Jamestown, North Dakota, in 1932: Racial reconciliation, and Hall of Fame competition

This article was written by Thomas E. Merrick

This article was published in The National Pastime: Major Research on the Minor Leagues (2022)

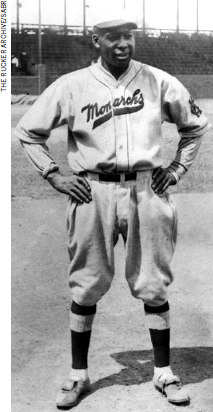

Wilbur Rogan, pictured here second from left in the front row, compiled a 20-3 pitching record for Jamestown in 1932, batting .315 and leading the team in RBIs. (SABR-Rucker Archive)

Jamestown, North Dakota, fielded Class D minor-league teams in 1922 and 1923, and again in 1936 and 1937.1 But between those two excursions into affiliated baseball, the game flourished in the city. The Jamestown Baseball Association (JBA) turned the prairie town of 8,000 into a baseball hotbed, treating its patrons to integrated semipro baseball against topflight competition.2 The JBA succeeded by hiring three or four well-known players each year to lure fans from a 50-mile radius, and then adding the best local players to “keep good baseball alive in the community.”3

Among Jamestown’s semipro teams, the 1932 club deserves recognition for its stellar record, famous opponents, and a star player who would later be enshrined in the National Baseball Hall of Fame. Beyond that, the team merits honor for reversing an unjust racial policy.

Semipro baseball of the 1930s may have equaled top minor league classifications. Minor-league pay was often low, so a ballplayer who could pocket more money with an independent team like Jamestown might jump.4 Another source of talent—Black players—became available even before the 1929 stock market crash because “the fragile structure of the Negro leagues had already collapsed.”5

While the major leagues and all baseball teams affiliated with them remained firmly segregated until after World War II, many small-town, independent teams in the Upper Midwest—starting with Bertha, Minnesota, in 19246—were integrated. Black teams had been touring the area for years, so the talent and character of Black players was widely known. Then as now, strength up the middle was important to winning, so Black players—usually a pitcher and catcher—were recruited for those positions to gain competitive advantage. A winning team gave the citizenry bragging rights over nearby towns, and drew more people to the games—people who bought tickets and concessions, but who also filled-up at a local service station, or purchased something from a local merchant.

Jamestown’s on-field success in 1932 owes much to the pitching and hitting of Bullet Rogan, who had both pitched and played outfield for the Kansas City Monarchs since 1920, when Kansas City became an original member of the Negro National League (NNL). Rogan—who won more league games than any other NNL pitcher—compiled a 20-3 record with Jamestown. When he was not on the mound for Jamestown, Rogan played the outfield or first base, and in 39 games he hit .315 with 11 home runs, and a team-leading 51 runs batted in.

Jamestown first integrated its team in 1929, when manager O.K. Butts obtained the services of catcher Roosevelt “Chappie” Gray and pitcher Fred Sims. One reason Jamestown could integrate its team—and host Black traveling teams—was that the Central Hotel, located near Jamestown’s train depot, was integrated. Over the years, the Central Hotel housed Black ballplayers and musicians, the Harlem Globetrotters, and other Black travelers.7

Gray, who had played one game in the NNL in 1920, soon moved on, but Sims played the entire 1929 season, sharing pitching duties with Swede Risberg of Black Sox infamy. Sims, Risberg, and Joe Johnson, another Black pitcher, were all on Jamestown’s roster in 1930 when it finished 31-16 against a tough schedule.

But on April 9, 1931, the JBA made a stunning announcement. The Jamestown Sun notified the public that Jamestown would have an all-white team, with the notice: “The Jamestown Baseball Association announces that because of the many requests from the fans Jamestown will have an all-white team this year and have secured the services of a white battery….”8

The new players, the paper continued, “have been recommended to the management as being clean cut young men of good habits and exceptional playing ability.”9 That statement implies the “all-white policy” was a response to problems caused by Sims or Johnson. Not so.

There is no evidence of mischief by Sims or Johnson, and Sims was greeted warmly when he returned to Jamestown in 1932 with the Corwith (Iowa) Nighthawks.10 Further, when the “all-white policy” was reversed, Rogan was favorably compared to John- son—a comparison that surely would not have been made if Johnson had left Jamestown under a cloud.

The JBA’s decision cannot be excused by the depressed economy. The integrated 1929 team turned a $522.14 profit.11 No financial information is available for the 1930 team—playing after the Stock Market Crash—but newspaper reports make no mention of waning attendance. The JBA hired White semipros from Canada, Seattle, and Minneapolis for 1931, and must have incurred similar expenses no matter the players’ skin color.

The Sun announcement reveals the absurdity of race relations in 1930s America. Could baseball fans really veto common sense and liberty? The Kansas City Call, a Black-owned newspaper, decried “the damnable outrage of prejudice” in sports.12 The JBA’s action can bear no other label.

On March 16, 1932, the JBA held its first stockholders’ meeting of the new year to elect a board of directors. E.A. Moline and George Staples were elected to replace two men who had moved away, and they joined eight holdovers as directors. The board scheduled another meeting for March 18 to elect officers, and plan for the upcoming season.13

No report of the March 18 board meeting is available, but the “all-white policy” was presumably reversed, and the team re-integrated. The next Sun article details an April 20 JBA meeting at which Butts was retained as manager, Opening Day was set for May 8 against St. Paul Northern Pacific, and the hiring of Rogan to pitch, Charles Hancock to catch, and Marty O’Neil to play shortstop was approved.

The Sun reporter noted Rogan’s Monarchs pedigree, but saved his praise for Hancock and O’Neil. Hancock was described as a “big colored catcher,” familiar to Jamestown fans from his visits with Gilkerson’s Union Giants, and Lone Rock, Illinois. “With him and Rogan there will be a good colored battery that will draw crowds.”14 O’Neil, from Minneapolis, returned from the 1931 team, and readers were reminded that he could “cover short as fast as lightning and everyone will be glad to see him come back.”15

The Sun again listed the JBA board of directors, and some names had changed since March. Three new members—Floyd Mooney, Butts, and W.C. McColloch—replaced previously listed directors, meaning five of the 10 directors from 1931 were gone. Moline was elected president, McColloch vice-president, Staples treasurer, and Mooney Secretary. All the JBA officers for 1932 came from the five new members. Did differences over the “all-white policy” trigger re-organization of the board?

Butts recruited Ray Mock from St. Paul for second base, and completed the roster with local players after tryouts. Many of those selected had played with the team in past years. Twenty-year-old Al Schauer made the team, and later joined the Northern League’s Wausau (Wisconsin) Lumberjacks from 1936 through 1938.

Uncertainty about the season with the Kansas City Monarchs led Rogan to sign with Jamestown. (SABR-Rucker Archive)

While the door in Jamestown had swung open for Rogan, he would not have spent the summer in North Dakota except for developments in Kansas City. It was unclear if Monarchs’ owner J. Leslie Wilkinson would muster a team in 1932. He had withdrawn Kansas City from the NNL after losing money during the 1930 season.16 In 1931 Wilkinson had launched the Monarchs on a barnstorming tour, using an ingenious portable lighting system to play rare, and lucrative, night games. Now, Wilkinson had leased the lights to the House of David.17 He was attempting to organize a new league, and toying with the idea of moving the Monarchs to Chicago.18

Wilkinson’s indecision left Rogan in the lurch. Rogan had missed most of 1931 with an illness, and was approaching age 39.19 He knew he could still play baseball, but he lacked a team. Hancock, who wintered in Missouri, offered him one.

Hancock informed Rogan of his agreement to catch for Jamestown, and invited Rogan to join him there to pitch.20 Hancock must have been convincing, and the JBA must have met Rogan’s financial demands, because Rogan signed on, and his hiring was announced. He accompanied Hancock to Jamestown in time for a May 1 scrimmage.

Rain canceled Jamestown’s May 8 Opening Day, but the season got underway against Fargo-Moorhead on May 15 with pomp and ceremony. Both teams paraded in uniform down Fifth Avenue to Jamestown’s City Ballpark, led by Jamestown’s City Band. Players from both squads were introduced to the crowd, and JBA president Moline threw out the ceremonial first ball.

Rogan started on the mound, and surrendered an unearned run in the first, and two more unearned runs in the third, when Hancock threw a bunted-ball into right field. But Rogan sailed through the final six innings to win, 5-3, on a six-hitter. He struck out seven, walked no one, and charmed Jamestown’s baseball faithful.

Jamestown won its first seven games before losing, 7-6, to Northern Pacific in a make-up of the rained- out opener. Jamestown’s winning streak included two wins over the House of David during Memorial Day weekend. A big crowd cheered as Rogan homered and pitched Jamestown to victory on Sunday, and a full house on Monday witnessed him stroke two home runs while playing right field. House of David had mauled Jamestown, 20-1, under the lights in 1931.21 So the two wins impressed the Sun, which declared, “Jamestown beat probably the strongest team that the boys will meet this season.” 22

By the end of July, Jamestown had a flattering 28-4 record, but was about to face a formidable foe with an even better record: the Kansas City Monarchs. While Rogan had been endearing himself to Jamestown, Wilkinson used the rental income from his portable lights to finally assemble the Monarchs in early July. Wilkinson found quality ballplayers in mid-summer because the Homestead Grays fell a month behind on payroll, causing eight Grays—including future Hall of Fame inductees “Cool Papa” Bell and Willie Wells—to jump to the Monarchs.23 Despite starting late, the Monarchs played over 150 games in 1932, including an August 1 stop in Jamestown.

Posters around town promoted the game, and the Sun did its part by informing readers of the Monarchs’ championships, and Rogan’s long connection to Kansas City as player and manager. The Sun recognized that several Monarchs would be major-leaguers if eligible, and compared the Monarchs to the New York Yankees for their dominance of the Colored League24

The Monarchs had just swept three games in Winnipeg, Manitoba, and brought a 20-game winning streak to town.25 Rogan had pitched Jamestown past Duluth on Thursday (his 39th birthday), and on Sunday he topped Northern Pacific before a large crowd. For this Monday evening game Rogan—facing the Monarchs for the only time in his long career26— guarded first base.

Jamestown started back-up pitcher Al Cassell, a Jamestown College coach. Butts borrowed Thomas Gallivan, a 20-year-old Northern Pacific hurler, to come to Cassell’s rescue if needed. Birthum Hunter threw for Kansas City.27

Neither team scored until the third, when, with two down, consecutive hits by Bell, Newt Allen, Wells, and Tom Young tallied three Monarchs’ runs. In the fifth, Bell stole home, and Allen scored on a hit by Young, to build the lead to 5-0. In the sixth, the Monarchs scored on a Jamestown throwing error, making it 6-0. Gallivan blanked Kansas City in its final two at-bats.

Jamestown collected only four hits. Schauer and George Deeds both singled in the fourth, but did not score. In the seventh, Hancock singled, and, with one out, and a 2-and-1 count, Rogan slugged one over the fence, cutting the margin to 6-2. That was the final score. Hunter struck out 10 and walked one. In the vernacular of the day, the Monarchs were acclaimed as “One of the fastest teams ever to step on [the] local diamond.”28

On August 14, in the final game on Jamestown’s schedule, Rogan hit a grand slam, drove in six runs, and pitched a six-hitter, defeating the Huron (South Dakota) Boosters, 9-3. It was Rogan’s 20th win, and raised Jamestown’s record to 32-7, including 25-6 at home. Jamestown had won 11 of 12 from intrastate foes, prompting the Sun to crown Jamestown as the 1932 North Dakota champion.29 After the Huron game, JBA director William Hall thanked patrons, and expressed his hope that next year’s team would be as good or better.

As it turned out, the team had one more appointment on the year. Manager Butts announced in September that Jamestown would entertain the Philadelphia Athletics, who would arrive on October 2, do some hunting, and play Jamestown on October 4. Since Rogan had returned to Kansas City immediately after Jamestown’s last game (and would be touring Mexico with the Monarchs30) Butts recruited “Lefty” Brown of the Cuban Stars to pitch. Gilkerson’s Red Haley replaced Mock at second base; the rest of the team was intact.

It was not the Philadelphia Athletics, but the Earle Mack All-Stars—fresh from drubbing Sioux Falls, South Dakota, 16-1—that arrived in town. A crowd of 1,800— paying $1 for reserved seats, and 75¢ for general admission—was entertained by the clowning of Nick Altrock and Al Schacht, and “one of the best exhibitions 31of baseball ever witnessed in the northwest.”

Neither Jamestown’s Brown nor Detroit’s Earle Whitehill allowed a run in the first three innings, but both teams scored in the fourth. Red Kress of the White Sox singled sharply to left, and when the ball rolled through Lloyd Withnell’s fingers, Kress raced to third. The A’s Bing Miller lofted a fly to left, and Kress beat Withnell’s throw home for a short-lived 1-0 lead.

Cleveland’s Clint Brown coaxed two groundouts in Jamestown’s half of the fourth before Hancock singled. Hancock scored ahead of Haley, who shot a liner between Kress and third base, and sped around the basepaths for an inside-the-park home run.

Jamestown lost its 2-1 lead in the seventh. After Washington’s Joe Judge walked, Detroit’s Charlie Gehringer slammed a liner to left field, and Withnell made a spectacular catch, sending Judge scrambling back to first. Heinie Manush’s grounder forced Judge at second, and Cincinnati’s left-handed Babe Herman (who went 4-for-4) rocketed a ball over the right-field fence, over the street, and into the James River, putting Mack’s team ahead, 3-2. In the ninth, Philadelphia’s 25-game-winner Lefty Grove preserved the win, using 11 pitches to strike out Jamestown’s three batters. Mack’s four pitchers totaled 13 strikeouts.

Mack’s team visited a hospitalized teenager the morning of the game, and after the contest posed for pictures and signed autographs. Both teams, along with a champion American Legion team, were feted that evening at a banquet attended by 150.32 The season was complete.

All summer Jamestown’s fans witnessed great baseball, and great baseball players. Rogan was posthumously inducted into the National Baseball Hall of Fame in 1998, and five other Hall of Fame inductees: Bell, Gehringer, Grove, Manush, and Wells—all in their prime—took the field for the opposition. Years later, Hancock remembered, “Rogan was a grand old man. [Jamestown fans] just fell in love with him. He could really pitch and hit.”33 What a glorious time to come to the ballpark.

THOMAS MERRICK is a retired North Dakota District Court judge, and an Air Force veteran, currently living in Buffalo, Minnesota. He attended his first major league game on July 9, 1961, at Briggs Stadium with his father and brother, and watched his father’s beloved Detroit Tigers sweep a doubleheader from the Los Angeles Angels. He has been a SABR member since 2000 and frequently contributes essays to the SABR Games Project. His article, “Swede Risberg’s journey to Jamestown,” appeared in the June 2019 Black Sox Scandal Research Committee Newsletter. Among his many blessings are his wife Pamela, their three children, and their two granddaughters.

Notes

1. The Jamestown Jimkotans were part of the Dakota League in 1922 and the North Dakota League in 1923, and the Jamestown Jimmies were a Northern League Franchise in 1936-37. The semipro teams did not have a nickname, although after purchasing grey uniforms with red trim, caps, and socks in 1931, some fans referred to them as the Red Sox.

2. The population from the 1930 census was 8,187; the 2020 census 15,849.

3. “Baseball Getting into Full Swing for Season’s Work,” Jamestown Sun, April 19, 1930: 6.

4. Kyle P. McNary, “Double Duty” Radcliffe: 36 Years of Pitching & Catching in Baseball’s Negro Leagues (St. Louis Park, MN: McNary Publishing, 1994).

5. Janet Bruce, The Kansas City Monarchs: Champions of Black Baseball (Lawrence, KS: University Press of Kansas, 1985).

6. Peter Gorton and Steven R. Hoffbeck, “John Donaldson and Black Baseball in Minnesota,” The National Pastime: Baseball in the North Star State (SABR 2012).

7. Bruce Berg and Reggie Aligada, Common Ground: McElroy Park’s Jack Brown Stadium (Jamestown, ND: Common Ground Press, 1996).

8. “Jamestown to Have All White Team this Year,” Jamestown Sun, April 9, 1931: 6.

9. “Jamestown to Have All White Team this Year.”

10. “Jamestown and Corwith Nighthawks Will Play Tie Off Here on Sunday,” Jamestown Sun, July 9, 1932: 6.

11. “Baseball Getting into Full Swing for Season’s Work.” General admission was 50¢ and grandstand seating 10¢.

12. Bruce, 130, citing the Kansas City Call, October 27, 1922.

13. “Jamestown Ball Club Getting Ready for Season’s Work,” Jamestown Sun, March 17, 1932: 6.

14. “Jamestown Baseball Club Will Open Season May 8,” Jamestown Sun, April 21, 1932: 6.

15. “Jamestown Baseball Club Will Open Season May 8.”

16. Bruce, 68.

17. A religious colony from Michigan which sponsored a talented, bearded, traveling team.

18. Bruce, 84. Plans failed due to stadium lease problems.

19. Dixon, 157-8.

20. Dixon, 160.

21. Thomas Merrick, “June 20, 1931: Old Pete brings night baseball to Jamestown,” SABR Games Project, Society for American Baseball Research, https://sabr.org/gamesproj/game/june-20-1931-old-pete-brings-nightbaseball-to-jamestown.

22. “Jamestown Club Plays Good Ball to Beat Visitors,” Jamestown Sun, May 31, 1932: 5.

23. Dixon, 161.

24. “Jamestown Took Both Games in Series From Duluth Team: Northern Pacific on Sunday,” Jamestown Sun, July 30, 1932: 6.

25. Dixon, 163.

26. Dixon, 163.

27. Gallivan pitched in the minors for Montgomery (Southeastern League) and Indianapolis (American Association) from 1935-38. His older brother Phil Gallivan was pitching with the Chicago White Sox in 1932.

28. “Monarchs Put Up Very Fine Ball Exhibition,” Jamestown Sun, August 2, 1932: 6.

29. “Team Defeated Only 7 Times in 1932 Season,” Jamestown Sun, August 15, 1932: 6.

30. Bruce, 78.

31. “Jamestown Puts Up Fine Game Here Tuesday,” Jamestown Sun, October 5, 1932: 6.

32. “Jamestown Puts Up Fine Game Here Tuesday.”

33. Dixon, 164.