Labatt Park’s Longevity Claim

This article was written by Riley Nowokowski - Robert K. Barney

This article was published in Our Game, Too: Influential Figures and Milestones in Canadian Baseball (2022)

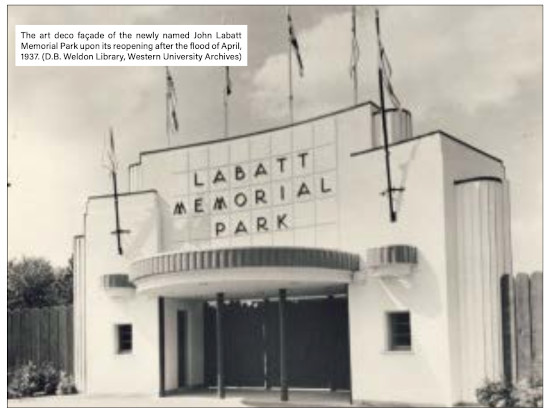

The art deco façade of the newly named John Labatt Memorial Park upon its reopening after the flood of April 1937. (D.B. Weldon Library, Western University Archives)

There has been but one serious challenge mustered against Labatt Park’s distinction: “baseball history’s oldest continuously operating ball grounds.” That challenger is Fuller Field in the town of Clinton, Massachusetts.

Clinton, nestled in bucolic surroundings some 40 miles west of Boston, nevertheless suffers from a long-embedded “tiredness.” It was a bustling nineteenth-century town of world fame, but much of its present business landscape renders the impression of being in recession. Many of the town’s streets and sidewalks are in disrepair. Though a fatigue-like mist appears to envelop today’s Clinton, in its heyday in the nineteenth century, Clinton was a dynamic community, featuring some of America’s best-known manufacturing firms, most especially those linked to a booming textile industry. In fact, Clintonian Erastus B. Bigelow rose to become one of the world’s most important and best-known inventors/entrepreneurs with his invention and development of the power loom, including his subsequent scientific application of that loom to what we know today as the process by which screening for windows, doors, and porches is manufactured.

Then, too, Clinton was an enviable center of cultural flamboyance. Appearing in Clinton’s civic halls and private salons for over a half-century were many of America’s most celebrated writers, entertainers, cause-conscious lecturers, sports stars, even presidents of the United States, a legion of men and women that included such historical luminaries as Henry David Thoreau, Ralph Waldo Emerson, Frederick Douglass, Mark Twain, Carrie Nation, John L. Sullivan, Agnes Moorehead, and two Roosevelts, Franklin and Theodore.1

We are grateful to the librarians of the Bigelow Free Public Library in Clinton for providing us, during a research visit there in August 2018 with historical documents appropriate to Clinton’s challenge to the Labatt Park distinction. Baseball has been a fixture in Clinton for nearly as long as some of the earliest historical records of the sport in American culture can attest. One can certainly pinpoint an 1865 Clinton newspaper notice offered by one of the local baseball aggregations, the “We’ll Try Baseball Club,” inviting ladies and gentlemen to attend its annual “baseball-sponsored ball.” 2

A “darkened and dog-eared by age”3 four-by-five-foot oilcloth survey map of Clinton, dated 1878 and discovered by officials of the Clinton Historical Society in 2004, depicts a baseball infield diamond on property bounded by High and Allen Streets. Clinton’s argument proposes that the infield diamond presently in place on Fuller Field, a “multi-purpose” facility operated by the town’s Parks and Recreation authority, is situated in exactly the same place as the baseball diamond depicted on the 1878 “oilcloth survey map.” Researching into the antiquity of baseball parks and diamonds, local Clinton historian Bastarache found no other claim equal to or offering an older date of baseball diamond origin and continuous use, with the exception of that of Labatt Memorial Park in London, Ontario.

Upon inquiry to London’s Labatt Park historians,4 Bastarache learned that Tecumseh Park (the park’s original name), though predating Clinton’s 1878 “origin claim” by one year (1877), was devastated by a flood in April 1937, causing it to cease to function for an interim, not to reappear until 1938 as Labatt Memorial Park, and, in Bastarache’s incorrect conclusion, “moved” to a completely different location. To Bastarache, then, Labatt Park’s “continuous use” claim could not be defended after the season of 1936. But apparently unknown to Bastarache was the fact that Tecumseh Park/Labatt Park was never moved. In the wake of the devastating 1937 flood, Kensington Flats, including Tecumseh Park, was inundated, and the park’s playing surface and infrastructure severely damaged. Operations at the ball grounds ceased entirely. Over time, the flood waters receded; the Flats returned to normalcy. But the ground’s ball field and supporting infrastructure were ruined.

Nevertheless, the John Labatt Brewing Company purchased the former Kensington Tecumseh Park ball field land and promptly deeded it to the City of London in perpetuity. Further, the Labatt family gifted $10,000 to the city for the restoration of the baseball park in the identical spot of its origin. Tecumseh Park rose in all its original splendor, renamed Labatt Memorial Park. But Bastarache was on a mission. Hence, to Guinness World Records and the National Park Service, he proceeded to launch a quest to have Clinton’s Fuller Field ordained as the oldest continuously used baseball field in the world, dating to 1878. In fact, Bastarache went further, claiming that the Fuller Field baseball site “may actually date back to 1865 when baseball began in Clinton.”5 Had Bastarache consulted an 1876 Clinton map, he would have found that the Fuller Field baseball site was clearly not in place prior to 1878.

While Guinness certified Bastarache’s claim, and accordingly in its 2007 annual edition affirmed the authenticity of Fuller Field’s unique baseball antiquity, certification of the “Clinton distinction” failed in the halls of decision-making in the National Park Service’s National Registry of Historical Landmarks.6 We would suspect that the National Park Service’s Registry of Historical Landmarks remains decidedly more rigorous in its survey of “origin evidence,” to say nothing of the proof of “continuous use,” than does a commercial press such as Guinness. The silence from government authority, the custodian of historical landmark claims, is a deafening commentary on the legitimacy of Clinton’s assertion. On Guinness‘s website appears the following: “The claim (Clinton) is based on maps of the town that date as far back as 1878, and box scores from games played every year.”7 This is the only occasion where a reference to evidence of “continuous use” (“box scores”) is offered, but it is merely a reference, rather than evidence itself. If such evidence exists, Bastarache would surely have brought it forth to support the “continuous use” aspect of his argument. We believe no such evidence exists, but if it does indeed exist, has never been examined relative to the Clinton claim. Finally, disastrous to Clinton’s claim was the removal of Fuller Field from Guinness World Records, replaced in its 2009 edition by Labatt Memorial Park in London.8

ROBERT K. BARNEY, an American citizen, has lived and worked in Canada at Western University for 50 years. Educated at the University of New Mexico, he received his PhD in 1968; in 2014 Western University awarded him a doctor of laws, honoris causa. Recently he has worked with City of London heritage officials on a proposal to federal authorities for Labatt Memorial Park to be awarded National Heritage Site distinction.

RILEY NOWOKOWSKI is a PhD Candidate at Western University in London, Ontario. He loves all types of sport but takes a particular interest in baseball history. His work largely has focused on sport during the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries.

Notes

1 For more on this see A.J. Bastarache, An Extraordinary Town: How One of America’s Smallest Towns Shaped the World (Clinton, Massachusetts: Angus MacGregor Publishing, 2005).

2 See Bastarache’s chapter, “Making Sports History” (p. 95), in his An Extraordinary Town.

3 The phrase “darkened and dog-eared by age” is from Peter Schworm, “Fielding Dreams: A Central Massachusetts Town Hopes an 1878 Map Will Bring Visitors and Bragging Rights to a Spot in Baseball History,” Boston Globe, August 14, 2005: 29. The phrase may in fact have been spoken directly to Schworn by his interviewee, A.J. Bastarache.

4 In this case, Barry Wells, as told to the authors by Wells himself during a tour of Labatt Park on November 10, 2018.

5 Bastarache, 95.

6 For the earliest notation of the National Park Service Submission, and actual Guinness submission, see Schworm, “Fielding Dreams.”

7 https://www.waymarking.com/waymarks/wm5566_Worlds_Oldest_Baseball_Diamond_in_Continuous_Use_Fuller_Field_Clinton_MA.

8 Craig Glenday, ed., Guinness World Records 2009 (New York: Bantam Books, 2009), 191.