers and the Three Hall Sisters. He was later joined by Monte Hawley.18 As he was being celebrated for integrating baseball, Jackie Robinson was still scheduled to begin a tour on the chitlin circuit at the Apollo, a landmark that “after the demise of the Harlem nightclubs… continued the tradition of black vaudeville.”19 Though the Apollo was the apex of the Black stage, those who viewed Jackie as an integrationist may have perceived this as a step in the wrong direction.

On Saturday night, October 18, in front of a packed crowd in the Apollo, Robinson made his stage debut. Leading up to the performance, reporters had alternately highlighted the income he would attain as well as given generally positive reviews of his willingness to get on stage, and the quality of his supporting acts. Yet, nearly as soon as he had exited the stage, the critical reviews reflected the worries that a proximity to the minstrel tradition would cheapen his accomplishments, balanced with the desire to celebrate him properly. One of the first reviews came from the oldest black newspaper, the New York Amsterdam News. “The thought grows on you as you watch, ‘What the hell is Jackie Robinson doin in this?’ Clearly, ‘money’ was the right answer, but ‘the idea persisted that there should be another way for him to earn the income he so richly deserves.’”20 Doris Calvin, writing in the Baltimore Afro American, criticized the show itself as bringing Jackie “down to a far-beneath-him capacity,” but wrote, “We’re not saying Jackie shouldn’t have made this tour. Too many proud folks want to see him in the flesh. But there’s much room for improvement. The script, as it now stands, should be burned and the writer shot at sunrise. The type of material Jackie needs is on the order of ‘We the People.’ In which he tells of his own life in a fascinating, idolized manner.”21

An advertisement for Robinson’s October 1947 performance at the Apollo.

The White press simply lauded the “hundreds upon hundreds of Harlemites” attending the show, claiming he had a “fine stage personality and appears to be just at home on the stage as first base.”22 And one of the few of his biographers to describe the tour, Arnold Rampersad, would focus much on Rachel’s perception of the act, who “had reservations about this latest gambit. It seemed risky especially since ‘Jack couldn’t sing, and he was only a fair dancer. I couldn’t imagine what he was supposed to do.’”23 Another would point out that “some questioned if his appearance in a poorly run black vaudeville troupe undermined the public image of black dignity he had bolstered,” but that “such criticism…only amplified the special burden for his race that he found himself carrying and the limited career opportunities for black males in postwar America.”24

The reaction reflected both the importance for the community to celebrate him as an integrationist and hero, along with a worry that association with Black vaudeville would taint that role.

The week of the 25th saw productions of No Exit in Washington D.C., along with performances by Francescatti, Ted Lewis and his band, and movie house showings of Olivier’s Henry V, Crossfire, and Forever Amber.25 And at the Howard Theater, Jackie Robinson and his traveling show. The Robinson’s stayed with local businessman Arthur Newman26 while Robinson performed at the Howard, appearing on stage five times a day including the midnight “Night Owl Jamboree.”27 By the time of the party at the Sportsman Inn, it seemed that his publicity tour was in full swing, mixing weekly galas and performances as well as a lot of interaction with the press, who were included as guests at the Sportsman.

On the way to Chicago Jackie and Rachel Robinson, who were traveling with Jackie Jr., stopped church banquet in his honor at the White Rock Baptist Church.28 While there Robinson repeated a comment he had made during several press interviews during the tour – that he would spend only three more seasons in the majors.29 Whether these were tactics aimed at gaining leverage with Branch Rickey in preparation for his 1948 salary negotiation that would take place in January, or simply his genuine feelings is not certain – later on the tour he would claim to have been misquoted. At the same time the Richmond Afro American was running a contest in its papers – asking readers who was more popular, Robinson or Joe Louis.30 Regardless of the outcome, his position as the leading role model in the Black community was cemented.

Prior to Robinson’s appearance in Chicago, the Defender ran a story about Abe Saperstein announcing he had offered Robinson a $6,000 contract to play basketball for Chicago’s Harlem Globetrotters, at that moment coming into their own as a showcase of African-American sports talent.31 Saperstein was intimately involved with Black baseball beginning in the late 20’s with his affiliation with barnstorming tours and the Negro League East-West All-Star Game. Robinson’s breaking of the color barrier was rejoiced by the Jewish community and seen as “a symbolic representation of their experience of assimilation into American society in the era immediately following World War II.”32 Yet Saperstein’s role as part of a larger Jewish ownership stake in Black baseball was viewed as complicated, alternately as supportive and exploitative, and seen as promoting a “brand of comedic baseball based on vaudeville” that “played a role in making these ‘showman’ black players poor candidates for the serious game of major league baseball.”33 Though there is no record of Robinson’s response, Saperstein’s offer illustrates the challenges Robinson faced in deciding how to manage his status as role model, athlete, and entertainer.

Again, he and his wife were feted, this time at the Savoy Ballroom. Robinson took the occasion to honor Rachel, who was also presented with the “Smartest Woman of the Year” award.34 Though the Savoy was a place where “race and class boundaries were blurred in ways that were undreamed of in other settings,” Robinson continued to be honored mainly by Black organizations.35As the White press lauded him they still continued to speculate about his income from the tour – some said $100,000, Ed Sullivan quoted $25,000 – and generally posed him as an outsider.36 Booked into the Regal Theater, another stop on the “Chitlin’ Circuit,” for the week in Chicago, Robinson was presented with his Rookie of the Year Award by the Chicago Chapter of the Baseball Writers of America there on November 12.

On their drive to Los Angeles there was a small detour scheduled to take place in Oklahoma City, along with a meet-and-greet organized by sportswriter Fay Young. Months later an article came out in the Chicago Defender accusing Robinson of missing the gathering and disappointing a host of children eager to meet their hero.37 Though he apologized and explained that he had been unaware of the meeting when they had passed through the city, he also criticized the tone of the reporting, it was another example of his complicated relationship with the Black press which peaked after his 1948 Ebony article criticizing the Negro Leagues and his appearance before the U.S. Congress’ House Un-American Activities Committee (HUAC) the following year, where some accused him of selling out his community.

On Tuesday, November 18, Robinson and his tour arrived at its destination. Right away he went to work, attending a press junket at the Sports Club on South Hill before headlining the opening night of the Los Angeles leg at the Million Dollar Theater. The lineup was nearly the same, featuring Robinson and Monte Hawley, Johnny Taylor and Gerald Wilson, along with Little Miss Cornshucks, Mabel Scott, and Kay Starr, along with Herb Jefferies. They played the week before another well-known Robinson, Bill “Bojangles” Robinson, took over the stage beginning the 25th. 38

The following week a “welcome home” reception was held at the First Methodist Church, with invitations sent to Happy Chandler, Branch Rickey, and fellow local National Leaguer Ralph Kiner.39 There was no film, and it was rumored that final say laid with Rickey, who was “embarrassed” by the tour.40 If so, it adds another layer to Robinson’s decision making going forward, about future ventures on stage and screen, and how Rickey attempted to drive that narrative. The Jackie Robinson Story, made only a few years later, would be praised as groundbreaking in film integration, tapping into “cultural daydreams of American life, as Americans, both black and white, contemplated the possibilities of a society where blacks and whites would meet and interact completely as social equals.”41

After the holidays the Robinsons began the slow journey east, this time on the ‘southern tour’ that gained so much attention for what Robinson gained in pounds. He continued the format of appearing publicly with music, though in a much less structured way, appearing at Wright’s Playhouse in Waco Texas with an a capella choir called the Samuel Huston Collegians,42 then with the Billy Banks orchestra in Chilhowee Park in Knoxville,43 then Nashville with The 5 Bars at War Memorial Auditorium,44 all while finding time to referee a “colored amateur boxing tournament’ in Knoxville,45 negotiating his salary with Branch Rickey, and eating too much good southern food. The challenges facing Jackie Robinson during the entirety of that 1947 journey, from Ebbets Field to vaudeville, epitomize the demands and triumphs of integration on so many different stages.

ADAM BERENBAK is an archivist with the National Archives Center for Legislative Archives in Washington, DC. He has been a member of SABR for over a decade and his research focuses on the history of baseball in Japan, on which he has published articles in the SABR Journal and Our Game, curated an exhibition with the Japanese Embassy’s Cultural Center in DC, and contributed to a number of articles and books. He has also published several essays on other topics related to baseball history in the SABR Journal, Prologue, Zisk, and an exhibition in conjunction with the Museum of Durham History and the Durham Bulls Athletic Park. His work will also be featured in upcoming SABR books on Jackie Robinson and US Tours of Japan.

Notes

1 Louis Lautier, “Capital Spotlight,” Richmond Afro American, November 1, 1947: 3.

2 Rachel Robinson, with Lee Daniels, Jackie Robinson: An Intimate Portrait (New York: Abrams, 1996).

3 Jackie Robinson, I Never Had It Made (New York: Putnam, 1972).

4 John Drebinger, “Dodgers Set Back Yankees 8-6 For 3-3 Series Tie,” New York Times, October 6, 1947: 1.

5 “Baseball Reference” https://www.baseball-reference.com/boxes/NYA/NYA194710060.shtml

6 “Jackie’s Series Share Estimated At $4,200,” Richmond Afro American, October 11, 1947: 14.

7 “Jackie’s Series Share Estimated At $4,200”

8 Elizabeth Yuko, “When Baseball Players Were Vaudeville Stars,” Atlantic, April 6, 2017, https://www.theatlantic.com/entertainment/archive/2017/04/when-baseball-players-were-vaudeville-stars/521835/

9 Frank Cullen, Florence Hackman, Donald McNeilly, Vaudeville Old & New: An Encyclopedia of Variety Performances in America (New York, London: Routledge, 2006), xi.

10 John Strausbaugh, Black Like You: Blackface, Whiteface, Insult & Imitation in American Popular Culture (New York: Jeremy P. Tarcher/Penguin, 2006), 129.

11 “When Baseball Players Were Vaudeville Stars.”

12 Strausbaugh Black Like You, 129.

13 “Jackie Robinson Prefers Bond Bread,” Richmond Afro American, October 11, 1947: 11.

14 Jack O’Brian, “Broadway,” Sandusky Register Star News, October 13, 1947: 4.

15 Al Lightner, “Sportslightner,” Statesman Journal, October 12, 1947: 14.

16 Danton Walker, “Broadway,” Evening Independent, October 9, 1947: 3.

17 “Robinson Packs Stage Wallop at Apollo Theater,” Brooklyn Eagle, October 24, 1947.

18 “Jackie Robinson Launches Theater Tour at NY House,” Pittsburgh Courier, October 18, 1947.

19 Brenda Dixon Gottschild, Waltzing in The Dark: African American Vaudeville and Race Politics in the Swing Era (New York: Palgrave, 2002).

20 Arnold Rampersad, Jackie Robinson: A Biography (New York: Knopf, 1997), 190.

21 Dolores Calvin, “They Made Him A Bum?” Baltimore Afro American, November 1, 1947: 6.

22 “Robinson Packs Stage Wallop at Apollo Theater.”

23 Rampersad, Jackie Robinson: A Biography, 190.

24 J. Christopher Schutz, Jackie Robinson: An Integrated Life (Lanham, Boulder, New York, London: Rowman & Littlefield, 2016).

25 Advertisements, The Washington Post, October 26, 1947.

26 Lautier, “Capital Spotlight,” 3.

27 “Robinson To Appear on Howard’s Stage,” Richmond Afro American, October 18, 1947: 15.

28 “Jackie Tells of Ambition to Help Boys,” Richmond Afro American, November 8, 1947: 3.

29 “Jackie Robinson Plans Retirement in 3 Years,” The Washington Post, October 25, 1947: 14.

30 Sam Lacy, “From A to Z with Sam Lacy,” Richmond Afro American, November 15, 1947: 14.

31 “Globetrotters Make for Jackie Robinson,” Chicago Defender, October 4, 1947.

32 Rebecca T. Alpert, Out of Left Field: Jews and Black Baseball (Oxford, New York: Oxford University Press, 2011).

33 Alpert, Out of Left Field.

34 “Robinson Lauded: Jackie and Wife Honored in Chicago,” Rich mond Afro American, November 15, 1947: 16.

35 Gottschild, Waltzing in The Dark.

36 Ed Sullivan, “Men and Maids and Stuff at Broadway and 42nd St.,” Hollywood Citizen-News, October 27, 1947: 18.

37 “Dodgers’ Jackie Robinson Denies Oklahoma Story,” Alabama Tribune, December 24, 1947: 1.

38 “The Weekly Newsreel,” California Eagle, November 20, 1947: 23.

39 “Civics Bodies to Honor Jackie Robinson at Reception Wednes day,” Metropolitan Pasadena Star-News, November 23, 1947: 43.

40 Herbert Goren, “Jackie Robinson Increases Bank Roll Between Seasons,” The Muncie Star Press, November 30, 1947.

41 Gerald Early, “Jackie Robinson and the Hollywood Integration Film,” in Jackie Robinson: Between the Baselines, ed. Glenn Stout and Dick Johnson (San Francisco: Woodford Press, 1997).

42 “Jackie Robinson to be Interviewed by Maxey Here Thursday Night,” The Waco News-Tribune, January 18, 1948: 13.

43 “Robinson to Show Here With Band,” Knoxville Journal, January 25, 1948: 17.

44 “Jackie Robinson, Rookie of the Year, in Person With ‘The 5 Bars’,” Nashville Banner, February 4, 1948: 15.

45 “Negro Boxing Meet Opens Monday Night,” Knoxville Journal, February 22, 1948: 17.