Lifting the Iron Curtain of Cuban Baseball

This article was written by Peter C. Bjarkman

This article was published in SABR 50 at 50

This article was originally published in SABR’s The National Pastime, No. 17 (1997).

For a tradition-minded American baseball fan fed up with ear-piercing Diamond Vision entertainment, cavorting cartoon-style mascots, shopping-mall stadia, luxury-box extravagance, inflated beer and parking prices, plastic-grass fields, and spoiled ballplayers, a trip around the Cuban ballpark circuit in mid-February — during the National Series championships comprising the Cuban postseason — seems a refreshing escape into baseball’s pristine past. In Havana and Pinar del Rio and Santiago de Cuba, the diamond action remains pure, the off-field distractions are minimal, and the game continues to thrive at its own beautiful pace and rhythm.

Havana’s 55,000-seat Estadio Latinoamericano is a genuine throwback. The park’s electronic center-field scoreboard features only lighted displays of lineups and line scores, and is entirely void of video displays or between-inning commercials. The ballplayers’ uniforms are equally simple, recalling modern-day industrial league or softball uniforms in the States. The fans are focused on the game alone for nine innings (or less, since Cuban baseball features aluminum bats and an Olympic 10-run rule after seven innings) and they commune joyfully about baseball’s timeless rhythms. In a nation of severe material shortages and limited personal freedoms, baseball is a welcome panacea.

Of course, there are stark differences from old-time North American baseball, as well. The outfield wall decorations urge spectators to remain loyal to the Castro revolution. A nationwide paper shortage means no printed scorecards and souvenir stands, and beer vendors are unheard of. Team rosters represent geographical regions, and players are therefore never traded among teams. And a sight entirely foreign to North American ballparks — glowing electric-light foul poles — reminds the visitor that this is not Brooklyn or the Bronx or Philadelphia.

Problems

For Cuban fans, however, the 1997 winter playoffs hardly represented a throwback to past glory days. Cuban baseball has changed drastically in recent seasons and most fans agree that this has been largely for the worse. Many of the nation’s top stars have defected to the majors or have, inexplicably, been forced to retire. The defectors — great young pitching prospects like Diamondbacks recruits Larry Rodriguez and Vladimir Nunez, and spectacular Mets shortstop Rey Ordonez — generate little ill-will among the fans and ballplayers left behind. But the forced retirements of perhaps Cuba’s best-ever shortstop, German Mesa, and one of its most popular sluggers, outfielder Victor Mesa, have left the fans feeling cheated.

The recent Series Nacional season and the following postseason playoffs were often played in half-empty stadiums, especially in Havana. Fans complain that the game is being gutted by the peddling of players to the Japanese Industrial League and to fledgling pro circuits in Italy, Nicaragua, Ecuador, and Colombia. Meanwhile officials of the Cuban League maintain their steadfast insistence that the nation’s emphasis remains on amateurism in baseball and on preparing for another Olympic triumph in Australia in the year 2000. One rumored cash deal for Omar Linares and Orestes Kindelan with the Japanese pro circuit was quickly nixed.

Yet veterans like Victor Mesa (reportedly headed to Japan’s Industrial League) and 1992 Olympic star hurler Lazaro Valle (bound for Italy) are being retired and sent overseas. Mesa was inexplicably sent packing while only a few homers short of breaking the all-time Cuban career record. German Mesa and exiled hurler Orlando “El Duque” Hernandez — brother of Marlins farmhand Livan Hernandez — were supposedly banned for dealing with a North American agent. (The agent, a Cuban-American with Venezuelan residency, is now serving a 20-year Cuban prison term for his part in the affair.)

Rumors persist that the forced retirements of the two Mesas and others mark an effort to clear space on the national team for young stars like Miguel Caldes, Eduardo Paret, and Jose Estrada, who might otherwise also consider the option of big-league defection.

The crisis has in part been brought on by changes in the economic structure of baseball abroad. Pro ball in the U.S. with its mega-level salaries is now a far greater lure than ever before for low-paid “amateurs” toiling with major-league skills in the talent-rich Cuban League. And Japan is becoming a magnet as well. The unconfirmed story about Linares and Kindelan and top Cuban pitcher Pedro Lazo reportedly involved a $10 million offer from the Japanese.

The Mesa messes

At the top of the list of retirees and suspensions stand German Mesa and Victor Mesa, unrelated stars of the past half-decade who are two of the finest players in recent Cuban history. The popular and muscular Victor Mesa, who toiled with Villa Clara during the past decade, is a lifetime .313 hitter and extraordinary basestealer, who also stands well up on the career homer list. German Mesa was the starting shortstop on the Cuban national team for six seasons before being dropped from the Olympic squad in favor of hot prospect Eduardo Paret. While Paret flashed his defensive brilliance for two weeks in Atlanta, and Rey Ordonez is already drawing legitimate big-league comparisons with Aparicio and Concepcion in New York, Cuban fans still swear that Mesa is the island’s best-ever shortstop.

Most recent defectors have been pitchers. Failures to dominate in the majors as they did in Cuba by Rene Arocha (an arm injury sidetracked his career after 11 wins for the Cardinals in 1993), Livan Hernandez (he labored at AAA Charlotte last season), and Oswaldo Fernandez (7-13 with the Giants in 1996), have raised questions about the true level of Cuban talent. Indeed, the aluminum bats used in the Cuban League spawn throwers, not pitchers. Cuban hurlers are also consistently overused at home as both starters and relievers.

Several new defectors may soon resurrect the Cuban reputation. Ariel Prieto is a top pitching prospect with Oakland despite his slow start in 1996 (6-7, 4.15 ERA). Larry Rodriguez may be even better than Prieto, and was given a $1.25 million signing bonus by Arizona. And Ordonez has caused a storm of excitement in only one season with the Mets. Ordonez is a useful yardstick, since he was far from the best Cuban shortstop at the time of his defection. The future Mets star had been buried behind German Mesa and Paret, who is the best all-around shortstop I have seen since Luis Aparicio. He runs with abandon (swiping 43 bases in this year’s short 65-game Cuban season), hits with power, and tracks down aluminum-bat liners with flawless precision. And Abdel Quintana, a hot 17-year-old prospect with the playoff-bound Industriales team, was recently rushed into the starting lineup in Havana and may soon be even better than either Mesa or Paret.

The old days

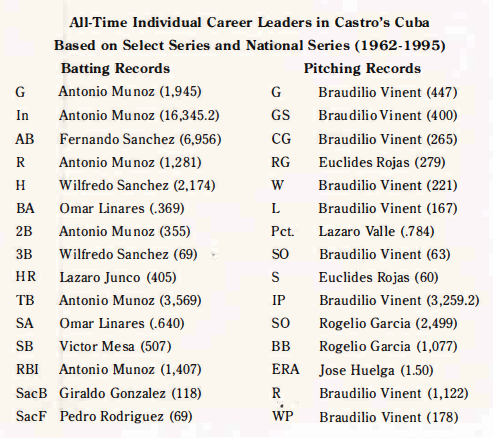

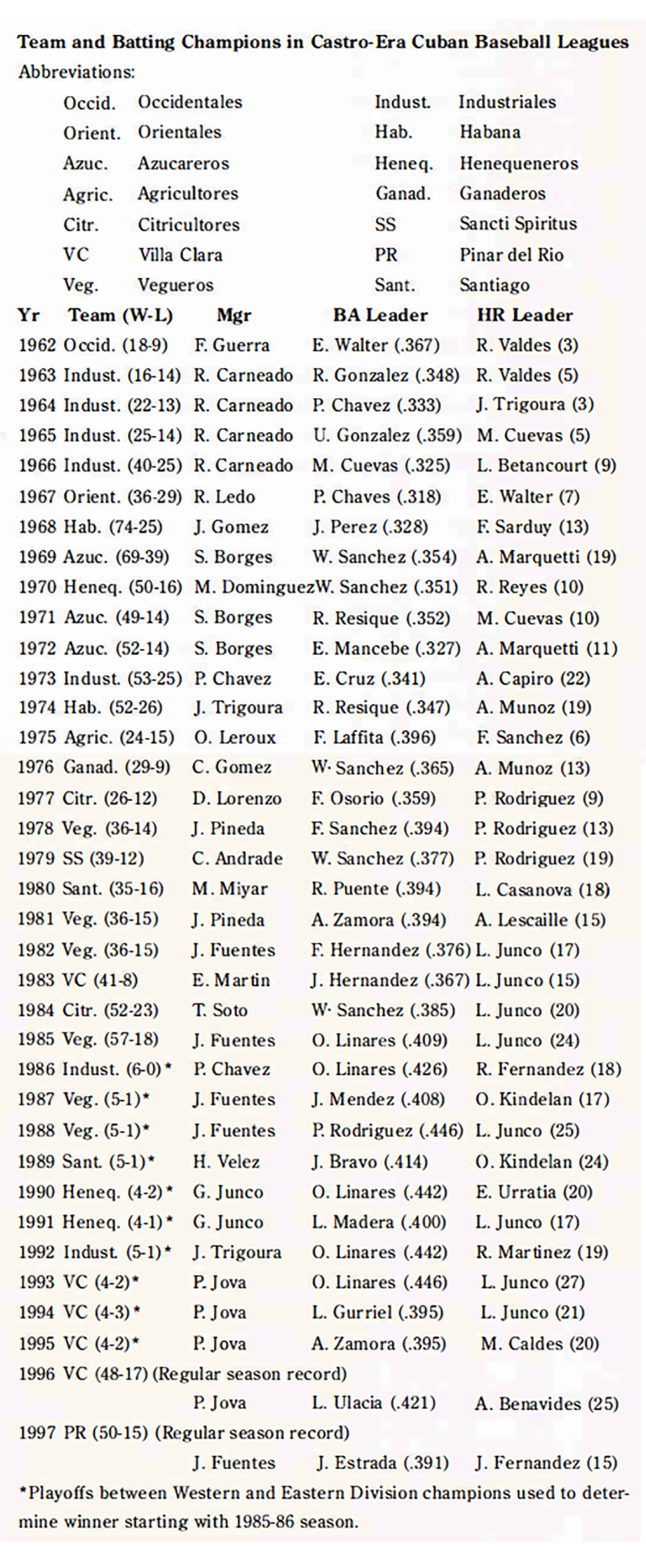

If the talent pool is thinning, this, like much else in Cuba these days, is a sharp departure from the heady years during the ’60s, ’70s, and early ’80s. For three decades, the Cubans maintained the world’s greatest showcase of amateur baseball talent. The ballparks in Havana, Holguin, Mantanzas and other cities were home to some of the greatest diamond stars that U.S. fans never saw. Heroes of this era included Wilfredo “El Hombre Hit” Sanchez, Luis Casanova, Fidel Linares (Omar’s father), Antonio Munoz, Manuel Alacron, Augustin Marquetti, and Braudilio Vinent. Lefty-swinging Wil Sanchez was one of the greatest hitters in Cuban history, winning no fewer than five batting titles, including the first back-to-back pair in 1969 and 1970. Today, his lifetime mark of .332 trails only those of Linares (.373), the league’s first-ever .400 hitter, and Alexander Ramos (.337), the latest Cuban to reach the 1,000-hit plateau.

In the ’80s the heavy hitting of Wilfredo Sanchez was replaced by that of Antonio Munoz (370 career homers), Lazaro Junco (the all-time home run leader), and finally Omar Linares. Linares has dominated the hitting of the ’90s (with three .400- plus seasons), along with slugger Orestes Kindelan (now only three short of Junco on the homer list with 402), fleet-footed leadoff specialist Luis Ulacia (last year’s batting champion), and a group of young stars paced by Jose Estrada and Miguel Caldas.

The pitching of the ’70s and ’80s was largely dominated by popular flame-throwing right-hander Vinent, considered the greatest Cuban hurler of the Castro era. Most of the lifetime pitching marks are still held by this superb hurler who won (221) and lost (167), more games than any Cuban moundsman, and in 1986 also became the first island hurler to reach the 2,000 career strikeout mark. He also still holds the marks for complete games and games started.

Cuba’s rich baseball history stretches back long before Castro and the 1959 revolution. The game was first played there two years before the birth of the National League. Cuban Steve Bellan became the first-ever Latin big leaguer, when he appeared with the National Association Troy Haymakers in 1871. Cubans also appeared in the National League before the First World War (Rafael Almeida and Armando Marsans with Cincinnati in 1911), and Dolf Luque was a legitimate star (27-8 with Cincinnati in 1923) long before major-league integration.

But it was the post-World War II period that saw a full-scale Cuban invasion of the majors — first with a handful of Washington Senators journeymen, then with flashy ’50s stars like Minnie Minoso, Camilo Pascual and Pete Ramos, and finally with Zoilo Versailles, Luis Tiant, Tony Oliva, and Tony Perez, who made their marks in the ’60s and ’70s.

Back home in Havana, the Cubans had been hosting top-flight winter league play between black and white Cubans and North Americans since the mid-’20s. They were also dominating the world amateur scene throughout the ’30s and ’40s, and the winter professional Caribbean World Series during its first phase from 1949 through 1960. Cuba won the first title in Havana in 1949 and seven of the first dozen competitions.

A top pro league in the ’40s and ’50s featured legendary teams representing Club Havana, Almendares, Cienfuegos and Marianao, and showcased a mixture of Cuban stars and major leaguers in the sparkling new El Cerro Stadium (today’s revamped and renamed Estadio Latinoamericano).

The Cuban Structure

After Castro’s takeover, the powers of Organized Baseball pulled the plug on the International League Havana Sugar Kings. (For interested readers the details of Cuban baseball history are laid out in my book Baseball with a Latin Beat published in 1994.) Castro’s reaction was to mandate a strictly amateur league and a yearly national series between regional teams that consisted of two short seasons and a championship playoff round. It is from this internal season that national teams have long been selected to represent Cuba in Olympic, World Cup, Pan American, and other international competitions. The result in recent decades has been a series of powerhouse Cuban teams that have posted an 80-1 international record between the 1987 Pan American Games in Indianapolis and the 1996 Olympics in Atlanta, captured 15 of 18 world amateur titles since 1969, won both Olympic baseball tournaments, and taken every Pan Am gold medal (and all but one game) since 1963.

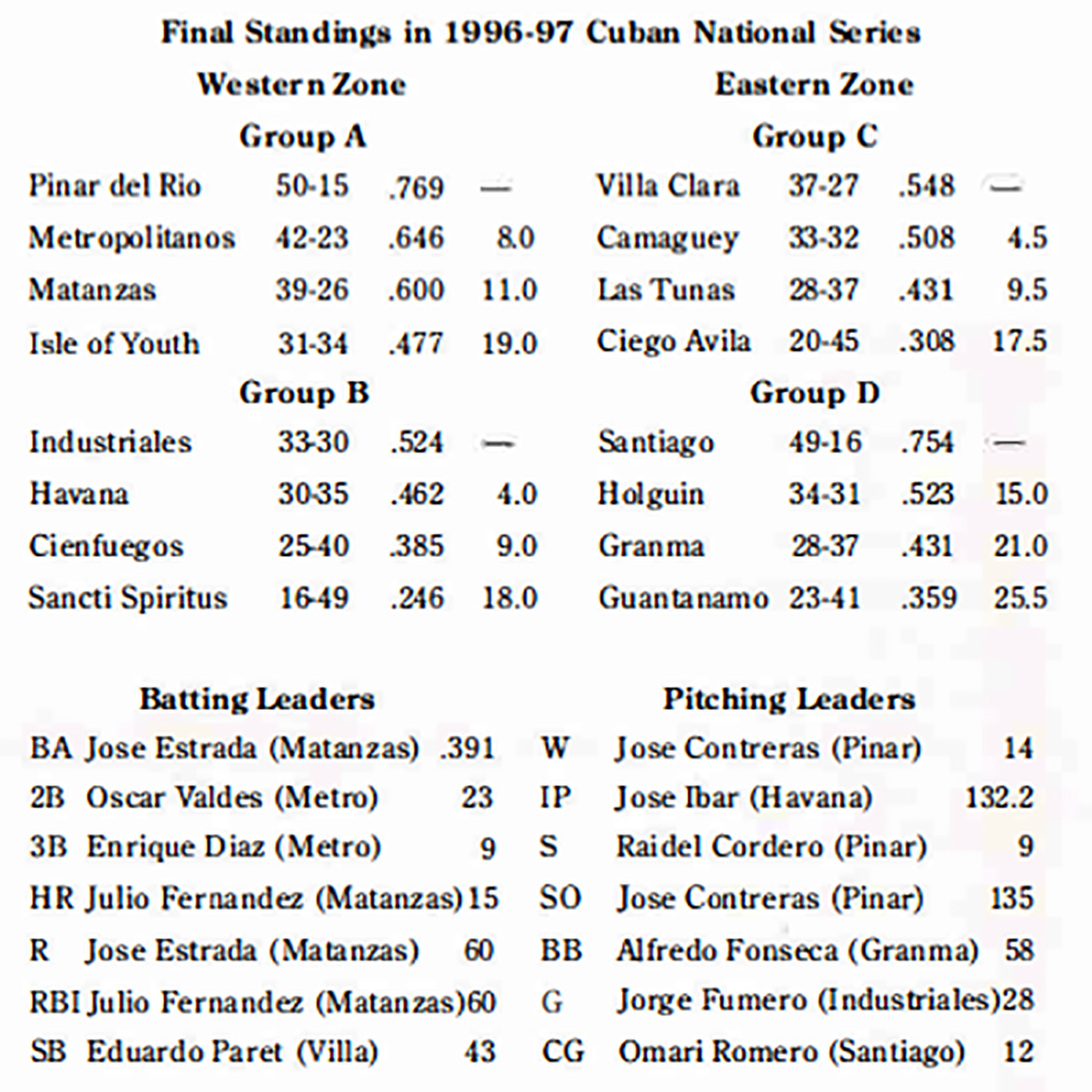

The organization of the Cuban League and the Cuban playoff system has undergone several overhauls over the decades. It now consists of a season of 65 games featuring 16 teams in 14 cities (Havana has three teams), which are divided into four divisions (two groups in the West and two in the East). A second Selected Series season with eight teams and 63 games has long been a staple of summer-season play. A February four-team postseason culminates the Series Nacional and corresponds to a stateside LCS playoff.

The showcase ballpark is still the 55,000-seat El Cerro. Impressive 25,000-plus capacity parks of AAA quality are also situated in Pinar del Rio, Matanzas, Santiago, Holguin, Cienfuegos, and several smaller cities. What gives Cuban baseball its distinctive appearance within this lavish system of amateur competition is the use of aluminum bats and a total absence of any peripheral commercialism. The one lends a strange feeling of college baseball to games staged in professional venues. The other means that no outfield or scoreboard advertisements or ear-splitting between-innings video ad campaigns contaminate pristine Cuban ballparks.

How good are these guys?

What is the status of the Cuban league and its mysterious cache of potential big-league talent? Are the Cubans really as good as their Olympic and international records suggest? Is a recent claim on the cover of a leading U.S. baseball weekly that Omar Linares is the “best third baseman on the planet” a case of overhype or a bold measure of reality? Stripped of their aluminum bats would the Cuban sluggers who dominated in Atlanta succeed against big-league hurling? Does Cuba really contain a deep untapped talent pool for big-league clubs?

Atlanta provided a clue for American fans privileged to see the Cubans’ best players firsthand. Even allowing for aluminum bats, Kindelan and Linares are awesome long ball hitters. Kindelan strokes blasts that remind one of K-brothers Killebrew and Kingman. Paret is as talented at shortstop as any major leaguer of the past several generations, flashier than Ordonez and more potent at the plate (completing this year’s National Series with a .290 BA).

There are several others with major-league potential. Miguel Caldes is an impressive outfielder some tout as the next great Cuban star. Luis Ulacia is a leadoff hitter with major-league tools, and rifle-armed Juan Manrique is potentially a solid big-league receiver. Pedro Luis Laso (11-2 with Pinar del Rio this season) demonstrated in the recent national playoffs that he has a genuine big-league arm, professional savvy, and an overpowering delivery effective even against aluminum rocket launchers.

The rest of the Cuban pitchers are not especially impressive. Jose Contreras (14-1 with Pinar del Rio) throws hard but is undisciplined and features only two pitches. Lazaro Valle is now gone from the scene, and southpaw Omar Ajete (a 1992 Olympic mainstay) is far past his best years. The best up-and-coming young arms — Rodriquez and Nunez — have already defected.

So Cuban talent is a mixed bag. Pitching is thin, but Cuban fielding and hitting is still impressive. Linares stands head and shoulders above the pack. At 28, the slugging third sacker seemed this past winter season to be losing interest. Cuban fans complain that he has put on weight and rarely hustles. But I believe Linares is the best ballplayer this island has ever produced — including Perez, Canseco, Oliva, and perhaps even 1930s-era Negro League wonder Martin Dihigo. He has been described as Brooks Robinson grafted onto Albert Belle. My impression is more along the lines of a mid-career Aaron, Mathews, or Mays. Omar Linares is as good — and as exciting — as anyone I have ever seen, with the possible exceptions of Clemente and Mantle.

The best assessment of Cuban baseball is that the talent is there but the product is waning. The same claim, of course, can be made of the majors. The crisis in Cuban baseball will only be resolved when the sport’s top leadership decides to go in one direction or the other-strict amateurism or free-market professionalism. In the meantime Cuba still harbors elements of what appears to an outsider as the last vestiges of the game we all once knew and loved-the game joyfully played more for prideful victory than for bulging bankrolls.

Table 1: Final Standings in 1996-97 Cuban National Series

(Click image to enlarge)

Table 2: Career Leaders in Castro’s Cuba

(Click image to enlarge)

Table 3: Team and Batting Champions in Castro-Era Cuban Baseball Leagues

(Click image to enlarge)