Jackie Robinson in 1945: From Boston ‘Tryout’ to a Negro Leagues Star

This article was written by Bob LeMoine

This article was published in Jackie Robinson: Perspectives on 42 (2021)

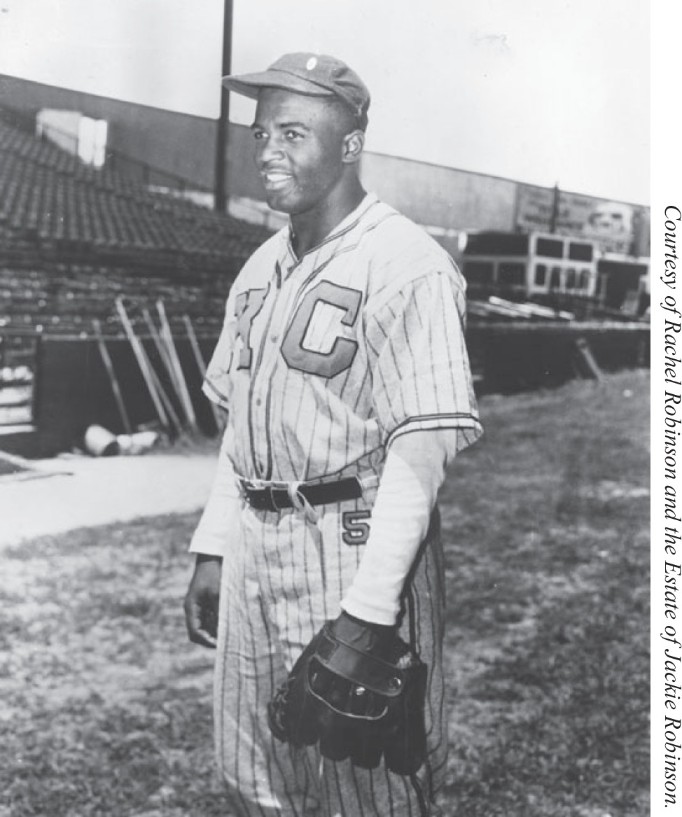

Jackie Robinson with the Kansas City Monarchs, October 23, 1945 (COURTESY OF RACHEL ROBINSON AND THE ESTATE OF JACKIE ROBINSON)

A brief and often forgotten chapter in the legendary life of Jackie Robinson was the five months he spent as the Negro Leagues batting star for the Kansas City Monarchs in 1945. This era is nestled between his discharge from the US Army in late 1944 and his signing with the Brooklyn Dodgers in August of 1945.

With Robinson’s breaking of baseball’s color barrier, inaugurating a new era in the history of sports in America, there followed the perhaps inevitable but also unfortunate demise of the Negro Leagues. An institution since 1920, the Negro Leagues became a shell of their former selves after Robinson and other African-Americans began to receive new opportunities in the major leagues. Robinson bridged the gap between the old and the new, embodying the hopes and dreams African-Americans had since the infancy of the game itself. While major-league baseball talent became more based on skill without the disqualifying element of skin color excluding many, not every player of color would have a new opportunity. However, the landmark event of desegregation, celebrated yearly in the major leagues, may not have happened if not for this brief time when Robinson was propelled to national fame by the Negro Leagues.

“That’s the side of the story that’s not often told,” said Bob Kendrick, president of the Negro Leagues Baseball Museum. “We don’t get Jackie Robinson if not for the Negro Leagues and the Kansas City Monarchs. And that story really has never been expounded on.”1 This article is an attempt to highlight that forgotten story, although for a game-by-game account of that year, see Aaron Stilley’s excellent blog, “Jackie with the Monarchs: Reliving the 1945 Kansas City Monarchs Season.”2 This article will focus on the growing media coverage of Jackie from the ex-UCLA star to a disgruntled player at a Boston “tryout” to a Negro League phenom.

Robinson had been a standout athlete at UCLA in basketball, football, track, and baseball before enlisting in the US Army in 1942. Robinson was “one of thousands of Blacks thrust into the Jim Crow South during World War II,” wrote Jules Tygiel.3 In July of 1944, Robinson was a second lieutenant in the 761st Tank Battalion at Fort Hood, Texas. When he refused to move to the back of the bus (the “colored” area), he was brought before a court-martial. Robinson was exonerated, but the trial itself revealed deep-seated racism, even by those who were representing him. Robinson was honorably discharged in November 1944. “It was a small victory,” Robinson wrote of the trial, “for I had learned that I was in two wars, one against the foreign enemy, the other against prejudice at home.”4

“Had the court-martial of Jackie Robinson been an isolated incident,” wrote Tygiel, “it would be little more than a curious episode in the life of a great athlete. His humiliating confrontations with discrimination, however, were typical of the experience of the Black soldier; and his rebellion against Jim Crow attitudes was just one of the many instances in which Blacks, recruited to fight a war against racism in Europe, began to resist the dictates of segregation in America.”5 That rebellion against segregation was just beginning, however, and Robinson became a chief figure in the growing calls for civil rights. At this point, though, Robinson was “a man still moving largely in the dark,” in the words of Arnold Rampersad, and “was still drifting, drifting, still largely at the mercy of fate and the whims and wishes of whites.”6

He would not drift for long. “While waiting for discharge,” Robinson remembered at Camp Breckinridge in Kentucky, “I ran into a brother named [Ted] Alexander who, before going into uniform, had been a member of the Kansas City Monarchs.”7 The pair struck up a conversation, and Robinson learned that the Monarchs were looking for players. He wrote to the Monarchs and was invited for a tryout at their spring-training facility in Houston, Texas. In the meantime, Robinson used his blazing speed as a running back for the Los Angeles Bulldogs, an independent professional football team, and a short stint coaching basketball at Samuel Huston College8 in Austin, Texas.

The Kansas City Call, a Black newspaper, hailed Robinson as the “prize freshman” on the 1945 Monarchs.9 Robinson made the team and a long season awaited. The Monarchs were known for playing anybody anywhere at any time, even bringing their own portable lighting system with them to take advantage of the evenings. The exhibition season began in Houston on Easter Sunday, April 1, against a group of minor-league all-stars. Robinson went 1-for-7 in his professional baseball debut and “starred afield,” contributing to “three snappy double plays.”10 The game ended in a 4-4 tie after 14 innings. The team traveled to Birmingham, Alabama, on April 8 to take on the Black Barons in a Sunday doubleheader. Robinson went 2-for-4 in the opener and drove in the first two Monarchs runs as they won the first game, 7-0. They were shut out, 2-0, in the nightcap. The Monarchs played Birmingham twice more before both moved on to Atlanta on April 11.11

“Players have to make the jump between cities in uncomfortable buses,” Robinson remembered about the hardships of the Negro Leagues, “and then play in games while half asleep and very tired. When players are able to get a night’s sleep, the hotels are usually of the cheapest kind. The rooms are dingy and dirty, and the rest rooms in such bad condition that the players are unable to use them.”12

The Atlanta Journal Constitution previewed the event with the headline, “Ex-UCLA Gridder to Play Here.” “(The Monarchs) feel that Robinson will plug the open gap they need to win the American League Pennant,” the paper reported.13 There was a special seating section for White fans who wished to attend and all wounded veterans, no matter their skin color, were admitted free.14 The game was played at Ponce De Leon Park, famous for two trees that were in play in center field. Birmingham won, 5-2, and the Monarchs went on to play the Memphis Red Sox in Memphis and then Little Rock, Arkansas.15

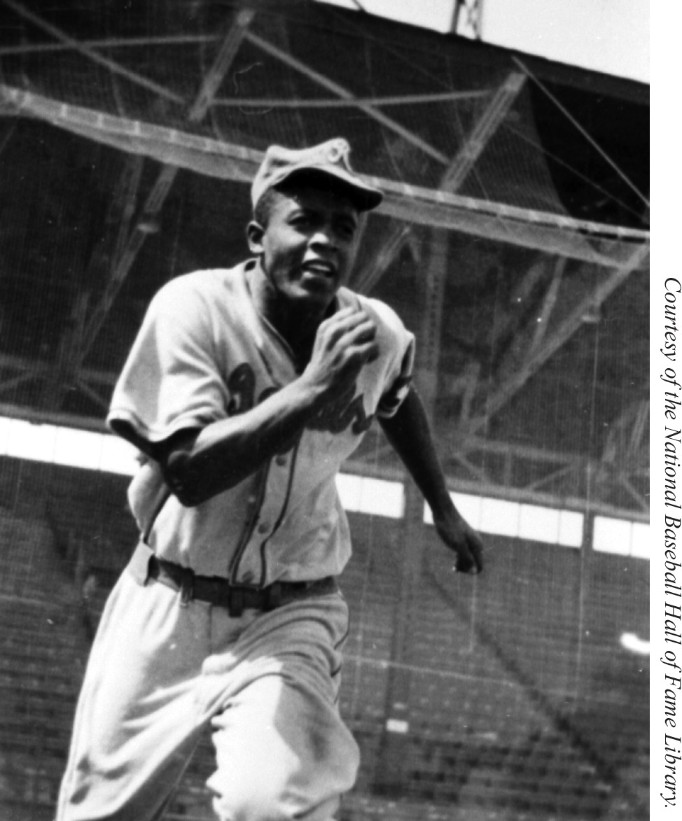

Jackie Robinson in the uniform of the Negro League Kansas City Royals, photographed on October 7, 1945, by Maurice Terrell for LOOK Magazine. (NATIONAL BASEBALL HALL OF FAME LIBRARY)

However, Robinson was not with the team. Instead, he was in Boston for a scheduled “tryout” with the Boston Red Sox at Fenway Park on April 12. Robinson was joined by fellow Negro Leaguers Sam Jethroe and Marvin Williams under the supervision of Red Sox scouts and manager Joe Cronin.16 Wendell Smith, sports editor of the African-American Pittsburgh Courier, was responsible for setting up the tryout, although behind the scenes was Boston City Councilman Isadore H.Y. Muchnick. Muchnick pressured both the Red Sox and the Boston Braves to sign a Black player, threatening to challenge the city ordinance allowing games on Sunday if they did not do so. He had received a promise in writing from both John Quinn and Eddie Collins, general managers of the Braves and Red Sox respectively, confirming that they were receptive to a tryout of Negro League players.

The scheduled tryout on April 12 was canceled, however, for unknown reasons. It seems it would have been the perfect time to hold such a trial, given that the Red Sox and Braves were to play that afternoon at 3 P.M. in their annual spring City Series.17 By late afternoon, news had already spread of the sudden death of President Franklin D. Roosevelt. The Red Sox-Braves games were called off for both Friday and Saturday (April 13-14).18 Some sources have claimed the traumatic event caused the canceling of the tryout, but that doesn’t explain April 12, as Roosevelt died around 4:35 P.M.19 Even with the cancellation on Friday, the Braves and Red Sox still held practice at their own parks as they prepared for the start of the season on April 17.20 As newspaper space was devoted to articles about the late president and the new one, Harry S. Truman, the tryout became something of an afterthought.

The Red Sox and Braves resumed on Sunday, April 15, and 13,000 turned out to see the final exhibition game. Boston Globe writer Melville Webb wrote, “The Negro players did not have their tryout at Fenway yesterday. They will have a session at the Yawkey yard this morning.”21 This was the first mention of the trio in that paper.

The White councilman Muchnick and the Black sportswriter Wendell Smith both sounded off in the Courier about the delays. “They are not fooling me,” Muchnick griped. “Collins and Quinn are giving us the run-around. They promised me that they had no desire to bar Negro players and yet they ‘run out’ every time every time I try to pin them down. These boys came here for a tryout and if they don’t get one it will simply be another mark against the undemocratic practices of major league owners and officials. We are not going to stop fighting, no matter how much they duck and hide and try to evade the facts.”22

Smith set the scenario in historical context and compared himself and Muchnick to the White and Black American Revolutionary heroes Paul Revere and Crispus Attucks. “I am here in the cradle of democracy,” Smith wrote, “here in staid old Boston, where Revere rode and Attucks died, trying to break down some of the barriers and wipe out some of the intolerance they fought to obliterate more than 170 years ago. … We have been here almost a week now, but all our appeals for fair consideration and an opportunity have been in vain. Neither John Quinn of the Braves, nor Eddie Collins of the Red Sox, have displayed so much as a semblance of that indomitable spirit we anticipated here in the shadow of Bunker Hill. … Our fight has not gone unnoticed. We have won compatriots here in Boston who assure us that the ‘Spirit of ’76’ still lives.”23

“We can consider ourselves pioneers,” Robinson told Smith. “Even if they don’t accept us, we are at least doing our part and, if possible, making the way easier for those who follow. Some day some Negro player or players will get a break.”24 Writing later in his autobiography, Robinson said, “Not for one minute did we believe the tryout was sincere.”25

Robinson and others impressed in the tryout, but none of them received a major-league opportunity with the Red Sox. Cronin claimed years later that it was out of fear of sending the players to their minor-league affiliate in Louisville, where they would face harsh treatment. It was better, he thought, to keep separate White and Black leagues. Clif Keane of the Boston Globe was also there that day and over 30 years later claimed he heard someone yell from the stands, “Get those niggers off the field!” Keane believed the culprit was Red Sox owner Tom Yawkey, Collins, or Cronin. Others who were there said they didn’t even hear the slur. If it was said, neither Robinson nor any of the players or Wendell Smith ever mentioned it.

Willie Bea Harmon in the April 27 edition of the African-American Kansas City Call said the tryout was “a little sweat, a train ride at the expense of the Courier and a lot of mumbo-jumbo about how good they looked. That statement might lead one to believe that nothing was gained from the three donning Red Sox suits and working out.” Harmon felt otherwise, however, when the long-term goal was taken into consideration. “Every time a colored player dons a suit in one of the major league camps he breaks down one of the bars that keeps him from playing on major league teams.”26 The Pittsburgh Courier on April 21 allowed space on its front page for both the tryout at Fenway Park and President Roosevelt’s funeral. It hailed Roosevelt as “the best friend the Negro has had in the White House since Abraham Lincoln.”27 There would be no “friends” for them in the Red Sox front office, however.

Robinson’s rise was not going to be in Boston. While the supposed racial slur was probably a fabrication, the Red Sox were the last major-league team to integrate, 12 years after Robinson joined the Dodgers. “No different than the curved streets in its city,” wrote Howard Bryant, “the Red Sox lacked a clear-cut moral direction on race; against this, the combined pioneering spirit of Isadore Muchnick and Jackie Robinson never stood a chance.”28

Robinson’s time had not yet come, and baseball’s unofficial color barrier would continue for a few more months. World War II was over even sooner, and the US Army, which had once brought Robinson to a court-martial over his refusal to move to the back of a bus, began returning its GIs home into a new postwar America.

The next known spring game Robinson appeared in was played on April 22 at Pelican Stadium in New Orleans against the Cincinnati-Indianapolis Clowns. The Monarchs shut down the Clowns, 4-0, as Robinson “clouted an inside-the-park homer in the second inning and rapped out another single as well as showing up well afield and base running,” wrote the New Orleans Times-Picayune. “The former UCLA grid star retired in the seventh inning with an injured finger.”29 The Monarchs continued to play the Clowns for the rest of the month.

“We were fortunate in getting a player of Robinson’s ability,” Monarchs manager Frank Duncan told Oklahoma City’s Daily Oklahoman. “This boy can do everything expecting of an outstanding player. He is a polished, all-around performer and takes a good cut at the ball at the plate.”30 While in Houston, the human side of Robinson and other Monarchs were visible as they visited two area high schools. “The Kansas City Monarch players are always ready to oblige youngsters of today,” the New York Amsterdam News wrote, “and will do everything possible to influence high school boys to play the diamond game. There’s a real spirit in the club this year and it’s mainly due to Jackie Robinson, former grid great at UCLA who is doing a grand job of shortstopping for the Monarchs.”31

The Monarchs concluded their spring training with the Clowns in Houston, Waco, Fort Worth, Dallas, and Oklahoma City. They defeated the Chicago American Giants, 6-2, on the Negro American League’s Opening Day, May 6. Robinson, batting third, knocked in one of those runs with a double. Attendance estimates at Ruppert Stadium (at other times known as Blues Stadium, Muehlebach, and Municipal Stadium) were between 12,000 and 15,000. Probably a bigger story, however, was Robinson’s new “flame,” described by the Pittsburgh Courier: “Jack (The Rabbit) Robinson is carrying a flaming torch for a young lady now attending a California college.”32 No doubt, this was the future Rachel Robinson.

The Monarchs played a Memorial Day doubleheader vs. Chicago on May 30. They rallied for a 4-2 win in the opener, which featured Satchel Paige on the mound. The Monarchs were shut out in the second game, but Robinson had a perfect day at bat in the twin bill. He “doubled, singled and tripled in the second [game]. In the first, he walked three times and on his fourth trip to the plate singled,” wrote the Kansas City Call.33

As June rolled around, Robinson was receiving more attention from the press around the country. He was hailed as the “newest rookie sensation in Negro baseball,” wrote the Evening Star in Washington, where the Monarchs played the Homestead Grays. Robinson “presently is taking his place with colored baseball’s top shortstops and is a spectacular distance hitter.”34 He was batting .326 in early June, according to some accounts, and was labeled a “sensational shortstop.”35

“Right now,” manager Duncan said, “Robinson is just about the best infielder in Negro baseball and should improve with more games under his belt.”36 As the Monarchs came east for a long road trip, mainstream news was naturally highlighting Paige’s arrival, but young Robinson was also mentioned by the New York Amsterdam News. “The colorful Monarchs, rated one of baseball’s great clubs, are bringing besides Paige, the game’s No. 1 attraction, one of the sport’s most valuable additions in years, in the person of Jackie Robinson, stellar shortstop. … On his showing to date with the Monarchs, he appears headed for stardom, and at the rate he is developing, may become one of the all-time great Race shortstops.”37 The Washington Post highlighted Robinson’s talents in a preview of a doubleheader at Griffith Stadium on June 24 against the Homestead Grays: “Robinson is not only shaping up as a consistent hitter with tremendous power, but also is fitting neatly into the shortfield despite his big game. The big fellow is amazingly agile, is a smooth and graceful defensive man and has one of the best throwing arms in baseball.”38 Robinson doubled and scored in the first inning to give the Monarchs an early lead in the opener and finished the contest 4-for-4. However, Paige was rocked by the Grays and the game turned into a laugher, 11-3. The Grays kept up their hitting in the second game, winning 10-6, but Robinson finished 7-for-7 in the twin bill, reportedly tying a record by Showboat Thomas in 1943. Monarchs third baseman Herb Souell went 7-for-9 and the duo accounted for 14 of the team’s 21 hits. Perhaps even more impressive was the crowd of 18,000 or more who turned out in their Sunday best.39

The summer was heating up but the first half of the season was cooling down. The upstart Cleveland Buckeyes and their star hitter Sam Jethroe, who was with Robinson at the Boston tryout, clinched the league’s first-half championship. They were in Kansas City for doubleheaders on July 1 and 4, after which the first half concluded. The Monarchs lost both sets of doubleheaders.40 Robinson launched two home runs in Muskogee, Oklahoma, on July 7 to beat Birmingham.41

Wendell Smith of the Courier compared the best shortstops in the Negro American League: Jud Wilson of Birmingham, batting .359 with two home runs; Avelino Cañizares, the “Cuban Wonder,” of Cleveland (.344, 3); and Robinson (.350, 2). “So, there you are,” Smith concluded, “three young shortstops in Negro baseball who certainly should be given a chance to play in the major leagues.”42 Bill Burk of the Chester (Pennsylvania) Times wrote that the Monarchs with Robinson had “a drawing card that someday may compare to that of the immortal Satchel. The sensational infielder of the Monarchs is a colored boy. If he were white the Lloyd Park (of the local Lloyd A.C. team) would be filled two hours before game time with major league scouts, managers, and owners, all trying to sign him up to a contract. As it is he is rapidly assuming his spot among the greats of his own race – Paige, Josh Gibson, Buck Leonard.”43

The Monarchs were in Detroit on July 22 to take on Memphis in a doubleheader. The first game was scoreless until the sixth, when Robinson knocked in a run with a perfect squeeze bunt. He then stole second and third and scored on a dropped throw to the plate. Over 25,000 fans packed Briggs Stadium to see the Monarchs sweep the doubleheader.44

The annual East-West Game, filled with all-star talent of the Negro Leagues, was held in Chicago on July 29. Robinson batted second for the West behind teammate Jesse Williams and went 0-for-5 in a forgettable performance. The West won, 9-6, and Robinson ended the game with a slick defensive play on a grounder.45

In early August the Monarchs went on a road trip to Philadelphia, Pittsburgh, Washington, Boston, and New York City. In New York, 19,000 came out to Yankee Stadium to see Paige strike out eight and beat the Black Yankees, 4-1. Robinson went 2-for-3 in the dominating outing by Paige.46 The Monarchs brought their portable lights to Boston for a game against a naval team on August 13. The much-hyped Paige failed to show due to car issues, but William “Sheep” Johnson of the African-American Boston Chronicle noted the fine work of Robinson in the 11-1 win, even emphasizing in caps the failure of the Red Sox not to have signed the phenom.47

Jackie gave the fans thrill after thrill by his brilliant fielding, base running and hitting. His drag bunt, his delayed steal of third, and his stealing home with the opposing pitcher, looking right down his throat, unable to do anything about it, were his three sensational plays. Jackie proved why he is the talk of the country. He acts like a Big Leaguer, hits like a big leaguer, thinks like a big leaguer, throws like a big leaguer, and he fields like a big leaguer at shortstop. In fact HE IS A BIG LEAGUER AND AS THE COLONEL FROM THE BOSTON RECORD (Dave Egan) SAYS ‘THE RED SOX COULD USE HIM RIGHT NOW AND PERHAPS GIVE THE BOSTON FANS A REAL BIG LEAGUE CLUB.48

Not that the game would have received a lot of press coverage anyway, but people were closely following news reports on the imminent surrender of Japan and the end of World War II. The Boston Globe’s headline in the evening edition on August 14 finalized it: “JAPS SURRENDER.” The Monarchs stayed a few more days on the East Coast before settling for a tie in a game in Washington on August 16 before rushing to catch a train for Ohio.49 The Monarchs had games against the Clowns in Indianapolis, Cincinnati, and Memphis. Robinson injured his shoulder and saw only limited action, or maybe none at all. The team then traveled to Chicago for a series August 24-27 against the Giants. The Monarchs were swept in the four-game series, but that matters little from the perspective of history. The baseball world was forever changed on August 24, 1945.

Clyde Sukeforth was a baseball lifer, having caught for Brooklyn in the 1920s and ’30s, then managing in the minor leagues before being promoted in 1943 to the Dodgers major-league coaching staff. In 1945 his main job was finding players for the Brooklyn Brown Dodgers team in the new United States League that Dodgers President Branch Rickey was establishing for Black players. Jules Tygiel wrote, “The Dodger president’s true design for this new entity remains unclear. Its primary function was to allow the Dodgers to search for Black players, but Rickey also attempted to create a viable league that would compete with the Negro National and American circuits. Through the United States League, Ricky played both ends against the middle, attempting to gain a slice of the profits from Jim Crow baseball, while simultaneously spearheading the cause of integration.”50

Sukeforth met Robinson at Comiskey Park on August 24, informing him of Rickey’s interest. This led to the duo traveling to Brooklyn to meet Rickey in his office. At that momentous session the color barrier of the national pastime was forever ripped apart. Robinson returned briefly to the Monarchs, being asked by Rickey to remain silent of their historic agreement until November. “I went to the management of the Kansas City club to get permission to play up until September 21 in exhibition games and then go home, as I was tired,” Robinson remembered. “I was told I would have to play all the games or none. I was left with no other alternative than to leave the ball club.”51 Robinson would spend 1946 with the Dodgers’ Triple-A affiliate in Montreal before making his way to the major leagues with Brooklyn.

Negro League statistics are often problematic. Seamheads lists Robinson batting .384 with the Monarchs, while Baseball-Reference credits him at .414. The Center for Negro League Baseball Research records him batting .345 in 41 games. Nevertheless, no matter what the actual statistics were, we see a picture of the rising star who would one day change the game forever. The Monarchs finished a disappointing third in the standings, but Jackie Robinson’s road to transforming the game went through Kansas City.

BOB LeMOINE is a librarian and adjunct professor in New Hampshire. A lifelong Red Sox fan, Bob has contributed to several SABR projects and was co-editor of two SABR books: Boston’s First Nine: the 1871-75 Boston Red Stockings, and The Glorious Beaneaters of the 1890s.

Sources

In addition to the sources listed in the Notes, the author depended on contributions from the following persons and sources:

Bill Nowlin

Stout, Glenn. “Tryout and Fallout: Race, Jackie Robinson, and the Red Sox,” Massachusetts Historical Review Vol 6 (2004): 11-37.

Notes

1 Gregorian Vahe, “Before Changing History, Jackie Robinson’s Path Was Paved by Time with KC Monarchs,” Kansas City Star, January 31, 2019.

2 The blog can be found at jwtm1945.blogspot.com.

3 Jules Tygiel, “The Court-Martial of Jackie Robinson,” American Heritage 35, No. 5 (1984). Retrieved November 2, 2019. americanheritage.com/court-martial-jackie-robinson.

4 Jackie Robinson, Baseball Has Done It (Brooklyn, New York: lg Pub, 2005), 49.

5 Tygiel.

6 Arnold Rampersad, Jackie Robinson: A Biography, (New York: Ballantine Books, 1997), 112.

7 Jackie Robinson, I Never Had it Made (New York: Harper Collins, 1995), 23; Other sources list Hilton Smith, not Alexander, as the person Robinson met, suggesting that Robinson’s memory of the meeting was incorrect.

8 Samuel Huston College, now known as Huston-Tillotson University, is a historically back private institution, not to be confused with Texas’s Sam Houston State University.

9 “Monarchs Ready for Training,” Kansas City Call, March 16, 1945.

10 “Kansas City Battles All-Stars to Tie in 14-Inning Tilt,” Pittsburgh Courier, April 7, 1945: 12.

11 “Birmingham, Monarchs, Split Two Sunday Tilts,” Pittsburgh Courier, April 14, 1945: 12.

12 Jackie Robinson, “What’s Wrong with Negro Baseball?” Ebony 3 No 8 (1948): 17.

13 Atlanta Journal Constitution, April 10, 1945: 12.

14 “Black Barons Play Monarchs,” Atlanta Journal Constitution, April 11, 1945: 9.

15 Aaron Stilley, “A Loss to the Black Barons in Atlanta,” an entry in his blog “Jackie with the Monarchs: Reliving the 1945 Kansas City Monarchs Season.” Retrieved November 3, 2019. jwtm1945.blogspot.com/2010/04/loss-to-Black-barons-in-atlanta.html.

16 Though the Red Sox had also failed to sign Jethroe at the tryout, he later became National League Rookie of the Year for the Boston Braves in 1950. See Bill Nowlin, “Sam Jethroe,” SABR BioProject, sabr.org/bioproj/person/5f1c7cf9.

17 Boston Globe, April 12, 1945: 19.

18 “School Sports, Baseball, Road Race Are Off,” Boston Globe, April 13, 1945: 7.

19 “Suffers Fatal Stroke at Palm Springs,” Boston Globe, April 13, 1945: 1.

20 Melville Webb, “Boston Ball Clubs Call Off Two Games,” Boston Globe, April 14, 1945: 4.

21 Melville Webb, “13,000 See Red Sox Top Braves in Charity Game,” Boston Globe, April 16, 1945: 13.

22 Wendell Smith, “Quinn and Collins ‘Hide’; Councilman Continues Fight,” Pittsburgh Courier, April 21, 1945: 12.

23 Wendell Smith, “‘Smitty’s’ Sports Spurts,” Pittsburgh Courier, April 21, 1945: 12.

24 Smith, “Quinn and Collins ‘Hide.’” 25 Robinson, I Never Had It Made, 29.

26 The article is quoted by Aaron Stilley in his April 16, 2010, blog entry “Tryout with the Red Sox.” Retrieved December 1, 2019. jwtm1945.blogspot.com/2010/04/tryout-with-boston-red-sox.html.

27 “Roosevelt Mourned as Best Friend of Race Since Lincoln and Willkie,” Pittsburgh Courier, April 21, 1945: 1.

28 Howard Bryant, Shut Out: A Story of Race and Baseball in Boston (Boston: Beacon Press, 2002), 40.

29 “Monarchs Defeat Clowns in Negro Baseball, 4-0,” New Orleans Times-Picayune, April 23, 1945: 12.

30 “Monarchs Bring UCLA Ace Here,” Daily Oklahoman (Oklahoma City), May 1, 1945: 12.

31 The article is quoted by Aaron Stilley in his April 29, 2010, blog entry, “Exhibition Tour with Clowns Continues with Win in Houston.” Retrieved December 4, 2019. jwtm1945.blogspot.com/2010/04/exhibition-tour-with-clowns-continues.html.

32 “Negro League President to Pitch First Ball Tuesday,” Journal Times (Racine, Wisconsin), May 28, 1945: 12; Wendell Smith, “The Sports Beat,” Pittsburgh Courier, May 19, 1945: 12.

33 Cited in Stilley’s blog entry on May 30, 2010, “Satchel Makes First ’45 Appearance & Jackie Is Perfect at the Plate.”

34 “Newest Negro Diamond Star Makes D.C. Debut,” Washington Evening Star, June 20, 1945: 17.

35 Hitting vs. Pitching at Dell Thursday, The Tennessean (Nashville), June 6, 1945: 11.

36 “Monarchs Boast New Star in Jackie Robinson,” Rochester Democrat and Chronicle, June 12, 1945: 18.

37 New York Amsterdam News, June 16, 1945. Cited in Stilley’s blog entry June 17, 2010, “Monarchs Invade Yankee Stadium, Take On Philly Stars.” Jwtm1945.blogspot.com/2010/06/monarchs-invade-yankee-stadium-take-on.html.

38 “Monarchs Feature Paige, Robinson in Double-Header,” Washington Post, June 23, 1945: 8.

39 “18,000 Watch Grays Blast Satchel Paige,” Washington Post, June 25, 1945: 9; “Grays Beat Kansas City in Twin Bill,” Pittsburgh Courier, June 30, 1945: 12. The Courier said the crowd was over 20,000 and that game one was a 12-3 final.

40 “Monarchs in 4 Losses,” Kansas City Call, July 6, 1945. Cited in Stilley’s blog entry July 4, 2010, “First Half Ends With Two More Losses to Buckeyes.” jwtm1945.blogspot.com/2010/07/first-half-ends-with-two-more-losses-to.html.

41 “Monarchs Win Saturday Tilt,” Kansas City Call, July 13, 1945.

42 Wendell Smith, “The Sports Beat,” Pittsburgh Courier, July 14, 1945: 12.

43 Bill Burk, “Sports Shorts,” Delaware County Times (Chester, Pennsylvania), July 14, 1945: 9.

44 “Kansas City Wins Two Games in Detroit Before 25,286 Fans,” Pittsburgh Courier, July 28, 1945: 12.

45 Edward Prell, “West’s Negro All-Stars Win 3d in Row, 9-6,” Chicago Tribune, July 30, 1945: 17.

46 Haskell Cohen, “Satchel Sparkles as Kansas City Triumphs,” Pittsburgh Courier, August 18, 1945: 12.

47 “Monarchs Win, 11-1, Without ‘Satchel’ Paige,” Boston Globe, August 14, 1945: 4.

48 William “Sheep” Johnson, “Sports Shots,” Boston Chronicle, August 25, 1945. Cited in Stilley blog entry “Monarchs Triumph in First Ever Night Game at Braves Field,” August 13, 2010. jwtm1945.blogspot.com/2010/08/monarchs-triumph-in-first-ever-night.html.

49 “Memphis and Monarchs Win in Capitol,” Pittsburgh Courier, August 25, 1945: 12.

50 Jules Tygiel, Baseball’s Great Experiment: Jackie Robinson and His Legacy (New York: Oxford University Press, 1997), 57.

51 Robinson, “What’s Wrong with Negro Baseball?” 22.