Johnny Pesky, On Signing with the Red Sox

This article was written by Bill Nowlin

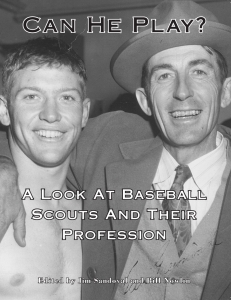

This article was published in Can He Play? A Look at Baseball Scouts and Their Profession (2011)

Stripped to the waist, Johnny was working as groundskeeper one day at the ballpark in Silverton, Oregon, when a well-dressed gentleman approached him. Louis Butler represented one of the St. Louis clubs and he was sporting a shirt and tie. Johnny had just finished watering and dragging the field. “I was marking the field, getting ready for the game, then I was going to go home and get something to eat, so I’d be ready to play the second game,” Johnny recalled. “This was about 4:30 in the afternoon. He says, ‘Is Silverton playing tonight?’ I say, ‘Yes, they’re playing the second game.’ He says, ‘Do you play?’ I said, ‘Yeah.’ He says, ‘What?’ and I says, ‘Shortstop.’ He asked me what my name was. He says, ‘Jesus, I’m supposed to see you, kid. I haven’t seen you play.” That night I got three hits.

Stripped to the waist, Johnny was working as groundskeeper one day at the ballpark in Silverton, Oregon, when a well-dressed gentleman approached him. Louis Butler represented one of the St. Louis clubs and he was sporting a shirt and tie. Johnny had just finished watering and dragging the field. “I was marking the field, getting ready for the game, then I was going to go home and get something to eat, so I’d be ready to play the second game,” Johnny recalled. “This was about 4:30 in the afternoon. He says, ‘Is Silverton playing tonight?’ I say, ‘Yes, they’re playing the second game.’ He says, ‘Do you play?’ I said, ‘Yeah.’ He says, ‘What?’ and I says, ‘Shortstop.’ He asked me what my name was. He says, ‘Jesus, I’m supposed to see you, kid. I haven’t seen you play.” That night I got three hits.

“A day later, we’ve got to play again and he comes back. ‘I want to see you one more time,’ he said. I had another good night. In fact, I led the tournament in hitting and I got a couple of trophies, one as an infielder and one for the batting championship. He said, ‘I liked what I saw, kid. I’d like to sign you’ and he made an offer of money. He threw twenty-five hundred dollars at me. Jesus. I never saw that kind of money; we’d be lucky if we had five bucks to spend. When the tournament was over, I went home and told my little brother we had a chance to get a few bucks here. My folks sure could have used it.”

One Detroit Tigers scout recalled how they would even follow Johnny to the ice rink. “We used to sit around those ice joints with our teeth chattering,” he moaned. It was Ernie Johnson’s manner and personality that won the day for the Red Sox, even though the offer he conveyed was not at all the best financially. Johnson lived in Santa Monica, California, and had the entire West Coast as his territory for the Red Sox. Johnson was a former major leaguer, with a ten-year career for the White Sox, the Terriers, the Browns, and the Yankees, spanning the years from 1912 to 1925. He’d been scouting for over a decade when he found Johnny. The home office was convinced not just by Johnson, but also by the “constant suggesting” of Red Sox pitcher Jack Wilson, a Portland native who had seen Johnny play. Wilson had apparently bent Red Sox manager Joe Cronin’s ear on the subject as well.

Ernie Johnson wisely cultivated the Paveskovich family as well as the prospect. In this case, it paid off – and saved the Red Sox some money. Johnny remembered Johnson’s approach. ”He would come into the house. We didn’t have the best house, but it was always clean. He would bring my mother these beautiful flowers. He’d bring my father a bottle of I.W. Harper, that nice bourbon in those days. My father liked to nip a little bit. He’d savor that for about two months.

“I had another club that was going to give me more money, but Johnson got to know my parents. Either my oldest brother or my oldest sister would be there to interpret for them. They had a language barrier. He used to watch our games and kind of latched on to me, you know, being a middle infielder. He liked what I did.

“Johnson and the Red Sox hadn’t said anything yet, just an overture of some five hundred dollars. Butler came and he talked to my parents. My mother just shook her head. She said, ‘No. I don’t care about the money. Mr. Johnson is the one we’re going to deal with.’ My mother said to me, ‘Mr. Johnson, he was very nice to us. You stay with Mr. Johnson and Boston.’

“Cy Slapnicka from Cleveland was a scout out there. He came in, too, but Johnson came in two or three times and he always went in the kitchen and had coffee with them while I was at school. He looked around; he knew everything was nice and clean. My mother liked this guy. We had this other offer, but anyway, my mother said, ‘No, Johnny. Boston. Mr. Johnson, Johnny. Nobody else. He take care of you, Johnny.’”

When Johnny’s brother Vince talks about it, one gets the sense the family held to other priorities than the dollar. “We didn’t have much when we grew up. Today we can count our blessings that we did have parents who provided three meals a day. A good home life and all that goes with it – the love and affection. Really, even today that’s still the hallmark of perfection – kids that have loving parents and a good home. This is what we all live for: to have a better life in the future. I think we did well.”

Johnson never upped his offer. ”We got the five hundred, but if we stayed in the organization – I was supposed to stay for two years – they’d give me a thousand dollar bonus. After the first year, they gave me the thousand dollars. So really fifteen hundred is what I got. Still a thousand less than the other club. The money could have done a lot for my family but mom said no. My brother and my two older sisters were working; they were bringing money home. They were maybe getting twenty dollars a week, maybe twenty-five dollars a week. That’s in the late ’30s, early ’40s. My mother she said, ‘No. Mr. Johnson, he take care of you, Johnny.’

“No one had money in those days. So that’s how it turned out. That’s why I signed with the Red Sox, and it was the best thing that could have happened. I signed with the Red Sox and I’m glad I did. It turned out pretty good.” Marija Paveskovich’s instincts were correct. The Red Sox did take good care of Johnny. And vice versa.

Johnson’s homey approach carried the day, even when at least one other scout offered five times as much upfront money. These were still Depression times and to turn down a full $2,500 to sign with the Red Sox for just $500 was a bold decision for the family to make.

As Johnny finished his first year with the big-league club and was about to head into the Navy for who knows how long during the Second World War, Red Sox owner Tom Yawkey had a treat for the rookie. In the process, he earned himself and the ballclub a loyal friend for life. “The last week of the season in ’42,” Johnny tells, “There was a note on my chair to go up and see Eddie Collins. Of course, we were never allowed upstairs. Ted [Williams] sees this thing and he says, ‘What’s that?’ I said ‘I gotta go up and see Mr. Collins.’ ‘Well, hurry up.’ So, I went upstairs. He called me in his office and said, ‘Sit down.’ So, I sat down, and he says, ‘Well, you had a fine year, Johnny. You played well and you weren’t any problem off the field for us.’ There wasn’t much of that off-the-field activity in the years we played; you couldn’t afford it. Well anyway, he handed me this envelope. So now Ted is waiting for me in the clubhouse. ‘What the hell happened?’ ‘Well, he called me in and gave me this envelope.’ So, he says, ‘What the hell’s in it?’ So, I opened it up and there was a check there for five thousand dollars.”

Johnny had been sending money home, as it was, but now he was able to take the bonus – an amount in excess of his entire $4,000 salary – and pay off the new house on Overton Street, a house his brother Vince still lives in today. “That money paid for the house. I think the house cost about $4,800.

“It has stayed with me, what Mr. Yawkey did. That’s why I have always loved the Red Sox – with Mr. Yawkey – because of what he did not only for me but for my family. They were so darn nice.”

This article is adapted from Mr. Red Sox: The Johnny Pesky Story, by Bill Nowlin (Cambridge Massachusetts: Rounder Books, 2004).