Jackie Robinson: The Best Athlete on the West Coast

This article was written by Vince Guerrieri

This article was published in Jackie Robinson: Perspectives on 42 (2021)

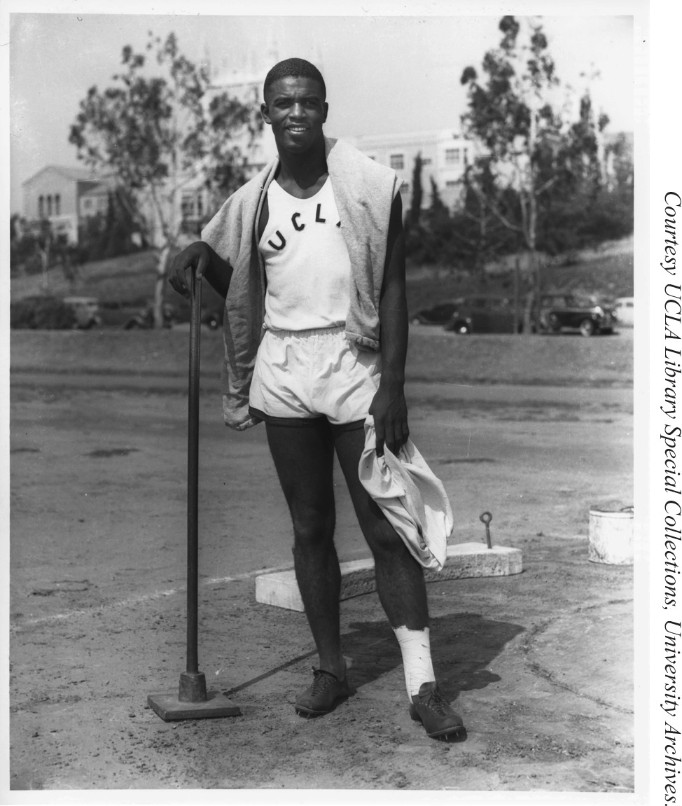

Jackie Robinson in his UCLA track uniform. (UCLA LIBRARY SPECIAL COLLECTIONS)

Once he got to the major leagues, it didn’t take long for Jackie Robinson to establish his credentials as a Hall of Fame baseball player.

He was named Rookie of the Year in 1947, and MVP two years later. His skill at baseball belied a tremendous athleticism. In fact, in the years leading up to American involvement in World War II, he had distinguished himself in several sports.

Thousands had filled stadiums to watch Robinson’s athletic prowess as an amateur in Southern California – not in baseball, though. Although Robinson lettered in baseball at UCLA, it was probably the weakest of the four sports in which he excelled. Rather, they’d file into the Rose Bowl or the Coliseum to watch him play football. Robinson was also a national champion long jumper, and played basketball in college as well.

But he went on to be a trailblazer for the Brooklyn Dodgers, the year after two college teammates integrated pro football. When it came to pro sports, major-league baseball was king. The NBA didn’t exist, and the NFL at the time was still regarded in many ways as a fly-by-night, pass-the-hat league, dwarfed in popularity by the college game. Race aside, Robinson could have gone professional in any sport. He was, as Newspaper Enterprise Association sportswriter Don Sanders called him, “the best all-around athlete on the coast.”1

Robinson was born in Cairo, Georgia, in 1919, but his family moved to Southern California a little more than a year later. He attended John Muir Technical High School in Pasadena, where he participated in the glee club in addition to four sports: football, baseball, basketball, and track, competing in what was then called the broad jump but is more frequently called the long jump.

In baseball, Robinson played shortstop at Muir – except for one year when he played catcher to fill a need – and, largely on the strength of his skills, in 1935 the team received an invitation to the celebrated Pomona Tournament, an enormous event, with an appearance by Governor Frank Merriam, comedian Joe E. Brown as the banquet speaker, and Mickey Rooney throwing out the first pitch of the championship game. It was the first time a team with African-American players was allowed to participate. (However, while his White teammates were able to find lodging, Robinson had to return home to Pasadena nightly.) Robinson stole a tournament-high 11 bases.2

Muir returned to the tournament the following year and ended up facing another future Hall of Famer: Ted Williams and San Diego Hoover High School. In that game, Robinson had three hits and stole home, but Hoover won 8-7, as Williams hit a 450-foot home run.3 Robinson received additional accolades in the fall of 1936, when he won the junior singles title of the Pacific Coast Negro Tennis Tournament.4

When Robinson came to Pasadena Junior College, after graduating from Muir, he might have been best known as the younger brother of Mack Robinson, who’d won the Silver Medal in the 200-meter dash, finishing second to Jesse Owens, at the 1936 Olympics in Berlin.

Jackie Robinson would soon prove himself in his own right. In his autobiography I Never Had It Made, Robinson recalled competing in the broad jump in Pomona one morning, setting a record, and then driving to Glendale for an afternoon baseball game, where he played shortstop as Pasadena won the championship.5 Duke Snider, who grew up in Compton (among his high-school friends was future NFL Commissioner Pete Rozelle), recalled watching Robinson play a game in Pasadena, leave the field during a game to go to the nearby track, compete in the broad jump – still in his baseball uniform – and return to the ballgame.6

In his second year at Pasadena, Robinson scored 131 points on the gridiron and gained more than 1,500 yards – drawing thousands of fans to junior-college games – and set a juco record in the broad jump and was all-conference in basketball. His baseball performance was almost an afterthought, but he batted .417.7

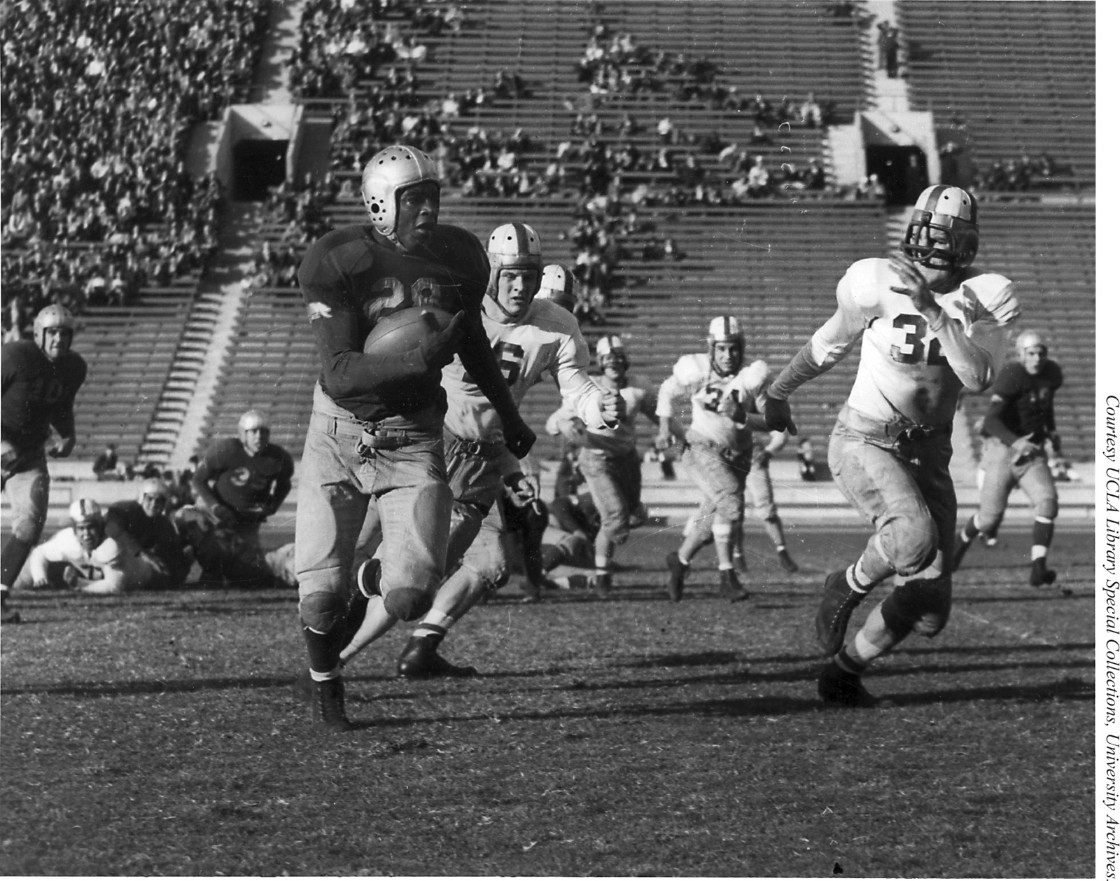

Robinson had his pick of colleges to attend after Pasadena, but he ended up staying close to home, going to UCLA. (No doubt a factor was the Bruins hiring a new coach, longtime assistant Babe Horrell, a Pasadena native.) Upon Robinson’s arrival at UCLA, it was treated as almost a sure thing that he’d start on the football team. “Pasadena and Westwood faithfuls pin great hopes on Jackie and predict great things on his passing and elusive running that have made him the greatest open field runner in junior college circles,” the UCLA Daily Bruin wrote in its 1939 registration edition.8 Running backs Robinson, Woody Strode, and Kenny Washington were referred to as the Gold Dust Trio.9

It didn’t take long for Robinson to live up to his reputation. After just four games, the Daily Bruin touted him as “the toe-dancing tornado!” and said he was better than the old Galloping Ghost himself, Red Grange.10 And that was before Robinson led the Bruins to a 16-6 win over Oregon, catching a 66-yard touchdown pass from Washington and running 83 yards for another score, prompting Ducks coach Tex Oliver to say, “You need mechanized cavalry to stop him. He runs as fast at three-quarter speed as the average player does at top speed, and he still has that extra quarter to draw upon.”11

The season culminated in a game against Southern California that drew more than 103,000 fans – then a record for a college football game – to the Coliseum. With a bid to the Rose Bowl on the line, the teams battled to a scoreless tie, as a late drive by the Bruins stalled, leaving them, as the campus paper said, “Two yards from the Rose Bowl!”12 USC got the bowl bid, but the Bruins still finished 6-0-4 – their first undefeated season – and were voted seventh in the Associated Press poll.

Originally, it was thought Robinson would concentrate on baseball in the spring, forgoing basketball and track (his Olympic aspirations came to a halt with the onset of World War II, leading to the cancellation of the 1940 Games), but it was announced shortly after the basketball team started practice that Robinson would be part of it.13 Robinson scored 148 points in 12 games, good enough to lead the Southern Division of the Pacific Coast Conference. However, he opted not to participate in track at UCLA in 1940, a move that coach Harry Trotter said altered the balance of power in the league.14

A week after the basketball season ended, Robinson was playing in an exhibition for the baseball team, where he got four straight hits and stole four bases, including home. “The game had marked the first time Robinson has stepped on a diamond since last August,” Johnny Beckler wrote in the Daily Bruin. “And the amazing rapidity at which he got his batting and fielding eye speaks well enough for his ability as a baseballer.”15

Jackie Robinson playing football for UCLA in 1939. (UCLA LIBRARY SPECIAL COLLECTIONS)

In Robinson’s first varsity game with UCLA, he demonstrated his talent as well as his competitive nature. In a marathon against Cal that was tied, 13-13, going into the ninth, Robinson was called to pitch as darkness started to settle in Westwood. He threw strikes – and then threw a pitch over the backstop, saying he couldn’t see. Chaos ensued, with the umpire finally calling “no game.”16 (The Bears won the next day.)

Robinson’s lone season on the Bruins varsity baseball team was an unspectacular one, with a .097 batting average. His defense and baserunning, however, kept him in the lineup. Once the baseball season was over, he competed with the track team – while continuing to participate in spring practice for the football team – winning the broad jump at the Pacific Coast Conference (now the PAC-12) and NCAA tournaments. His win at the NCAA tournament in Minnesota made him and his brother the first siblings to each win NCAA titles, and were it not for the fact that the Olympics were canceled in 1940 (and then again in 1944), Jackie might have followed brother Mack as a medalist. With his track participation, Robinson became the first athlete to letter in four sports at UCLA – and he’d done it all in the same academic year!

Hopes were high going into the 1940 football season. Robinson was a bright spot, leading the team in passing (444 yards), rushing (383), and scoring (36 points; in addition to being used in the backfield, he also kicked extra points). But the Bruins lost their first seven games before beating Washington State at the Coliseum in what turned out to be their only win of the season.

He played basketball again, and again won the league scoring title, this time with 133 points. But in spring 1941, Robinson left UCLA before graduating, believing “no amount of education would help a black man get a job.”17 He went to work for the National Youth Administration before that New Deal program was shuttered as war loomed. Robinson played on a variety of all-star teams, from a baseball game of California all-stars (including future major-league pitcher Ewell Blackwell) as a USO benefit18 to the College East-West All-Star Game in Chicago against the NFL champion Chicago Bears. In that game, another brainchild of Chicago Tribune sports editor Arch Ward, who also organized the first major-league baseball All-Star Game, Robinson caught a touchdown pass from Charley O’Rourke of Boston College, but the Bears rolled to a 37-13 victory behind the passing of Sid Luckman, under the lights at Soldier Field.

Shortly thereafter, Robinson made his first foray into professional sports – the Honolulu Bears of the Pacific Coast Professional Football League. After the 1941 football season, Robinson, who had a construction job for a company near the US naval base at Pearl Harbor, returned to California. He departed Hawaii on December 5, 1941. While he was on the ship home, he received news that Pearl Harbor had been attacked and that war was declared. The Army beckoned, and after that, professional baseball, first with the Kansas City Monarchs of the Negro Leagues and then with the Dodgers.

Among the qualifications Dodgers general manager Branch Rickey sought in the first player to integrate the White major leagues was that he had to be a college man, who had played for and against integrated teams, and Robinson fit the bill because of his time in Pasadena and UCLA. Robinson made his debut in the Dodgers organization in 1946 – the same year his former teammates Washington and Strode integrated the National Football League, for the new Los Angeles Rams. (The Rams, relocated from Cleveland, had to integrate to be able to play at the Coliseum; they were quarterbacked by Bob Waterfield, who arrived at UCLA from Van Nuys High School in the fall of 1941, just missing Robinson.) Robinson made his debut with the Dodgers in 1947, and became a key part to some of the best baseball teams ever, the famed Boys of Summer.

Robinson retired after the 1956 season. The next season would be the Dodgers’ last in Brooklyn. The West Coast loomed, and the Los Angeles Dodgers would debut in 1958 at the Coliseum – the site of Robinson’s greatest exploits as a college athlete.

VINCE GUERRIERI likes to think of himself as a sportswriter who’s gone straight. He’s spent more than 20 years in newspapers, and has bylines in pub-lications like Smithsonian, Mental Floss, Popular Mechanics, Deadspin, and the Hardball Times. He’s the author of two books on sports history.

Notes

1 Don Sanders, “Towering Oregon Team Is Coast Court Choice,” Santa Cruz (California) Evening News, January 6, 1941: 5.

2 cifss.org/wp-content/uploads/2018/10/CIFSS-History-111-20-30-Pomoma-Tournament.pdf.

3 Jim McConnell, “Pomona Tourney Was Historic,” insideso-cal.com/tribpreps/2009/03/03/mcconnell-pomon/.

4 Jason Lewis, “Black History: Jackie Robinson Excelled at a Higher Level in Other Sports,” Los Angeles Sentinel, July 14, 2011. lasentinel.net/black-history-jackie-robinson-excelled-at-a-higher-level-in-other-sports.html.

5 Jackie Robinson, I Never Had It Made (New York: G.P. Putnam’s Sons, 1972), 22.

6 Shav Glick, “Legend of the Fall,” Los Angeles Times, April 14, 2005. latimes.com/archives/la-xpm-2005-apr-14-sp-robinson14-story.html.

7 Hank Shatford, “Jack Robinson – Better Than Grange,” Daily Bruin, October 27, 1939: 3.

8 “Transfers Bolster Varsity,” Daily Bruin, registration edition, fall 1939: 5.

9 Sometimes called Goal Dust. In fact, when Strode – who went on to fame as an actor – wrote his autobiography, he titled it Goal Dust.

10 Shatford, “Jack Robinson – Better Than Grange.”

11 Glick, “Legend of the Fall.”

12 Milt Cohen, “Bruins, Trojans Battle to Scoreless Tie,” Daily Bruin, December 11, 1939: 1

13 “Robinson Slated as Quintet Hope,” Daily Bruin, October 9, 1939: 3.

14 Hank Shatford, “Loss of Robinson, Strode shatters ’40 track hopes,” Daily Bruin, registration edition: 4.

15 Johnny Beckler, “UCLA, Cal in Conference Opener Today,” Daily Bruin, March 11, 1940: 3.

16 Hank Shatford, “League Opener Ends in Near-Riot,” Daily Bruin, March 12, 1940: 1.

17 I Never Had It Made, 23.

18 “All-Star Teams Tangle Tonight,” San Pedro (California) News-Pilot, August 9, 1941: 7.