Memories of a Minor-League Traveler

This article was written by Norman Macht

This article was published in The National Pastime: Baseball in the Peach State (Atlanta, 2010)

Once upon a time in a faraway place—a place so far away no one under the age of sixty today has ever been there—there was a land called Organized Baseball, consisting of two major leagues of eight teams each and fifty-one minor leagues with names like Kitty, Pony, Cotton States, and Three-I. There were six levels of minors with teams in more than four hundred cities and towns. At the top was the AAA Pacific Coast League, which was just that: eight cities on the Pacific Coast. At the bottom were the Class D leagues—nineteen of them in towns such as Sweetwater, Pennington Gap, Donna-Robstown, Chickasha. The smallest town in OB-land was Landis, North Carolina, population 1,815. The ballpark was the high-school field.

Most of the lower-classification clubs were locally owned and operated. Many had working agreements with major-league organizations that provided the players and manager. But some were independent, scrounging for players as well as money. In 1951 I was the 21-year-old business manager of one such independent team, the Valley Rebels of the Class D Georgia–Alabama League. This is the story of how I got there and what I did there.

Legendary announcer Ernie Harwell got his start in the radio booth of Atlanta’s Ponce de Leon Park.

I arrived in Atlanta in the spring of 1948 at an age when the idea of conquering the world still seemed feasible. I knew only one person in the city, though I’d never met him. While a prewar student at Georgia Tech, my brother became friendly with the young sports director at radio station WSB (“Welcome South Brother”)—Ernie Harwell, who did a lot of interviews of present and past sports figures on his daily 15-minute show. After four years in the Marines, Harwell came home in 1946. Finding that WSB had cut back its sports coverage, he decided to go freelance and pursue his dream of becoming a play-by-play broadcaster. While stationed in Atlanta in 1943, he broadcast a few games for the Atlanta Crackers of the Southern Association (at that time, Class A-1) before the Corps put the kibosh on that activity. The club president, Earl Mann, welcomed him back in 1946, and he had been the voice of the Crackers ever since.

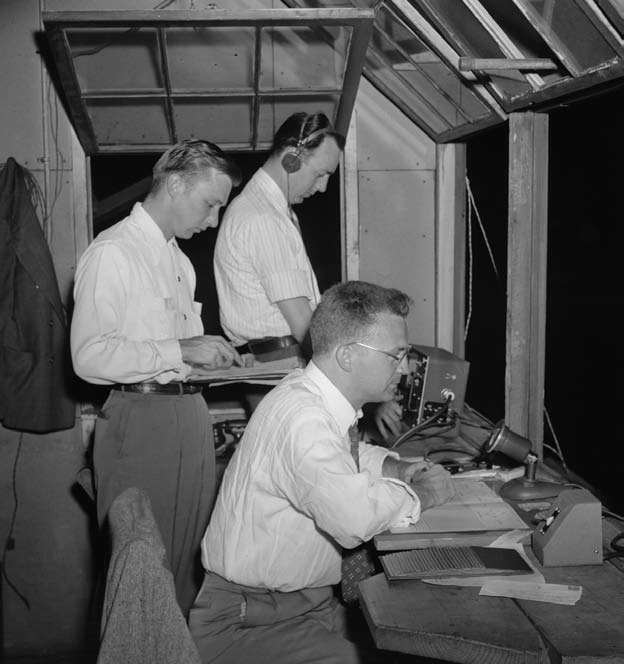

Ernie helped me get a job as a copywriter at the station that carried the games, WBGE (“Benton’s General Elevator”) and employed me as a gofer and statistician in the broadcast booth. There were no media staffs, no handouts with all the stats. We relied on newspapers and our own record-keeping. Before the game I went to the managers and picked up the lineups. I updated the batting averages and other basic, rudimentary stats of the time. After each Cracker time at bat during the game, I recalculated (by looking in a little book of batting-average calculations) the player’s numbers. The radio booth was separate from the press box. If there was a question for the official scorer or something about the rules or the past or a record, I went and got the answer. I brought Ernie the scores of other games in progress.

Broadcasters didn’t travel with the team. Road games were recreated sitting at a table in a small windowless studio in the basement of the Georgian Terrace Hotel. A Western Union operator sat across from us, an empty Prince Albert tobacco tin stuck between the key and the side of the wooden container to amplify the clickety taps. The operator, whom we knew only as “Buck,” typed the bare-bones result of each pitch and handed the slip of paper to Harwell, who had to bring it to life. Working a few batters behind the action, we got so we could recognize the sound of the brief clicks signifying a home run or double play to come. In the southern tradition, Harwell was a storyteller. He was long on stories and anecdotes, lean on stats-rattling. Stories have characters as well as action, but there were no media guides. During spring training and the first visits of the other teams to Atlanta, Ernie would go to the team hotel and talk to the players and coaches to learn their personal information: hometown, schools, family, hobbies, height and weight, off-season jobs— stuff he would refer to during the game that helped the listener know the players as individuals. Sometimes, when a new player joined a team between visits to Atlanta, I would gather that information for him.

An index card was made up for each player with his past records on one side and this personal info on the other. Ernie had designed a thin wooden case that opened flat. On each side was a place for the roster, lineups, scorecard, and defensive alignment for each team. Along each side were overlapping plastic sleeves for the index cards.

The delivery style that took him to the Hall of Fame was there from the beginning. I listen to an audition disc he cut in 1946 and a tape of an Orioles-Tigers game nearly fifty years later. He sounds the same. I knew Ernie for sixty-one years. He never changed. He wore like a pair of old slippers. He was completely unpretentious, easygoing, hospitable, courteous to everyone he met no matter who they were or their station in life. Even then, when I was a teenager, and throughout the next half-century, if he was with a group of broadcasters, writers, managers—whoever—and I appeared on the scene, he never failed to introduce me. In the 1980s and ’90s, when I was working in the Orioles’ press box and the Tigers were in town, I would bring friends into the tiny visitors’ broadcast booth to listen to him on the air; he treated them as if they were prospective sponsors. He never ate or drank anything while he was on the air. (I don’t think his weight varied a pound from the first time I saw him to the last.) Certainly his beret size never grew.

He was just as unflappable at home as he was on the air. He would sit in a wingback chair while his two little boys, Bill and Gray, would swing through the air from a trapeze bar secured high in a doorway behind him, and climb on or over him from the front or back, and he would carry on a conversation as though they didn’t exist. He was comfortable with a mike in his hands but not a hammer or screwdriver.

The April 1949 exhibition games featuring Jackie Robinson drew huge crowds.

Let me say here that no two finer people ever trod the earth than Ernie Harwell and his wife, Lulu. I had no place to stay when I first arrived in Atlanta in 1948. The Harwells kindly took me into their home until I found a rooming house near the ballpark. My stay with them was the most sleep-depriving experience of my life. It wasn’t their two little boys or a noisy neighborhood that kept me awake. My bed was in Ernie’s office, a room lined with bookshelves filled with baseball and other sports books and file cabinets stuffed with fascinating clippings on players past and present. What future SABR member could waste time sleeping in such surroundings?

It was the start of a friendship that continued all our lives. Later, when he was retired and writing a column for a Detroit newspaper, he would sometimes call me with a question about the old Crackers or Connie Mack or something he thought I might have researched. More often I would call him with questions about old-timers he may have met or interviewed. He always made me feel that he was glad I called.

In late July 1948, Brooklyn announcer Red Barber was hospitalized with a bleeding ulcer. Branch Rickey had had his eye on Harwell and called for him to come and fill in for Barber. The ad agency for the Crackers’ sponsor, Old Gold cigarettes (Ernie never smoked), was okay with it, because they sponsored the Dodgers’ games, too. The Crackers’ president, Earl Mann, wouldn’t stand in his way, but Mann wanted a player in exchange, a catcher at Montreal named Cliff Dapper. Mann wanted him to manage the Crackers in 1949; Rickey agreed. Dapper managed the Crackers for one year; and never again managed above Class B. Ernie Harwell was still broadcasting in the major leagues almost sixty years later.

But before Ernie left for Brooklyn, I had a job to do. He needed cards full of personal information on the 200 players in the National League—pronto. Back I went into his office for a few days and sleepless nights to turn them out. I requested as compensation a few books from his library. I still have them.

For the next two years, I worked for Harwell’s successor, Jim Woods, a native of Kansas City, who later broadcast in New York, Pittsburgh, Oakland, and Boston. Woods, who wasn’t known as “Possum” then, was a cat of a different cut from Ernie. He was more of a party person. He and Earl Mann became good buddies. He introduced me to bourbon and Coke, a drink I called “A Babe in the Woods.” Part of my job was to get the Coke, pour a little out of the bottle, pour in the bourbon (which he handed me), and shake it up. In the booth. On the air. It never affected his work. He was an outstanding play-by-play man—nothing folksy—with a deep resonant voice. There were no cards with player information. He had a phenomenal memory. Among other things, he could name every Kentucky Derby winner. Jim’s wife Ramona, a sweet lady, was a buyer at Rich’s department store. Later when I visited Jim when he was with the Yankees, he had a huge English bulldog named Bogey. I never saw Bogey move a muscle.

Another announcer, Les Hendrickson, did pre-game interviews. Les was a big man well over 6 feet tall and 200 pounds. On the field they were a colorful pair, Woods in a flamingo pink suit and Hendrickson in a creamed spinach outfit.

On Saturday afternoons we did a major-league game of the week from the subterranean studio at the radio station.

The Atlanta Crackers were an independent team backed by Coca-Cola; all the other clubs in the league were affiliated with big-league clubs. The president and general manager was Earl Mann, and the Crackers operated the old-fashioned way. They had their own full-time scout, Joe Pastor, and their own working agreements with lower clubs. They signed players, developed them, and sold them to the major leagues. The team was a mix of men on their way down (like Jim Bagby Jr.), young men on their way up (like Art Fowler, Davey Williams, and Gene Verble), and career AA minor leaguers like outfielder Ralph “Country” Brown, a fast left-handed batter who taught me the beauty of the drag bunt. Earl Mann hired his own managers, and Kiki Cuyler had been his manager since 1944.

The entire operation consisted of Mann and two other men in the office—Jasper Donaldson and John Stanton—plus a concessions manager named Raul Ovares and groundskeeper Howard Hubbard. That’s all.

Ponce de Leon Park was located in a light commercial pocket on Ponce de Leon Avenue surrounded by residential neighborhoods. The field was below street level. Railroad tracks ran behind the right-field embankment. A lone magnolia tree bloomed on the steep slope in right center field more than 400 feet from home plate, undisturbed by fly balls since Babe Ruth’s time until Eddie Mathews arrived in 1950.

It was there that I had my one brief meeting with Connie Mack on the afternoon of April 13, 1948. As I described in the preface to my Connie Mack biography, Atlanta was a regular stop for major-league clubs barnstorming north from spring training. The Athletics were in town for two games.

Connie Mack was sitting on a park bench in left field while his team took batting practice. I decided I’d like to meet him. He was 85. I was 18. I walked out and introduced myself and shook hands—I remember bony but not gnarled fingers—and sat down. I asked him something about some team that was in the news—it might have been a clubhouse fight or something of that nature. He answered politely, patiently, assuring me that whatever it was wouldn’t affect the team’s performance on the field. I asked him about this and that—an 18-year-old’s questions, devoid of any great insight or import. After a few minutes I thanked him for the opportunity to talk with him and took my leave. I had no idea that I would be writing his biography sixty years later.

I was there when Jackie Robinson made his first Atlanta appearance with the Dodgers April 8, 9, 10, 1949. The Dodgers had broken attendance records in Texas and Oklahoma the spring before, avoiding their usual southeastern stops. Before the Friday night game, the KKK Grand Dragon announced that 10,000 people had signed a petition to boycott Crackers’ games, threatening large financial losses to the club, if any black players appeared on the field with whites.

A typical Class D ballpark of the 1950s, home of the Valley Rebels of the Georgia–Alabama League.

Earl Mann ignored the threats. Anticipating a capacity crowd, he had the outfield roped off from left to where the right-field wall began. The ropes were needed; the Friday night opener attracted 15,119 fans, one-third of them blacks, overflowing the stands. Hundreds sat on the embankment or atop the three tiers of billboards between the fence and the railroad tracks. The Dodgers won, 6–3, and Robinson and Roy Campanella were cheered loudly for every step they took. Almost 9,000 turned out for the Saturday afternoon game, won by Atlanta, 9–1. There was no hint of what was to come on Sunday.

The estimated capacity of Ponce de Leon Park was between 12,500 and 15,500. In those days, blacks were restricted to the outfield bleachers. Imagine the scene, then, when 13,885 blacks bought tickets, just over half of the total paid attendance of 25,221, which far surpassed the previous record of 21,812 at the 1948 opener.1 Standing room in the outfield and in the grandstand was packed solid. The embankment was covered with more people than the total attendance would be at most games.

For many of the fans, the highlight of the game, won by the Crackers, 8–4, was Robinson’s steal of home on the front end of a double steal in the second inning. There were no fights, riots, or disturbances of any kind at any of the games.

In 1950, Earl Mann gave me a job in the office so I could learn the business. On the side I also worked for the Howe News Bureau as the stats-compiler for three Class D leagues. The official scorers sent me their score sheets—sometimes coffee- or mustard-stained, written over, reworked beyond legibility. A 16-inning, 12–11 game with eight pitchers was a nightmare; the rare 1–0 game was a joy. I updated each player’s and team’s stats as I received them, and once a week cut a stencil (you’re old if you remember stencils) for each league, ran them off on the ink drum, and mailed them out to subscribers. I also brought the stats for the Southern Association’s top hitters and pitchers up to date each day and turned them in to the two Atlanta newspapers.

That was the year the Crackers signed a working agreement with the Boston Braves that brought them then 18-year-old Eddie Mathews, making the jump from Class D, where he’d hit .363. The Braves also supplied Bob Thorpe, Don Liddle, and Ebba St. Claire. Among the veterans were Ellis Clary, Hugh Casey in the last year of his life, and the perennial Atlanta favorite, Country Brown. The manager was Dixie Walker; the coach was Whitlow Wyatt.

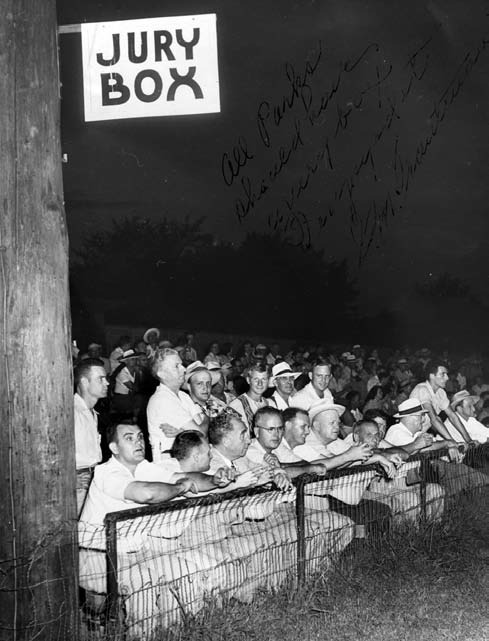

The jury box was a section behind third base at Jennings Field reserved for the most vocal fans. When George Trautman, president of the Minor Leagues, visited in August 1951, he insisted on sitting there. Trautman, third from the left in the front row, inscribed this photo: “All parks should have a jury box. I enjoyed it.”

Mathews, with 32 home runs and 106 RBIs, led the Crackers to the pennant. Earl Mann allowed me to go with the team to Nashville for the playoff series. After the last game Whitlow Wyatt, who had driven there, invited me to go back to Atlanta with him. The Georgia native was the epitome of a courtly southern gentleman, but I had had it in for him ever since he dusted off my hero Joe DiMaggio, touching off a brawl in the fifth game of the 1941 World Series. When I confessed my grudge, he laughed it off. By the end of the ride, I had forgiven him.

Toward the end of the season, I heard a team in the Georgia–Alabama League was looking for a business manager for 1951. The league had teams in Rome, Griffin, and LaGrange in Georgia; Opelika and Alexander City in Alabama; and the Valley Rebels, who straddled the border and the Chattahoochee River. The Valley consisted of five West Point-Pepperell textile towns: West Point, Georgia, and Lanett, Langdale, Fairfax, and Shawmut in Alabama. The population was about 15,000 to 20,000.

Jennings Field was in Lanett. Named for 77- year-old Robert Jennings, known as the Dean of Valley Sportsmen, it resembled the ballpark in “Bull Durham”— wooden grandstand, small bleachers from home to first and third, a capacity of about 3,500.

The mills sponsored the team. I was interviewed and hired by the club president, Robert Rearden, manager of the Langdale Mill. Our public-address announcer was his son-in-law, a fact I did not know when I became dissatisfied with his performance and fired him. I was quickly “advised” to reverse that decision—advice I heeded.

For the previous two seasons the Rebels had had a working agreement with the Red Sox, but no longer. LaGrange was the only team with a major-league affiliation—the Yankees. We were on our own to round up players as best we could. In the end, 25 players came and went. Only one of them would ever set foot on a triple-A field, leaving no footprints. The manager, a veteran minor-league catcher named Perley “Gabby” Grant, signed up some of his friends, including 30-something semi-pros who were technically rookies in OB. Our first baseman, Mal Morgan, worked in one of the mills while playing every summer for the Rebels. Several of them put in five to eight years playing Class D ball, a breed that has been made extinct by baseball evolution.

And some were kids, like 18-year-old Gene Black, a big right-hander who won 10 games and pitched a no-hitter against LaGrange one night, the pinnacle of his brief career.

The “front office” was a one-man operation— me. Everything the staff of a minor-league club does today, I did. Everything: player transaction paperwork, promotions, selling ads for the outfield fence and scorecards, making speeches, hiring the ticket seller, stocking concession stands, counting the sticky dimes from the sno-cone stand after the game. My wife sold the scorecards and was my best PR asset.

An old man, Isham Corley, was the groundskeeper. He had been there for thirty years, through two previous incarnations of the league. I don’t remember if he was a county or a mill employee; perhaps I never knew.

For the past few years the Rebels had averaged under a thousand a game in attendance. I tried every corny promotion I could put together. On the afternoon of opening day, the players rode on a West Point fire engine, preceded by the high-school band, in a parade through the Valley. I climbed into a little two-seater Piper Cub and flew over the towns, one hand holding open the door and the other tossing out flyers promoting the game, while the plane dipped and swooped. Fortunately, I went up on an empty stomach; when we landed I was as green as the outfield grass.

There were prizes every night for lucky scorecard numbers: pens, lamps, dishes, radios, little ballplayer pins, even a television set. We had a cow-milking contest for the players, crowned a Miss Valley Rebel, and elected a Number One fan, whose prize turned out to be the least-valuable prize ever won—a lifetime pass to the Rebels’ games.

We had kids’ nights that drew over 200 youngsters free and brought almost 700 paid adults through the gates—and greatly increased the concessions sales. After June 30th all kids wearing a $1 Valley Rebel T-shirt came in free to all games. Fat Man’s Night (remember this was 1951) admitted free anyone denting the scale at the gate for more than 200 pounds; 85 qualified. An old-timers game between the Rebels and local diamond heroes of yore drew 913.

We were in first place on July 4th and hosted the league all-star game, but the league was already on life support. Our attendance was averaging about 600, a little more than half of what it would take to break even. At that, we were drawing better than anybody else in the league, except maybe Rome, a city of about 30,000.

By then, Opelika had thrown in the Cannon towel, and 10 days later Alexander City would do the same. So the league directors split the season. Griffin won the first half by a game over LaGrange and us. LaGrange won the second half. There were no playoffs.

In May I had set out to break the single-game attendance record for a Class D club. But the National Association had no idea what the record was. They received attendance reports by leagues, not individual clubs. I went ahead anyhow and launched a three-month campaign of advance sales. The target game was August 16.

On August 14th National Association president George M. Trautman came to the Valley and sat in our “Jury Box,” a section of the third-base bleachers I had set aside for a bunch of regulars who were the most vocal riders of players and umpires. A photo of Trautman in the Jury Box ran in The Sporting News on August 29, 1951. Two nights later our “record-breaker” didn’t break any records that we knew of, but we did sell 2,428 tickets. The season—and my job—ended on August 25. The Georgia-Alabama League never saw another season.

Then there was a fracas in Korea, and I spent the next four years working in the farm system of the U. S. Air Force. When I came out of the service in 1956, I became the business manager of the Milwaukee Braves’ Class C farm at Eau Claire, Wisconsin, in the Northern League for two years. That’s where my friendship began with Roland Hemond, who worked in the Braves’ minor-league office. During the season I hosted a weekly 15-minute TV show, “Let’s Talk Baseball,” featuring a different player each week. One of those players was a fast-talking, sharp-dressing, .171-hitting catcher, Bob Uecker. (He improved to .284 the next year.) In 1958, I moved to the Knoxville Smokies in the Class A Sally League. By 1959 I realized that moving up the ladder to the major leagues meant constantly moving from one rented apartment and city to another, something I had been doing between the service and baseball for the last eight years. I was no longer a boy wonder. And the opportunities had shrunk. Minor-league baseball had been hit by the spread of major-league radio and television broadcasts. Expanded television programming and the increased availability of home air conditioning kept people at home during cold April and hot mid-summer evenings. Whereas fifty-one minor leagues operated in 1951, only twenty-one opened the season in 1959.

My baseball travels were over. I’m glad I made them.

NORMAN L. MACHT has been a SABR member since 1985. He is currently living in 1934 in volume 2 of his biography of Connie Mack.

Notes

1 New York Times, 11 April 1949.