John McGraw Comes to New York: The 1902 Giants

This article was written by Clifford Blau

This article was published in SABR 50 at 50

This article was originally published in SABR’s Baseball Research Journal, Vol. 31 (2002).

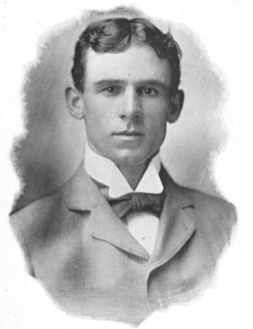

John McGraw was one of the most successful baseball managers ever, leading the New York Giants to ten pennants in his 30 years with the club. His arrival in mid-1902 marked the turning point in the fortunes of the Giants, a team which had been struggling for years. However, despite an influx of new players whom McGraw brought with him to New York, the Giants barely showed any improvement for the balance of the 1902 season, losing over 60 percent of their decisions in that period. This article will review the Giants’ 1902 season and attempt to show why McGraw was unable to make an immediate improvement in the team.

John McGraw was one of the most successful baseball managers ever, leading the New York Giants to ten pennants in his 30 years with the club. His arrival in mid-1902 marked the turning point in the fortunes of the Giants, a team which had been struggling for years. However, despite an influx of new players whom McGraw brought with him to New York, the Giants barely showed any improvement for the balance of the 1902 season, losing over 60 percent of their decisions in that period. This article will review the Giants’ 1902 season and attempt to show why McGraw was unable to make an immediate improvement in the team.

1902 was a season of turmoil not just for the Giants, but for all of Organized Baseball. The National League was at war not only with the American League, but with itself. In its December 1901 meeting, four owners supported a plan proposed by John Brush to convert the National League into a trust which would be owned by all eight owners. This trust would own all eight teams and the contracts of all players. The other four owners supported the candidacy of former league president Albert Goodwill Spalding. Spalding had led the league in its successful battles with the Player’s League in 1890 and the American Association in 1891, and these four owners felt he was the perfect choice to defend the league against the upstart American League.

The two sides couldn’t reach an agreement, and the trust group, including Giants owner Andrew Freedman, left the meeting. The other four owners, claiming a quorum was still present, elected Spalding president. A lawsuit was filed by the trust group and the matter wasn’t resolved until the beginning of April 1902. The season schedule was adopted on April 5, just twelve days before opening day.

The American League, under its strong president, Ban Johnson, had moved into several large Eastern cities in 1901 and declared itself a major league on a par with the NL. While its playing talent was probably not on a par with the NL’s that year, it did succeed in attracting such top stars as Nap Lajoie and Cy Young. Following the 1901 season, the AL took advantage of the chaotic situation in the NL to step up its player raids. Many of the NL’s top players such as Elmer Flick, Jimmy Sheckard, Jesse Burkett, Al Orth, and Ed Delahanty signed with the American League.

Meanwhile, the Giants seemed to be making little effort to resign their players or obtain new talent. By the end of 1901, regulars Kip Selbach, Jack Warner, Charley Hickman, and pitcher Luther Taylor, who had led the league’s pitchers in games started, had signed with American League teams. Most damaging, future Hall of Fame shortstop George Davis, the Giants’ manager in 1901, signed with the Chicago White Stockings. Later, third baseman Sammy Strang jumped ship as well.

The decline of the Giants since they were purchased by the petulant, domineering Andrew Freedman in 1894 seemed to be complete. Once one of the league’s premier franchises, the team had finished last or next to last the past three seasons. Freedman likely expected the trust scheme to be adopted, and that the Giants would get first pick of the league’s stars. Because of the stalemate over that issue, they had to rebuild the club the old-fashioned way. With no National Agreement between the major and minor leagues, there was no draft to provide a cheap source of new talent.

Late in December, the Giants started putting together a team for 1902 by signing minor-league pitchers Roy Evans and John Burke as well as catcher Manley Thurston. They also purchased second baseman/manager George Smith from the Eastern League champion Rochester team. An offer was made to Jesse Burkett, who had just jumped to the AL, but he turned it down. The Giants also tried to woo manager Ned Hanlon away from their crosstown rivals, the Brooklyn Superbas, but that was also unsuccessful. Towards the end of January, Freedman chose Horace Fogel to manage the team.

Fogel’s managerial experience consisted of one season at the helm of Indianapolis of the National League. Otherwise, he made his living as a sportswriter and editor, mainly in Philadelphia. Fogel promised to sign some stars, but all he found were college players, American League rejects, and “Roaring” Bill Kennedy, a one-time star pitcher who had been cut loose by the Superbas. As February neared its end, however, the Giants seized an opportunity when Chicago released first baseman Jack Doyle. Fogel quickly signed Doyle and appointed him team captain, giving him responsibility for the team during games. Doyle had been a member of the champion Baltimore Orioles in 1896 and had spent three seasons with the Giants before 1901. He was a good hitter and aggressive baserunner. However, he tended to make enemies wherever he went, as he was demanding and lacking in diplomacy.

The Giants didn’t go south for spring training, which was not unusual at the time. Fourteen players reported to the Polo Grounds on March 24 to begin working out under the direction of Jack Doyle. More arrived the next few days. As practice began, the team lined up this way: Captain Doyle at first, Smith at second, Walter Anderson at short, Billy Lauder at third, and Frank Bowerman behind the plate backed up by George Yeager. Veteran George Van Haltren would be the center fielder, with several players competing for the other two outfield spots, including Jim Jackson, Roy Clark, Libe Washburn, Jim Stafford, Jimmy Jones, and Jim Delahanty.

The pitching staff was led by the sensation of 1901, Christy Mathewson. Virtually every other pitcher from the prior year was gone. Attempting to replace them were Henry Thielmann (also an outfield prospect), Frank Dupee, Tully Sparks, Burke, Evans, Kennedy, and Bill Magee. Efforts were made to improve the team during spring training; on March 26, it was reported that the manager job was offered to Ed Barrow, then manager of the Toronto team in the Eastern League, and later Red Sox manager and Yankees president. Contracts were supposedly offered to American Leaguers Nap Lajoie, Elmer Flick, Topsy Hartsel, and others, and an unsuccessful attempt was made to purchase shortstop Wid Conroy from the champion Pittsburgh Pirates.

Anderson proved inadequate at short, and after Delahanty and Thielmann were tried there, the Giants signed Jack Dunn, who had been released by the Orioles. The weather was cold and rainy throughout spring training. Only 6 exhibition games were played, against college and minor league teams, with the Giants managing to win them all. Five other games were cancelled due to the weather. When that happened, the Giants could work out with weights or exercise machines in the Polo Grounds clubhouse.

Other players failing to make the grade during spring training were Stafford and Dupee, with Clark returning to complete his studies at Brown University. Bowerman and Van Haltren were injured during training camp; thus when the Giants opened the season at home against the Philadelphia Phillies on April 17, the lineup looked like this:

- Dunn SS

- Delahanty RF

- Jones CF

- Lauder 3B

- Doyle 1B

- Jackson LF

- Smith 2B

- Yeager C

- Mathewson P

Jack Dunn began his major-league career in 1897 as a pitcher. He converted to infield in 1901, playing third base and shortstop for the American League Baltimore Orioles. After his release by that team, he was signed by the Giants to fill their gap at short. He ended the season as a utility player, filling in at second and third and playing more games in right field than anyone else. He even started two games as pitcher, and relieved in another. Dunn spent two more seasons with the Giants as a utility infielder. He is best known today as the owner of the minor-league Baltimore Orioles, where he discovered and developed many players, such as Babe Ruth and Lefty Grove.

Jim Delahanty, one of five brothers to play in the major leagues, was a very good hitter who changed teams frequently during his 11-season AL and NL career, most of which was spent as a second baseman. He had spent the bulk of 1901 playing in the Eastern League. After spring training trials at shortstop and center field, he opened the season as the regular right fielder. This was his second major-league trial; his career would begin in earnest in 1904 as the regular third baseman for the Beaneaters.

Jim Jones was a fast runner without much hitting ability. Like Dunn, he had begun his career as a pitcher; Jones had played a few games for the Giants in 1901. 1902 would be his final major-league season. He was filling in for the veteran George Van Haltren, who was expected to be the Giants’ regular center fielder in 1902, as he had been since 1894. Van Haltren was nursing a cold and an injured finger. At 36 years of age, he was one of the oldest players in the league, and was frequently referred to in print as “Rip” Van Haltren. 1902 would be his 16th major-league season.

Billy Lauder was a good field, no hit third baseman. According to Ned Hanlon, Lauder was as good a third baseman as had ever played the game. Unfortunately, he had been out of professional baseball for two years, and was never able to regain his hitting eye.

Jim Jackson was a speedster who spent his rookie season in 1901 with the Baltimore Orioles. He had a .291 on base average and a .330 slugging average in 1901. Joining the Giants in 1902, where he had to deal with the foul strike rule, his hitting took a predictable fall. In addition, his fielding average fell from a league-leading .971 in 1901 to .897 in 1902.

George “Heinie” Smith was a slick-fielding, weak-hitting second baseman. Smith played for Rochester in the International League in 1901. At 30 years old, this was Smith’s first year as a regular in the majors after four previous trials. He would soon be regarded as the best defensive second baseman on the Giants since John M. Ward in 1893-94, but his big-league career would end the following year with Detroit. Smith and Lauder were the only Giants to play over 109 games in 1902.

George Yeager was a veteran of five big-league seasons as a backup catcher. 1902 would be his last year in the major leagues. He was filling in for the injured Bowerman.

After a band concert which concluded with “The Star-Spangled Banner,” and the first ball was thrown out by a former fire commissioner, the Giants got their season off to a rousing start with a seven to nothing victory. Over the next few days, they would lose more than they won before rattling off a seven-game winning streak to close their home stand.

As they headed for Chicago, the Giants had a 10-5 record. Their winning streak ended abruptly as Chicago swept the three-game series. However, the first two games were later disallowed by the league as Fogel had discovered before game three that the pitching rubber at West Side Park was two feet too close to home. (Those games were later replayed, with the Giants winning both.) Not including the two protested games, the Giants won four of the first six games on the trip.

On May 16 in Cincinnati, as the new Palace of the Fans was dedicated, George Yeager pinch-hit a two-run single in the ninth to cap a five-run rally and give New York a 14-7 mark. They looked like a pennant contender. However, the good times were over, as the team would lose 43 of its next 51 decisions. A few days after the Giants’ come-from-behind victory, Fogel was quoted in a Cincinnati newspaper making disparaging remarks about golden boy Christy Mathewson. He made a quick retraction, but his days at the helm of the Giants were numbered.

Personnel changes were coming fast and furious. Taylor jumped back to the Giants. Bill Magee was released after lasting only two innings in his first start. Delahanty was dropped after seven games. Steve Brodie, a veteran center fielder and former Orioles teammate of Doyle, was signed, released, signed again, released again, and finally signed for a third time the next day after an injury to the Giants’ latest outfielder.

Indeed, injuries and illnesses would plague the team all season, especially amongst the outfielders. Brodie, despite his multiple comings and goings, was the only person to play more than 67 games in the outfield for New York. The most severe injury occurred on May 22, when Van Haltren broke his leg sliding in Pittsburgh. He missed the remainder of the season, and his major-league career ended the following year.

A shortstop, Joe Bean, who had played with Smith at Rochester in 1901, was signed. Unfortunately, Rochester had an option on his services for 1902 and they got a court injunction against the Giants. This matter was resolved in a few days, with the Giants purchasing Bean’s contract.

Thielman, who was used in the outfield for a trio of games as well as on the mound, was dropped in mid-May as was catcher Thurston, who never got into a game. Outfielders came and went after two or three games. Pitcher Bob Blewett from Georgetown University was given a chance, but he lived up to his name, going 0-2 in five games. Libe Washburn, star pitcher at Brown University, was used in the outfield for a few games but never got a chance on the mound. Roy Clark had rejoined the team, but, like Mathewson and Sparks, didn’t play on Sundays. (This was a problem only when the team was playing in three western cities, since Sunday ball was illegal in the four eastern cities and Pittsburgh.)

After losing fourteen of their last 15 games in May, and rumors of dissension spread, changes were made. On June 2, Jack Doyle was stripped of his captaincy, with George Smith taking over that role. The next day, Fogel left the team due to his father’s death, and he never returned to the helm, with Smith being promoted to manager on June 11. In an effort to end the dissension on the club, Doyle was released late in June. These changes didn’t help the team, as they could only achieve a 5-27 record under Smith.

There had been rumors during the winter about Mathewson having a sore arm. Although he claimed to be fine during spring training and his first pitching appearances were successful, his performance soon fell off. This led to Fogel’s threat to bench him. Due to Matty’s sore arm and the Giants’ infield problems, Smith used him at first base for three games. There was some discussion about converting him to shortstop once his arm healed. While Matty was an excellent fielder on the mound and a good hitter for a pitcher, he proved a flop at first base, making four errors in his three games there, and he returned to pitching.

Meanwhile, on July 1, a new shortstop, Heinie Wagner, joined the team. He had been found playing sandlot ball in New York by Horace Fogel. No one on the team knew anything about him, and some fans thought the Giants had somehow obtained Pittsburgh’s star, Hans Wagner. Alas, Heinie, although later a capable major-league player, was not only not Hans, but also wasn’t ready for this level of play.

Another newspaper interview in early July gave insight into the Giants’ troubles. Jack Hendricks, who had been released after a brief trial in June in right field, spoke candidly to a Chicago Journal writer. He claimed that Bowerman and Yeager did all they could to prevent young players from succeeding and that the team had deliberately played poorly behind Blewett to make him look bad. Hendricks, a Northwestern University graduate who would go on to a long career as a manager in the National League and the minors, also had harsh words for Mathewson, calling him a “conceited pinhead” who constantly moaned when things didn’t go his way. Matty’s teammates rarely spoke to him, and gave him poor support also, according to Hendricks. On the other hand, he had nothing but praise for Doyle, who he said was very helpful to the young players and was a “splendid fellow.” He concluded that Freedman should make certain changes in the team, including the manager.1

In the meantime, over in the American League, the Orioles’ manager John McGraw was having his own problems. McGraw, another veteran of the NL Orioles of the 1890’s, had begun his managerial career with that club in 1899. He quickly established a reputation as a genius by leading the team to a strong fourth-place finish even though most of the club’s stars had been transferred to its sister team, the Superbas. When the American League moved into the east, McGraw was offered part-ownership of the Baltimore franchise. However, Ban Johnson insisted on supporting his umpires, which put him at frequent loggerheads with McGraw, a notorious ump-baiter. By mid-1902, McGraw was fed up with the frequent suspensions and fines handed him by Johnson. As a player, he had been out of action since being spiked by a baserunner on May 24.

On July 2, McGraw was spotted at the Polo Grounds, and rumors quickly spread that he would take over the helm of the Giants. On the ninth, it became official. The Giants signed McGraw to a three-year contract at $10,000 or $11,000 per year, a munificent sum for the time, when the top player salaries were $6,000-7,000 at best. In his first interview as the Giants’ pilot, McGraw stated that he had been given unlimited authority to improve the team. “The only instructions that I have received,” he stated, “were to put a winning organization in this city at any cost.”2 Although he admitted that first place was out of reach this year, he did expect the team to finish in the first division and then compete for the flag in 1903.

The details of how McGraw left the Orioles, of which he was part-owner, and how he planned to strengthen the Giants, soon became public. He had arranged for a majority of the Orioles’ stock to be sold to Andrew Freedman, who released McGraw and many of the team’s stars, including future Hall-of-Famers Joe McGinnity and Roger Bresnahan, as well as first baseman Dan McGann and pitcher Jack Cronin.3 This quartet joined McGraw and the Giants for his first game as manager on July 19. At the same time, Joe Kelley, who had also played on the Orioles of the 1890’s, signed with John T. Brush to be Cincinnati’s playing manager; joining him was center fielder Cy Seymour. In the ten days between McGraw being announced as new manager and his first game, he was supposedly trying to sign new players, but was in fact being treated for appendicitis, which would plague him for the rest of the season.

McGraw released seven players upon joining the Giants: Yeager, O’Hagen, Blewett, Wagner, Burke, Sparks, and Evans. Roy Clark received his 10-day notice of release two days before McGraw’s signing. In addition to the four Baltimore players, the Giants soon added left fielder George Browne, who had been released by the Phillies, and pitcher Roscoe Miller, who jumped from the Detroit Tigers. Libe Washburn was released on July 25 and Jimmy Jones was suspended and then released after assaulting umpire Bob Emslie on August 6. Bresnahan split time between right field and catcher, while Browne became the regular left fielder. Both were big improvements over the players the Giants had previously tried. McGraw became the new shortstop.

While the Giants lost their first game under McGraw, the team reportedly showed more “life” than they had in some time. After two days off and an exhibition game versus the Orange (New Jersey) Athletic Club, they took three out of five games against the Superbas. However, despite strong performances from some of the newcomers, the team kept on struggling, and finished the season in last place.

Injuries continued to plague the Giants, and one led to a challenge to McGraw’s authority. Frank Bowerman’s foot was hurt by a foul ball on August 2. The next day the team played an exhibition game in Bayonne, New Jersey and Bowerman didn’t suit up. In fact, due to injuries on the Bayonne club, Roger Bresnahan caught all nine innings for both teams. Since Bowerman hadn’t asked permission to sit out, McGraw fined him 50 dollars. Bowerman argued that the fine wasn’t fair, and he refused to suit up again until it was rescinded. He threatened to jump to the American League but gave in and was back in uniform on August 7. In his first game behind the plate after the incident, however, he committed three errors and five passed balls. While it is not known if his poor fielding was deliberate, it so disgusted Mathewson that in the ninth inning, after the final two passed balls, Christy began lobbing the ball over the plate, and a 3-2 deficit quickly became an 8-2 loss. Despite all this, and later rumors of signing with the St. Louis Browns, Bowerman remained with the team through the 1907 season.

John T. Brush sold most of his stock in the Reds in August, and a few days later was made managing director of the Giants. He worked with McGraw in trying to obtain new players. Late in the season, with McGraw aiding in the negotiations, he bought Freedman’s stock and became president of the board of directors. A new era in Giants’ baseball was beginning.

Why didn’t McGraw turn around the Giants’ fortunes in 1902 despite the influx of new talent? The reason seems to be lack of interest. Apparently, he decided soon after arriving in New York that the Giants wouldn’t be able to reach the first division and turned his attention to obtaining players for 1903. In this he was successful; he signed several American Leaguers and the team rallied to second place that year. However, this meant that McGraw was away from the team for long stretches. In all, he missed 20 games due to scouting trips and his appendicitis. The team’s record in these games was 8-12, little different from their overall mark after McGraw became manager. As further evidence that McGraw wasn’t his usual fighting self, he wasn’t ejected from a single game by the umpires with the Giants in 1902. He had promised to contain his temper after coming to New York, and did so. A year later, he was quoted as saying “Baseball is only fun for me when I’m out front and winning. I don’t give a hill of beans for the rest of the game.”4

The Giants continued to be disrupted by injuries as well as rainouts; seven games were postponed between September 9 and October 1. Also, McGraw began the transition from player-manager to bench-manager; 1902 was his last season as a regular player, and he played his last game of the season on September 11. This probably took some getting used to for McGraw.

McGraw made one serious personnel misjudgment, releasing Tully Sparks and signing Roscoe Miller. Miller went just one and eight with a 4.58 ERA. The following season he won two and lost five with a 4.13 ERA. Meanwhile, Sparks was in the midst of a 12-year major-league career which saw him credited with 121 pitching wins and an ERA of 2.79.

The result of the above was that the Giants record under McGraw was just 25-38-2, although 41 of the games were played at home, and they gained only a 1/2 game on seventh place. By contrast, the Cincinnati Reds after hiring Joe Kelley as manager were 36-26, climbing from seventh to fourth.

OF injuries:

4/17 Van Haltren out with cold and infected thumb until 4/19

4/18 Jones hurt sliding / didn’t play again until 5/12

4/22 Jackson out with tonsillitis / back 4/25

5/22 Van Haltren broke leg / out remainder of season

5/28 Jones hurt when Long fell on him / back 6/2

6/2 Clark’s finger injured-played 6/4 but next day thumb operated on, next played 7/2

6/6 O’Hagen hit by batted ball / back 6/20

6/17 Washburn hit by pitch, broken nose / out until 7/19

8/29 Bresnahan in bed with illness / back 9/8

1902 Giants transactions

|

Date |

Transaction |

|

04/25 |

Released Magee |

|

04/28 |

Signed Joe Bean |

|

04/29 |

Released Jim Delahanty |

|

05/05 |

Purchased Joe Bean from Rochester |

|

05/08 |

Luther Taylor rejoined team (had signed over winter but jumped to AL) |

|

05/14 |

Steve Brodie released |

|

05/20 |

Released Henry Thielman and Thurston |

|

05/24 |

Signed Tom Campbell? |

|

05/29 |

Acquired Hess, Hartley |

|

05/30 |

Signed Libe Washburn |

|

06/01 |

Signed McDonald |

|

06/03 |

Signed O’Hagen |

|

06/04 |

McDonald retired, Jackson released |

|

06/05 |

Hartley retired |

|

06/07 |

Signed Steve Brodie, Nichols, Hendricks |

|

06/14 |

Signed Blewett |

|

06/17 |

Released Steve Brodie |

|

06/18 |

Signed Steve Brodie |

|

06/19 |

John Hendricks given notice of release |

|

06/20 |

Jack Doyle released (6/19?) |

|

06/26 |

Joe Bean given notice of release (6/25?) |

|

07/01 |

Signed Heinie Wagner |

|

07/08 |

Roy Clark given notice of release, signed John McGraw |

|

07/15 |

Released Blewett and Clark |

|

07/17 |

Released O’Hagen, Burke, Yeager, Sparks, Evans, Wagner; signed Bresnahan, Cronin, McGann, McGinnity. |

|

07/21 |

Signed George Browne, R. Miller |

|

07/25 |

Released Libe Washburn |

|

08/01 |

Signed Joe Wall |

|

08/06 |

Jim Jones suspended for balance of season |

|

09/01 |

Borrowed Jack Robinson from Bridgeport |

Sources

The main sources used for this article were the New York Telegram and the Sporting Life. Other newspapers consulted were the New York Times, New York Herald, New York Evening World, New York Press, and The Sporting News. In addition, the following books and other records were used:

Charles Alexander, John McGraw

Joe Durso, Days of Mr. McGraw

Blanche McGraw with Arthur Mann, The Real McGraw

John Thorn and Pete Palmer. eds., Total Baseball, 3rd edition

Craig Carter, ed.. The Sporting News Complete Baseball Record Book, 1994 edition

1902 Official National League Statistics

Information Concepts Inc. records of 1902 season

Thanks to Cappy Gagnon, John Pardon, David W. Smith, Darryl Brock, and Bill Deane for sharing their research, and to Paul Wendt, Frank Vaccaro, and Skip McAfee for their help with this article.

Notes

1 Chicago Journal as reprinted in Sporting Life, July 12, 1902.

2 New York Herald, July 10, 1902.

3 Details of the story vary, with some sources claiming that McGraw had reached agreement with Freedman by mid-June, with team secretary Fred Knowles and possibly John Brush acting as go-betweens. Mrs. McGraw, in her biography of her husband, claimed that the jump to New York was part of a plan between McGraw, Freedman, Brush, and Ban Johnson to put an AL team in New York, but she offers no evidence to support this notion.

4 David H. Nathan, ed., Baseball Quotations (New York: Ballantine Books, 1991).