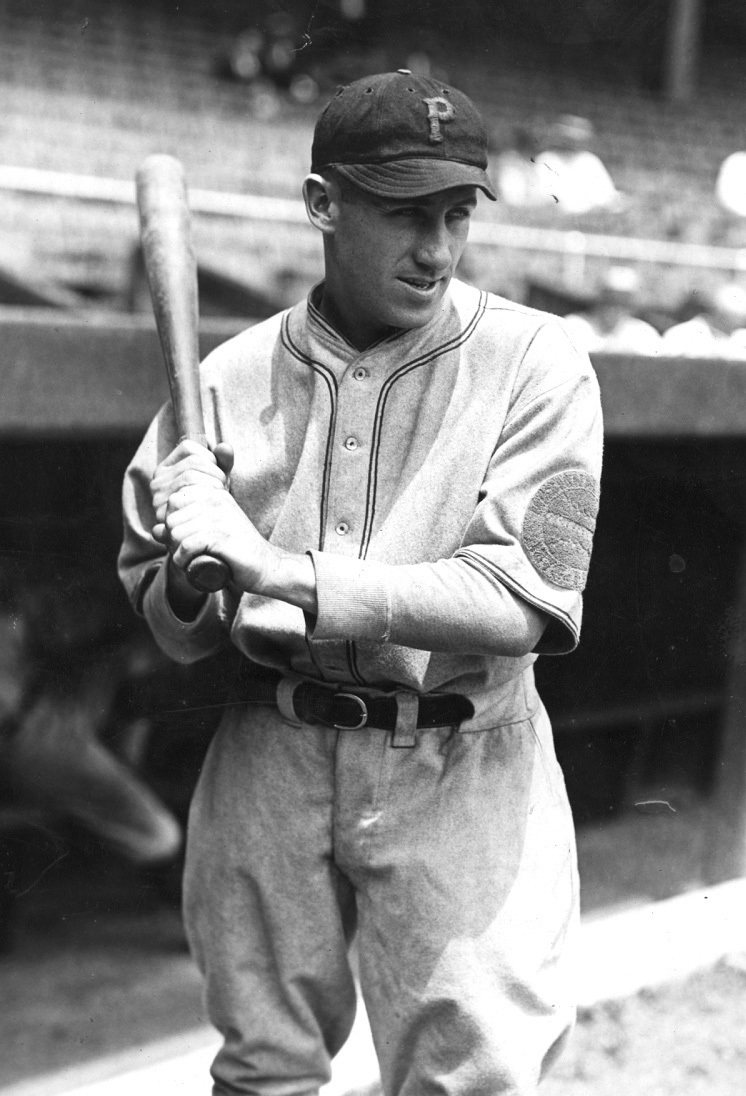

Kiki Cuyler

Though contemporary newspaper reports typically referred to Hall of Fame outfielder Hazen Cuyler by his given name, the right-hander is more easily recognized by one of the most unique, yet most often mispronounced nicknames in baseball history: Kiki. “It came from shortening my name,” Cuyler explained about acquiring the moniker (which rhymes with “eye-eye”) as a minor leaguer in 1923. “Every time I went after a fly ball, the shortstop would holler ‘Cuy’ and the second baseman would echo ‘Cuy’ and pretty soon the fans were shouting ‘Cuy Cuy.’ The papers shortened it ‘Kiki.’”1 According to another story, the sobriquet had less glamorous origins: It arose as a way to mock Cuyler, who struggled to overcome his stuttering.

Cuyler had been dead for almost two decades and his accomplishments had largely faded with memory when the Veterans Committee elected him to the Baseball Hall of Fame in 1968. But during his heyday in the mid-1920s through mid-1930s with the pennant-winning Pittsburgh Pirates and Chicago Cubs, Cuyler was considered one of the most popular and most exciting players in baseball. Blessed with uncanny speed, quick reflexes, and a powerful arm, Cuyler was a solid line-drive hitter with surprising power. In an 18-year career (1921-1938) that was also marred by injuries and an enduring controversy with a manager, he batted .321, collected 2,299 hits, led the major leagues in stolen bases four times, and had a legacy-defining, Series-winning hit in Game Seven of the 1925 World Series for the Pirates.

Hazen Shirley Cuyler was born on August 30, 1898, in Sturgeon Point, a small village in northeast Michigan on the coast of Lake Huron. Cuyler’s Canadian-born parents, George Alonzo and Anna Rosalind (Shirley) Cuyler, married in 1891 and were naturalized as US citizens in 1895, about three years after their first child, Edna, was born. While Anna found piecemeal work as a dressmaker, George, a former semipro baseball player, served in a local coast guard, the Life Saving Service of Sturgeon Point. He suffered an injury in the line of duty in 1906, prompting the family to relocate five miles to the south, to Harrisville, where he became a respected public servant. “Cuy,” as Cuyler was known to his friends and family, was an active youth who enjoyed fishing and hunting, and an all-around athlete. By the age of 14 he was playing baseball in local sandlot and semipro leagues. At Harrisville High School he played baseball, basketball, and football, and ran track. He graduated in 1917 as the valedictorian of his class of five students. After finishing high school he enlisted in the US Army and served in Company A of the 48th Infantry Regiment, but was not sent to France during World War I. He briefly attended the US Military Academy at West Point before returning to Michigan and marrying his high-school sweetheart, Bertha M. Kelly, in 1919.

Cuyler and his young bride (soon to be joined by their first child, Harold) moved to Flint, Michigan, where Cuyler worked in a Buick factory and carved out a reputation as a hard-throwing right-handed pitcher in competitive industrial leagues in Flint and Detroit, about 70 miles south. According to Ronald T. Waldo in his informative biography of the player, George H. Maines, president of the Class B Michigan-Ontario League, signed Cuyler to a contract for the Bay City (Michigan) Wolves in 1920.2 When Cuyler was spiked while sliding into second base, Wolves manager Calvin Wenger moved him permanently to the outfield. During the season Cuyler batted .258 in 69 games.

With a vastly improved batting average in his second season (.317), Cuyler attracted the attention of big-league clubs. Ty Cobb, in his first year as player-manager of the Detroit Tigers, wanted to sign the local star; however, the Tigers’ owner, Frank Navin, refused. Undeterred by reports that Cuyler had difficulty hitting a curveball, the Pittsburgh Pirates, acting on the recommendation of scout Frank Haller, purchased the speedy outfielder for an estimated $2,500.

A gifted yet green prospect, Cuyler needed to prove he could hit big-league pitchers. After the Michigan-Ontario League playoffs, the Pirates called up Cuyler in September 1921. He made his major-league debut on September 29, starting in right field in the second game of a doubleheader against the St. Louis Cardinals, going 0-for-3 in the 5½-inning contest. He had to wait nearly a year to get into another major-league game, and then appeared in only one, as a ninth-inning pinch-runner.

Cuyler was optioned to the minors for more seasoning after participating in spring training in 1922 and 1923. He batted .309 for the Charleston (South Carolina) Pals, champions of the Class B Sally League, in 1922, followed by his breakout season with the Nashville Volunteers of the Class A Southern Association. Named the league’s most valuable player, Cuyler, whom fans and sportswriters had begun calling “Kiki,” led the circuit in runs scored (114) and stolen bases (63) while batting .340. Cuyler attributed his hitting success to a decision to stand deep in the batter’s box. In his third consecutive late-season call-up with the Pirates, Cuyler rapped five hits in his last 11 chances to finish with a .250 average in 40 at-bats.

A perennial first-division team, the Pirates got off to a slow start in 1924 in their quest to unseat the three-time NL pennant-winning New York Giants. Cuyler had played primarily center field in the minors, but that position belonged to veteran Max Carey, long acknowledged as the best basestealer and one of the fastest players in the NL. Relegated to the bench as the season started, Cuyler went 3-for-4 with a double and triple in his first start of the year, on May 6, en route to collecting 11 hits in 17 at-bats in the first four games he started, and he worked himself into batting third in the regular lineup.

By early June Cuyler had replaced the slumping veteran Clyde Barnhart in right field. In early July he was moved to left field in place of the struggling Carson Bigbee. He collected six hits, including three doubles and a triple, in the Pirates’ 16-4 drubbing of the Philadelphia Phillies on August 9 during the first game of a doubleheader. “Cuyler has had much to do with the success of the Pirates,” wrote Pittsburgh beat reporter Ralph. S. Davis. “[He’s] won a place in the heart of Pittsburgh fans.”3 In the Pirates’ doubleheader sweep of the St. Louis Cardinals on September 6, Cuyler homered in each contest and drove in a total of six runs, raising his batting average to .380, to keep the Pirates just one game behind the league-leading Giants and a half-game behind the Brooklyn Robins in a tight three-team pennant race.

The Sporting News described Cuyler’s rise to stardom as “meteoric” and compared his aggressive hitting to that of Rogers Hornsby. But Cuyler, suffering from a sore right shoulder, slumped in September, batting .211 in 17 games beginning September 7. His season came to a premature end on September 25 after a crushing three-game series sweep by the Giants at the Polo Grounds. Almost universally praised as “one of the season’s sensations,”4 Cuyler easily led the Pirates in batting (.354, fourth best in the NL) and home runs (9) while scoring 94 runs and rapping 16 triples in just 117 games.

Despite the success in his rookie campaign, Cuyler began his sophomore season under pressure to prove that he was not a “flash” and that his late-season slump was merely an aberration. Though the Pirates started the season poorly again, occupying last place as late as May 9, Cuyler re-emerged as the offensive catalyst for the club. On June 4 he hit for the cycle for the only time in his major-league career and drove in three runs in the Pirates’ 16-3 throttling of the Philadelphia Phillies in Forbes Field. He experienced a career day on June 20, belting two home runs for the first of three times that season (and five times in his career), driving in a personal-best six runs, and tying a career high with five runs scored in Pittsburgh’s 21-5 victory over the Brooklyn Robins in the Smoky City. Continuing his relentless hitting, Cuyler guided the Pirates to a 55-32 record from July through September as they captured the pennant by 8½ games over the Giants. Described by The Sporting News as “closing the season in a blaze of glory,”5 Cuyler tied an NL record by collecting ten consecutive hits over three games September 18-21, and then went 4-for-4 on September 22, giving him 14 hits in 16 at-bats. Syndicated sportswriter Norman E. Brown compared Cuyler to the Pirates’ 35-year-old center-fielder, Max Carey (en route to leading the NL in stolen bases for the tenth and final time in 13 seasons). Carey tutored the youngster in the finer points of baserunning, including sliding technique and avoiding pickoff attempts. After swiping 32 bases in 1924, the “Flint Flash” was successful on 41 of 54 attempts in 1925, and then led the major leagues in stolen bases in four of the next five seasons. In one of the most prolific seasons in Pirates history, Cuyler set a post-1900 NL record with 144 runs scored, led the majors with 26 triples among his 220 hits, clouted a career-best 18 home runs, and finished fourth in batting average (.357). His 369 total bases still rank as the most in Pirates history (as of 2024). Cuyler finished second in the NL MVP race to the Cardinals’ Rogers Hornsby.

Cuyler’s clutch hitting helped propel the Pirates to victory over the reigning champion Washington Senators in the 1925 World Series. After Pittsburgh lost Game One to Walter Johnson at home, Cuyler belted a game-winning two-run homer off starter Stan Coveleski in the eighth inning of Game Two to give the Pirates a 3-2 victory. Losses in Games Three and Four left them down three games to one, but the Pirates battled back to force a Game Seven, which the Associated Press at the time described as “perhaps the most thrilling seen in World Series history.”6 In a “rain-soaked, furious dramatic struggle” at Forbes Field, Cuyler came to bat with the bases loaded against Walter Johnson in the bottom of the eighth inning with the game tied, 7-7.7 He hit what appeared to be a home run down the right-field foul line; however, the ball dropped in the outfield, buried itself in a tarpaulin, and was ruled a ground-rule two-run double. It gave the Pirates a 9-7 lead, and the championship.

With the offseason acquisition of hitting phenom Paul Waner, a center fielder, from the San Francisco Seals of the Pacific Coast League, the Pirates were expected to duplicate their success of the previous season; however, the 1926 season devolved into one of the most disappointing and acrimonious in Pirates history. In light of his World Series heroics, Cuyler held out for more money, and his ensuing wrangle with Pirates owner Barney Dreyfuss played out in the papers before Cuyler signed a contract. After a slow start, he batted .449 (53-for-118), scored 25 runs, and knocked in the same number over a 28-game span to raise his average to a league-leading .381 on June 11.

On July 26 the Pirates took sole possession of first place and seemed destined to claim another pennant. The turning point in the season came to be known as the ABC affair. The controversy started when Pirates vice president Fred Clarke, who was sitting on the bench and acting in the role of assistant coach, made disparaging remarks about Max Carey, who was struggling uncharacteristically with a .214 batting average, and demanded that manager Bill McKechnie replace him during a doubleheader shutout loss on August 7 to the seventh-place Braves at Boston. Veterans Babe Adams, Carson Bigbee, and Carey held a team meeting to decide whether Clarke should be allowed to remain on the bench. On August 13 Pirates brass quashed the insurrection by releasing all three players; however, the damage had been done. Pittsburgh limped to a 23-24 record and a third-place finish after the players were released. The tensions in the team clubhouse seemed to affect Cuyler, too. In his final 51 games after the initial brouhaha, he seemed at times indifferent, batted just.288, and drove in only 21 runs. Cuyler led the league in games played (157), runs (113), and stolen bases (35); however, critics pointed to his lower batting average (.321) and drop in home runs (18 to 8) and RBIs (102 to 92) as evidence of a poor season.

Donie Bush replaced McKechnie as manager of the Pirates in 1927 and vowed to run a more disciplined ship. Rekindling his aggressive approach, Cuyler was batting. 329 for the first-place Pirates on May 28 when he tore ligaments in his ankle sliding into third. During the weeks after he returned to the lineup on July 9, tensions between the player and his manager flared, resulting in one of the most enduring mysteries in Pirates history. Not only upset that he was moved from center field to right field, Cuyler objected to batting fifth and especially second, instead of his customary third position.

The situation came to a head when Cuyler failed to slide during a force play at second base in a game against the New York Giants on August 6, earning him a $50 fine. The controversy became a national story when Cuyler was subsequently benched and started only one game for the remainder of the season even though the Pirates were battling for the pennant. The Sporting News reported that Dreyfuss instituted the benching because he still fumed over the player’s holdout after the 1925 season; others countered that the player was moody and egotistical, and wanted more publicity.8 The fans, however, were unanimous in their desire to see Cuyler on the field. Even without Cuyler, the Pirates captured the pennant and faced the New York Yankees in the fall classic. “The ‘Cuyler Case,’” wrote Ralph S. Davis, “almost overshadowed interest in the World Series.”9 While theories for his benching and rumors of his trade swirled, Cuyler did not play in the Series, and the Pirates were swept in four games by the Bronx Bombers. Other than a few superficial remarks, neither Dreyfuss, Bush, nor Cuyler ever publicly discussed the behind-the-scenes machinations of the controversy.

While Cuyler’s departure from Pittsburgh was a foregone conclusion, it was a surprise on November 28, 1927, when the Chicago Cubs acquired the player in exchange for infielder Sparky Adams and outfielder Pete Scott. The Sporting News quickly dubbed Riggs Stephenson, Hack Wilson, and Cuyler as the “best fly chasing trio in baseball,” and predicted that Cuyler’s arrival “will tip the scales in favor of the Cubs” in the pennant race.10 With an exceptional spring training, Cuyler eased worries that he was a self-absorbed player or, worse, a troublemaker. Cubs manager Joe McCarthy boasted, “I’ve got the best hitting outfield in the National League,” fueling expectations that Cuyler would duplicate his success from 1925 and 1926.11 In a preseason exhibition game in Kansas City, Cuyler seriously injured his right hand when he ran into a wall attempting to catch a fly ball. The injury, which made it difficult to hold a bat, plagued the outfielder the entire season, and contributed to his poor start. Furthermore, he was an aggressive, first-pitch hitter and had difficulty adjusting to McCarthy’s approach of taking pitches when ahead in the count. Batting third and playing right field, Cuyler was hitting just .206 on June 11, and his season appeared to be a washout. However, he surged in his last 49 games, batting .338 and scoring 39 runs. Cuyler led the major leagues with 37 stolen bases and the team with 92 runs, offsetting a disappointing .285 batting average.

With the Cubs’ offseason acquisition of Rogers Hornsby from the Boston Braves, many experts picked them to take the pennant in 1929. Chicago boasted one of the most imposing lineups in NL history with Cuyler, Hornsby, Wilson, and Stephenson batting third through sixth. The quartet, affectionately called Murderers’ Row, collectively batted.362, belted 110 home runs, drove in 520 runs, and scored 493.12 Other than a leg injury that limited him to pinch-hitting duties for three weeks in July, Cuyler enjoyed relatively good health all season and excelled in an environment where the national spotlight focused on Hornsby and Wilson. “There was never a more valuable team player,” said McCarthy.13 A hallmark of consistency, Cuyler surged over the last 55 games of the season (he batted .396, scored 51 runs, and knocked in 48) as the Cubs built an insurmountable lead over the Pittsburgh Pirates to capture their first pennant since 1918. No player in the NL could match Cuyler’s unique combination of speed and power. He batted a career-best .360, led the majors with 43 stolen bases, mashed 15 home runs, and drove in 102 runs.

In their highly anticipated matchup with the Philadelphia Athletics, the Cubs lost Games One and Two at Wrigley Field. Cuyler, who struck out five times and managed just one hit, was roundly castigated as a “goat.”14 With the score tied, 1-1, in the sixth inning of Game Three, Cuyler “whistled a single through the box and out to centre [center field],” driving in Woody English and Hornsby to give the Cubs the lead and eventual victory.15 In Game Four Cuyler connected for three singles and drove in two runs. In Game Five he collected his first extra-base hit of the Series (a double). But the Cubs lost both games in monumental fashion. The A’s overcame an eight-run deficit by scoring a series-record ten runs (tied in 1968) in the seventh inning of Game Four, and then staged another dramatic comeback in Game Five when they scored three runs in the bottom of the ninth inning to capture the title.

In an era when many ballplayers were considered uncouth for their excessiveness off the field, Cuyler was an exception. Often described as one of the “gentlemen of baseball,” he neither drank nor smoke, and rarely argued with umpires or opposing players.16 Standing 5-feet-10½ and weighing a trim 175 pounds, Cuyler was good-looking, with wavy, dark hair and dark, penetrating eyes. Sportswriter J.T. Meek called him the “game’s fashion plate” and an “exponent of diamond neatness.”17 Cuyler kept his svelte figure by playing sports year-round. He resided in the offseason with his wife and two children (daughter Kelly June was born in 1928) in Harrisville, and played in nascent professional basketball leagues. He led his various teams on barnstorming tours to Pittsburgh and Chicago (among other cities) to capitalize on his notoriety and publicize the emerging sport. His interests included hunting and fishing, but also the arts. He was an accomplished dancer who frequently won waltz tournaments at the Cubs’ spring training site in Catalina Island. Blessed with a fine voice, Cuyler enjoyed singing, and not just in the clubhouse showers. He spent four weeks in 1930 on a vaudeville stage in Chicago with teammates Wilson, Gabby Hartnett, and Cliff Heathcote.18

The Cubs’ title aspirations were dashed when they lost the reigning National League MVP, Rogers Hornsby to a broken ankle in late May 1930, but Cuyler assumed a greater role in the Cubs’ offensive juggernaut, which set a franchise record by scoring 998 runs in the “Year of the Hitter.” Over a 13-game stretch beginning on June 23, Cuyler batted .483 (28-for-58), scored 17 times, and drove in an eye-popping 27 runs to help the Cubs transform a 2½-game deficit into a 1½-game lead in the pennant race. “So accustomed are the fans to watching this fellow burn up the bases,” wrote The Sporting News, “that it goes almost unnoticed with his constant hitting, running, fielding, and throwing.”19 Behind the hitting of Cuyler, Woody English (152 runs scored, 214 hits, .335 average), and the record-setting slugging of Hack Wilson (56 home runs, 191 runs batted in, .356 average), the Cubs increased their lead to 5½ games by August 30 and seemed poised for another NL pennant. “Cuyler’s brilliant work and the ‘never say die spirit’ of the team are reasons why the Cubs hold first place,” reported the Chicago Daily Tribune. But on August 31 they began an epic collapse by losing 14 of 21 games leading to finger-pointing and McCarthy’s ouster with just four games remaining. Hornsby, who had been jockeying behind the scenes for the managerial position, took the reins of the team for the final four games. In a dramatic and disappointing season, Cuyler played in all 156 of the team’s games (the third time he led or co-led the league in games played), scored 155 runs (tied for 24th-most in big-league history as of 2014), set career highs in hits (228), doubles (50), and RBIs (134), and led the major leagues in stolen bases with 37.

A five-tool player, Cuyler drew comparisons to Ty Cobb, Tris Speaker, and Shoeless Joe Jackson. Veteran Cubs scout Jack Doyle considered Cuyler the “most graceful player of all time, a fellow who could do more things with a glove than Cobb, who could throw better than Cobb, who could pick up groundballs on his outfield patrol like grounders.”20 Cuyler played all three outfield positions equally well; his strong arm made him an ideal right fielder and his speed was invaluable as a center fielder. Six times he ranked among the top five in assists for outfielders. “There is no center fielder who runs farther for long fly hits,” opined syndicated sportswriter John B. Foster.21

Ironically Cuyler’s athleticism, seemingly effortless play, and gentlemanly persona also drew criticism. “Cuyler had only one flaw that kept him from being rated with the immortals of the game,” suggested The Sporting News in his obituary, echoing sentiments heard throughout the player’s career. “He lacked the ruthlessness that might have carried him to greater heights and made his record even more brilliant.”22 Considered sensitive to criticism, Cuyler responded best to players’ managers, like McKechnie and McCarthy, instead of authoritarian types (Bush and Hornsby).

Cuyler proved to be one of the few bright spots in the Cubs’ mediocre and inconsistent season in 1931, during which players bristled at Hornsby’s autocratic managerial methods. Batting leadoff through most of June, Cuyler was moved back to the third spot to provide the team with more offense in light of Wilson’s precipitous drop in power (13 home runs). He batted .330, tied for third in the league with 202 hits, and ranked fourth by scoring 110 runs.

Cuyler’s reputation as one of the fastest players in baseball ended after he suffered serious injuries in 1932 and 1933. While rounding third base on April 24, 1932, Cuyler cracked a bone in his left foot and missed six weeks. Robbed of his ability to take an extra base, Cuyler struggled after his return on June 8. In a weak year in the NL, the Cubs occupied first place for much of May and June, but the season was careening out of control. Players were increasingly resentful of the tyrannical Hornsby, who was also under investigation by Commissioner Kenesaw Mountain Landis because of his gambling debts. On July 6 starting shortstop Billy Jurges was shot twice by showgirl Violet Popovich Valli (Jurges survived). In an odd twist, Valli blamed her actions on Cuyler, who had apparently tried to persuade Jurges to end the sordid affair. The Cubs began a miraculous transformation when affable first baseman Charlie Grimm replaced Hornsby as manager on August 4. The Cubs responded by winning 23 of their first 27 games under “Jolly Cholly” and cruised to an unlikely pennant. Cuyler surged under his former Pittsburgh teammate (.373 average with 28 RBIs in the last 28 games) to finish with a .291 average and 77 RBIs in 110 games.

In the World Series the Cubs lost four straight games to the overwhelmingly favorite New York Yankees, led by Joe McCarthy. There were few Cubs highlights in a Series best remembered for Babe Ruth’s supposed “called shot” in Game Three. In that dramatic contest, Cuyler went 3-for-4 with a double and solo home run to deep right field, but was otherwise quiet (5-for-18).

In 16 World Series games, Cuyler batted .281 (18-for-64), scored nine runs, and knocked in 12.

Cuyler splintered the fibula bone in his right leg during a spring-training game in 1933 and was limited to just 70 games (batting .317) for the third-place Cubs. While the rumor mill churned out reports of Cuyler’s trade to the Cincinnati Reds in the offseason, he reported to spring training in 1934 with his status as a starter in doubt. Cuyler’s productive spring enabled Grimm to juggle his outfield, moving offseason acquisition and reigning NL Triple Crown winner Chuck Klein to left field, inserting Cuyler in center, and keeping strong-armed Babe Herman in right field. While the Cubs contended for the title most of the season before finishing in third place, the 35-year-old Cuyler made a remarkable comeback. He ranked third in hitting (.338) and led the league with 42 doubles, and his 15 stolen bases trailed only St. Louis’s Pepper Martin’s 23. In the second year of the midsummer classic, Cuyler was named to his first and only All-Star team. Starting in right field, he went 0-for-2.

The Cubs caused a “minor sensation” when they released Cuyler (batting.268) on July 3, 1935.23 The Cincinnati Reds outbid at least five other teams to sign the aging star. On July 11 Cuyler debuted for the Reds as their center fielder. While the Cubs won 21 consecutive games in September to capture an unlikely pennant, Cuyler played on a losing team for the first time in his big-league career, and batted just .251 for the Reds.

The oldest regularly starting position player in the NL, Cuyler made yet another comeback in 1936. After batting primarily in the leadoff position through May, he went back to his customary third spot and hit at a .345 clip from June 4 on. He celebrated his 38th birthday by going 5-for-9 with two triples in the Reds’ doubleheader sweep of the Philadelphia Phillies at Crosley Field on August 30. He led the fifth-place Reds in hits (185), extra-base hits (47), runs (96), and RBIs (74), and batted .326.

During the Reds’ youth movement in spring training 1937, Cuyler suffered a broken cheekbone when he collided with Cincinnati second baseman Alex Kampouris during an exhibition game against the Detroit Tigers on April 1. Though he was ready to play by Opening Day, Cuyler revealed that the injury bothered his timing all season long. He batted just .271 with no homers and 32 RBIs for the NL cellar-dwellers. On September 21 he announced that he was retiring at the end of the season, and was granted his release on October 4.

A student of the game, Cuyler had long made it known that he wanted to transition into managing. After considering several minor-league managerial positions, he surprisingly signed with the Brooklyn Dodgers as a player on February 2 with the hope of moving into a coaching position that season. The NL’s oldest player, Cuyler started 58 games in the outfield and tutored a trio of 20-something flychasers — Buddy Hassett, Ernie Koy, and Goody Rosen. Cuyler was released as a player on September 16 and re-signed as a coach for the remainder of the season.24

A respected teacher, Cuyler spent his final 11 years in the dugout of minor- and major-league teams, but never achieved his dream of piloting a big-league club. Less than three months after retiring as an active big leaguer, Cuyler accepted a position as player-manager of Chattanooga in the Class A1 Southern Association. In his rookie season, he led the Lookouts to the pennant. He resigned after 2½ seasons with the club to accept a coaching position with the Chicago Cubs, serving under manager Jimmie Wilson through the 1943 season. Cuyler piloted the unaffiliated Atlanta Crackers of the Southern Association for five seasons (1944-1948), guiding them to first-place finishes in his first three years and to the league title in 1946. He spent his final year in baseball (1949) as a member of Joe McCarthy’s coaching staff for the Boston Red Sox.

Cuyler suffered a heart attack on February 2, 1950, while ice fishing near his home in Harrisville. Two days later, while he was in a local hospital, a blood clot formed in his leg. The likely cause was varicose veins, which plagued Cuyler his later years.25 When the situation worsened, he was sent by ambulance to a hospital in Ann Arbor but died in transit on February 11 at the age of 51. His funeral service was held on February 14 at St. Anne’s Catholic Church in Harrisville, and he was buried in St. Anne’s Cemetery.

Last revised: December 1, 2021 (ghw)

Sources

Ancestry.com

BaseballLibrary.com

Baseball-Reference.com

Chicago Daily Tribune

New York Times

Pittsburgh Press

Pittsburgh Post-Gazette

Retrosheet.com

SABR.org

The Sporting News

Hazen “Kiki” Cuyler player file from the Baseball Hall of Fame, Cooperstown, New York.

Notes

1 The Sporting News, February 10, 1968, 18.

2 Ronald T. Waldo, Hazen “Kiki” Cuyler. A Baseball Biography (Jefferson, North Carolina: McFarland, 2012) 14.

3 The Sporting News, July 24, 2.

4 The Sporting News, August 7, 1924, 1.

5 The Sporting News, October 1, 1925, 1.

6 Associated Press, “Pittsburgh Defeats Washington, 9-7, to Win World’s Baseball Championship,” Berkeley (California) Daily Gazette, October 15, 1925, 1.

7 Associated Press, “Pirates Win Seventh Game and World’s Championship,” Scranton (Pennsylvania) Republic, October 16, 1925, 1.

8 The Sporting News, August 18, 1927,1.

9 The Sporting News, October 20, 1927, 1.

10 The Sporting News, February 9, 1928, and March 1, 1928, 3.

11 John B. Foster, “Kiki To Play in Right Field, Latest Plan Of Cubs,” Pittsburgh Post-Gazette, March 8, 1928, 15.

12 The term Murderers’ Row is most readily associated with the 1927 New York Yankees, and Babe Ruth, Lou Gehrig, Bob Meusel, and Tony Lazzeri, who batted three through eighth.

13 Werner Laufer, “Lady Luck At Last Shines On Kiki Cuyler” (NEA), Freeport (Illinois) Journal-Standard, September 7, 1929, 10.

14 “Cubs Goats Become Heroes,” Chicago Tribune, October 12, 1929, 23.

15 John Drebinger, “Cubs Triumph, 3-1, In 3d Series Game Before 30,000 Fans, New York Times, October 12, 1929, 1.

16 The Sporting News, August 4, 1932, 4.

17 The Sporting News, March 31, 1932, 5.

18 Associated Press, “Hack Wilson Puts on Vaudeville Act,” Sarasota (Florida) Herald-Tribune, October 9, 1930, 1.

19 The Sporting News, July 24, 1930, 3.

20 The Sporting News, February 22, 1950, 20.

21 The Sporting News, March 24, 1932, 3.

22 The Sporting News, February 22, 1950, 20.

23 The Sporting News, July 11, 1935, 1.

24 Waldo, 212.

25 The Sporting News, February 22, 1950, 20.

Full Name

Hazen Shirley Cuyler

Born

August 30, 1898 at Harrisville, MI (USA)

Died

February 11, 1950 at Ann Arbor, MI (USA)

If you can help us improve this player’s biography, contact us.