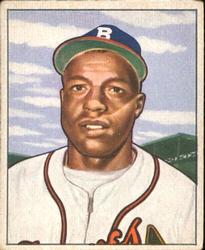

Sam Jethroe

Sam Jethroe was the National League Rookie of the Year in 1950, playing for the Boston Braves, and the first African American to play major-league baseball in Boston. Five years earlier, he’d tried out for the Boston Red Sox at Fenway Park, along with Jackie Robinson and Marvin Williams, but the Red Sox pursued none of them. Robinson went on to break the major-league color barrier and won Rookie of the Year in 1947.

Sam Jethroe was the National League Rookie of the Year in 1950, playing for the Boston Braves, and the first African American to play major-league baseball in Boston. Five years earlier, he’d tried out for the Boston Red Sox at Fenway Park, along with Jackie Robinson and Marvin Williams, but the Red Sox pursued none of them. Robinson went on to break the major-league color barrier and won Rookie of the Year in 1947.

Near the end of his life, Jethroe struggled financially because he was denied a major-league pension for lack of sufficient service time.

At 6-feet-1 and 178 pounds in his prime, the switch-hitting Jethroe (who threw right-handed) was known as the “Jet” – and many considered him the fastest man in baseball in his day. He was a better than average batter, although not nearly as accomplished on defense.

After his playing career ended, when asked which year was his first in professional baseball, Jethroe told the Hall of Fame it was 1948. That was the year he first played in the minor leagues – in the outfield for the Montreal Royals, the Brooklyn Dodgers’ top farm team. He played in 76 games and hit for a .322 average, with just one homer and 25 RBIs. He wasn’t as much for driving in runs, but he got on base a lot and scored 52 runs. In Montreal again in 1949, he played a full 153 games and hit for a .326 average, with 83 RBIs and a league-leading 154 runs scored. He set a league record with 89 stolen bases. His 207 base hits and 19 triples also led the International League, and he was one of the three outfielders named to the league all-star team. Under manager Clay Hopper, Montreal won league flags in 1946, with Jackie Robinson, and in 1948 with Jethroe.

Jethroe’s speed on the base paths earned him the sobriquet “Jet Propelled Jethroe,” later shortened to “The Jet.” He was also dubbed “Larceny Legs” and “Mercury Man” and “The Colored Comet.”1

Jethroe was ready for the major leagues. And for Branch Rickey, this was a chance to cash in on his outfielder’s talent.

But 1948 was not truly Jethroe’s first year of professional baseball. That came a full decade earlier, when Jethroe played for the Indianapolis Clowns in the Negro American League. The Boston Chronicle reported he hadn’t played baseball at Lincoln High School but had been a star at softball.2 As was not uncommon in those days, he did not graduate from high school until he was 23, in 1940. While still in high school, he played for the Indianapolis Clowns in the Negro American League, in 1938; in 1940 and 1941 he played semipro ball, declining several offers from “Negro professional teams” in order to care for his mother, who was quite ill. She died on New Year’s Eve in 1941.3 Jethroe returned to pro ball in earnest in 1942 to play for the Cleveland Buckeyes, for whom he played into early 1948.4 It was a Buckeyes uniform Jethroe wore when he took part in the 1945 tryout at Fenway Park.

Negro Leagues statistics aren’t as complete as we would like; but that Jethroe was brought back year after year speaks to good performance, and that he was signed to Montreal and fared well there also testifies to his talents as a ballplayer. Four times he was selected to the Negro Leagues’ East-West All-Star Game, playing in seven games—two games apiece in 1942, 1946, 1947, and one in 1944.

Samuel Jethroe came from a farming family in Old Zion, Lowndes County, Mississippi. His parents moved to East St. Louis, Illinois at some point, perhaps very shortly after Samuel was born. His parents were Albert “Chip” Jethroe, who at the time of the 1930 census had his own farm at East St. Louis, and Janie Jethroe, who worked as a sheller in a nut factory. She also worked some as a domestic, according to news stories contemporary to Sam’s career. Sam had a sister, Rachel, who was about a year older, and a brother, Jessie, about four years younger. According to census records, Janie had been born Mary Jannie Spruil. Sam’s notarized birth certificate said his mother’s name was Jannie Adams.5

We believe that Sam was born on January 23, 1917 in Lowndes County, though both he himself and the Social Security Death Index gave his birthplace as East St. Louis. He gave his year of birth as 1922, and a number of contemporary accounts indicate years ranging from 1918 to 1922; however, his reported age at the time of the 1930 census was 13 years old. We assume that those later years reflected a fictional “baseball age”; they were there to make him appear younger and thus to offer longer future potential for a team that might sign him. “I was born in 1917,” he later confirmed to Rich Marazzi.6 When he came to the big leagues, it was with the Boston Braves in 1950. Fortunately, age wasn’t an issue to his manager, Billy Southworth. “I don’t care if he’s 50, just as long as he can do the job.”7

Jethroe played semipro ball while growing up, playing for both the East St. Louis Colts and St. Louis Giants. He would hitchhike to Sportsman’s Park in St. Louis and peek through a knothole to watch Dizzy Dean and the Cardinals.8 And he grew up almost next door to Hank Bauer. “His backyard touched my backyard, and we’d play games, Hank Bauer’s team and my team,” Sam said.9 Of course, Bauer’s team was all White and he went on to the major leagues, while Jethroe “would play doubleheaders for the East St. Louis Colts, then head over to St. Louis for a night game…those teams were all black…and I made hardly nothing.”

Marazzi writes that Jethroe, while with the Buckeyes in 1942, led the Negro American League in numerous categories – batting average, base hits, runs scored, doubles, triples, and stolen bases.10 In 1944, his .353 average led the league.

It was in early 1945 that Jethroe took part in the tryout at Fenway Park. The pressure was growing on what was then known as “Organized Baseball” to desegregate, particularly because soldiers who had come back from putting their lives on the line for the country during World War II found a color bar still preventing them from playing professional baseball other than in the Negro leagues.11 Boston City Councilor Isadore Muchnick threatened to pull the special permit that the City of Boston accorded the Red Sox which enabled them to play baseball on one of the most lucrative days of the week – Sundays. The Sox wanted to hold onto Sunday baseball and so agreed to hold a tryout for a select three Negro Leaguers brought to Boston by Pittsburgh Courier sportswriter Wendell Smith. Jethroe, Marvin Williams, and Jackie Robinson suited up at Fenway on April 16, 1945 and worked out for coach Hugh Duffy.12 Red Sox manager Joe Cronin was present as well. Robinson later said of Jethroe, “He looked like a gazelle in the outfield.”13

Duffy said he was impressed, but none of the three ever heard from the Red Sox again. Rather than becoming the first major-league team to integrate, the Red Sox ending up being the last – in 1959. Jethroe recalled that the Red Sox “said we had all the potential but it wasn’t the right time.”14 Cronin later said he told the players that since Boston’s top farm club was in Louisville, “we didn’t think they’d be interested in going there because of the racial feelings at the time.” But he also admitted, “We all thought because of the times, it was good to have separate leagues.”15

Jackie Robinson was indeed bitter about the incident, at least when he spoke about it later. But as for Jethroe the Boston Globe’s Larry Whiteside wrote, “Unlike Robinson, he took life as it came.” Though they’d been told that the time wasn’t right (Muchnick said he never heard that explanation), Jethroe allowed, “The Sox were nice. I mean they didn’t take us to dinner or anything, but they were all right. It was just a workout.”16 He hadn’t gotten too upset, he said, because the three figured nothing was going to come of it anyway.17 As to the idea they might have actually been signed and brought into Organized Baseball, “I don’t think it ever dawned on any of us.”18 He also told Herald reporter Gerry Callahan that he’d heard no racial slurs on the field that day.

Jethroe may have been a bit more candid shortly afterward with some of his Buckeyes teammates. Willie Grace says that Jethroe told him “…‘What a joke that so-called tryout was.’ He said you just knew it was a farce” and that Cronin, although he was there, was “up in the stands with his back turned most of the time.”19

Tryout over, Jethroe reported to Cleveland, put his Buckeyes uniform back on and once more led the league, this time with a .393 batting average. The Buckeyes also won the Negro World Series that year, sweeping the Homestead Grays.

Was Jethroe disappointed, or angry, that the Red Sox had turned him away? “No, I never thought about it,” he told Marazzi. “When I played in the Negro Leagues, I enjoyed it. I loved to play ball and baseball was fun then. I played against Don Newcombe, Monte Irvin, Henry Thompson, ‘Double Duty’ Radcliffe, Gentry Jessup, and many others.”20

After the 1946 season, Jethroe joined the Satchel Paige All-Stars and barnstormed through 17 games, playing against a team of major leaguers headed by the entrepreneurial Bob Feller. Paige’s team won seven of them. Jethroe gave Feller credit for helping Black players into the majors. “He gave us a chance to show what we could do against major leaguers.”21

Jethroe was courted by Mexican League head honcho Jorge Pasquel to play ball in the Mexican League but declined. He did go to Venezuela for a while and was there when the news broke that Jackie Robinson had been signed. Jethroe played in the Cuban Winter League in 1947-48 and again in 1948-49. Playing center field for Almendares, Jethroe hit a team-leading .308 and led the league with 53 runs scored and 22 stolen bases.22 He again led the league in stolen bases (with 32) for the 1948-49 Almendares team, though his 37 strikeouts also led the league. He hit .320 in that year’s Caribbean Series.23

In his quest for a better Brooklyn team and to desegregate the majors, Dodgers GM Branch Rickey reportedly interviewed Jethroe as well as Robinson. But Jethroe acknowledged that he smoked and drank, and Rickey felt he needed to go with a more clean-cut pioneer. He selected Robinson. “He had everything Mr. Rickey wanted,” Jethroe said, “He was a college man who had experienced the white world, and I wasn’t.”24

But Fresco Thompson scouted Jethroe and the Dodgers did purchase Jethroe’s contract from the Buckeyes for a reported $5,000, and in July 1948 assigned him to Montreal.25 He had the two exceptional years noted above, and there were those who called him “the man who made Montreal forget about Jackie Robinson.”26 For instance, in the first 11 games he played against the Buffalo Bisons, Jethroe put together a different sort of streak – he stole at least one base in each game.27 Buffalo manager Paul Richards, Bob Dolgan wrote, “was so fearful of leadoff man Jethroe’s speed, he would intentionally walk the pitcher in front of him, blocking Jethroe’s running.”28 When they did pitch to Jethroe in the Negro Leagues, Buck O’Neil recalled, “the infield would have to come in a few steps or you’d never throw him out.”29

During spring training in 1949, Jethroe was clocked in a 60-yard sprint at 5.9 seconds—two -tenths of a second faster than the world’s record at the time. Stunned as to what his stopwatch showed, the Dodgers’ Arthur Mann later helped arrange an exhibition 75-yard dash against Olympian Bunny Ewell. Jethroe beat Ewell by a few yards.30 Another race that spring clocked Jethroe at 6.1 seconds, tying the world record.31 He could run fast in games, too, of course. Arthur Daley of the New York Times noted the time Jethroe had scored from second – standing up – on an infield dribbler.

Rickey had Duke Snider in center field and really had no place in the big leagues for Jethroe. He may also have decided that Jethroe lacked power in his bat; Jethroe had hit just the one home run for the Royals. During a phone call with Boston Braves GM John Quinn on September 30, Rickey sold Jethroe’s contract to the Braves.32 It was a big deal, said to have been for at least $100,000. New York sportswriter Dan Daniel said the Jethroe sale – one of several Rickey made in a flurry that netted the Dodgers well over half a million dollars – brought Brooklyn $125,000 and Clint Conatser and Don Thompson.33 The caption for the AP wirephoto that ran in the October 12, 1949 Boston Herald said Jethroe was “regarded as the greatest base runner since Ty Cobb was in his prime.”

It was a big deal in other ways, of course, and it’s interesting that more than 10 years earlier, John Quinn’s father Bob Quinn, Sr. had talked with Boston journalist Doc Kountze and envisioned the end of segregation in baseball. Quinn felt it only right that the color line should be breached in Boston, which had fashioned itself the “Cradle of Liberty” at the time of the American Revolution. Quinn knew that major-league owners would have voted him down in 1938, but he did predict the change would happen with the National League Braves (they were the Boston Bees in 1938) before it would happen with the Red Sox.34

Jethroe wasn’t the only Black player in the Braves organization. Announcing the acquisition, the Boston Herald wrote, “He is the first Negro signed to a Braves contract, though there are several Negroes in the organization.”35 There was a rumor a few days later that the Braves had also purchased Jackie Robinson.36 That was quickly denied, but it was clear that Jethroe, more than the also-acquired Bob Addis, had been the Braves’ target in their dealings.37

There was some early thought that Rickey had discarded Jethroe; New York writer Joe Williams had dubbed him a “gold-brick…who doesn’t seem to be able to throw at all.”38 But Rickey himself said, “It might be the biggest mistake I ever made in baseball.”39

In any case, come 1950 Sam Jethroe, the first Black ballplayer for the Boston Braves, was indeed a 33-year-old rookie in the major leagues. But he had a resume in professional baseball dating back into the 1930s.

Jethroe felt welcome immediately, although things did not always go smoothly as the season wore on. First, though, there was spring training. The Braves trained in Bradenton, Florida, and while perhaps Bostonians would welcome him – a proposition yet to be tested – this was less likely to be the case in those days in Florida.

A year earlier, Jethroe had trained with the Dodgers at Vero Beach in 1949. Though there were communities that were resistant to “race-mixing” in baseball, the Dodgers had been pleased with Robinson’s reception and his being named Rookie of the Year in 1947. The 1948 Dodgers had welcomed future Hall of Famer Roy Campanella, and the Cleveland Indians added Larry Doby, who helped them win the 1948 World Series. In January 1949, several Southern cities that had previously barred Black and White ballplayers from playing in the same games actually reached out with invitations to the Dodgers to come and play in their locales during spring training. They included Miami and West Palm Beach in Florida, Atlanta and Macon in Georgia, Greenville in South Carolina, and Houston and San Antonio in Texas. The Dodgers trained at Vero Beach, although at the Naval Training base that was outside the city limits.

Jethroe played against the Cardinals (March 13) and Yankees (March 21) at St. Petersburg – the first time the color bar had been dropped there — and “caused no stir whatever…produced no reaction except insofar as a small mention in the local Independent.”40 The St. Petersburg Times did not even mention that Jethroe was a “Negro.” About 300 Negroes were among the 3,157 who came out to the Cardinals game.

There actually had been an incident, but a very quiet one the newspaper apparently had not heard about. Jethroe remembered it years later: “John Quinn met me at the airport and asked me questions about what things might bother me and he told the players about how I felt. One time, at a restaurant in Florida that spring, they refused to serve me and the team said, ‘Sam, if they don’t serve you, they won’t serve us.’ I told them to go on in, that I wasn’t hungry.”41

Right from the start, questions were raised about Jethroe’s defense. Under the headline “$100,000 Jethroe May Be Flop in Outfield,” Bob Ajemian wrote in The Sporting News that while there was no doubt whatsoever about his being faster than anyone in the majors, and that he ought to be able to hit major-league pitching from either side of the plate, he “cannot throw with a major league arm” and “cannot field well enough to hold down a vital center field post satisfactorily.”42 He didn’t seem to get a good jump on the ball and counted on his speed to enable him to play more deeply than might otherwise be wise; he saw a few balls drop in front of him that a better center fielder may have caught.

Harold Kaese of the Boston Globe agreed. He wrote that “he cannot throw or judge a fly well enough to play center field…This Jethroe looks so fast and his arm looks so weak that it’s even money he can carry the ball in from center field as fast as he can throw it in.”43

The Braves brass was worried. Jethroe himself was a little discouraged and said, “Don’t know but what I ought to pack up and go home, if they really have quit on me.”44 Bob Holbrook wrote after the 1950 season was over that Jethroe had put together “one of the finest comeback epics in recent years.” How could player mount a comeback when he’d never played in the majors before? That’s because, Holbrook said, Jethroe had been “washed up before he played a game. Writers took one look at him and gasped. He couldn’t throw, he couldn’t hit and he couldn’t field. Fly balls dropped around him so profusely that people were afraid he’d get hit on the head.”45 Jethroe himself had let one ball drop during a night game, and reportedly joshed, “I lost it in the moon.”46

He “isn’t living up to his pre-training camp raves,” wrote Frank Santos of the Boston Chronicle, an African-American newspaper, “finding it rather hard to adjust himself to the so-called big league.” But Santos added that Jethroe had recently begun to find himself. Manager Billy Southworth stuck with Jethroe, counseling patience. And Santos seemed to have little doubt that Jethroe would get a good reception in Boston, writing, “One thing is certain, that the hometown fans of the Boston Braves will be rooting for him.”47

Santos was right; Jethroe was quite a hit with fans from the start. Once they saw him run, they were even more convinced. Holbrook wrote, “Jethroe’s box-office appeal amazed even the Braves’ front office who knew they had acquired a good outfielder but never guessed the staid Boston fans would adopt him as their favorite National League player and murmur with excitement every time he reached base.”48

Staid, but also racist? Jethroe was eager to play in Boston, “but I was also anxious because I knew when I arrived there, more was required for me to do than a white player,” Jethroe told Larry Whiteside.49 He hadn’t been able to board with the team in St. Petersburg, nor in the team hotels in Chicago and St. Louis, and he didn’t have a roommate his whole first year with the Braves in Boston.50 “In Chicago, my first time in,” he told Marvin Pave of the Boston Globe, “I stayed at a black hotel, but the next time in, our traveling secretary, Duffy Lewis, had me stay in the team hotel with him. Our third time in, I had a room of my own.”51 In Boston, Jethroe stayed at the Kenmore Hotel, not far from Braves Field.

“I was lucky,” Jethroe recalled. “Everywhere I went I seemed to have the fans on my side. They kidded me about my fielding but I didn’t have rabbit ears. The fans could say what they wanted. The only confrontations I had were on the playing field.”52

While the Red Sox took more than nine years before they fielded a Black ballplayer, Jethroe seems to have been almost unreservedly welcomed in Boston. And yet, the Braves certainly hadn’t signed Jethroe because of his race. In 1950, the “non-White” population of Boston was just 5.3% of the city’s overall population. The African-American population itself was an even 5.0%. To be sure, was growing; in 1940 it had been 3.1%, and in 1960 it was 9.1%.53 Still, this was not in any way a constituency to which either the Braves or Red Sox needed to cater.

Nonetheless, one might think that the signing of a Black ballplayer would have been a major story in Boston at the time. It was not. Instead, the focus on Jethroe over the months through spring training was on his speed. The Boston press made little of his race. An online search of the Boston Herald, Boston Globe, and Springfield Union from October 1, 1949 to April 17, 1950 – the day before Jethroe’s debut – turns up 230 stories that mention “Sam Jethroe” but only 30 that mention both “Sam Jethroe” and “Negro,” the term used then the way “African American” was used in more recent times. To their credit, more than 86% of the stories made no reference at all to his race, and some of those that did were matter-of-factual, such as the Globe‘s listing of Jethroe’s prior clubs, which included the “Cleveland Buckeyes of the Negro American League.”54

It could be argued that sportswriters simply shied away from mentioning “social issues” and restricted their coverage to play on the field. However, the online search also included columnists and opinionated men such as Dave Egan of the Boston Record, who had long pushed for desegregation of Boston baseball. Egan had written back in 1945 that Boston was “freedom’s holy soil” and that “someday, the bigots of baseball will die, and men of good-will will take their places…on that day, baseball can call itself the national sport.”55

Boston’s African-American newspaper, the Boston Chronicle, reported Jethroe’s signing, but also with little fanfare. When he signed his Braves contract with GM John Quinn in New York, the Chronicle noted that “the speedy Negro outfielder had just played in the Little World Series in Indianapolis before coming to New York.” About all Jethroe himself had to say was, “I’ll let the records do the talking. I just played in the Little World Series, now I hope to get into the big one.”56

Before the traditional preseason “City Series” games against the Red Sox, the Boston Post – never referring once to his race – wrote, “Jethroe received more press interviews yesterday than all of the other Braves players combined. Sam is easy and natural with all members of the fourth estate.”57

After the first exhibition game against the Red Sox, Gerry Hern of the Post acknowledged race in a single clause. Braves fans, he wrote, “have waited a long time to make a personal appraisal of Sam Jethroe, the first colored player ever to wear a Boston uniform, and Dick Donovan, the 25-year-old Wollaston resident, who earned his letter yesterday. Sam was slightly terrific in his Boston debutante party. There were no flowers, but he slashed a couple of singles that took the strain off the Braves followers, who have not been accustomed to seeing a Braves outfielder who could hit, throw and run.”58 The novelty of Jethroe’s darker skin color was apparently on no more than a par with the novelty of a Brave from the nearby Wollaston neighborhood of Quincy, Massachusetts.

The Braves won that first game in the series, 4-1, and the Red Sox came back and won the second, 3-1, at Fenway. It was Jethroe’s first time playing in the park he’d tried out in five years earlier. Batting in the bottom of the eighth with the Braves ahead, 1-0, Ted Williams slammed a three-run homer into the right-field bullpen. Jethroe, unfamiliar with the park and anxious to catch the ball, slammed hard into the bullpen wall, in vain. The Herald noted he was “courageous and speedy” but didn’t see the need to remind readers of his darker hue. He was just another ballplayer – covered exactly the way one might wish. He was “Switching Sammy, getting plenty of encouragement from the 7,049 spectators.”59 But there was no mention of his race.

The Globe’s game story noted that Jethroe had singled in the first run. It commented on his speed at one point and observed that “Like many another big leaguer, Jethroe is superstitious…He kicks third base to and from the outfield.”60 His similarity to the other players was thus noted; there was nothing in the way of noting his difference.

The next day, in picking both the 1950 Braves and Red Sox to win the pennants in their respective leagues, the Globe‘s Harold Kaese noted race, in passing: “Sam Jethroe, Boston’s first Negro player, will display his phenomenal speed of foot by (1) scoring from first on a tap to the pitcher; (2) stealing more bases than the rest of the Braves and Birdie Tebbetts put together; and (3) dashing to the plate in time to catch his own throw from DEEP centerfield.”61

There was no mention at all of Jethroe’s race in Clif Keane’s lengthy feature on Jethroe’s very first game, which ran the morning of that game in Boston.62

The Braves opened the regular season in the Polo Grounds, where they beat the Giants, 11-4. Jethroe went 2-for-4 with an eighth-inning homer in his first game.

When it came time for Jethroe’s Braves Field debut, the Boston Traveler suggested that “Sam Jethroe’s debut in a championship game vies for attention at the Braves opener with the return of Eddie Waitkus to major-league action.” It was Waitkus’s first day back (he was playing for the Phillies) after being shot by Ruth Steinhagen in Chicago the prior July.

In the home opener, attended by the governor of Massachusetts (who threw out the first ball), the governors of Rhode Island and New Hampshire, and numerous other celebrities, Jethroe singled but his play barely rated mention in the papers. The game wound up a 2-2 tie, called due to rain in the last half of the eighth inning.

A few days later when the Brooklyn Dodgers came to town, Leslie Jones shot a photo for the Herald that depicted “five Negroes…advancing the cause of their race in baseball” — Jethroe with Dodgers Dan Bankhead, Roy Campanella, Don Newcombe, and Jackie Robinson.63

Jethroe knocked out nine hits in his first seven games in Boston. On May 6 in Cincinnati, he singled twice batting left-handed and tripled and singled batting righty.

In May, Jethroe was one of the three Boston Braves outfielders invited to a “brotherhood” dinner of the Massachusetts Council of Catholics, Protestants and Jews. Sid Gordon was the Jew, Willard Marshall the Protestant, and Sam Jethroe the Catholic.64 Sam always wore a St. Christopher’s medal.65

Almost the only newspaper story that looked at him other than as just another player was a Boston Globe feature by Ernie Roberts that ran in July, “Jethroe, Hero of Thousands at Park, Goes Unrecognized on Boston Streets.”66 According to that story, he lived on Columbus Avenue with a young couple who had invited him.

In Boston, Jethroe kept to himself. “I stayed pretty close to home. The High Hat Club on Mass. Avenue was my favorite spot. I didn’t go around to many white places – bars, movies, etc. But I met a lot of nice people. One of them was Archbishop Cushing. He would call up to make sure I got to church.”67

Jethroe had had a little trouble on the road as mentioned earlier, but it was only when visiting his native St. Louis that he could not stay at the team hotel, the Chase. And at St. Louis’ segregated ballpark, Sam’s father was forced to sit in the “Negro section” of seats.

For the most part, Jethroe roomed alone on the road. Lewis, Luis Olmo, and Earl Torgeson were his closest friends on the team. He did get some razzing at parks around the league, but said it didn’t bother him. “I don’t have rabbit ears; I don’t hear a thing. This is a country of free speech. Why not let the fans get their money’s worth?” he smiled.68

Jethroe seemed to have been welcomed by Braves fans. “The people in Boston were crazy about me,” he remembered later. “Everyone crowded around me for autographs after my first game. There was this woman who wanted to take me to dinner. A white woman. I didn’t do it because I figured that was one of the reasons they didn’t want us in the majors to begin with.”69 Jethroe had been married since November 11, 1942 to Elsie Allen, whom he had met that year at a dance in Erie, Pennsylvania.70

There was no indication that Jethroe received any razzing at Braves Field. In early 2015, there remained a few fans who had seen Jethroe break in with the Braves more than 60 years earlier. None recall racial slurs or even muttering at Braves Field. In fact, the opposite seemed to be true. A young Braves fan named Mort Bloomberg remembered, “A wave of excitement rose from the stands when he stepped to the plate (even noticeable when attendance fell sharply) because he was our hometown answer to Jackie Robinson–a self-assured threat to steal one or more bases each time he reached first…Boos when he came to bat? Never. We just wanted to see Sammy run.”71

A story in July 1950 showed that the Boston press was picking up on Braves fans’ affection for Jethroe. “Fans of Wigwam Sing Sam’s Song” was the headline on George C. Carens’ article in the Traveler. It was his base-stealing ability that captured the imagination. Yes, it was fine that Gordon, Torgeson, and Bob Elliott already had a combined 40 homers, “but the faithful followers are not happy until Sam Jethroe gets aboard. The hum when he comes up to the plate is based on the hope that he will become a base-runner…when the subject changes to the Negro center fielder’s fancy footwork on the basepaths, everyone switches to superlatives. Thousands breathe the hope that Sam can show his stuff…the sensational sorties of Jethroe have Boston all a-quiver.”72

Jack Barnes worked briefly as a vendor at Braves Field, but went to many more games as a teenage fan. He recalled more than 60 years later, “We never had too many full houses at Braves Field – maybe there’d be 10 or 12,000 of us there – but the racial question, I’m gonna tell you, there was never anybody booing or hissing Sam. We loved him. Everybody would chant, ‘Go, Sam, go.’ Sam the Jet at Braves Field was a hero. Everybody loved to see Sam run. He brought some life to the ball team. We weren’t a very fast team and he was a breath of fresh air to us. I went to a lot of games when Sam was playing and I never heard anybody…I never heard any racial slurs, or anything but admiration for Sam the Jet. Everybody loved Sam the Jet. I sat in those stands many times. I was a teenager and I was listening, and boy there was nobody booing Sam the Jet. The drunks were there at all the ballgames and they’d be raising their beer and toasting Sam as he was stealing second base. ‘Hey, Sam!!!’”73

Frank McNulty worked as the visiting team’s batboy at Braves Field from 1945 through 1949, with his first year as home batboy being 1950. Had he recalled hearing any negativity from the stands? “I don’t remember anything from the general public, anything close to discrimination.”

“I loved the Boston fans,” Jethroe said nearly 50 years later. “They used to chant, `go, go, go,’ every time I got on base. Never had a problem in Boston.”74

McNulty noted perceptively that “As far as the clubhouse was concerned, I didn’t detect anything. No group of guys that was ostracizing him or anything like that. I didn’t notice anything like that. . . the Braves in those years were somewhat divided into different groups. A number of them had come with Billy Southworth from the Cardinals. So there was that group. Bob Elliott and two or three others had come from Pittsburgh, and there was that group. And then there was Sibbi Sisti and Tommy Holmes and I think Connie Ryan, who had come though the Braves chain, through Hartford, Connecticut, and there was that group.” As to Jethroe, “He wasn’t part of any of those groups, just because he wasn’t part of those, but I don’t think that had anything to do with race at all. Jethroe was sort of a loner anyway. He was very quiet.”75

Future major-leaguer Bill Monbouquette never went to Fenway as a kid; he always went to Braves Field. He was a Knotholer. Monbo, who grew up in the Black section of West Medford, never recalls any negative reactions in the stands to Jethroe. He joked, mimicking protecting his head against a foul ball, mocking Jethroe’s defensive shortcomings, but said every time he got on first, “the fans would say, ‘Go, Sam! Go, Sam!’ He could fly. He was an exciting guy.”76

And what about opposing ballplayers? Whatever they might have done to make Jethroe’s rookie year in the majors difficult, he didn’t seem to be bothered by it. Later in Gerry Hern’s lengthy article in the Post, Jethroe was asked if he was angry at some pitchers who had thrown at his head as he’d made his way north. Jethroe “chuckled” and said, “Oh no. they’re just trying me out. They got to make a living, too. If they can drive me away from the plate, or frighten me, they’re going to do it. I don’t think there was anything else to it.”

On September 15, 1950 the Braves staged a Sam Jethroe Night for him. He’d hurt his foot the night before and had to be helped off the field, but he made it for his night. When it was first announced, he expressed embarrassment. Knowing that gifts were typically presented to those honored with a “day,” he asked instead that any money be put into a college scholarship for Negro youths. “That’s how the arrangement stands,” wrote Arthur Siegel, “and that’s why…Jethroe well rates the accolades of Boston sports enthusiasts”77 Mayor John B. Hynes did present him with a check but also a television, radio, easy chair, matched luggage set, and a week’s hunting trip to the Rangeley Lakes in Maine. The Chronicle referred to “the overwhelming kindness expressed by many fans” – hardly the sort of fan reaction that would have discouraged the Red Sox from signing a Black ballplayer. Jethroe himself was said by the paper to have been “filled with immense gratitude” and – wanting to express his appreciation with a special performance,78 – to have tried too hard in the game. He committed two errors and struck out twice in a 1-for-5 night, although he did pull off a double play late in a tight game. His speech was a short one: “Thank you. I appreciate this very much.”79

Sam Jethroe’s rookie season was a clear success. He was named National League Rookie of the Year for 1950. He’d hit for a .273 batting average (.338 on-base percentage), with a league-leading 35 stolen bases. (Jethroe’s fleet work on the base paths helped to bring base-stealing back into the game. It had not truly been in fashion at the time. That same season Dom DiMaggio led the American League with 15.) Was he stealing on the pitcher, or stealing on the catcher? “I just runs,” he told Bob Holbrook.80 His steals included an exciting first-inning steal of home on June 6 in Cincinnati. He’d scored an even 100 runs, and driven in 58. He’d hit 18 home runs. He’d committed 12 errors in 384 chances (.969). Jethroe, “weak” arm or not, led the National League in assists as a center fielder both in 1950 and 1951 and ranked second in outfield assists in 1950 and third in 1951. He received more than twice as many points in the Rookie of the Year voting as the second-place finisher, Phillies pitcher Bob Miller.

In January 1951, Jethroe attended the Boston Baseball Writers annual dinner. Howard Bryant reports that Jethroe was seated next to Eddie Collins of the Red Sox, who told the ballplayer that he was pleased to see Sam’s success. “Jethroe thanked him and without bitterness replied, ‘You had your chance, Mr. Collins. You had your chance.’”81

For the 1951 season, Jethroe recorded nearly identical stats: he again led the league in stolen bases, with the same number (35); he hit the same number of homers (18); he scored one more run (101 total); he drove in seven more runs (65); and his batting average was a few points higher (.280 with a .356 on-base percentage).

However, errors were a problem for him; he led league outfielders in errors in 1950, 1951, and 1952. “I’m ashamed I didn’t get to the eye-doctor before I did,” he told writer John Gillooly in spring training 1952; Gillooly had written that Jethroe “was almost laughed out of the league the early part of last season.”82 Joe Giuliotti is one reporter who said that Jethroe had once been hit on the head by a fly ball.83 He’d begun wearing eyeglasses in early June 1951.

In 1952, after undergoing intestinal surgery early in the year, Jethroe’s performance fell off significantly, pretty much across the board. He struck out quite a bit more and saw his batting average drop to .232 (OBP .318). The Braves finished in seventh place.

Charlie Grimm had taken over as Braves manager early in the 1952 season and he had once called Jethroe “Sambo,” which didn’t endear him to Jethroe. “Charlie Grimm was a prejudiced man and he didn’t like me,” he told the Globe in 1979.84

In 1953, the Boston Braves moved to Milwaukee. Jethroe never played for the Milwaukee Braves. On April 13, he was optioned to Toledo on 24-hour recall, but was never recalled. He hit .309 with 28 homers, but with the emergence of Billy Bruton in their outfield the Braves may have felt they were in good enough shape. On the day after Christmas they traded Jethroe, along with five other players and $100,000, to the Pittsburgh Pirates for infielder Danny O’Connell. Clearly, the Braves wanted O’Connell.

Jethroe had one at-bat for Pittsburgh in 1954. Appearing in two games, he played right field for the final two innings of the April 14 game and he pinch hit the next day, in Brooklyn, grounding into a 4-6 forceout at second base. It was his last major-league appearance.

Jethroe spent his last six seasons (1953 through 1958) in the minors, the last five of them with the Toronto Maple Leafs, averaging .280 for those five years. He also styled a little, notably parking his orchid-colored Lincoln in front of the ballpark.

He also spent one more season back in Cuban winter league baseball, 1954-55 with Cienfuegos. And he played semipro ball into the 1970s.

In his life after his playing career, Sam and Elsie operated Jethroe’s Bar and Restaurant, a steakhouse, in Erie, Pennsylvania. The business did well for several years but then in the 1990s the city’s redevelopment authority forced him to sell the property. Sportswriter Jim Auchmutey says he took out a loan and bought another place, but it was in a “tougher part of town where drug-dealing and gunplay are commonplace. Once there was a shooting death inside the bar.” The business declined rapidly, and Jethroe found himself forced to sell off his Rookie of the Year award for $3,500.85 By the end of 1994, after he’d lost his home to fire that November, he was living four blocks away in the bar.

Sam Jethroe came back to Boston twice, in 1992 and 1995, to attend player-fan reunions organized by the Boston Braves Historical Association. After the fire, the BBHA was able to raise over $2,100 and present him a check.86

At a gathering in Cleveland to honor Larry Doby, Jethroe told his former Montreal roommate Don Newcombe of the difficulties he was having. Sam and Elsie were living in the bar with two grandchildren, aged 10 and 16.

An attorney friend of Newcombe’s, John Puttock, was present and felt moved to act. The pension rule at the time was that one had to have served four full years in the majors to qualify. Jethroe had three years and seven days of service time. Arguably, Jethroe and several former Negro Leaguers had been deprived of the opportunity to start sooner than they had. “We were held back because of the color of our skin,” said Newcombe.87

A class action lawsuit was filed in U. S. District Court for the Western District of Pennsylvania contending that racial discrimination had prevented Jethroe from qualifying and receiving a major-league pension. The major leagues moved to dismiss the suit on the grounds that Jethroe had taken too long to file it, that the statute of limitations had long since expired. The suit was dismissed in October 1996.

Several people appear to have pitched in to help address the problem. One article says that one of Puttock’s friends mentioned the problem to U. S. Senator Carol Moseley-Braun (D-Illinois), who talked to Chicago White Sox owner Jerry Reinsdorf. Reinsdorf reportedly persuaded the other owners to create a special fund that was announced in January 1997, providing annual payments of $7,500 to $10,000 to former Negro League players.88

Murray Chass of the New York Times wrote that National League president Leonard Coleman and former pitcher Joe Black, who like Jethroe played in both the Negro Leagues and the majors, headed up the committee.89 Noted Negro League historian Larry Lester provided Major League Baseball with the names of qualified players and their mailing addresses.

“I can’t tell you how appreciative I am of what (the owners) have done,” said Jethroe, who by then had suffered a stroke and had other health issues.90 It did indeed offer him a little more hope, and a feeling of some validation, in his later years.

Jethroe had always been a forgiving man. Remembering being forced to stay in separate housing from his White teammates back at the beginning, he said, “You get used to it. And you let it go.”91 And after his teenage grandson, known as Sam Jethroe Jr., was killed by a drunk driver, he appeared in court and asked for mercy for the driver. “I don’t hold grudges,” he said.92

On June 16, 2001 Sam Jethroe died of a heart attack in Erie, while he was recovering from pacemaker surgery a couple of weeks earlier.

Elsie Jethroe died on May 17, 2013. She had been preceded in death by their daughter Gloria.

Sam Jethroe’s story is that of a solid if not stellar major leaguer whose fate was to have been born the wrong color for his time and his chosen profession. But if he came to the majors late, it was not quite too late; he was one of the handful of African-American players who followed Robinson and, less gifted than he, still proved that Blacks belonged in the middle tier of major leaguers as much as Whites did. Boston Globe editor Marty Nolan, in an appreciation of Jethroe written after his death, said it this way: “The lesson in equality Jethroe taught is the civil right to be less than the best.”93

Sources

In addition to the sources noted in this biography, the author also accessed Jethroe’s player file and player questionnaire from the National Baseball Hall of Fame, the Encyclopedia of Minor League Baseball, Retrosheet.org, Baseball-Reference.com, and the SABR Minor Leagues Database, accessed online at Baseball-Reference.com.

Thanks to Bob Brady and Larry Lester for a careful reading of this manuscript and very useful suggestions that improved it.

Notes

1 Boston Globe, June 21, 2001.

2 On the other hand, the 1950 National League Green Book said he “played baseball, basketball, and football for Lincoln High” and had played both as a catcher and third baseman before switching to the outfield.

3 Boston Chronicle, March 25, 1950.

4 The team was based in both Cincinnati and Cleveland in 1942, but became the Cleveland Buckeyes exclusively as of 1943.

5 Mike Copper, “Document alters what we know about Sam Jethroe,” Erie Times-News, April 9, 2010.

6 Rich Marazzi, “Sam JEThroe,” Sports Collectors Digest, November 11, 1994. In 2010, Jethroe’s grand-daughter Rachel Jethroe-Critten discovered a Mississippi birth certificate, notarized in 1987, which provided his birthdate as January 23, 1917.

7 Bob Holbrook, Complete Baseball, Fall 1950, 78.

8 Jim Auchmutey, “He’s Our Jackie,” Atlanta Constitution, June 22, 1997.

9 Michael Madden, Boston Globe, May 28, 1993.

10 Madden.

11 Larry Lester points out that the National Baseball Hall of Fame no longer uses the words “Organized Baseball” as it implies that the Negro Leagues were “unorganized.”

12 Several articles on the subject are gathered in Bill Nowlin, ed., Pumpsie and Progress: The Red Sox, Race, and Redemption (Burlington, Massachusetts: Rounder Books, 2010).

13 Jim Auchmutey, Atlanta Constitution.

14 Marazzi, Sports Collectors Digest.

15 Boston Globe, July 22, 1979.

16 Boston Globe, July 22, 1979.

17 Bob Dolgan, Cleveland Plain Dealer, September 9, 1997.

18 Jethroe to Gerry Callahan, Boston Herald, May 28, 1993.

19 David Faulkner, Great Time Coming: The Life of Jackie Robinson from Baseball to Birmingham (New York: Simon and Schuster, 1995), 102.

20 Marazzi, Sports Collectors Digest. Jessup’s name was given as Jim Jessup in the article, but his actual name was Joseph Gentry Jessup.

21 Dolgan.

22 Roberto Gonzalez Echeverria, The Pride of Havana: A History of Cuban Baseball (New York: Oxford University Press, 1999), 54, 68. See also Jorge S. Figueredo, Cuban Baseball: A Statistical History, 1878-1961 (Jefferson, North Carolina: McFarland, 2003), 296.

23 Jorge S. Figueredo, Who’s Who in Cuban Baseball 1878-1961 (Jefferson, North Carolina: McFarland, 2003), 379. The strikeout total is reported in Figueredo’s Cuban Baseball: A Statistical History, 1878-1961 on page 308.

24 Auchmutey.

25 The sum was reported by Dolgan. The Biographical Encyclopedia of the Negro Leagues says that Jethroe took a paycut, from $700 a month with the Buckeyes to $400 a month with the Montreal Royals. Thompson scouted Jethroe on the recommendation of Pittsburgh sportswriter Wendell Smith, per Ken Smith of the New York Daily Mirror, December 1, 1949. SABR’s Scouts Committee credits both Thompson and Branch Rickey Jr. for the signing.

26 Dolgan.

27 New York Daily Mirror, December 1, 1949.

28 Dolgan. The story was also told by Arthur Daley in the New York Times, September 2, 1949. Years later Richards said it was not true. Buffalo Courier-Express, July 13, 1965.

29 Auchmutey.

30 New York Times, September 2, 1949.

31 New York Amsterdam News, April 9, 1949, 27.

32 New York Times, October 2, 1949.

33 New York World-Telegram, October 2, 1949. On June 2, the Buckeyes had denied that Jethroe had been sold to the Boston Red Sox. See Associated Press story June 2, 1949. The New York Times later reported (November 10, 1950) that the Braves had, perhaps counting the value of the players, paid $137,500 for Jethroe.

34 Mabe “Doc” Kountze, Fifty Sports Years Along Memory Lane (Medford, Massachusetts: Mystic Valley Press, 1979), 24. Quinn’s ballpark hosted a July 6, 1938 game between the Boston Royal Colored Giants and the traveling House of David team.

35 Boston Herald, October 2, 1949.

36 Washington Times Herald, October 6, 1949.

37 See Billy Southworth’s remarks as in Associated Press dispatches on October 6, 1949.

38 New York World-Telegram, April 8, 1950.

39 Gus Steiger, New York Daily Mirror, October 4, 1949.

40 Dan Daniel, The Sporting News, March 29, 1950.

41 Marvin Pave, Boston Globe, August 29, 1997.

42 Bob Ajemian, The Sporting News, March 29, 1950.

43 Harold Kaese, The Sporting News, March 29, 1950.

44 Dan Daniel, New York World-Telegram, April 1, 1950.

45 Bob Holbrook, Complete Baseball, Fall 1950, 78.

46 Author interview on January 1, 2015 with John Delmore, recounting a personal memory.

47 Boston Chronicle, April 8, 1950.

48 Boston Chronicle, April 8, 1950.

49 Larry Whiteside, Boston Globe, July 22, 1979.

50 “It wasn’t all bad,” he told Whiteside. “We actually made money on expenses staying in private homes.”

51 Pave, Boston Globe, August 29, 1997.

52 Whiteside, Boston Globe, July 22, 1979.

53 Campbell Gibson and Kay Jung, “Historical Census Statistics On Population Totals By Race, 1790 to 1990, and By Hispanic Origin, 1970 to 1990, For Large Cities And Other Urban Places In The United States,” U.S. Census Bureau Population Division Working Paper No. 76, February 2005, Table 22.

54 Boston Globe, October 12, 1949.

55 Dave Egan, “Day of Reckoning Due for Baseball,” Boston Record, August 10, 1945.

56 Boston Chronicle, October 15, 1949.

57 Boston Post, April 15, 1950.

58 Boston Post, April 16, 1950.

59 Will Cloney, Boston Herald, April 16, 1950.

60 Boston Globe, April 16, 1950.

61 Boston Globe, April 17, 1950.

62 Boston Globe, April 21, 1950.

63 Boston Herald, April 25, 1950.

64 Boston Traveler, May 26, 1950.

65 Marazzi, Sports Collectors Digest, 111.

66 Boston Globe, July 9, 1950.

67 Whiteside. Boston Globe, July 22, 1979.

68 Boston Globe, July 9, 1950.

69 Auchmutey, Atlanta Constitution, June 22, 1997.

70 Sentinel, April 13, 1953.

71 Mort Bloomberg email to author, August 19, 2014.

72 Boston Traveler, July 10, 1950.

73 Author interview with Jack Barnes, January 1, 2015.

74 Pave, Boston Globe, August 29, 1997.

75 Author interview with Frank McNulty, January 15, 2015. Longtime fan John Delmore said, “Braves fans were very loyal, to a T. We were the second-class citizens in Boston, so to speak. We loved the Braves. Even in the bad times, we hung in there with them. The Red Sox and Yawkey were the spoiled millionaires and we were the lunch-pail crew. All I have is positive memories of Sam Jethroe. I don’t remember anybody, anybody at all, ever, bringing up race with Sam Jethroe. None! Robinson took the brunt of it when he broke in. I think by the time Sammy got there with the Braves, a lot of that stuff had dwindled. I’m not sure whether he might have taken some heat in some other ballparks, but he never got any bad vibes in Boston, I can tell you that. If anything, it was just the opposite. They loved the guy.” Author interview with John Delmore, January 1, 2015. Delmore added, “By that time, the issue had quieted down. I remember when Jackie Robinson played his first game. It was against the Braves. I was in the eighth grade at St. Theresa’s in Somerville. We had a P.A. system in all the classrooms and the head nun brought a radio to school that day. She put the Braves-Dodgers game on because Jackie Robinson was playing his first game, breaking the color barrier.” Other longtime Braves fans who concurred with the welcome reception Jethroe had in Boston are Mort Bloomberg (emails to author on January 12 & 13, 2015) and John Quinn (son of Braves GM Bob Quinn) in an interview with the author on January 20, 2015.

76 Author interview with Bill Monbouquette, August 24, 2014.

77 Boston Traveler, September 14, 1950.

78 Boston Chronicle, September 23, 1950.

79 Boston Post, September 16, 1950.

80 Bob Holbrook, Complete Baseball, Fall 1950, 78. It may be worthy of note that both rookies of the year in 1950 played for Boston teams; Walt Dropo of the Red Sox was the American League Rookie of the Year. As to the “I just runs” quotation, Bob Brady suggests that “it seems inconsistent with other direct quotes used in [Holbrook’s] piece where Jethroe’s use of the language does not reflect a ‘Stepin Fetchit’ dialect.” E-mail from Bob Brady, December 16, 2014.

81 Howard Bryant, Shut Out: A Story of Race and Baseball in Boston (New York: Routledge, 2002), 33, citing the personal papers of Ann Muchnick. Bryant paints a far-from-benign portrait of Eddie Collins on the subject of race. See pages 28-30 and 43-44.

82 Boston Record, April 9, 1952.

83 Author interview with Joe Giuliotti on September 30, 2014. Giuliotti’s career started in the 1970s, so this was not something he had personally witnessed.

84 Larry Whiteside, Boston Globe, July 22, 1979. Ralph Evans came to know Jethroe through Boston Braves Historical Association gatherings and has had him as a guest in his home. “I do know from talking to Sam that when he arrived at the field, he was talking with Billy Sullivan and Billy Sullivan said, ‘I understand that you don’t like the nickname Sambo’ and he said, ‘No, I don’t,’ and Billy Sullivan said, ‘Okay, we won’t call you Sambo’ – and they made sure that that wasn’t done. I don’t remember anybody saying anything bad about him.” Author interview with Ralph Evans, January 15, 2015. The one negative memory Jethroe had about his time in Boston related to the astigmatism he developed, which led to some embarrassing fielding incidents before he got his eyeglasses. There were jokes about his eyesight, but they were not one which bore an additional burden of race.

85 Auchmutey.

86 Boston Braves Historical Association Newsletter, Summer/Fall 1995.

87 Scott Kauffman, “Life among the cinders,” USA Today, February 22-28, 1997. The old pension rule had been five years, but an agreement reached on February 25, 1969 reduced the pension time to four years. (See Washington Post, February 26, 1969.) This still left Jethroe and some others short of the four years required.

88 Atlanta Journal, June 22, 1997.

89 Murray Chass, New York Times, January 20, 1997.

90 New York Daily News, January 20, 1997.

91 Cleveland Plain Dealer, July 17, 1995.

92 Atlanta Journal, June 22, 1997.

93 Nolan, Boston Globe, June 21, 2001.

Full Name

Samuel Jethroe

Born

January 23, 1917 at Lowndes County, MS (USA)

Died

June 16, 2001 at Erie, PA (USA)

If you can help us improve this player’s biography, contact us.