Jackie Robinson and the Decline of the Negro Leagues

This article was written by Nathan Bierma

This article was published in Jackie Robinson: Perspectives on 42 (2021)

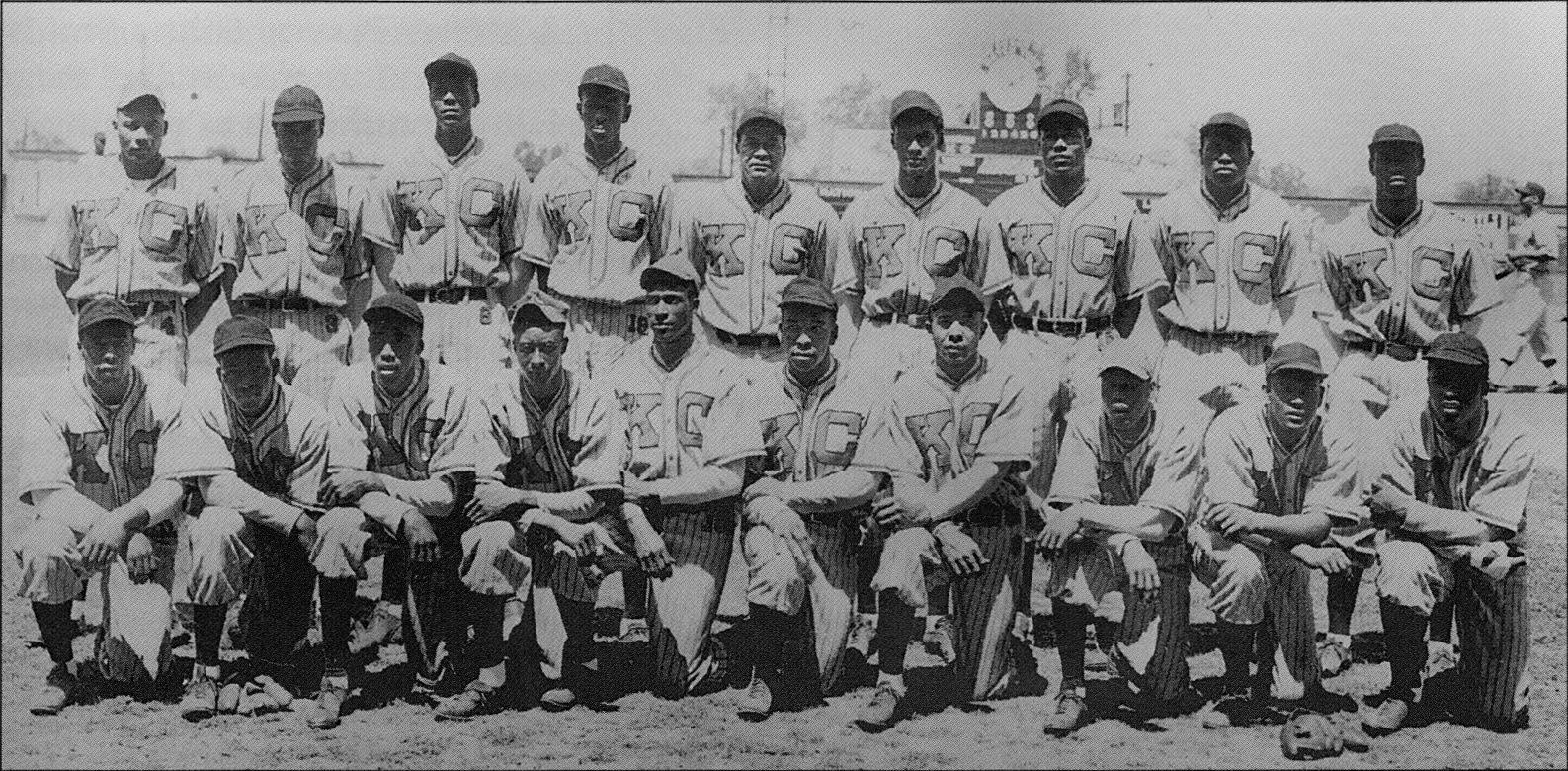

A portrait of the 1945 Kansas City Monarchs of the Negro American League. Jackie Robinson batted .375 in 34 games for the Monarchs before he was signed by the Brooklyn Dodgers in October. (SABR-RUCKER ARCHIVE)

Jackie Robinson’s breakthrough with the Brooklyn Dodgers was a triumph for the integration of baseball and a death sentence for the Negro Leagues. Once the barrier to entry for the top Black ballplayers finally and justly fell, the leagues that used to be the only place to see them play struggled to survive.

The ambivalence of cheering integration but lamenting the fate of once-thriving Black-only institutions was growing in the mid-twentieth century. “The gradual yet perceptible trend toward integration would prompt a reexamination of the support and need for black organizations and enterprises,” wrote Neil Lanctot.1 A study published in 1947 identified the “dilemma of the Negro business man who as a Negro disapproves of racial segregation but as a business man has a vested interest in segregation because it creates a convenient market for his goods and services.”2

As 1947 dawned, Negro League owners, enjoying steady attendance and presuming that looming integration was “likely to proceed slowly,” did not yet fear the worst.3 They soon suffered two serious blows related to their two biggest stars, neither of whom was Jackie Robinson. In January Josh Gibson died of a stroke at age 35. In the early weeks of the season, fellow superstar Satchel Paige was often absent from the Kansas City Monarchs, opting for an increase in more lucrative exhibition appearances. “The absence of Paige and Gibson during the season’s crucial early months seriously affected the box office appeal of black baseball.”4

But it was Robinson’s debut with the Brooklyn Dodgers on April 15, 1947, that was clearly a watershed moment in the history of baseball – both its all-Black and previously all-White versions – as well as American history as a whole. The dam erected in the name of racial segregation was loudly cracked and poised to burst, releasing a new torrent of Black talent into what were then considered the major leagues.

Robinson and Branch Rickey were the courageous protagonists of the integration story, but neither was poised to champion the cause of the continuation of the Negro Leagues. Robinson had played one season in Kansas City in 1945 and had quickly soured on the experience. He was surprised by the lack of formal contracts, the lack of consistency and professionalism in umpiring and scorekeeping, the poor quality of buses and accommodations, and the drinking and late-night partying of his teammates.5 The disaffection was mostly mutual. “He did not fit in very well,” wrote Donn Rogosin. “He was not a popular player in Kansas City.”6 Robinson later voiced his scathing critiques in a 1948 article for Ebony titled “What’s Wrong with Negro Baseball,” in which he scolded owners “to place more emphasis on the character and morals of the men they select” and less on “worrying so much about heavy schedules and getting in as many games as they can, regardless of the caliber of ball that is played.”7 Back in 1945, before Rickey came calling, Robinson declared his intentions to retire from baseball altogether.8

Rickey was no fan of the Negro Leagues either. He, too, disparaged Negro League owners as unprofessional and lamented their lack of centralized leadership. He gave this as rationale to found his own franchise, the Brooklyn Brown Dodgers, in an upstart all-Black United States League, though this was likely primarily conceived to give cover to his scouts to start watching Black players.9 He then sparred with the Monarchs over the terms of Robinson’s acquisition.10 “There is no Negro league as such, as far as I am concerned,” Rickey said, adding that the Negro Leagues “have no right to expect organized baseball to respect them.”11

Thus the fate of the Negro Leagues was far from Robinson’s and Rickey’s minds in 1947. Nor did it appear to give pause to Black fans, who flocked to Ebbets Field and Dodgers road games at the expense of the teams they used to frequent. “The overall attendance decline in black baseball in 1947 was startling,” Lanctot wrote.”12 Negro Leagues executive Frank Forbes said that while he expected a dip in attendance, “frankly we were not prepared for what we were to experience.”13 The very things that made Robinson’s debut season such a seismic success – his play putting him in contention for Rookie of the Year honors and his team’s trip to the World Series – captivated Black fans and Black sportswriters all season long.14 Unlike Negro League teams, the Dodgers enjoyed prominent coverage in mainstream newspapers and on the radio, keeping them constantly on the minds of Black fans.15

So while integration did proceed slowly when measured by the number of Black players, the intrigue of the effort and the exploits of Robinson had an outsize impact. “With only three of sixteen teams employing a total of five black players in 1947, major league baseball was still far from integrated,” Lanctot wrote. “Yet already many fans had permanently turned away from black baseball, which seemed increasingly less relevant and meaningful when juxtaposed against the enormous appeal of Jackie Robinson excelling in interracial competition.”16

As the 1948 season dawned, the Negro Leagues’ “still decentralized control … limited the likelihood that [they] would assertively address the new challenges with substantial improvement or innovation.”17 Owners appealed to Black fans to return out of loyalty. They cut player salaries to limit their losses. They pursued minor-league affiliations with major-league clubs, but found few takers.18 They sought more revenue from the sale of players to major-league clubs, but lacked leverage to get fair value, and relinquishing their top talent further devalued their product.19

In the midst of a tumultuous offseason, Negro Leagues owners reeled from the added impact of Robinson’s Ebony broadside in early 1948. “Robinson is where he is today because of organized colored baseball,” Newark Eagles owner Effa Manley – now the only woman enshrined in the National Baseball Hall of Fame – blasted back. “[A]n apology is due the race which nurtured him – yes, the team and league which developed him.”20 It was a terrible time to spar with Robinson, who had just soared to stratospheric levels of superstardom.

Robinson’s critique “contained more than a grain of truth,” Lanctot observed. But it showed “little sympathy for the previous decades of struggle to establish the industry and largely failed to acknowledge the impact of inadequate financing and revenue. … Evaluated in this context, black baseball had achieved a great deal despite substantial odds, a fact Robinson chose to ignore.”21

One can now wonder if some combination of forces – centralized leadership among Negro Leagues owners, more favorable representation from Robinson and Rickey, minor-league affiliations and fair player sales from major-league owners, and sustained fan attention – could have saved the Negro Leagues, or if an institution defined by segregation was inherently obsolete once the color barrier was broken. But each of these factors did its damage, and the result was irreversible.

After another season of crushing losses in 1948, the Negro National League was forced to fold. Manley put her Eagles up for sale.22 “[T]he golden era has passed,” Birmingham Black Barons owner Tom Hayes declared. “Teams that are to survive must retrench and proceed with caution.”23 In the ensuing decade, remaining franchises cobbled together rosters, schedules, and crowds – some would even enlist White players – but they were shells of their former selves. “We’d get 300 people in a game,” Buck Leonard lamented. “We couldn’t even draw flies.”24 The Negro American League folded in 1960.25

For decades, the memory of the Negro Leagues faded, before being revived at the end of the twentieth century by researchers and ambassadors. The Negro Leagues’ rightful place in history was finally recognized by Major League Baseball in December 2020 when Commissioner Rob Manfred gave what he called “long overdue recognition” by retroactively conferring major-league status on seven Negro Leagues between 1920 and 1948.

“Negro League players … never looked to Major League Baseball to validate them,” said Negro Leagues Baseball Museum president Bob Kendrick. “But for fans and for historical sake, this is significant. … [I]t does give additional credence to how significant the Negro Leagues were, both on and off the field.”26

NATHAN BIERMA is president of SABR Southern Michigan. He lives in Grand Rapids, Michigan. His writing has appeared in the Chicago Tribune, Chicago Sports Review, and the Detroit Free Press, and in SABR’s recent books on the greatest games at Wrigley Field and Comiskey Park. He is the author of The Eclectic Encyclopedia of English: Language at Its Most Enigmatic, Ephemeral, and Egregious. His website is www.nathanbierma.com.

Notes

1 Neal Lanctot, Negro League Baseball: The Rise and Ruin of a Black Institution (Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Press, 2004), 306.

2 Quoted in Lanctot, 302.

3 Lanctot, 299.

4 Lanctot, 310.

5 Arnold Rampersad, Jackie Robinson: A Biography (New York: Alfred A. Knopf, 1997), 115.

6 Donn Rogosin, Invisible Men: Life in Baseball’s Negro Leagues (New York: Atheneum, 1983), 203. The view that Robinson was not a true ambassador of Black baseball would temper enthusiasm within the Negro Leagues that he was the player chosen to break the color barrier.

7 Lanctot, 332.

8 Rampersad, 124.

9 Rampersad, 123.

10 Rampersad, 130.

11 Rampersad, 131.

12 Lanctot, 317.

13 Lanctot, 317.

14 Lanctot, 316. Robinson won the inaugural award, which at the time spanned both the American and National Leagues, signifying that he not only broke the color barrier, but did so with dominance.

15 Lanctot, 316.

16 Lanctot, 317. Joining Robinson in the majors that year were Larry Doby with the Cleveland Indians, Hank Thompson and Willard Brown with the St. Louis Browns, and Dan Bankhead, also with the Dodgers.

17 Lanctot, 321.

18 Lanctot, 335. Only Alex Pompez, owner of the New York Cuban Stars, was able to secure such an affiliation, with Horace Stoneham and the New York Giants.

19 Lanctot, 336.

20 Lanctot, 334.

21 Lanctot, 333.

22 Lanctot, 338.

23 Lanctot, 342.

24 Rampersad, 132.

25 Leslie Heaphy, The Negro Leagues: 1869-1960 (Jefferson, North Carolina: McFarland & Co., 2003), 224.

26 Anthony Castrovince, “MLB Adds Negro Leagues to Official Records,” MLB.com, December 16, 2020. Accessed at mlb.com/news/negro-leagues-given-major-league-status-for-baseball-records-stats.