Miami Amigos

This article was written by Eric Robinson

This article was published in The National Pastime: Baseball in the Sunshine State (Miami, 2016)

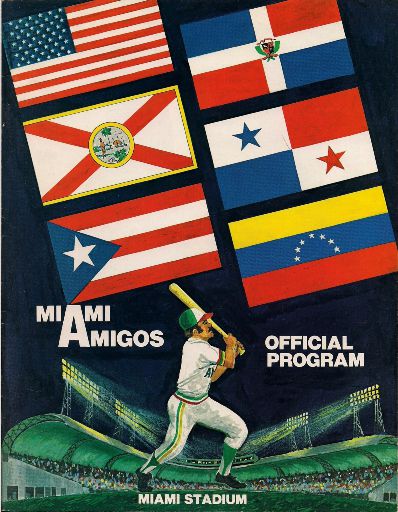

The cover illustration to the Amigos program shows the distinctively cantilevered roof of Miami Stadium, later known as Bobby Maduro Stadium.

Ever since the 1963 minor leagues realignment, the leagues that have held the Triple-A classification have been fairly consistent. The International League and Pacific Coast League have been fielding teams annually since then, with the American Association joining in 1969 before being disbanded in 1997 and having its teams absorbed by the other two leagues. Astute fans of baseball being played in other countries will be aware that the nonaffiliated Mexican League has held the Triple-A designation since 1967. What many may not realize is that for several months in the spring and summer of 1979 that there was one other Triple-A league, the Inter-American League (or IAL). The league was the dream of Roberto “Bobby” Maduro, a Cuban exile who was working as Coordinator of Inter-American Baseball for Commissioner Bowie Kuhn.1 This ambitious league had six teams in three different Latin American countries (the United States, Venezuela, and Panama) with its flagship franchise being the sole team based on the mainland United States, the Miami Amigos.

Maduro had been the owner of the Havana Sugar Kings of the International League since 1954. He had to relocate the team to Jersey City in 1960 due to Fidel Castro nationalizing control of American businesses in Cuba.2 At the end of the 1961 season Maduro moved the franchise to Jacksonville, Florida, where they became the Jacksonville Suns.1 In 1963 Maduro sold his 51% ownership stake of the Suns in a sale of stock to the people of Jacksonville but remained with the team acting as it’s General Manager.2 Maduro resigned from his position following the 1965 season but he stayed involved in professional baseball, taking a position in the major league office while working toward his goal of establishing professional baseball league in Latin America.

On December 31, 1978, Maduro resigned in order to prep for the inaugural season of the Inter-American League which was to begin four short months later on April 11, 1979.3 The Miami Amigos were organized prior to the teams located in the Dominican Republic, Panama, Puerto Rico, and Venezuela.4 The owners were established South Florida baseball men: Ronald Fine and Joe Ryan who owned the Class-A Miami Orioles of the Florida State League. The cost for the franchise was $50,000.

The duo announced to the public the creation of the team at an event in September of 1978 that also featured Miami mayor Maurice Ferre as a speaker. The mayor stated, “This is one of the most significant developments to happen in Miami in recent years,” which proved to an overly enthusiastic prediction of the importance of a baseball franchise that would be defunct before July of the following year.5

The team was to play its games at Miami Stadium, the home to Fine and Ryan’s other team, the Miami Orioles. The stadium was opened in 1949 in the Allapattah neighborhood and had been used as a Spring Training home for the Brooklyn/Los Angeles Dodgers and Baltimore Orioles, as well as various South Florida minor-league and college teams.6 When it opened, baseball commissioner Happy Chandler declared that he knew of “no more beautiful park anywhere.”7

Miami Stadium was no longer in its original splendor but was still a serviceable stadium for a Triple-A team. The stadium had a seating capacity of 9500, down from its original 13,000, when the Amigos began play in 1979. This made it the smallest of the stadiums in use by the teams in the IAL by nearly 5000 seats.8 Despite this smaller size, the team was second in attendance for the league behind the Caracas Metropolitanos in Venezuela.

The Amigos’ uniforms reflected the Latin American influence that was a significant part of both the city of Miami and the IAL. The team’s colors were green with red and yellow trim. While the home uniform was a basic white jersey with white pants, the road jersey was a garish bright green V-necked pullover with the team city and name written across the chest in bold yellow letters with red trim. The logo had Miami written above Amigos with the two words sharing a large A. The team’s cap was in a pinwheel style that was popular during the time with a red bill, a white front panel with a large red M joined with a pointed green A, and a green back.

The players wearing these uniforms were a motley bunch of ex-major leaguers, young Latin talent, and other assorted players and characters thrown in. The highest-profile person affiliated with the Amigos was future world champion manager Davey Johnson.

The scrappy three-time Gold-Glove-winning infielder had finished his 13-year major league playing career the previous season as a pinch hitter and third baseman for the Chicago Cubs. Johnson was 36 when Fine and Ryan hired him for his first managing job. Even though he was hired to manage the Amigos, he also got 25 at bats for the team playing in limited use. Johnson would later say that his time as Miami’s skipper was difficult but when asked to reflect on the experience he stated he learned important skills such as, “putting a team together from scratch, judging talent, putting a lineup together, putting a pitching rotation together…all of that helped.”9

Johnson described the roster as “probably the best Triple A club in existence.”10 Of the 30 different players who wore the Amigos green and red over the course of the team’s 72 games, 17 had at one time played in the major leagues and pitcher Porfi Altamirano would later debut with the Philadelphia Phillies in 1982.

The Amigos featured several players with circumstances that were unique to say the least. Oscar Zamora had pitched parts of four seasons in the big leagues with the Chicago Cubs and the Houston Astros. By 1979 he owned a successful shoe factory located in Miami and due to the obligations of that job, the 34-year-old could only travel to away games on the weekends.11 Despite these restrictions, Zamora was tied for second on the team in wins with eight.

Another player with restrictions on when he could play was outfielder and one-time Milwaukee Brewers top prospect Danny Thomas. Thomas earned the nickname the Sundown Kid due to his affiliation with the Worldwide Church of God and his adherence to their belief of not working between sundown on Friday and sundown on Saturday.12 His season was cut short following a suspension for an “unnecessary” argument with an umpire which also brought his pro career to an end just three seasons after he had been the Eastern League’s Triple Crown winner.13 The following year he committed suicide in an Alabama jail cell he was in due to allegations of sexual assault of a minor.14

The team’s top pitcher was Mike Wallace who earlier in the decade had a strong season with the New York Yankees. Wallace would lead both the team and league in wins with a dominant record of 11–1 while also posting a strong ERA of 2.27. The team also featured the Tyrone brothers, Jim and Wayne, who starred as the top hitters in the IAL.15 Jim, a one-time Cub and Athletic, lead the league with a .364 batting average. His younger brother Wayne hit a league-leading eight home runs that season. His most high-profile moment would come in 1983 when the Texan would appear on The Price is Right and win a new car.16

Difficulties faced by the Amigos during the season-opening road trips were indicative of the mixture of offbeat snags and serious problems the team and the league would face in its three-month existence. The season began on April 11, 1979, with a game in Panama City against the Panama Banqueros, followed by a series against the Caracas Metropolitanos. However, the team did not get to don their memorable bright green uniforms for these games, nor did they even get to play wearing uniforms with the actual team name on them. Pitching coach Oscar Pena explained, “We got these beautiful new uniforms and somebody stole them out of Miami Stadium so for the first few games we had to wear uniforms that said Miami Marlins.”17

The trip from Panama to Venezuela revealed the visa complications that would play a part in the downfall of the IAL. The league was playing in four different countries and had players from even more, and the teams would encounter hassles as they traveled from country to country. As the team arrived in Venezuela, the authorities refused to admit a player from Nicaragua and Cuban catcher Jorge Curbelo.18 In addition to Curbelo not being allowed to play the series, the Amigos faced another problem after their series with the Metropolitanos was complete, the team could not find the backstop. After finally reaching his mother on the telephone, Amigos officials found out that he was at his home taking a nap.19

Despite these early setbacks, the Amigos immediately proved to be the top team in the league. The talent that team officials assembled and Davey Johnson led went on to finish with a season (and franchise) record of 51–21 and include the IAL’s pitching and hitting leaders.20 The next best team had 14 fewer victories. The atmosphere at Miami Stadium for Amigos games was just as festive as the jerseys the team wore, with the crowd bringing conga drums and other percussion and beating out Latin rhythms throughout the game.21 In another departure from the staid world of major league baseball, the team had their own cheerleaders that went by the name of the “Hot and Juicy Wendy’s Girls.”22

Their winning ways and party-like vibe in the stands was not enough to bring folks out to the Amigos’ games. Despite strong early attendance and a showdown between one-time Cy Young winner Mike Cuellar with the hometown shoe industry businessman/part-time pitcher Oscar Zamora that attracted over 3,000 spectators, the average attendance for the games at Miami Stadium was only 1,350 people.23,24 Fine and Ryan even offered a promotion where fans could purchase a joint season ticket with Ryan’s Miami Orioles for all of the two teams’ combined 130 home games for $250. However, this did not draw out South Florida’s baseball obsessives. A major problem that the Amigos and other teams in the IAL faced were lack of both television and radio broadcasts, which cost them a major source of revenue, as well as the opportunity to draw fans to the ballpark. Only one IAL game was broadcast in Miami, and that was on the radio.25

And while operations in Miami were run like a Triple-A team, not all franchises were run to that professional level. In Panama, the Amigos had to play one afternoon game without a scoreboard as the operator was only hired to work night games.26 That game was called early due to rain despite the team having a modern tarp just for any potential rain delays. The problem was the grounds crew consisted of children that had not been instructed on the proper way to cover the infield. One game the Amigos played in Venezuela had to called early when the stadium’s lights went out and never came back on.27

Another significant problem not just for the team but for the entire league was the cost and scheduling of the air travel between the Caribbean countries. DC-10 planes were grounded following an American Airlines crash which made the already problematic logistics even more difficult.28 The Amigos had few flights in their entire existence that were less than an hour late.29 Other problems included the team having to take separate flights, with one of the flights arriving only minutes before game time, games starting at 10:00PM, and others being called early so the teams could reach the airport in time.

By June, the league lost two of its six franchises, San Juan and Panama. The league then divided the schedule into halves and awarded the first half pennant to Miami with their 43 wins in their first 60 games. The Amigos would only play 12 more games following this split. Following two other teams announcing they wanted to suspend operations for a year, Bobby Maduro announced on June 30 that he would be shut downing the IAL. He promised that it would return in 1980, but those plans never came to fruition.

The season began with the team not wearing their own uniforms and ended with the Amigos playing their final games without their manager guiding them. Johnson was still suffering from an injury that occurred from a home-plate collision during his time as a Phillie in 1977 and was in traction following the removal of two disks in his back.30 This experience managing the Amigos helped Johnson as in 1981 he took a position as the manager of the Mets Double-A team in Jackson, Mississippi, and by 1984 he was manager of the big league New York Mets. In 1986, he skippered that team to a World Series victory over the Boston Red Sox.

For a number of the Miami Amigos, this was their last stop playing professional baseball. Fine and Ryan continued to be involved in Florida baseball. Bobby Maduro never was able to start his dream of a Latin American professional baseball league and when he passed away in 1986 from brain cancer it was still too early to see the Florida Marlins expansion team. He did receive a lasting posthumous honor when in 1987 Miami Stadium, the one-time home of the Miami Amigos, was renamed Bobby Maduro Miami Stadium as a tribute to his being a friend to baseball in the Miami region.31

ERIC ROBINSON is an educator and writer in Denton, Texas. He has presented his research on Central Texas Negro League history and other topics to groups ranging from the SABR National Conference, regional SABR conferences, elementary schools, Nerd Nite, and on Central Texas NPR. He can be contacted at ericrobinson1776@gmail.com and his website can be visited at www.lyndonbaseballjohnson.com.

Notes

1. John Cronin, “When a Dream Plays Reality in Baseball: Roberto Maduro and the Inter-American League,” SABR Baseball Research Journal, Vol. 40, No. 1 (Spring 2011), 88–93.

2. “International League in Cuba:50 Years Later,” The International League Historical Scrapbook (2010), 8-9. http://www.milb.com/documents/2010/08/06/13100514/1/Cuba.pdf Date Accessed February 25, 2016.

3. Cronin, 88–93.

4. Bill Colson, “The Over the Hill League,” Sports Illustrated, June 4, 1979.

5. “Triple A Team Set for Miami,” St. Petersburg Times, September 15, 1978.

6. Robert Andrew Powell, “Rough Diamond,” Miami New Times, August 15, 1996. http://www.miaminewtimes.com/news/rough-diamond-6361494. Date Accessed February 25, 2016.

7. Powell, “Rough Diamond.”

8. Cronin, 88–93.

9. Gary Long, “For Johnson, Mets a Snap After Amigos,” Miami Herald, March 28, 1987.

10. Colson, “The Over the Hill League.”

11. Long, “For Johnson, Mets a Snap After Amigos.”

12. Long, “For Johnson, Mets a Snap After Amigos.”

13. Bruce Markusen, “The Short, Wild Life of the Inter-American League,” The Hardball Times, July 8, 2014. http://www.hardballtimes.com/the-short-wild-life-of-the-inter-american-league/. Date accessed February 25, 2016.

14. Markusen, “The Short, Wild Life of the Inter-American League.”

15. Cronin, 88–93.

16. Cronin, 88–93.

17. Sam Jacobs, “A Vanishing League,” Miami Herald, July 4, 2004.

18. Long, “For Johnson, Mets a Snap After Amigos.”

19. Long, “For Johnson, Mets a Snap After Amigos.”

20. Baseball Reference, http://www.baseball-reference.com/register/ league.cgi?id=b950ed7f. Date accessed February 25, 2016.

21. Colson, “The Over the Hill League.”

22. Markusen, “The Short, Wild Life of the Inter-American League.”

23. Colson, “The Over the Hill League.”

24. Cronin, 88–93.

25. Jacobs, “A Vanishing League.”

26. Jacobs, “A Vanishing League.”

27. Jacobs, “A Vanishing League.”

28. Markusen, “The Short, Wild Life of the Inter-American League.”

29. Colson, “The Over the Hill League.”

30. Long, “For Johnson, Mets a Snap After Amigos.”

31. Cronin, 88–93.