Locating Philadelphia’s Historic Ballfields

This article was written by Jerrold Casway

This article was published in SABR 50 at 50

This article was originally published in SABR’s The National Pastime, No. 13 (1993).

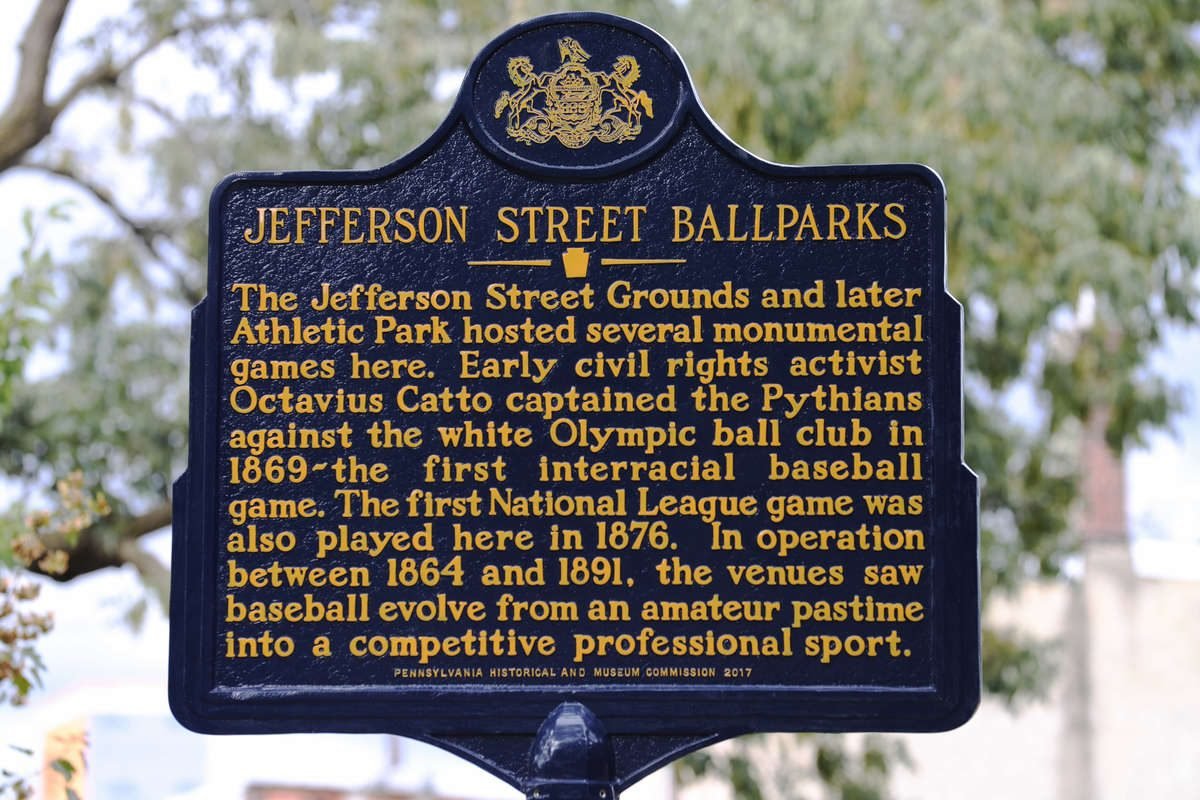

Historical marker placed at the site of Philadelphia’s Jefferson Street Grounds and Athletic Park, seen here in 2017. (Courtesy of Matt Albertson)

Accompanying an article on the growing popularity of post-Civil War baseball in the 1992 issue of The National Pastime was an insert entitled ”Where was the Jefferson Street Grounds?” Joel Spivak, who posed this question, asserted that the famous Jefferson Street ballpark of Philadelphia was located not at its actual site at 25th and Jefferson, but at 52nd Street. He credited this placement to transposed numbers. Compounding this conclusion was his claim that the great championship series between the Brooklyn Atlantics and the Philadelphia Athletics could not have been played in the confines of 15th and Columbia. In its stead, he again suggested the 52nd Street “Athletic Grounds.” Regrettably, these well-intentioned statements misrepresent the 52nd Street ball grounds, and ignore the existence of two important historic baseball sites.

The Jefferson Street grounds existed in the neighborhood of 25th Street through two ballplaying eras — 1864 to 1877 and 1883 to 1890. Another site, the famous Philadelphia Athletics ballpark at 15th and Columbia was prominent from 1865 to 1870. This is where, across from the still-extant Wagner Free Institute, the Athletics played their memorable games with their archrivals, the Atlantics of Brooklyn. As for the “Athletic Grounds” at 52nd and Jefferson, this site was nothing more than an all-purpose sports facility known as the Pennsylvania Railroad/YMCA Athletic Grounds, where amateur baseball and cricket matches were held in the 1890s.

The locations of these ballfields are attested to by daily newspaper accounts, advertisements, pictures, and contemporary local maps. From these sources the following history unfolds.

Philadelphia’s major pre-Civil War baseball teams originally played at what might have been the country’s first enclosed ball field in Camac’s Woods at 12th and Montgomery. Both the Philadelphia Olympics and the Athletics competed on this location. In 1864, the Olympics left these grounds for a new and less congested site at 25th and Jefferson. This location was leased from the city, resodded, and enclosed in 1866 by the new tenants. Until 1871 these grounds were identified solely with the Olympic Club.

Meanwhile, the Philadelphia Athletics, too, had a need to relocate from the suffocating confines of Camac’s Woods. In 1865, they moved west across Broad Street to 15th and Columbia Avenue. These grounds were resodded and rolled and enclosed with infield pavilions and a perimeter fence. The Athletics played at 15th and Columbia until 1871, when they were forced out by neighborhood developers. After their eviction, the Athletics took over the Olympics’ site at 25th and Jefferson.

By the time the Athletics relocated to 25th Street, they had become the Quaker City’s dominant ball club. They won much of their fame in the mid-1860s by playing, and often beating, the powerful New York baseball clubs. They conducted an especially bitter rivalry with the Brooklyn Atlantics, in so-called championship contests.

The Athletics played their end of this home-and-home series at 15th and Columbia. Accessible to a number of horse trolley routes, the 15th Street ball grounds drew large crowds for important games. The game of October 30, 1865, which the visiting Atlantics won 21-15, was attended by 12,000. A year later another Athletics and Atlantics game attracted a huge crowd. Estimated at about 30,000 fans, this multitude forced the postponement of the scheduled game after one inning when the playing field was overrun by spectators. Two weeks later the game was rescheduled. This time only four thousand people were admitted, at $1 a head. But over 12,000 people witnessed the Athletics’ 31-12 victory from wagons, trolleys, roof tops, and unobstructed hills. Crowds like this disrupted life for the encroaching neighborhood. By the end of 1870, local property owners sold the ballfield out from under the Athletics baseball club.

With the creation of the new National Association of Professional Baseball Players in 1871, the Athletics moved to 25th and Jefferson and won the championship. The ballfield the Athletics took over was shadowed along the third-base/Master Street side by the old grassed embankment of the Spring Garden Reservoir. But the facility and its playing grounds were in need of great repair. Wasting little time, the Athletics tore down the old grandstands and the encircling fence. They resodded and leveled the playing surface, erected a 10-foot vertical slatted fence and constructed a pair of tiered infield pavilions that abutted near the original home plate at the 25th and Master intersection. Bleacher benches extended along the outfield lines.

The new Jefferson Street grounds had a capacity of 5,000. This figure frequently was doubled for major ball games, when fans lined the outfield fences and stood on boxes and unstable raised wooden planks. Those who could not gain admission purchased 25-cent roof-top seats or climbed a convenient overhanging tree. These trees were eventually taken down, but all calls for a center-field pavilion fell on deaf ears. The club owners were too uncertain about the site’s future and their profit margins to start any renovations. Even the advent of the National League in 1876 could not save the old ball field.

The Athletics opened the new league’s first season at 25th and Jefferson, but suffering finances led to their expulsion when they could not embark on their final road trip. The old Jefferson Street grounds were left without an affiliated professional team. The Athletics’ 1877 nonleague schedule was the last season of games held on this site. At the end of that season it was obvious that more money could be made by turning the grounds over to residential developers.

It took the creation of the American Association, the new “beer ball league,” in 1882 to revive the old Philadelphia Athletics and the Jefferson Street ballfield. Unfortunately, the original 25th Street site no longer existed and its remnant, a municipally-owned lot at 27th Street, was scheduled for a high school. As a result, the Athletics played their first Association season on a small renovated post-Civil War site, known as Oakdale Park at 12th and Huntington. These grounds, however, were too small to accommodate the city’s only professional ball club. With a successful season behind them, the Athletics leased the still-vacant 27th and Jefferson Street location from the city.

On the northwest corner of 27th and Jefferson, the Athletics constructed the “handsomest ball ground in the country.” The pitcher’s mound of today’s softball field approximates the April 1883 batter’s box. This corner was backed up by a semi-circular two-tiered grandstand that later doubled as the main entrance. Painted white and adorned in “ornamented … fancy cornice work,” the pavilion offered patrons armchair seating behind a wire-mesh screen. The structure was topped by 32 private season boxes, each holding five people, and a 22-person press box. A season ticket cost $15. The grandstands sat 2,200 people, but open benches along the outfield foul lines accommodated an additional 3,000 fans. After a successful 1883 championship season, the ballpark’s capacity was increased to 15,000. Special features included a private external staircase for box ticket holders and a ladies’ toilet room with a female attendant.

Attendance was supported by the Association’s standard 25-cent admission fee and the ballfield’s accessibility to public transportation. The grounds were five blocks from the 30th and Girard Pennsylvania Railroad Station and a few squares from the busy Ridge Avenue horse-trolley routes. Because of the state’s “blue laws,” Sunday games were played at the Gloucester Park grounds in New Jersey. A ferry from the South Street wharf took fans to this ball field.

The American Association Athletics played at 27th Street until the 1891 post-Players’ League reorganization moved them to Forepaugh Park at Broad and Dauphin. This site belonged to their new owners, the Wagner brothers, who had become involved in baseball when they had invested in the defunct Philadelphia Players’ League team. In 1892, the Wagners were forced to abandon the Athletics franchise, and were compensated with a team in Washington D.C. This withdrawal left both 27th and Jefferson and Broad and Dauphin without professional occupants. Only the National League’s Philadelphia Phillies, playing in a grand wooden stadium on the southwest corner of Broad and Lehigh, remained.

The departure of the Athletics and the demise of the Jefferson Street complex did not dampen the city’s enthusiasm for baseball. Each summer, the Quaker City was preoccupied with amateur, semipro, and regional professional leagues. Playing grounds, however, were now located along the new periphery of the expanding city. Prominent among these sporting sites was a facility at 52nd and Jefferson.

Although baseball was not new to this neighborhood, it was not until the summer of 1896 that a sports park was constructed-the Pennsylvania Railroad and Y.M.C.A. Athletic Grounds. Over 12,000 loads of soil were carted to this site. A large grandstand holding 5,000 spectators was erected, together with a quarter-mile clay and cinder bike track. Tennis, croquet, and cricket were among the other sports played at this facility. But these “Athletic Grounds” were never connected with any of the Philadelphia Athletic[s] baseball clubs. Even Connie Mack’s 1901 revived American League Athletics had no association with 52nd Street. They played their first seven seasons on a converted industrial site at 29th and Columbia.

The ball grounds at 25th and Jefferson and 15th and Columbia are long gone, but they helped incubate the sport of baseball, and they deserve recognition as pioneering venues.