Lou Gorman: ‘You Don’t Win Without Good Scouts’: A GM’s Look At Scouting

This article was written by Bill Nowlin

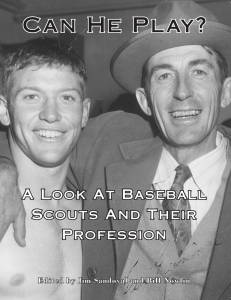

This article was published in Can He Play? A Look at Baseball Scouts and Their Profession (2011)

As a baseball executive, Lou Gorman worked for more than a third of a century with scouts. He’d been a farm director for the Orioles and Royals, director of player development with Kansas City, and GM or assistant GM with the Mariners, Mets, and Red Sox.

As a baseball executive, Lou Gorman worked for more than a third of a century with scouts. He’d been a farm director for the Orioles and Royals, director of player development with Kansas City, and GM or assistant GM with the Mariners, Mets, and Red Sox.

The Providence, Rhode Island, native was once a minor leaguer himself, albeit briefly, after signing with the Philadelphia Phillies out of high school. At the age of 19 Gorman played New England League baseball (Class B) with the 1948 Providence Grays. He appeared in 16 games, accumulating 28 at-bats. He had one hit, a single, batting .036. He was released.

Lou went on to get a couple of college degrees and served most of a decade in the United States Navy. It was in 1961 that he began working in baseball. As this book was in its infancy, Bill Nowlin interviewed Gorman, asking about his thoughts on scouts and scouting from the perspective of someone who has served as a top executive at so many teams, both with established franchises and with two expansion teams, Seattle and Kansas City.

As Gorman said, late in the interview, with justifiable pride: “No one’s ever built two expansion clubs before. In the history of the game, no one’s ever done that. When I went to Seattle, the only person there was the ownership and me. That’s it. No one else. Didn’t have a name for the team. Didn’t have a player. Didn’t have a scout. Had nothing. When I went to Kansas City, I had Cedric Tallis, myself, and we hired Charlie Metro. We had no offices. The Chamber of Commerce gave us two offices to work out of, downtown in a hotel. We had one secretary between us. Didn’t have a name for the team, didn’t have colors, didn’t have a design. We had a contest to design a logo for the club. If you look at the Hallmark cards, it’s almost the same thing – the crown. (Hallmark is based in Kansas City.) A Hallmark artist designed that. It was a contest. Fifteen people sent in designs.”

BN: Tell us a bit about your first jobs in baseball.

LG: I worked one year for the [San Francisco] Giants in Lakeland, Florida. My first job in baseball. I left the Navy. I went down to the baseball convention in 1961. Tampa, Florida. I sat in the lobby of the hotel with a résumé. Winter meetings in December. I spent the week with interviews but nothing firm came out of it. The last day I thought, “Well, I better think about what I want to do with my life.”

BN: A chance meeting in a bar led to your getting hired.

LG: This guy’s in the Hall of Fame. I go to lunch with him and his assistant. I sell myself to them. So I end up working for the Lakeland Giants my first year. I had no idea what I was doing. You run the whole thing by yourself. There’s no one there but you. No secretary. You have to sell fence signs, advertising …

BN: You were the general manager and the ticket taker?

LG: You’re it. 15 or 18 hours a day. I slept in the clubhouse half the time. This guy came over from the minor leagues and helped me a bit. We had a fairly decent year. The club didn’t do too good, but we had a fairly decent year. Tito Fuentes was on that club. Bob Bishop, who would have been a great pitcher, now scouts for the Dodgers. Hurt his arm. Opened the Double-A Eastern League and pitched a no-hitter. Pitched a three-hitter the next game and struck out 14. In the third game, he tore his shoulder. He pitched briefly later, but never again like that.

The next year, I got hired by the Pirates to run the farm team in Kinston, North Carolina. On that club was Gene Michael, Jose Martinez. Gary Waslewski. Jim Price was the catcher. Mike Derrick. Pete Petersen was the field manager, later became the general manager for the Pirates and the Yankees. His son Rick Petersen is the pitching coach for the Mets.

The next year I got hired by the Orioles. Harry Dalton was my boss, and Lee MacPhail was the big boss. I worked for them. MacPhail left when the club was sold, and Frank Cashen came into the picture. Dalton became the director of baseball operations and I became the farm and scouting director. I was there three years and we won a world championship.

After not quite six years there, the Kansas City Royals started up and a guy named Cedric Tallis was hired as the executive vice president. He called the Orioles and got permission to talk to me, and he offered me the job as director of baseball operations, to work under him and run the baseball operation. At a huge salary compared to what I was making at the time. So I took that and moved to Kansas City and spent the next 10 years there. I had hired John Schuerholz as my assistant in Baltimore. He was a schoolteacher when I hired him. I took him with me. He worked with me for ten years. And Herk Robinson was the other kind that I hired, who later became general manager and executive vice president of the Royals, too.

Before I forget, in the years at Baltimore, my minor-league managers were Earl Weaver, Darrell Johnson, Joe Altobelli, Jim Frey, Harry Malmberg, Billy DeMars.

I spent the ten years in Kansas City and ended up as vice president and director of baseball operations with them. I signed George Brett and signed…it’s in the book. I built the baseball academy. I bought the property and built the complex. We took 35 students every year, housed them, fed then, bused them to junior college, gave them an education, taught them baseball. Did that for almost seven or eight years. Syd Thrift, who later became general manager of the Pirates, I hired and put him in charge of the academy. Next, Seattle. Danny Kaye hired me. He was the managing general partner and he hired me and I began the Seattle Mariners as general manager. I worked for him for 5½ years. At that point, the club was sold. My contract had two or three more years to run. Cashen had now become president of the Mets. He called me and said, “How are you doing with the new ownership? How’d you like to come and work with me? We’re going to rebuild the Mets. I’ll take care of your contract. We’ll move you. I want you to come with me and build the Mets.”

So I leave and go to the Mets, director of baseball operations. We signed Strawberry and Gooden, Dykstra, Mitchell, Randy Myers, and the whole crew who played in the World Series. I made the trade for Sid Fernandez and Ron Darling. We ended up drafting Roger Clemens in the 12th round of the draft, but didn’t sign him. Ended up taking Schiraldi in the first round. Spent the next four or five years there, and ended up coming here [to Boston].

BN: It’s almost 50 years now. Just the list of people who worked with you who became general managers is amazing.

LG: General managers? Schuerholz.Herk Robinson.Jim Frey. Dick Balderson at one point was general manager of the Seattle Mariners. Pat Gillick. Major-league managers – Jack McKeon, I hired. Don Baylor, I drafted when I was in Baltimore. Bruce Bochy. Jerry Narron. Sam Perlozzo. Frey. Bamberger. Dave Johnson. Lou Piniella. Lee Mazzilli. Clint Hurdle, I drafted and signed. Eric Wedge. Joe Torre. Darrell Johnson.

BN: Please talk some about scouts and the general manager.

LG: Scouts are so important. You get into this sabermetric thing, and obviously the statistics. Certainly, the technology today is far more advanced beyond what we had. Obviously, we use it, but I think it’s a question of where you place the emphasis. I don’t think you could ever get away from having good scouts. You don’t win without good scouts. You as a general manager can’t see every player. Nobody can. It’s impossible. You have to rely upon their judgment on players.

I’ll give you two good stories about my GM experience that really stayed in my mind. One year, I’m with Kansas City. I’m director of baseball operations. I go to the West Coast to look at the top players before the draft. We have a scout out there named Ross Gilhousen, who’s a veteran scout, signed a lot of guys that have gone to the big leagues. He passed away about six years ago. He takes me to see a pitcher at Chapman College, a small college but a good baseball school in LA. This guy’s a left-hander and throws a good breaking ball, but I swear, he wouldn’t break a pane of glass at 10 feet. I think I could get a hit off of him. I know they’re playing San Jose State, a little better-qualified school, out of their class, and he gets hit hard. Three or four innings. We leave the ballpark, and Gilhousen says, “You didn’t like him.”

“I didn’t like him at all. I know he’s playing a better school, but I don’t think he can break a pane of glass at 10 feet.” He says, “He’s better than that.” “OK, I’ll come back in three weeks. I’ll come back and see him again.” He’s pitching, I think, against Pepperdine. I see him, and he pitches better but still not that impressive to me. So we leave the ballpark, and I say, “Listen, Rosy, I’ll take him as a fourth or fifth round draft.” “No, no, you won’t get him.” “Rosy, he can’t get college kids out. How’s he going to pitch in the big leagues?” “He’s better than that.”

So the draft is held. He’s there, all the scouts are in. Schuerholz and I are there. The first pick in the country is the Padres and they draft this guy number 1 in the nation. I nearly fall off my chair. I say, “What a hell of a scout I am! I’m a bad scout.” It was Randy Jones. And Randy Jones goes to the big leagues and wins the Cy Young about four years later. Gilhousen never let me forget it. I learned one thing: He’d seen him for two years. I’d seen him for two games. I maybe saw the two worst games he ever pitched. But he saw him over a two-year period. He saw him at his very best, mediocre, and his worst–but he saw him at his best. He knew what he could become. I learned one thing. If I go out and look at a player for two games and I’ve got a scout that’s seen him for 10 or 15 games and he likes him, I’d better stick with his judgment. [Jones was a fifth-round pick. – ed.]

BN: Isn’t that the hardest thing for a scout, to look at a kid and project what he could become?

LG: Yes. There’s two things about scouting for me. The two things you never over-project are running speed and velocity. Running speed is generally what you see is what you get. You might teach him a better break out of the box, or a better lead off first base, but you’re not going to increase his running speed. Velocity, maybe once in a while a kid might get a little stronger, a little bigger, and maybe his delivery will give you a little more, but generally speaking, when you see the guy throw 91, or 88, whatever it is, that’s where it’s going to be. He might get a little stronger and he might get a little bigger, but…

At a college age, you’re generally going to pretty well see what you’re going to get. High school, you can project a little bit on him. When a kid’s 17 or 18, he’s going to get a little bigger and a little stronger.

BN: He might get 2 or 3 or 4 more miles per hour?

LG: I’m not sure you’ll get that much, but you’ll get something on him. I remember seeing a kid one year when I was…I forget where. The pitcher was very small, very tiny. His parents were there and dad was small. I thought, I don’t think he’s going to get too much bigger.

You sometimes can look at the kid and say this kid’s going to get a little bigger. I drafted Paul Splittorff in the 22nd round of Class A. That’s like 500 players. He’s in the big leagues three years later. He’s in the Royals Hall of Fame. The only reason we got him was he had an injury his junior year and didn’t pitch well. But our scout had seen him a lot the year before and kept telling me, “Don’t worry about his injury. It’s not serious. He’s a better pitcher than that.” Based on his gut – because I believed in that scout – I drafted him. Now if you doubted the scout, you wouldn’t have drafted him. It was Don Gutteridge. He was working for me. He had seen him. As a sophomore, he was a big case but they all got off him because he didn’t pitch well the next year.

The second thing happened to me with that same scout in California. I’m out there about four years later and we go to see a kid at LaVerne College, the same conference with Chapman. This kid throws three-quarters – up about here [demonstrates] – and the ball does nothing. He had a good slider. Good command, but the fastball does nothing. We left the ballpark, and I said to Rosy, “I don’t like him, but you tell me where you want to draft him.” He said, “Take him fourth or fifth. Don’t let him go lower than four or five.” So I took him as a fifth-round selection. We get him in spring training and in camp you have all your scouts and you evaluate every player, generally week by week. You bring in the new kids and we sit and watch them each week and we evaluate them, judge them. We get in about the third week with this kid and the evaluation is – across the board: “No prospect, release. No prospect, release. No prospect.”

One of our scouts used to say “SOE”. I asked, “What do you mean SOE?” He said, “Seek other employment.” Better than saying “no prospect.”

So I called the scout and said, “Rosy, they want to release this kid.” He said, “Don’t release him. Put him on Waterloo, Iowa” John Sullivan was the manager at Waterloo. He said, “Do me a favor. Let Sullivan have him at Waterloo.” So I put him on the Waterloo club. Sullivan calls me in April and says, “Lou, this kid can’t get anybody out. He can’t pitch. It’s embarrassing to put him out in a ballgame.” I said, “OK, hold him. I’ll try to find you some more pitching. We’ll release him as soon as I can find you some more pitching.” I said, “Just use him in mopup situations to protect yourself.” They’re playing Wisconsin or someplace in a snowstorm in April and he throws him out there to protect his pitching and the kid gets hammered. When he comes out, he’s got severe tendinitis, so they disable him. About late May, he starts to bring him back and warm him up. And he says [regarding his throwing angle], he says, “I can’t get up there. It’s too sore.” So Sullivan asks, “Well, can you throw the ball from here?” [sidearm] He says, “Let me try it.” And he begins to release the ball from there. It’s Dan Quisenberry.

And I’m going to release him. Sullivan calls me up in late May and says, “Lou, you’ve got to come see him.” I said, “Why? We’re going to release him.” He said, “I don’t know how to tell you this. I think he’s a prospect.” “Wait a minute. You told me in April to release him. Now he’s a prospect. Did lightning hit him? How did he get to be a prospect?”

Quisenberry ends up going to the big leagues in four years and is the most dominant reliever in the American League for ten years. If he doesn’t get a sore arm, we’re going to release him.

I drafted Billy Beane, by the way, with the Mets. He should have been a much better player than he was. We took him in the first round – we had three first-round drafts that year, and we took him as a fill-in draft. Billy Beane out of high school was an all-state everything – baseball/football/basketball – going to go to Stanford on a full ride. Never really became as good a player as he should. I thought when Beane made a statement in the book Moneyball, he said at one point he thought of firing all his scouting staff and drafting players only by the computer. Well, you can’t measure what’s here [points to head] and what’s here [points to heart] on a computer. There’s no way in the world you can do that.

BN: When you move from one organization to another, sometimes you must come to a place that’s had a different philosophy about scouting.

LG: Scouting techniques – like when I came to the Red Sox here, you don’t know any of the scouts here. They all judge differently. They all have a different way. And your job is to interpolate that judgment. The worst thing you can ever do as a farm director or general manager is overestimate or underestimate your talent. Some guys are very conservative and some guys are very liberal. What’s a 5 to one person may be a 4 to someone else. It takes you a while, as you’re dealing with them, to learn that. You can get burned sometimes if you don’t know the scout too well. That’s why a lot of guys try to bring their own scouts – because they know their judgments.

It’s funny. Go back on the Bagwell trade. We had Bagwell for 65 games in A and 140 games in Double-A. He hits two home runs and four home runs. Nobody projected his power as above average. Everybody called him a prospect. Everybody said he’s going to be a line-drive contact hitter who could hit with some average in the big leagues. Has to move position. Can’t play third base. Got to play first base. First question I asked: Isn’t he too small to play first base? They said no, he could handle it. He can handle first base. I had two scouts see him and two managers see him, plus we saw him in spring training, and no one plussed his power. Now obviously we made a mistake projecting his power. So sometimes you get burned even with good scouts, every once in a while. But generally speaking, if you go on the percentages…George Digby, scout in Florida, he signed Boggs, he signed Greenwell. We drafted Tino Martinez on his judgment. Didn’t sign him. Anybody that Digby recommended to you, you’d listen to. You’d take his judgment.

When I was with Baltimore, we had a scout named Walter Youse, and every player that Youse would recommend, you’d take.

We had a local team that we sponsored in Baltimore. We had a local automobile dealer named Johnny’s Automobile, but we ran the club. We bought the uniforms. Our scout ran the club. Every single kid in that area that went to Missouri, Kansas State, KU, University of Iowa, all the high-school kids played on this team. This team had sent 55 kids to pro ball over the years. Curt Blefary. Larry Haney. Dave Boswell. Jim Spencer. Player after player. He ran this club, and every year, there’d be eight or nine kids drafted off this club. I remember one year a kid called me on the phone. It was about May, I guess. He said he’d just moved to the area and he said I understand you sponsor a baseball team in the area. I play some baseball and I’d like to try out for it. I said, “Here’s the number of the scout. You call him and I’m sure he’ll give you a workout.” I don’t think any more of it. We drafted some local kids and I’m in with the scout – three kids and we’re trying to get them signed to a contract. I said, “How’s your Johnny’s team?” “We’re 23-1 or something. By the way, that kid you sent us is the best player we ever had.” I said, “What kid?” He said, “The kid that called you back in May.” I said, “Oh, yeah. Let’s bring him in and work him out if he’s that good a player. Let’s take a look at him.”

Hank Bauer was the manager. I said, “Hank, can I bring a kid in this next homestand any time and have Brecheen throw b.p.” He said, “Yeah, bring him in next Wednesday.”

I’m in the office the next Wednesday. It’s about 2:15. In comes this kid from Arizona State. 18 years old. He’s on the football team as a freshman, on a football scholarship. He says, “Hi, my name is Reggie Jackson.” I said, “Mr. Young tells me you can play baseball.” He says, “Yeah, I can play baseball.” So I bring him into the clubhouse. Paul Blair calls him over and says, “Come on, kid. We’ll get you dressed for the workout.” Reggie at that time had power. He had speed. He can throw. He can do it all. I’m awed by him. The regular guys come in about 4:30. Charlie Lau. Gene Woodling. They’re by the batting cage watching. He’s hitting them into the bullpen. Line drive in the upper deck at the stadium. So Lau says to me, “Where’s this kid play in the system?” I said, “Charlie, he’s a freshman in college. He isn’t signed.” He said, “Lock the gates. Don’t let him out. You’d better sign him.” I’ll never forget that.

BN: Now you have to be drafted?

LG: You’ve got to be drafted. In those years, though, you were drafted at the end of your sophomore year, not your junior year. So I asked him could he come back. I didn’t want the White Sox to see him. I got him off the field, got him showered, took him up to the press box and fed him hot dogs and crabcakes. [Gorman asked Jackson if he could come back another day, and got some other people in to see him. He got ten tickets for Reggie. He came back the next homestand.] We had about five scouts in. John Schuerholz was there. Jim Russo was there – one of the great scouts in Baltimore’s history. Youse was there. MacPhail says, “You’re right. He’s a hell of a prospect. We’ll never get him. We’re going to draft 24. He’s going to go too high.” I said, “Well, could you get him to drop out of school?” “No, I don’t want to do that. I don’t want to influence him.” He finished playing for Johnny’s the rest of the year, and every year they have a tournament in Johnstown, Pennsylvania, called the All-America Amateur Baseball Tournament. And teams from all over the East Coast, 30 or 40 scouts come in. A huge tournament. They draw 9,000 for the games. And Reggie’s the MVP in the tournament. Every scout in the country sees him and [he] goes number 2 in the country. That’s it. Oakland takes him.

When we were in Baltimore three years, we’re going to play the Dodgers for the world championship. Koufax, Drysdale, that great Dodger ballclub. They had Russo and two other scouts do the advance on the Dodgers, and they stayed with the Dodgers for two weeks. I sat in the day they came in to talk with Bauer and the coaches and analyze the Dodgers, and the in-depth of their report just stunned me. And the in-depth of every player, how they picked them apart. How to pitch this guy, pitch that guy. What this guy does well and that guy doesn’t do well. How they play the game, how they defense. It was awesome to sit there and realize how these guys had sat there for two weeks and picked up all that information. It’s amazing to think of what advance scouting does. Clubs do that all the time, and if you’ve got guys that do that well, what a difference that is when you get that report. That to me is invaluable.

Going back to the technology thing, one of the things that impresses me, they have TV cameras in the clubhouse and every single hitter and every single pitch is recorded by these three guys on a disc. A hitter can come in if he struck out in an inning and take a look at what happened, what pitches he threw, in slow motion. Same with the pitching. What pitches he’s throwing. What guys hit off him, what he shouldn’t throw against this guy. They can take the disc back with them to the hotel room. To me, that technology is marvelous. Right in the ballgame right now, you know exactly what this guy is throwing you your last two at-bats. That is an amazing technology. I think statistics have their value. They place so much emphasis on on-base percentage, and that’s important. But somebody’s got to drive those guys in. It’s fine to get them on base but someone’s got to get them in. Slugging percentage is important. There’s 8 million statistics they give you. To me, what’s more important is how you use your 27 outs. Weaver’s theory was the most important thing I have on offense is my 27 outs. And I don’t give them up unless I can score a run. The only time I give an out up is if I can score a run. It’s still how you handle those 27 outs to earn our runs. I think sometimes we get to the point with statistical analysis that we let that dictate everything we do. You could have statistics on defensive purposes, about this guy – but you can’t judge range. Marty Barrett could get to a million balls and not make many errors but what’s his range compared to, say, Ozzie Smith?

I’ll never forget this. When I first got to Baltimore, I’m watching them work out and one day in August I’m sitting on the bench next to Bauer. I wanted to learn from these guys. And Brooks Robinson is taking groundballs. I haven’t seen much of him, because I’ve spent most of my time in the minor-league system. I look at this guy and he doesn’t throw too good. I said, “Hank, he doesn’t have a strong arm.” And he says no. I watch him a bit more and it looks like he doesn’t run too good. And Bauer says, “I know it.” So I’m curious about this guy. I go into the clubhouse the next day and I went through the files and pulled out the report. He was signed out of high school in Little Rock, Arkansas. Central High School. And the reports had him below-average hitter, below-average thrower, fringe prospect. So I thought to myself, “What makes this guy so good?”

When you began to watch him, It wasn’t his arm strength, or his running speed. It was his first-step quickness. He’d get to the ball before anyone else would ever get there. His reaction to a groundball was unbelievable. Every throw he made to first base was close. Every play at first base was bang-bang. He got to the ball so quick and got rid of the ball so quick. His release on the ball was unbelievable. How do you measure that on a computer? I don’t think you can do that.

I remember when I was in Seattle, I had Bill Mazeroski for a coach. We had a second baseman named Julio Cruz, later played for the White Sox. Cruz had a habit on the double play of jumping and making the throw instead of kicking off or pushing off as he crossed the bag. He’d get up and jump, so Darrell [Johnson] said, “Geez, get him out of that damn habit. Maz, go help him.” I happened to be watching the workout one day at the Kingdome. Maz is working with him and they’d hit a ball to shortstop, and I said, “I don’t think the ball is hitting his glove. I don’t think the ball is hitting Mazeroski’s glove. It’s just gone.” I walked out and stood there and said, “Maz, is that ball hitting your glove?” and he said, “I don’t know.” “You don’t know if the ball is hitting your glove?” and he said, “No.” “Can we try it again?” “Sure.” That ball never touched his glove; that ball was just gone. I don’t know how you teach that. All of a sudden, the ball was gone. Sometimes the quickness of things like that doesn’t show up in a statistic. There are things about a player… now, I think the statistics can tell you things. When a player has played in the minor leagues, you have at least a norm of judgment to grade him. Those statistics can be important. It’s something you use, but it doesn’t dominate our judgment. There’s just so many…I can go back on a thousand stories.…I remember one year when I was in Kansas City. Bob Lemon’s the manager. He asked me, “Have you got anybody in Triple-A? Left-hand pitching, that can help me?” I said, “No.” I’ve got a kid named Steve Mingori, a kid named Bobby McClure. I don’t think they can pitch in the big leagues. He said, well, let’s bring them into spring training. Both of them made the club. Mingori spent ten years in the big leagues. McClure spent 19 years in the big leagues. He’s a Triple-A pitching coach right now. What I saw of him, I didn’t think he could throw hard enough to get left-hand hitters out. But he had that good curveball; he had a good change. They both picked up that split-finger thing. All of a sudden, they could pitch in the big leagues. [Mingori and McClure were signed at different times. – ed.]

When I’m with the Mets, my Triple-A shortstop’s Ron Gardenhire. One of my scouts is Terry Ryan. The Triple-A club, Tidewater, has Jeff Reardon, Mike Scott, Greg Harris…there’s four guys on that club that pitched in the big leagues [not all in the same season]. So Scott comes up and doesn’t pitch well. Nobody likes him. They think he’s a fringy guy. I come here to the Red Sox and they trade him to Houston. Al Rosen’s their general manager. He gets them. He was pitching awful. Rosen’s about ready to release him. He calls Roger Craig, who’s a friend of his. Rosen says, “Do me a favor. If I send a kid down to you, could you teach him that split-finger fastball?” So he sent him down to Craig, on a high-school field, and Scott picks it up like that. He goes back the next year and wins 18 games. The fourth year, they face the Mets for the National League pennant and he wins the Cy Young. You think back on that guy, and if you looked at him at that time and projected him, based on the statistics you had, you’d say he’s not going to pitch in the big leagues. You can get fooled so many times on judgments.

BN: What about guys who got really good reports, who looked really good on paper, everything just looked good, but they just didn’t have what it took?

LG: The best example of that in my mind was Dave Kingman. If you worked Dave Kingman out in the ballpark, you’d give him anything he wanted. He’d give you plus power. If you rate from 1 to 8, with 5 as average, he’d be 7-8 power. You try to grade to the Major League Scouting Bureau system. You’re going to use their reports. You might as well use the same reports.

You watch this guy, he could hit balls 500 feet. He could throw. He could run for a big guy. He was a big strong guy. You’d look at this guy and think, “God damn, this guy’s going to hit 50 home runs everywhere he plays.” He’s going to be a very good defensive outfielder. You’ve got to sign this guy. Give him everything he wants. He never became…it’s almost a conundrum to look at this guy. Why wasn’t he a better player? It wasn’t through lack of effort. I remember one year, the second or third year in Kansas City, the scouting director asked, “Where’s that guy Kingman?” He said, “Can you get him?” I said, “Yeah, they’d probably trade him, for some backup catching or an extra relief pitcher.” He said, “Get him. I can work with Kingman. I can teach him to hit.” I said, “Joe, we’ve had eight million guys work with him. No one’s done it.” So I get him and we put him on the Triple-A club. Goes to Omaha. This is a guy who’d been in the big leagues four or five or six years. He busts his ass down there. Plays hard. He’s a great teammate on the club. It wasn’t lack of effort, but he never could put it together. How do you figure? It didn’t come together. [Note: Kingman was never in the Royals (or Braves) organization and didn’t play in the minors after he was first brought up to the majors until he was 38 years old.] That is always the dilemma to me. I had Mike Epstein. He had tremendous power. Very intelligent kid. Went to the big leagues, played for seven or eight years, but never became.… First year we had him in Stockton, hits 30 home runs. I jump him to Triple-A, he hits 29 home runs. Minor League Player of the Year. But never becomes that player in the big leagues.

Take Carlton Fisk now. When Fisk is at Double-A, they don’t think Fisk is going to be a big-league catcher. Maybe a backup at best. I think they made a trade for someone, as I remember, when they brought Fisk up. They felt Fisk wasn’t going to do it. Fisk ends up in the Hall of Fame. How did he progress beyond that point? What takes a player at a certain stage and brings him beyond?

The first year of spring training in Kansas City, we only have about 65 players. We’re just starting with the big-league club. I’m down at the minor-league club with John Schuerholz. And Charlie Metro is one of our special-assignment scouts. We got about 55 or 60 kids. Some we’ve signed. Some are released players. We drafted a few kids. So they’re doing their laps around the ballclub. They’ve only run about two or three laps and Metro says to me, “Release that kid.” I say, “Why?” “He’s got a bad face.” “What? What do you mean, he’s got a bad face?” The old scouts could judge by his face, his visage. If they didn’t think he looked like a competitor, they wouldn’t think he could play. It was an old theory, going back to Branch Rickey thing. “Charlie, let him throw a baseball first.”

Another story. Ewing Kaufman, the owner, comes in the office and he’s puffing his pipe. He sees the board behind me. I think we only had four minor-league clubs at that time, and we had a limited number of players. He said, “Go to the board and point me out your prospects.” So, I go to the board and say, “We think this boy…and we think this boy….” He said, “All those boys aren’t prospects?” I said, “No, some of them will get better. Some of them are fringe, and some of them aren’t, but you need them to help develop your prospects.” He said, “No. I want you to release the nonprospects and put them all on one club.” I said, “You can’t do that. Certain players mature at different levels. If I take a kid at the rookie level and put him in Triple-A, it’s like taking a kid from the ninth grade and putting him in graduate school. He’d be totally overmatched, and he’d lose his confidence totally.” He’s thinking save the money. I remember when I was in Baltimore. We had Paul Blair. We picked him up as a $10,000 acquisition. Blair hit A ball and hit, I’ll say, .260. So he goes to the big-league camp, and at that time we didn’t have a good center fielder. He could always run and throw and go get the ball. So, he goes onto the big-league roster and Bauer sees him right away and says, “He’s my center fielder.” So, we have a meeting – MacPhail and Dalton and I – and we say we’re going to play him at Double-A, he’s not ready to play in the big leagues. “No, no, he’s my center fielder. He’s the best outfielder I’ve got.” “He can’t hit there.” “No, he’s going to open the season for me.” He was so bad the fans were booing him. Our ticket manager, a big, big baseball fan, came to me and said, “Why the hell did you get that guy? He couldn’t play in the Little Leagues.” “No, no. He’s just overmatched.” He spent most of the year in Double-A and he struggled there all year. When he came back in September, when you have the call-up, MacPhail was saying, “Let’s all pray he gets a base hit.” It took him two years to find himself. Certain players can handle a certain level, but if you put them beyond that level, once they lose their confidence, they’re in trouble. You reach the point… one of the great trades, I think, was when Duquette traded Heathcliff Slocumb for [Jason] Varitek and [Derek] Lowe. Slocumb had lost his confidence. He couldn’t get anybody out. Same with a young player, when you put him at a level he can’t handle, you’re going to run the risk of losing him. You’re going to have to put them at their level.

Now some players can move fast. Paul Splittorff, college player, went to Corning, bang, Triple-A, bang, the big leagues. Brett – three years and he’s in the big leagues. But I had Al Cowens, who played ten years in the big leagues. Cowens went rookie league, A league, Double-A league…but he became a big-league player. He matured at a different level. I think you have to be able to read that in a player.

The other thing to know, kids in California, Florida, that play baseball all year, against better competition, are advanced against kids from the East. When you go to spring training, it’s easy to make a judgment on a kid from the East and say, “Well, I’m not sure….” but keep in mind he hasn’t played a lot, hasn’t faced the same competition. He might take a little longer to develop. To be able to read those things is important.

Scouting will never be an exact science. It will always be an inexact science. But when you’ve got people with good judgment and you know their judgment is good, you can push your neck out for them because most of the time, they’re going to be right for you. Everybody will make a mistake once in a while. But 99 percent of those guys…there are scouts that I know…Joe McIlvaine, who used to work as my scouting director, is one of the best judges of high school talent I’ve ever been around. I remember when I was with the Mets, I went to see Dwight Gooden pitch. I liked him a great deal. But I saw a shortstop at a high school in Brooklyn named Shawon Dunston. Dunston was the best hitter at high school that I’ve ever seen. That I’ve ever seen. You’d go to games and the clubs wouldn’t pitch to him. I went to a game, and I had my Mets jacket on. There were about ten scouts there. A coach came up to me and said, “Are you with the Mets?” I said, “Yeah.” He said, “Do you want to see Dunston hit?” He said, “OK, I’ll have them pitch to him for you.” He hit balls out of the ballpark like big leaguers hit! I thought that this kid had a chance to lead the league in hitting, he was that good. He played in the big leagues for 14 years, but never ever became…. So, I sent McIlvaine to see him. He said, “How would you compare him with Dwight Gooden?” I said, “How would you compare him?” He said, “Gooden’s a better prospect.” I said, “If you feel that way, don’t worry about him. I’ll take Gooden.” We had the fifth pick. Dunston became the number 1 pick in the country. The Cubs took him. But he never became as good a hitter as I thought he would become. He faced the same kind of competition as Gooden did.

On the other hand, I go to see a kid up in Hazard, Kentucky. A kid that played shortstop for the San Francisco Giants for about nine years. Johnny LeMaster. They’re playing on a high-school field that actually had been a cornfield. A cornfield! It was like this – bumpy and slanted. There are 16-, 17-, 18-year-old kids. They’re all spitting tobacco. If you looked at this kid and said, “How would I ever think he’s going to be a big-league shortstop?”

BN: International scouting is a whole different area. When you first began, was there much of anything in the way of international scouting?

LG: No. The only clubs that were big at that time were the Giants and the Pirates. The Pirates had a scout named Howie Haak, who was a legend. Howie Haak was involved in signing Clemente if I’m not mistaken. He was a legend in the Latin countries. They loved him. He would go down there, and the Pirates would sign player after player after player out of there. We didn’t do a good job, even in my years here, in Latin scouting. It was an area I felt we were very deficient in. It was maybe my fault for not pushing it. We never did a good job down in the Latin countries. I think the advent of putting those camps down there is tremendous. The Dodgers had them for a long time. Campanis was a legend down there too. Haak and Campanis, they spent years down there. The Pirates had them for a long time. Houston had them for a long time. The Red Sox finally did it when Theo took over [under GM Dan Duquette, the Sox shared a complex with the Hiroshima Carp]. Those are important to do. The kids down there, they look at a Sosa, a Manny Ramirez, a Pedro – and they want to be like them. It’s their ticket out of poverty. I’ve been at tryout camps down there. With the Mets, I went down three or four times to the Dominican and we ran a tryout camp at a town near La Romana. About 50 kids showed up, and all those kids wanted when the tryout was over was to know, can we give them balls and bats? They can’t afford a ball and bat. A bat was a big thing for them. We gave all we had. They love baseball down there. They play it with sticks and stones. I think that Latin scouting was something that the Giants and Pirates were way ahead of everybody else.

As a kid growing up in the ’40s, I remember they had those traveling all-star teams. They had teams would go to Hawaii and to Japan. Same thing in winter ball. The players didn’t make the money they make today. They’d all go to winter ball to make the extra money, play in San Juan to get the extra money.

It’s getting more and more expensive. In the early days, the Giants would sign 8 or 10 or 12 kids and just ship them over here maybe $500 as a signing bonus. Rickey’s theory was…when I was in Baltimore, a guy who joined us later on, a guy named Walter Shannon, he’d scouted for the Cardinals for 27 years. I used to love to listen to him talk about scouting. He’d worked for Rickey for years. He told us stories. They’d hold tryout camps all over the country. They had two criteria: if they could run and throw, sign them. Great speed, great arm? Sign them. If they hit, we’ve got a prospect. If they don’t, we release them. Their theory was: If they could run and throw, if we sign enough of these guys, eventually we’ll get some hitters. And when we get a hitter combined with the other skills, we’ve got a ballplayer. And you weren’t paying any money. They’d sign for a bonus – $100, $500. They had 17 farm clubs. When I signed with the Phillies, they had 15 minor-league clubs. I went to spring training as a kid with Del Ennis and Robin Roberts and Puddinhead Jones. They were all kids. I didn’t know who they were. They had two minor-league camps in spring training. They had 300 or 400 kids in spring training. Today, you can’t afford that. You draft now. Your number 1 draft – [Craig] Hansen, what’d he get, $4 or $5 million? That would run your whole minor-league system. Today, your number 1 draft is getting X. Your number 2 is getting X. In those days, you could just sign a kid for a contract, for a chance to play. You could run 15 clubs for what you pay today for four or five.

The advent of the camps has been a great, great thing.

One year when I was in Seattle, I brought the Hanshin Tigers to train with us in spring training. They trained with us for four years. Worked out a schedule to play the Giants, the Cubs, the Indians. It was fun being around them and working with them. They loved baseball, and they loved to play you and beat you.

There’s baseball in Italy now. Major League Baseball sends a team to different…for example, in the World Baseball Classic, Bruce Hurst was the pitching coach for the China team. He was pitching coach to the Chinese team. Bruce told me that a couple of years ago, he had spent almost seven weeks in Italy working with the Italian team. Korea’s starting to get more into it.

Let’s talk about scouting. If Minnesota had Ortiz right now, it would change their whole … how’d they let Ortiz go? I think back a couple of years ago, when Houston let Johan Santana go…they had Clemens, Pettitte, Oswalt, and Santana. Think of that pitching staff. Pedro Martinez was let go by the Dodgers. Lasorda thought he wasn’t going to be able to pitch in the big leagues and they traded him to Duquette for DeShields.

BN: Haywood Sullivan had been a scout and a scouting director. Some general managers and owners are more attuned to scouting… LG: Schuerholz was. You know who is really good? Gillick. He’s a baseball junkie, if I can use that term. He’s deep into baseball theory and ideas. Signed by the Orioles, pitched in the system a number of years. Very intelligent guy, loves the game, loves the scouting end of it. Built the Toronto Blue Jays into a couple of world championships. Gillick is more standard, old school. Terry Ryan’s old school.

Another guy that is a very good judge of talent is Jack Zduriencik of the Milwaukee Brewers. His title is special assistant to the GM and director of amateur scouting. I don’t know Ken Williams of the White Sox that well, but he was a scout most of his life. Dayton Moore in Kansas City, Schuerholz tells me he’s going to be outstanding.

BN: You used to have all the scouts come in and work the winter meetings? Does that still happen now? Do all the scouts come in for that purpose?

LG: You bring in about six to eight scouts, your top guys. Generally, they work the lobby. What they’re looking for is to pick up information, tidbits. You’d assign each guy to, say, the Braves, the Giants, and the Dodgers. See what they’re looking for, what they want to trade. Each guy was assigned. Each day we’d get back together again, say at lunch, and say, “OK, I talked with this guy. It looks like they would consider trading this guy and this guy and this guy, and they’re looking for this and this.” By the end of the second day, you’d have a pretty good feel who is going to move who, what might be available, what you’re going to have to do to make a move. They all operate the same way.

The GMs generally stay up in the suites. Then what you do is you call the other club. When we did the Lee Smith trade, I had rumors that Jim Frey, who had worked for me and was the Cubs’ general manager then, they were unhappy with Lee Smith. The scouts picked that up in the lobby. They said, “Look, I think that Smith is available.” “What are they looking for?” “They’re looking for pitching.” So, we discussed what we could do. Well, we could move Nipper. Maybe move Schiraldi. Smith would give you an outstanding reliever. We had a little depth in pitching at that time. We had Schiraldi at that time. Hurst and Clemens. Oil Can Boyd. So, we knew that there was a possibility. I called and said, “Jim, if you’ve got an opening, I’d like to come and talk with you.” We met the next day around 10 or 11 o’clock. We’d sit there and chitchat, then finally I said, “We’re looking to try to help our bullpen. Is there anybody you’re moving?” They said, “Well, we might consider moving Smith if we got some pitching back.” I think Zimmer was the manager there. We ended up talking about it, and he brought up Smith’s name. I said, “Well, we could talk about Nipper to you. Why don’t you bring up some other names?” They brought up three or four and one of the names was Schiraldi, so we were able to put together a trade. We talked the next day and worked it out. When we made the trade, everybody said, “He’s injured. He can’t pitch.” Someone said he fell down the Mets steps and he hurt his back and he can’t pitch. Our reports said there wasn’t any injury at all. We thought he was OK, and of course he was.

Once in a while you get burned. We got burned on the Matt Young thing. Our reports didn’t show that Matt Young could not hold a runner at first base. I mean, how could you not pick that up? How do you not pick that up? If he walked a guy, it was a double. A single was a double. He can’t hold them on. We were desperate for a left-hander. I read through the reports and the reports didn’t give any indication that he had that problem at all. No one seemed to indicate that when we talked to them. Sometimes you’re going to get fooled on that sort of thing. You’re going to make a mistake. I hadn’t seen Young except based on the reports.

BN: You might see somebody three or four games, and the pitcher doesn’t have a play at first…

LG: Yeah. And there are occasions…when Dan [Duquette] signed Pedro, he knew what Pedro could do. He had Pedro [when he was GM in Montreal.] I knew Spike Owen. I’d seen Owen play 8 or 10 times. I knew Baylor. Some players you’ll know yourself, but there are a lot that you don’t know and you’ve got to go on the judgment of the people who are doing it.

BN: Would you convene the scouts any other time of year?

LG: Oh yes. Every year, first off, in spring training you’d bring in certain scouts. We had a scout one year in Baltimore who had scouted for the Phillies for 17 years. We had him about three years with us. Dalton said, “Gee, that guy’s judgment is awful. So inconsistent. I don’t think we can hold on to him. We get burned by his judgment.” I said, “Harry, why don’t we bring him to spring camp and let him sit there with our other scouts and look at the players we’ve got in camp and let him see who we think are prospects and who we don’t think are prospects, and see if that helps his judgment. At least it gives him a frame of judgment.” You see kids in a certain area where the competition isn’t so good, and the best kid in that league becomes the best player in your mind.

BN: That’s why I was good when I was a kid. No competition.

LG: Well, we were all that way. So we brought him into the spring camp and we had him sit there. “Do you like this kid?” “Yeah.” “Well, that kid’s name is Jim Palmer.” Mark Belanger. Sparky Lyle. I asked, “Why do you like him? Tell me why you like him or why you don’t like him.” We’d break it down. The other scouts would talk to him. We left camp and he said, “Lou, this is the best thing that ever happened to me as a scout. My frame of reference is so much better now than when I came in. Thank you for doing this.” But it never changed. He never got off that, and eventually he ended up getting let go.

You have other guys, you do that for him…Gary Rajsich, who scouts for us now, I had him as a player with the Mets. He was a first baseman with the Mets club and I loved the guy. I said, “Gary, I’d like you to stay in the game as a scout.” I said, “Dan, this guy is a good quality guy, he’s played baseball at a high level. Good college player.” “Nah, we don’t have a job for him.” So he went to that scouts school. They have a scouts school, and they rated him highly in the scouts school. So finally Duquette said, “Maybe you’re right” and we hired him, and he’s become one of our better scouts. He’s one of the guys who helped with this kid we just signed, this Bard kid. Daniel Bard. Sometimes guys have a feel for it, and sometimes they don’t. You can’t change that. There are so many cases of a scout whose judgment will get better. Some never get better. Some, because his frame of reference is bad.

We bring them in to spring training – six or seven of them – so they see the talent in the system, and they help with judgment and evaluation. Then at the end of the season, we have a scouts and managers meeting. Every year. Bring all your scouts in, all your managers in. We sit for five or six days. Bring them all in. We do it in Florida, and we do it while the instructional league is going on. We meet in the morning, then go watch the game in the afternoon. Bring them back and have a light dinner and discuss the kids in the program. Do that for two or three days, then the last two days purely just discuss the players. Have a cocktail party and get to build a little morale, get to know them better. We do that every year. You’re always constantly working with them. You’ll call them on the phone. You’ll have them call you on the phone a lot. Get a feel for them, get to learn our judgment. From their standpoint, they get to see the whole system, to hear other scouts evaluate. You do that constantly. It’s the way you build morale, it’s the way you build judgment, and it’s the way you build an organization. We would do that every year. Then we’d go to the general managers’ meeting. That’s generally held right after the instructional league is over. All the GMs come in. You get a chance to feel out what might be available, meet for lunch, meet for dinner.

BN: In your book, you talk about the very detailed scouting reports that the Red Sox had on the Mets in 1986. You had just come over here from the Mets. How do you think the detail stacks up today?

LG: Much more. Much more in depth. The scouting quality and the depth of it is much greater. They have so much more means to do it. They’ll film things. You’ve got scouts that are territory scouts, grassroots scouts, but then you have the double-checkers and the top scouts that do the pregame coverage, the advance scouts. They would have video with them. They all have computers. They all have every technical thing you can give them to deal with it. They can tie their reports into the computer and feed it to you right away. I think the technology that they work with is greater and I think that they do a lot more in-depth reporting. You have a lot more clubs now that do a lot more statistical compilation than clubs did in the past. I think it’s good. No question, you use it. It’s just a question of where you place the emphasis.

The computer has a role. You don’t overlook it. A lot of things that you do today, you can’t overlook. But you can’t let it absorb you. It’s got to be, I’ve got this part of information. I’ve got this part and I put it together. Not this that dominates everything. Marge Schott’s quote is, I think, like Moneyball, they paint the scouts as idiots. Guys that chew tobacco and play on the road, old theories and old ideas. Marge Schott used to say, “I don’t know what we pay scouts for. All they do is go to ballgames and watch players.” That’s what their job is!

I watch scouts many times in the ballpark. They’ll be talking, but their eyes are never off the player. They can be talking, but their eyes are always focused on the player. People look at them and say they’re strange characters, they’re old school, it’s the buddy system. Yeah, but if he’s not doing a good job, you don’t keep him. Your job rests upon their judgment, too. They all have contracts. Some have a one-year, some have a two- or three-year, but they have a contract. If you had your scouting and no statistics, I’d want the statistics.

I’d want to look at them. I’d look at the conference the guy’s in. One conference is better than another. One is not so good. High-school baseball in Florida and California, Michigan and upstate New York is much better than in other parts of the country. You begin to look at this and say how does this shape up vis-a-vis this area. You have to know how to weigh the statistical information, and what its import is, and what its value is.

BN: Would you have one of those old scouting reports from ‘86?

LG: They’re probably all filed away at Iron Mountain. Most of the ones we had here, when Dan took over, we sent to Iron Mountain. You’re getting reports constantly all year long. The manager would file a midseason and an end of the season report. Besides our club, you’d report on every other club in the league. The one thing your manager’s going to tell you on your own team, he’s had them for 140 games. He knows their makeup, their work ethic, how they handle failure, how they handle winning, what kind of a team player they are, what kind of a competitive spirit they have. That value of the makeup is important. A scout might not see that. He can judge his physical skill.

We did something called the “Whole Player” which we started in Baltimore. We drew a circle. Across the top part of the circle, we tried to evaluate all the physical skills you could see. The lower half of the circle was what you couldn’t see – the psychological part of it, all of the things that determine what kind of a competitive player… Things you can’t see, how do you find those out? How do you decide? You can watch him in games, see what kind of drive he has in the ballgame, what kind of desire he has.

BN: An area scout will probably want to spend as much time as he can with the family.

LG: Exactly. Plus with the coach, guidance counselor, peers on the club. The best judge of a player is his peers, the guys who play with him. You don’t fool them.

You try to get to the teachers, the guidance counselor, his teammates. Get as close as you can to the people around him. You talk to his parents, but his parents might give you a different perspective. They might look at it through rose-colored glasses. You want to know, how is he when things aren’t going well, when he’s struggling, how does he handle that? How does he handle it when things are going good? How hard does he work every day? You ask the scout to get as much of that as you possibly can. This is important. You can have guys with all of these skills [top of the chart] but don’t have this [bottom of chart], but if you get a guy with all of these skills and good makeup, you’ve got a chance to have a great player.

[On the Whole Player circle] When I was in Baltimore, one day we were sitting with the scouts talking about physical skills. Schuerholz and Dalton and I were talking about it and we decided to draw up a picture of it. When I went to Kansas City, I had it there. When Metro came over, he had been with the Dodgers and the Cubs, so he brought all the Dodgers books with him. We took all their books, and we created our own book. We had a book, for example, on how to scout, how to evaluate, for full-time scouts and part-time scouts. We took all the Dodgers theories and ideas and all the Orioles theories and ideas and I used those and combined them with Kansas City’s. Went to Seattle, we did pretty much the same thing. When I went to the Mets, we did the same thing there. Cashen, of course, knew the thing. Charles Steinberg talks about it all the time. He loves that circle. It was a way to show the scouts about the nonphysical skills.

The evaluation of the minor-league staff was always good to get. They may not sometimes be as good a judge of the physical skills as the nonphysical ones: how intense is he? How does he handle failure?

You can judge speed and velocity with the guns today. You can judge quickness with the bat. A lot of things you can’t pick up…I had a kid one year that we drafted. A number 1 draft. A kid out of Texas. His name was Rex Goodsen. He came into camp. We gave him a big signing bonus – I say big, it was like $150,000 in those days. He played at San Jose, in his third year, made the all-state all-star team, hit about .330, stole about 40 bases. Next year, came to camp went to Double-A. The next year, was in camp about a week and said, “I want to quit.” I said, “What do you mean, you want to quit, Rex?” He said, “I don’t have the desire to play anymore.” “What do you mean you don’t have the desire to play?” He said, “I don’t want to play. I don’t enjoy it.” I said, “Rex, our guys think you have a chance to be a big-league player. A chance to make a lot of money in this game if you play in the big leagues.” “I just don’t have any desire to play anymore. I want to quit.” I was stunned. We talked and talked, and I said, “Why don’t you think about it a while? Just wait a week. We’ll talk in a while.”

So, he stayed around, and he came back in about a week and said, “I haven’t changed my mind. I want to quit.” So, we put him on the voluntarily retired list. He went home. Went to Texas, I think Texas Christian or Texas A&M, played a little bit of football but then dropped out of school. Many years later, I asked around and found out he was running a Gulf gas station. He just lost his desire to play. That’s strange for a kid to do that. It just happened. You went back and read all the scouts’ reports and they all thought he’s got good makeup, he’s a hard worker, he’s a good competitor, a tough kid…but all of a sudden, he just lost that desire. That’s an unusual thing to happen.

One of the funny things that happened, Joe Gordon was my minor-league manager running the minor-league spring training and in those days in the ’70s kids had the real long hair. So, we had a rule about cutting the hair, reasonable. We had a kid named Joe Zdeb – later played in the big leagues. Decent backup outfielder. He came into camp with the hair way down to here and Gordon wouldn’t give him a uniform. He said, “I want to see Mr. Gorman.” “Fine, but you’re not getting a uniform.” So, Joe called me on the phone, he says, “He’s coming up to see you. Don’t give in to him. Make him cut his hair.”

So up comes Zdeb and the secretary brings him in. I said, “Joe, what’s on your mind?” He said, “Mr. Gordon won’t give me a uniform.” I said, “Well, Joe, I can see why. Your hair’s a little too long and we have a rule about cutting your hair.” He said, “Can I ask you a question?” I said, “Certainly.” He said, “If I cut my hair, am I a better player?” That’s a deep philosophical question. It kind of stunned you a little bit. I said, “Joe, you’re right. It has no bearing on your ability. No bearing at all. If you had hair all the way down your back, it has no bearing on your ability to play. The only thing is that you represent the organization. It says, ‘Kansas City.’ It doesn’t say ‘Joe Zdeb,’ it says, ‘Kansas City.’ You represent more than you. You represent an organization. And that’s our rule. You represent the city and the organization and the entire people in the ownership. If you want to wear it where it says, ‘Kansas City’ you have to cut your hair.” “I won’t cut my hair.” “Fine, don’t get a uniform.” He walked out, but he came back two days later and cut his hair and played a little bit, played Triple-A and then finally got briefly to the big leagues.

BN: Just like Johnny Damon joining the Yankees.

LG: Yes, a good example. If you went to Marine boot camp… when I went to OCS, I had a Marine gunnery sergeant, an assistant company officer, for 22 weeks in your face from 6 in the morning until 9 at night, and he’d pound that stuff about wearing your uniform properly. You represent your country, not you.

Some of the kids will hit you with questions. Floor you sometimes. Much more today than the old days. When I went to camp, you didn’t ask anybody. You didn’t want to even see anybody. If the farm director ever talked to you, you’d be afraid of getting cut. I’d want to avoid him, not get near him.

Today, the kids will ask you why do I have to do this, why do I have to do that? To be able to give them an answer is important to them sometimes.

It’s funny. I won’t mention the guy. He was a great major-league ballplayer. I hired him as a minor-league hitting coach. I loved talking to him. He was terrific. But he couldn’t communicate. I remember one day, Brett came to me and said, “Mr. Gorman, can I talk to you?” I said, “Yes, George.” He said, “I like so-and-so, but I get confused with him. I’d rather he didn’t work with me.” Now when you get to that point that the players starts saying he gets confused, you just can’t keep him here. I can’t have him teach any more. I had to let the guy go. A two-year contract and I had to let him go. You feel badly about it because the guy was a pretty good major-league player. But he couldn’t communicate.

You could take Stan Musial tomorrow and I’ll bet you he could not teach anybody with that crazy stance he had. He just did it with pure ability. You got a guy like Charlie Lau, who was a very marginal big-league catcher – and not much of a hitter – who was a tremendous teacher of hitting. He could communicate, and he had theories and ideas. He couldn’t do it, but he could teach it.

I used to tell managers: Don’t hire someone because he’s your friend. If he’s not good, you’re going to get fired. You want to hire someone who can help you become a better manager. If he can’t help you, it’s going to hurt you.

BN: Are there semiannual evaluations of scouts?

LG: Yes. What we would do, in the front office, is sit and evaluate the staff – the minor-league staff, the minor-league managers, the coaches. That’s when we talked about Butch Hobson. Hobson had gone to a Double-A club and taken them to the Eastern League finals. Then he took the Pawtucket club – 27½ games out of first place the year before – and took them into the International League playoffs. He was also picked as the Minor League Manager of the Year by Baseball America, and the International League Manager of the year. All of the people in the organization said to us, “We think he can manage in the big leagues.” Based on their evaluations, I brought him in and had Haywood and [John] Harrington evaluate him. We spent four hours quizzing him on this and that and they all thought his answers were great. Hire him! And yet here’s a guy we should have known…because we had him in our system…maybe we didn’t do as good a job with him as we should have.

When you’ve got somebody in your system, I think you want to evaluate every single one of those people. If you’ve got a scout that can’t be productive for you, maybe you can’t keep him. Guys that are good will always have a job.

BN: Is there a lot of back and forth between organizations?

LG: A lot of times what will happen is that ownership changes or management changes, and they want to bring their own people in. I remember when the Major League Scouting Bureau was first formed. The intention was to cut down on the number of scouts you had and save money by having this national group to provide coverage and give you reports. All you would do is double-check their reports and provide your own judgment. The original intention was that each club would protect only eight or nine scouts; all the rest could be selected by the Bureau. Your first thought was to protect your best scouts. Then it became 10, then it became 12, then it became 13 that everybody kept. When I was with Kansas City, we had a very good scouting staff. We had about 30 good scouts. I had to put some scouts out, to be in that, because they were really good scouts. I called the director and I said, “Look, the people I’m leaving out are damn good scouts. They could help any organization.” Sometimes you let people go, but not because you want to.

On the other hand, when new ownership comes in, new baseball operations people, they want to bring their own people in. Generally, the good scouts are known and someone picks them up right away. Sometimes scouts will change jobs, but often not because they’re not good. It’s just because someone else brings their own scouts in. When you deal with someone, you have no idea how good their judgment is.

Theo brought in some of his people. Duquette did the same. He brought [Ben] Cherington in, and [Dave] Jauss in. When I came, they didn’t want to do that here. They wanted to stay with what we had here. It was a question of me adjusting to them. They had people who were good. Sometimes you might like to have one or two of your own people, you can send in to make a judgment.

BN: With cross-checking, you have two or three scouts seeing the same players sometimes.

LG: Generally for your cross-checkers and your advance scouts, you use your top guys and you use them all the time. When you come here, though, you don’t know them. You don’t know their judgment. How conservative or liberal they are. You learn it as you work with them. Interpreting their judgment is vitally important. Even if you know your own people, you’ve still got to be able to read their judgments correctly. You can misread it. You can misread a guy’s evaluation of a player. That’s happened a few times to me on a player that you’ve drafted. After you draft the player, he might say, “Well, I didn’t really say that.” I’d say, “Yeah, but your report indicates that.” “But I didn’t mean that.” The more you’re familiar with the people, the more that you work with them, the more secure you feel in dealing with them.

Scouting’s not easy. Some people can scout forever and never find a player. They just can’t do it. They’re just not cut out for it. Other people just fall into it. They just have that ability to do it. Jim Russo was a schoolteacher and I made him a part-time scout, and right away he was good. When I was with Kansas City, I needed a scout in New York/New Jersey. You’d like someone bilingual. I had Joe Torre’s dad working for me as a part-time scout. Gary Blaylock, a scout who’d been in the Yankees organization, said, “I have a buddy, a guy named Al Diaz. Pitched in the Yankees system, pitched Double-A, Triple-A. Bilingual. From New Jersey, I think. He’d be a hell of a scout up there for you.”

I said, “Where’s he living?” He said, “In Dubuque, Iowa, someplace. He’s working with the YMCA.” So I call him on the phone – I don’t even know the guy – I said, “Gary speaks so highly of you. Did you ever think of getting back into baseball?” “I’d love to get back into baseball.” I said, “Well, have you ever scouted?” He said, “No. But I can scout. I know that area pretty well.” “Would you be willing to take a two-year contract?” Never scouted. I put my neck out. Way out. We had to move him to New Jersey. The house he bought had a problem. Had to put him in a motel for three months and pick up his expenses for his family. He’s in the business for just one year and he said, “I think I’ve got a player who’s pretty good, at Iona College.” I said, “Iona’s a basketball school, not a baseball school.” “No,” he says. “I think I’ve got a player who’s pretty good. His name is Dennis Leonard. You better come see him.” I sent in three or four scouts. He obviously had a good arm. We take him number 1. He’s been scouting one year and he recommends him.

A year later he called me and said, “I’ve got a player. He’s going to go pretty high in the draft. His name is Willie Wilson. Summit, New Jersey, High School.” Stunning. He could have been a bust, but I had so much confidence in Blalock. Blalock really sold me on the guy. Diaz became a better and better scout. Sometimes you get lucky like that.

There’s no substitute for good scouting. You can’t see every player in the National League. If you’re going to make a trade, you can’t see every player in the league. You’re going to rely on your scouts. When I made the trade for Larry Andersen, the scouts said – Kasko and two others, Wayne Britton included – we think he’s the best setup guy in the National League. If you get him, you’ve got a hell of a good pitcher. We were down to one pitcher at the time. Unfortunately, we lose him because of the collusion thing. And we obviously misjudged Bagwell’s potential. But Andersen helped us win the division. We just couldn’t get by Oakland. Keep in mind that McGwire and Canseco are on that club. I think they hit between them 86 and 87 home runs and drove in about 240 runs. In the series, I think Canseco hit three home runs against us and McGwire hit two. Of course, Eckersley killed us in the bullpen.

Scouting is so important to you. The judgment is so important on the players that you’ve got. Particularly in Boston, it’s a little different playing here. This atmosphere is different here. I’ve been in Kansas City and Seattle, and it’s laid back there. Even St. Louis is more laid back. But this area, the intensity of the fans…they’re on top of you, the emotion is there, the passion is there. When you’re going good, they love you. When you’re going bad, you’ll hear it. Some guys don’t handle it too well. I think [Hanley] Ramirez last year [2005], I think that bothered him. I’m convinced it did.

He’s a better player. I know when they made the trade, I talked to Schuerholz, and I said, “Do you guys like Ramirez?” They said, “What did you think about him?” I said, “Well, I didn’t get to see him much because I don’t get to the dugout that much, but the few times I’d be down there for an on-field ceremony and sitting next to Francona, I’d see him come out and I’d say hello to him and talk to him. He looked like a very shy kid, like he needed someone to pat him on the back.” They said, “Lou, we love him. We don’t like him. We love him. We think he’s potentially going to be an All-Star shortstop.”

The pressure of playing here…the media can get on you pretty bad. The media can get very tough on you, and some players don’t react very well to that media thing.

Lou Gorman was interviewed by Bill Nowlin on September 5, 2006.