Jackie Robinson Calls It Quits

This article was written by Robert P. Nash

This article was published in Jackie Robinson: Perspectives on 42 (2021)

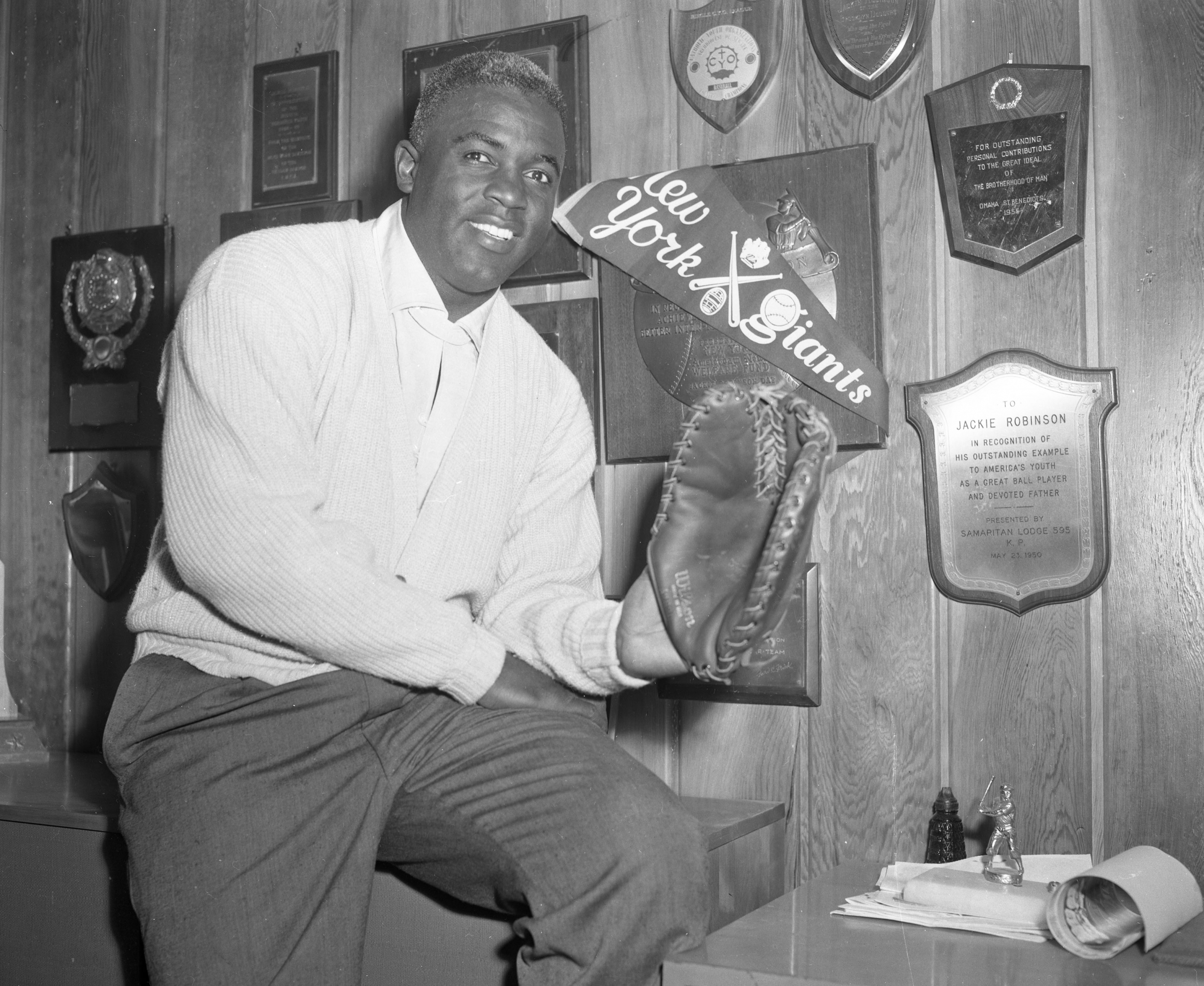

Jackie Robinson lifts a pennant to commemorate his being traded from the Brooklyn Dodgers to the New York Giants on December 14, 1956, at his home in Brooklyn. (SABR-RUCKER ARCHIVE)

In October 1956, the Brooklyn Dodgers faced the New York Yankees in the World Series for the sixth time in Jackie Robinson’s 10 years as a major leaguer. After splitting the first four games, the Dodgers were victims of Don Larsen’s historic perfect game and fell behind three games to two. In Game Six, both teams failed to score through the first nine innings. In the bottom of the 10th inning, Robinson singled to left field to drive in the game’s only run. No one knew it at the time, but that dramatic game-winning hit turned out to be the last hit of Robinson’s storied major-league career.

There would be no such heroics in Game Seven. Robinson did, however, provide the Ebbets Field faithful with one last bit of excitement. With the Dodgers behind 9-0, Robinson came to the plate in the bottom of the ninth inning with two outs and Duke Snider on first base. In his last major-league at-bat, Robinson struck out, but Yankees catcher Yogi Berra was unable to hang onto the third strike. An unrelenting competitor to the very end, Robinson hustled down to first base in a futile attempt to beat Berra’s throw for the final out of the Series.

Robinson and his Dodgers teammates had little time to dwell on their disappointing World Series loss. They left immediately for a monthlong exhibition tour of Japan, where they compiled a 14-4-1 record against tough Japanese competition. Japanese baseball fans got to experience the full range of Robinson’s baseball talents. Midway through the tour, his competitive fires still unquenched, these included the spectacle of a third-inning ejection for too strenuously disputing an umpire’s call.1

Less than a month after the Dodgers returned from Japan, on December 13, 1956, came the stunning news that Jackie Robinson had been traded. Even worse in the eyes of Brooklyn’s supporters, he had been dealt to the Dodgers’ crosstown adversaries, the New York Giants. In exchange for the player who had been such a significant contributor in the most successful decade in franchise history, the Dodgers received a much-traveled left-handed pitcher, Dick Littlefield, and a reported $30,000 in cash. Littlefield was coming off a 4-4 season for the Giants, his seventh team in seven years. One dismayed Dodger fan, undoubtedly echoing the views of many of her fellow fans, said, “I’m shocked to the core. This is like selling the Brooklyn-Battery Tunnel. Jackie Robinson is a synonym for the Dodgers. They can’t do this to us.”2

In his introduction to the 1995 edition of Robinson’s autobiography I Never Had It Made, fellow Hall of Famer Hank Aaron observed: “…after all the things he’d done for the Dodgers, after everything he had suffered, they found it necessary to trade a man of his stature, a man who was the Dodgers. I thought at the time: Stan Musial was never traded; Ted Williams was never traded. We’re talking about someone who was very special, who should have always had a place with the Dodgers. It should have been understood that this man started with the Dodgers and that he would end up with the Dodgers. Certain people you never trade, and Jackie Robinson should never have been traded.”3

Rachel Robinson, Jackie’s widow, confessed years later that when she learned of the trade, “I was angry that the Dodgers would trade him to the enemy Giants. I felt they should have had enough of a sense of history and enough appreciation for what he did to retire him with honors instead of selling him off to the Giants.”4

Although unexpected, rumors involving a Robinson trade had circulated for years. He himself generated such talk as early as his fourth season. Following an August 1950 game in which he had been removed from the lineup after making an error, a frustrated Robinson remarked that it would not surprise him if he were traded: “After all, as ball players go, I’m pretty old at 31 and it wouldn’t be any shock to me.”5 Dodgers President Branch Rickey firmly denied any such plans, but trade rumors continued to crop up for the remainder of Robinson’s career.

During spring training 1955, Robinson expressed his frustration with manager Walter Alston over his playing time and uncertainty about his playing position for the coming season. The previous Dodgers manager, Chuck Dressen, who was then skippering the Washington Senators, created a fuss when he suggested that it looked as though the Dodgers wanted to trade Robinson.6

His ultimate trade to the Giants was even foreseen earlier in the 1956 season when it was suggested that “trade winds are blowing in odd directions. … baseball breezes may blow Jackie Robinson into the Polo Grounds.”7

Robinson had not been consulted beforehand about his trade. While he was undoubtedly disappointed by the news, he was probably not as shocked as baseball fans and members of the news media. He had few illusions, if any, about professional baseball as a business. He would later say, “After you’ve reached your peak, there’s no sentiment in baseball. You start slipping, and pretty soon they’re moving you around like a used car. You have no control over what happens to you.”8

On the same evening that Robinson learned about the deal, he received a phone call from the Giants owner, Horace Stoneham who wanted to get his new acquisition’s thoughts about joining the team. Robinson said he would be happy to play for the Giants, but that he was considering retirement and needed several weeks before giving Stoneham an answer.

For their part, the Giants were very excited about the prospect of having Robinson on their ballclub. Stoneham called him “the greatest competitor I’ve ever seen in baseball.”9 Not only did they value his potential role as a team leader, but even at age 38, they felt, he could still be a key contributor on the field. They hoped he could fill in for their young first baseman, Bill White, who had been called into service with the US Army. Willie Mays, the Giants’ star center fielder, was reportedly thrilled that Robinson would be joining the team, saying it “was the best thing that could have happened to the Giants.”10 Team executives also knew that the Dodgers star and longtime Giants nemesis would be a big box-office draw.

There was much speculation among baseball fans and the press that Robinson would retire rather than accept a trade to the Giants. At a public appearance in December, however, he declared that “as long as I had to be traded, I’m glad it was to the Giants.”11 What no one knew outside of Robinson’s family and a few close associates was that he had already decided to retire before he learned of the trade.

Several years earlier, keenly aware of the inevitable decline of his athletic skills, Robinson had asked his financial adviser and close friend Martin Stone to seek out post-baseball-career opportunities. Those efforts bore fruit when Robinson was approached in early December by William Black, owner of Chock Full o’Nuts, a large chain of New York City coffee shops. Black wanted him for a full-time executive position as vice president for personnel relations. In an untimely confluence of events, Robinson had agreed to a contract with Black only to learn on the very same day that he had been traded to the Giants.

Much of the subsequent controversy surrounding his retirement would have been avoided if Robinson had informed the Dodgers and Giants of his decision to retire at the time of the trade. Two years earlier, however, he had signed a contract with Look magazine giving it the exclusive rights to the story of his retirement. The principled Robinson felt both contractually and morally bound to keep his retirement a secret until the article was published.

The story was to appear in the January 22, 1957, issue of Look, which was scheduled to hit newsstands around the first week of January. Plans called for him to hold a press conference that would coincide with the release of the article. But subscribers received their copies of the magazine a couple of days early, and the news leaked out ahead of time. Much of the baseball establishment and news media reacted negatively, feeling they had been deliberately deceived.

In a brief article titled “Why I’m Quitting Baseball,” Robinson laid out his reasons for retiring, and explained the unusual circumstances surrounding the timing. “There shouldn’t be any mystery about my reasons,” he said. “I’m 38 years old, with a family to support, I’ve got to think of my future and our security. At my age, a man doesn’t have much future in baseball – and very little security. It’s as simple as that.” He went on to say, “I’m through with baseball because I know that, in a matter of time, baseball would have been through with me.”12

Robinson anticipated the potential outcry over his misleading public statements. He wrote, “Some people may now feel I haven’t been honest with them these past few weeks when they’ve asked me about my plans. I’ve always played fair with my newspaper friends, and I think they’ll understand why this one time I couldn’t give them the whole story as soon as I knew it.”13

Despite widespread assumptions to the contrary, Robinson also made it clear that his decision was not due to an unwillingness to play for the rival Giants. He had already decided to retire before he learned of the trade. It was equally evident, however, that he would not have welcomed a trade to any team. “I had just been able to avoid what I dreaded most in baseball,” he commented: “the moment when they would start moving me around.”14

Besides the weeks-long secrecy leading up to his announcement, many were also bothered by the fact that Robinson had sold his story instead of providing it to the newspapers. The selling of a retirement story, however, was not without precedent. Several years earlier, in April 1954, Ted Williams had declared “This Is My Last Year” in a three-part series that appeared in the Saturday Evening Post.15 Williams, who would turn 36 before the end of that season, commented, “I can’t think of a ballplayer I ever saw who looked as if he belonged in a major-league uniform after the age of thirty-six … excepting pitchers, who work only once a week when they’re that old.”16 Of course, not only did Williams not retire after the 1954 season, but he continued to play for six more years before finally ending his Hall of Fame career. Williams’s example held out hope that Robinson might yet reconsider his decision to retire.

If Robinson was seriously entertaining any second thoughts about retiring, however, they were quickly dismissed when Buzzie Bavasi, the Dodgers vice president, suggested in the press that Robinson’s apparent retirement was merely a ploy to get more money out of the Giants. An angry Robinson responded, “There isn’t a chance in the world I’ll ever put on a baseball uniform again,”17 and also that he “wouldn’t play baseball again for a million dollars.”18

Nevertheless, the Giants worked hard to get him to reconsider in hopes that he might consent to play for one more year. Black informed the Giants that he was willing to delay Robinson’s new position for a year. Robinson though, quickly made it clear that his decision to retire was final. On January 14, 1957, in a letter written on a Chock Full o’ Nuts letterhead, Robinson formally announced his retirement. He thanked Horace Stoneham and vice president Chub Feeney, and reiterated that his retirement was not due to his trade to the Giants. “From all I have heard from people who have worked with you,” he wrote, “it would have been a pleasure to have been in your organization.”19

Robinson’s retirement became official after his letter was forwarded to the office of the National League president, Warren Giles. As a result, his December trade to the Giants was rescinded, meaning that he would retire as a member of the Dodgers. His frequent statements that his trade to the Giants was not a factor in his retirement appear to have been sincere. Nevertheless, he said that he was “glad I quit baseball before I was traded, and I bet I’m not the only one. I’m sure the true Brooklyn fans – the ones I really care about – will be tickled to death that they’ll never have to see me playing for another club.”20

The fact that baseball was not the sole priority in Robinson’s life was lost in the commotion surrounding his retirement. On the same day he dramatically broke the major leagues’ color line on April 15, 1947, he told a reporter, “Give me five years of this and that will be enough.”21 Later that same year, after completing his historic first season, he was already hinting about retirement, saying, “I’ve been in sports for a long time and I’m getting a little tired of it.”22

Although Robinson would go on to play for nine more seasons, he frequently spoke about hanging up his uniform. One month after Joe DiMaggio retired at age 36 in December 1951, citing injuries and declining skills, Robinson was asked if he might ultimately retire in the same way. “Well, for one thing,” he responded, “I don’t think I’ll ever last as long as Joe did because those early years in football and other sports (at UCLA and in semipro leagues) took too much out of me. One thing for sure, though, I won’t try to hang on a minute longer than I feel I’m helping the club.”23 In a magazine article published two years before his retirement, he even made the surprising confession that he had never wanted to be a baseball player.24

It is revealing that in Robinson’s autobiography I Never Had It Made, published shortly before his death in 1972 at age 53, the greater part of the book is devoted to his life outside of the game that made him famous. An indication that he had important activities in mind beyond the baseball diamond was demonstrated just five days before his trade to the Giants. On December 8, 1956, he was presented with the Spingarn Medal, awarded annually by the NAACP “for the highest achievement of an American Negro.” The first sports figure to receive the award, Robinson was recognized for his “achievements in business and in public appearances in the interest of race relations.”25 In the following year, the Spingarn Medal was bestowed on Martin Luther King Jr.

It should not be too surprising that Robinson’s departure from baseball ended in such a tumultuous manner. His outspoken manner generated controversy both on and off the field throughout his career. At least some of his troubles were undoubtedly the result of racial bias within the press and baseball’s executive offices. One writer, for example, has contrasted Robinson’s negative treatment with that of Cleveland’s longtime star pitcher Bob Feller, who retired shortly before Robinson.26 Feller was similarly free with his opinions, and not averse to challenging the powers in major-league baseball.

On the other hand, Robinson certainly provided fuel for his critics. Leo Durocher, manager of both the Dodgers and Giants, and himself no stranger to controversy, once commented that “Mr. Rickey might not have been willing to say that Jackie had the ability to make a bad situation worse, but I don’t think he would have said that Jackie ever went out of his way to make it any better either.”27 Robinson himself provided some validation for that opinion: “When I agreed to become the first Negro in Organized Baseball, I also didn’t realize that distinction would get me into so many public arguments and controversies. Ever since I’ve been with the Dodgers, I have been in the middle of all kinds of beefs on the sports pages. Rachel says it’s my own fault. She says I’m too willing to sound off with an opinion when a sportswriter is looking for a story, and she’s probably right. It’s hard for me to say, ‘No comment.’”28

Ultimately, Jackie Robinson delivered this fitting interpretation of the controversial ending to his baseball career: “Some of the writers damned me for having held out on the story. Others felt it was my right. Personally, I felt that Bavasi and some of the writers resented the fact that I had outsmarted baseball before baseball had outsmarted me. The way I figured it, I was even with baseball and baseball with me. The game had done much for me, and I had done much for it.”29

ROBERT NASH, a SABR member since 1992, is a retired special collections librarian and professor emeritus at the University of Nebraska at Omaha. He was a contributor to Kansas City Royals: A Royal Tradition (SABR, 2019) and Rosenblatt Stadium: Essays and Memories of Omaha’s Historic Ballpark, 1948-2012 (McFarland, 2020).

Sources

In addition to the sources cited in the Notes, the author consulted Baseball-Reference.com.

Notes

1 “Dodgers Triumph in Hiroshima,” New York Times, November 2, 1956: 33.

2 “Brooklyn’s Fans Rocked by Trade,” New York Times, December 14, 1956: 46.

3 Hank Aaron, “Introduction,” in Jackie Robinson, I Never Had It Made (Hopewell, New Jersey: Ecco Press, 1995), xvii.

4 Ross Newhan, “Rachel Robinson,” Los Angeles Times, March 31, 1997, latimes.com/archives/la-xpm-1997-03-31-ss-43970-story.html (accessed October 17, 2020).

5 “Rickey Makes a Denial – Dodgers’ Head Says He Has No Idea of Trading Robinson,” New York Times, August 17, 1950: 32.

6 “‘Tsk, Tsk,’ Says Chuck to Smokey Stew,” The Sporting News, April 20, 1955: 24.

7 “Trade of Robinson to Giants Possible,” New York Times, June 7, 1956: 38.

8 Jackie Robinson, “Why I’m Quitting Baseball,” Look, January 22, 1957: 91.

9 Jimmy Burns, “He’s Greatest Competitor of All – Stoneham,” The Sporting News, December 19, 1956: 3.

10 “‘Jackie Will Help Me,’ Says Willie, Signing Giant Contract for 35 Gees,” The Sporting News, January 9, 1957: 8.

11 “Jackie Beams Over Giants at Kids’ Party in Stamford,” The Sporting News, January 2, 1957: 26.

12 “Why I’m Quitting Baseball”: 91.

13 “Why I’m Quitting Baseball”: 91.

14 “Why I’m Quitting Baseball”: 92.

15 Ted Williams, “This Is My Last Year,” Saturday Evening Post, Part One, April 10, 1954: 17-19, 90-94; Part Two, April 17, 1954: 24-25, 147-150; Conclusion, April 24, 1954: 31, 155-158.

16 “This Is My Last Year,” Saturday Evening Post, Part One, April 10, 1954: 17.

17 Dick Young, “Robby Nixes Giants’ Bid to Lure Him Back to ’57,” New York Daily News, January 8, 1957: 47.

18 Gordon S. White Jr., “Robinson, Incensed by Remarks of Bavasi, Is Adamant on Decision to Retire,” New York Times, January 7, 1957: 31.

19 “Robinson Applies for Retirement,” New York Times, January 15, 1957: 47.

20 “Why I’m Quitting Baseball”: 92.

21 Ward Morehouse, “Debut ‘Just Another Game’ to Jackie,” The Sporting News, April 23, 1947: 3.

22 “Jackie Robinson Planning 3 More Years on Diamond,” New York Times, October 26, 1947: S5.

23 John Drebinger, “Robinson Becomes Best Paid Dodger – Signs for Reported $40,000,” New York Times, January 10, 1952: 38.

24 Jackie Robinson, “A Kentucky Colonel Kept Me in Baseball,” Look, February 8, 1955: 90.

25 “Gold Medal Given to Jackie Robinson,” New York Times, December 9, 1956: 50.

26 Ron Briley, “Do Not Go Gently into That Good Night: Race, the Baseball Establishment, and the Retirements of Bob Feller and Jackie Robinson,” in Joseph Dorinson and Joram Warmund, eds., Jackie Robinson: Race, Sports, and the American Dream (Armonk, New York: M.E. Sharpe, 1998), 194.

27 Leo Durocher, Nice Guys Finish Last, (New York: Simon & Schuster, 1975), 212.

28 Jackie Robinson, “Your Temper Can Ruin Us!,” Look, February 22, 1955: 78.

29 Robinson, I Never Had It Made, 122.