When a Dream Plays Reality in Baseball: Roberto Maduro and the Inter-American League

This article was written by John Cronin

This article was published in Spring 2011 Baseball Research Journal

Independent minor leagues returned to the baseball landscape in the 1990s and have continued to sprout during the first decade of this century. Some leagues lasted just one season while others have been more successful. This is a return to older times. During the earliest parts of the twentieth century, minor leagues were part of Organized Baseball but operated in an independent manner; they were not owned by (or even had working agreements with) major league teams. Therefore, these teams had to fend for themselves, financially, operationally, and, in particular, in securing and maintaining a competitive roster for each season.

All this had changed long before the 1970s. All minor-league teams by that time had an affiliation with the major-league teams. The one exception during that era was the Inter-American League, a true “indie” which began play in the 1979 season. The realities, however, of independent baseball—the need for purposeful marketing and business development, a developed fan base and low overhead costs—put the Inter-American League in jeopardy from the outset. The league was the dream of Roberto Maduro, a wealthy man born on June 27, 1916, in Cuba. He had been the owner of the Havana Sugar Canes, a team that played in the Triple-A International League in the 1950s. After Fidel Castro came to power, Maduro fled Cuba with his riches left behind, lived in exile, and began his life all over again. The franchise shifted to Jersey City in 1960. Commissioner William D. Eckert named Roberto Maduro Coordinator of Inter-American Baseball in 1966.

All this had changed long before the 1970s. All minor-league teams by that time had an affiliation with the major-league teams. The one exception during that era was the Inter-American League, a true “indie” which began play in the 1979 season. The realities, however, of independent baseball—the need for purposeful marketing and business development, a developed fan base and low overhead costs—put the Inter-American League in jeopardy from the outset. The league was the dream of Roberto Maduro, a wealthy man born on June 27, 1916, in Cuba. He had been the owner of the Havana Sugar Canes, a team that played in the Triple-A International League in the 1950s. After Fidel Castro came to power, Maduro fled Cuba with his riches left behind, lived in exile, and began his life all over again. The franchise shifted to Jersey City in 1960. Commissioner William D. Eckert named Roberto Maduro Coordinator of Inter-American Baseball in 1966.

In this position, Maduro boldly asked the United States State Department to purchase baseball equipment that would be given to Latin American countries. Maduro stated that such a donation would generate good will for the United States in those countries. Notwithstanding the fact that by 1963, Cuba was now ruled by Castro, an ardent baseball fan, Maduro had stated, “Wherever baseball is played, people love the Americans.”[fn]The Sporting News, 23 February 1963, 21.[/fn]

Was this an overly sunny view? Many instances prior to 1966 show Roberto Maduro to be an eternal optimist who viewed the baseball world in Latin America with rose-colored glasses.

Related link: Interesting Inter-American League Items, by John Cronin

At the start of the 1955 season, Maduro stated that every effort would be made to raise the Sugar Canes’ attendance to 500,000 from the previous season’s total of 295,453. When the season was concluded, however, “only” 313,232 fans had attended Sugar Canes games.[fn]The Sporting News, 20 April 1955, 35.[/fn]

Two months after opening day, he toned down his prediction by pointing out that during the 1954 season, the team had drawn 200,000 fans during the first half of the season but only 95,000 during the second half.[fn]The Sporting News, 22 June 1955, 24.[/fn]

During that same 1955 season, Maduro stated, “I believe our chances of securing a major-league franchise in the next few years are good.”[fn]The Sporting News, 4 May 1955, 30.[/fn]

Toward the close of 1957 season, Maduro reaffirmed his intention of operating his Havana team in 1958. He said he believed that the Cuban political situation would be resolved by the start of the season.[fn]The Sporting News, 18 September 1957, 44.[/fn] Baseball people in the United States, however, felt that the political unrest in Cuba made the Sugar Canes’ future uncertain. A hopeful Maduro stated that the Castro uprising was no factor at all.[fn]The Sporting News, 11 December 1957, 34.[/fn]

During the offseason between the 1958 and 1959 seasons, Maduro was quoted predicting that “I think there will be less political unrest”[fn]The Sporting News, 26 November 1958, 35.[/fn] when questioned about Cuba’s political situation.

In January 1959, The Sporting News reported that in Maduro’s opinion, the culmination of the political upheaval in Cuba—with Castro successfully overthrowing

dictator Fulgencio Batista—would have a beneficial effect on International League baseball. Maduro boldly stated, “For the first time in the five-year life of the club, it now appears we will be able to operate in an atmosphere of peace and security.”[fn]The Sporting News, 14 January 1959, 19.[/fn]

Several weeks later, Maduro was again reported to believe that Castro’s regime would benefit baseball on the island.[fn]The Sporting News, 4 February 1959, 26.[/fn] [fn]The Sporting News, 11 February 1959, 23[/fn]

Within the next year and a half, however, Maduro and his family had to flee Cuba for fear of their lives and the Havana Sugar Canes were uprooted and replanted in Jersey City.

Maduro’s grasp of reality concerning baseball in Latin America may well have been severely blinded by his dreams. This frame of mind and reference are paramount to keep in mind as Maduro took further positions in baseball.

Maduro continued as Coordinator of Inter-American Baseball under the direction of Eckert’s successor, Bowie Kuhn.

Maduro resigned his position with the commissioner’s office on December 26, 1978, effective year-end. He left because he felt that it was an opportune time to make his dream a reality. During the late 1970s, the minor leagues were beginning to show signs of a revival. Columbus, Ohio had been without a professional baseball team for six years after a long history of fielding teams which competed in the Triple-A American Association and the International League. The local government spent over $5 million to refurbish its existing stadium. As a result, Columbus was able to secure a franchise in the IL for 1977. While the team finished in seventh place, they won the attendance prize that year in the minor leagues by drawing 457,251 fans.

Such success stories may have pushed Maduro to pursue his dream even more fervently. He assumed that the rivalry between the countries in Latin America would stir up fan interest.

His decision to form a new league did create a rivalry in Latin America, but one that Maduro neither anticipated nor wanted. The Inter-American League (IAL) was immediately decried by operators of clubs in the winter leagues in Venezuela, the Dominican Republic, and Puerto Rico. In fact, following Bowie Kuhn’s approval for the establishment of the IAL, officials of the Puerto Rican Winter League vowed to vote at the end of the 1979 baseball season to end the contract between the Caribbean Baseball Confederation and the major leagues.[fn]The Sporting News, 3 February 1979, 46.[/fn]

Even with these threats, the IAL began play as a six-team Triple-A league on April 11, 1979. The Miami Amigos represented the United States, the Caracas Metropolitanos and the Maracaibo Petroleros de Zulia played for Venezula, Panama boasted the Banqueros, the Puerto Rico Boricuas played in San Juan, and the Santo Domingo Azucareros took the field in the Dominican Republic.

The league was widely dispersed geographically, making travel expenses considerably higher than those in other Triple-A leagues. Distance between IAL cities made air travel for all teams a necessity. The problem of already prohibitively high air fares was further compounded by the grounding of the DC-10 airplane.[fn]The Sporting News, 4 August 1979, 47.[/fn]

And the teams in the other Triple-A leagues (the International, Pacific Coast, and Mexican Leagues and the American Association) had one important difference: the financial support of major league teams.

Another travel-related problem was visa problems on players entering and leaving the league’s various localities. Since Cuba and Nicaragua did not have good diplomatic relations with Venezuela, travelers were required to obtain permission from the Venezuelan government in order to enter the country. Because several players in the league hailed from these countries, teams often entered Venezuela shorthanded.[fn]The Sporting News, 9 June 1979, 42.[/fn]

By Maduro’s directive, each team posted $50,000 to defray costs relating to the commissioner’s office and umpires. Maduro, in retrospect, was overly optimistic when questioned if the league had the capability to finish its first season with a 130-game, five-month schedule. His response was, “We are not worried about finishing the season. We have enough money to operate three or four years.”[fn]The Sporting News, 5 May 1979, 41.[/fn] But on June 30, 1979, the league suspended operations for the season and never played another game.

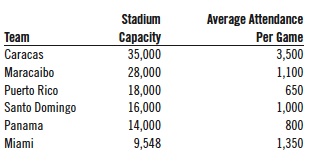

It appears that Maduro’s desire to promote Latin American summer professional baseball clouded his sense of sound business practice. He felt that the league’s stadium capacities, which ranged from Miami (the smallest, at 9,500) to Caracas (the largest, at 35,000), would ensure success. The stadium sizes and the average attendance per game for each team are listed below:

That the IAL’s games were played in nearly empty stadiums tells the story of the league’s financial position. Stadium size does not insure automatic success, contrary to the Field of Dreams catchphrase (“If you build it, they will come”). To be successful, a product must be good and must be marketed properly. Radio and television contracts were to be an important source of revenues for the teams and the league, but only Caracas, Maracaibo, and Santo Domingo had full-season radio broadcasts. Caracas had the league’s only television package and that for just a few early-season contests. Miami broadcast only one game on the radio and Panama had no media exposure whatsoever.[fn]The Sporting News, 21 July 1979, 52.[/fn]

After the league suspended operations, Maduro conceded that the league didn’t begin marketing until late January 1979; at which point it “was too late to interest TV or big advertisers.” In his rush to move forward with his decade-long dream, he instead created a financial nightmare.

He had held this dream for over ten years. Back in 1968 on a trip to Mexico, Maduro stated that he was working on plans to establish other summer leagues besides the Mexican League in Latin American.[fn]The Sporting News, 4 May 1968, 36.[/fn] This is what is difficult to understand: Why, after waiting all those years, did Maduro feel that he had to rush his dream, the Inter-American League, onto the playing field in 1979 without proper marketing or cost analysis?

In retrospect, league officials should not have rushed their product. Instead of actually playing baseball, they should have spent 1979 planning baseball. Bernardo Benes, part owner of the Panama Banqueros, concurred and said, “The idea was good, but the planning should have taken another year.”[fn]The Miami Herald, 3 July 2004, “Inter-American League Folded in Less Than a Year.”[/fn] Maduro should have required written business plans from each potential team owner. Such plans should have included a feasibility study, a financial plan with several contingency scenarios analyzed, facility viability, a marketing plan, demographic studies, and an analysis of all potential revenue sources.

It is quite possible that had these studies been conducted, the league might have never gotten off the ground. There is no proof that any high-placed officials did due diligence prior to Commissioner Bowie Kuhn giving his approval to the new league. In his autobiography, Hardball: The Education of a Baseball Commissioner, Kuhn makes it obvious he was a big fan of the minor leagues. He wrote the following:

One of the joys of travel for me was the minor-league ballparks and people. I always felt that the heart of baseball was in those nostalgia-laden bandboxes and hard-striving people. There was a rich-textured, profound feel of the game in the minors that I found nowhere else, something closer to the game I first knew as a lad in Griffith Stadium and Forbes Field. So I beat my way across the minors from the Carolinas to Oregon, from Connecticut to West Texas, and I ate their hot dogs, savored their hospitality, and told them how much I cherished them.[fn]Bowie Kuhn, Hardball—The Education of a Baseball Commissioner (New York, NY: Times Books, 1987), 44.[/fn]

Kuhn, however, makes no mention of either the Inter-American League or Roberto Maduro in his 440-page book. It is possible that Kuhn didn’t want to dwell on a negative of his administration. Had Commissioner Kuhn and/or his advisors done their homework, they might have offered some well-placed constructive criticism to urge IAL officials to delay the league’s inaugural season to 1980.

With better planning, the IAL might have been ruled an economically unfeasible enterprise. Proper business practices might have burst Maduro’s bubble before it had been blown. It is possible that Kuhn was thinking like a fan rather than the Commissioner of Baseball when he gave his approval for the IAL, and there may have been some sentiment toward letting Maduro have his own way.

Some baseball officials saw the foolishness in the league. The Sporting News ran the following quote from an unidentified major-league official shortly after the IAL’s demise:

It’s another example, in my opinion, of the head people in baseball not listening to knowledgeable baseball men. It was a big political deal. They were afraid of two guys who got it started in Washington. They announced the formation of the league in Washington at the headquarters of the Organization of American States. We all knew in our hearts this thing wouldn’t work. It couldn’t work. They were flying 15, 18, 20 people across the seas. You know what air fares are today. It was absurd.[fn]The Sporting News, 18 August 1979, 47.[/fn]

Further research has disclosed that this unidentified official was Dallas Green,[fn]Frank Dolson, Beating the Bushes (South Bend, Indiana: Icarus Press, 1982), 227.[/fn] who at the time was the manager of the Philadelphia Phillies. This after-the-fact prediction of failure might have been the result of Green’s feelings toward Kuhn. Green, later a GM for the Cubs and manager of the Yankees and Mets, apparently resented lawyers (Kuhn was a lawyer) and also resented directions from the Commissioner. Kuhn felt that Green had “chafed” over his decisions in a number of cases.[fn]Bowie Kuhn, Hardball—The Education of a Baseball Commissioner (New York, NY: Times Books, 1987), 372.[/fn]

Further research has disclosed that this unidentified official was Dallas Green,[fn]Frank Dolson, Beating the Bushes (South Bend, Indiana: Icarus Press, 1982), 227.[/fn] who at the time was the manager of the Philadelphia Phillies. This after-the-fact prediction of failure might have been the result of Green’s feelings toward Kuhn. Green, later a GM for the Cubs and manager of the Yankees and Mets, apparently resented lawyers (Kuhn was a lawyer) and also resented directions from the Commissioner. Kuhn felt that Green had “chafed” over his decisions in a number of cases.[fn]Bowie Kuhn, Hardball—The Education of a Baseball Commissioner (New York, NY: Times Books, 1987), 372.[/fn]

Was the league a success in any way? To decide, it may help to examine the league’s players. In an article “Summer Baseball Returns to Latin America” that appeared in TSN on May 5, 1979, Michael Janosky wrote:

Because it has no major-league affiliation, the IAL is not a Triple-A league in the classic sense. It’s more a clearing house for career minor leaguers, players who have run out of organizations offering them chances, former big leaguers making a last gasp attempt to get back and kids who have never played pro ball.[fn]The Sporting News, 5 May 1979, 41.[/fn]

Using Janosky’s above statement, we can separate the IAL players into three categories for further analysis. These categories will be simply called “Last Chance/Career Minor Leaguers,” “Former Major Leaguers,” and those who “Never Played Pro Ball Before the IAL.” All players will be classified in one of those three categories for analysis purposes. It is possible to argue that some of the players could be classified in multiple categories, but to simplify the process, players will be placed in only one category.

Several things can blur these categories. If a player spends most of his career in the minors but had one or more “cups of coffee” in the Show, how should he be classified? For this article, I place him with the career minor-leaguers. Also, if a player eventually appears in the majors after his participation in the IAL, he will also be classified as a career minor leaguer. A player who appears in the majors for an extended period of time after playing in the IAL will also be classified as a career minor leaguer. My reason for this is quite simple; in 1979, he was a minor leaguer.

One hundred seventy-three (173) men appeared in the short-lived IAL season. Of these, 102 were position players and 71 were pitchers. A majority of the IAL players—62.43%—are classified as Last Chance/Career Minor Leaguers.

The next category, Former Major Leaguer, accounted for 23.12% of the players in the league. These two categories totaled 85.55% of the IAL’s participants. This would support the IAL classification as a Triple-A league, the highest rung in the minor league ladder. Rosters of teams in this classification usually are stocked with veteran minor leaguers and former major leaguers. The one anomaly in the chart is that this league had 25 true professional rookies—men who never played professional baseball prior to their appearance in the IAL. Obviously, few in baseball begin their careers at the Triple-A level. Why 14% of the leagues’ players were rookies can be explained by the its (very) international nature and its independence from major league affiliations.

In order to fully evaluate the overall success or failure of this league, it would help to receive some input from actual players in the league. Therefore, I sent a questionnaire to a sample of IAL players. Their answers provide valuable insight into the league’s short history.

Former players were asked questions such as, Did you enjoy playing in the IAL? Do you feel that playing in the IAL helped, hurt,or had no effect on your career? And why? What was your favorite thing about playing in the IAL? What was your least favorite thing about playing in the IAL? Please describe the quality of play in the IAL. Why do you think that the IAL failed? All but one of the responding players enjoyed playing in the league. The player with the negative response was injured while playing in the league, making his response understandable. Another interesting response was from a former major leaguer who felt that telling the story of the IAL was a big money-maker and he wanted to be compensated for answering my questionnaire. (Maduro apparently wasn’t the only dreamer connected with the league!)

The reason players enjoyed the IAL could be attributed to the fact that they realized they were in the twilight of their careers and weren’t wearing rose-colored glasses. They absolutely knew “the score” of their individual careers at that point. An overwhelming majority of the respondents indicated that playing in the league had no effect on their baseball career. The responses from players indicate that these guys had no grand illusion that the IAL was a career-saver or a rebirth. One player indicated “No Effect— Over the Hill.” Another said, “No Effect. I was going to retire as a player and go into coaching after the season, anyway.”

Regarding their favorite thing about playing in the IAL, their answers were a little more diverse. Positive factors included travel, great cities, good food, and great fans. The most interesting response was, “The Comrade [sic]—Playing baseball with some of organized baseball’s renegades.” These men knew that they were unique players in a unique league that ended too soon for them.

Some of the former players’ least favorite things about the IAL give clues as to why the league fell apart. The players cited travel, customs, first-time problems, low pay, and the disorganized franchises in the Latin American countries. Obviously, most of these things were caused by and/or caused financial burdens that the teams couldn’t bear.

The IAL was classified as Triple-A, but interestingly, a majority of the veteran minor leaguers and former major leaguers polled pegged the level of play as Double-A. (Could false advertising be another reason for the league’s quick demise? Fans paid for and naturally expected a certain product that they did not necessarily receive. Disappointment with the level of play may have led to poor attendance.)

In all, it is difficult to attribute the failure of the IAL to one cause. A more accurate statement might be that several factors worked together to cause its downfall.

First and foremost, Roberto Maduro must shoulder the blame. He felt that his dream could become a reality in 1979 and was anxious to get the IAL off the drawing board and onto the baseball fields of Latin America. As discussed earlier in this article, Maduro admitted that the league didn’t start marketing itself until January 1979. What success could the league have experienced if instead of playing baseball during that season, Maduro and other league leaders as well as individual team executives had spend that season putting the league on a sound financial footing?

The best team in the league drew 3,500 fans per game, with the next highest average gate only 1,350. Why were the IAL’s games so poorly attended? The poor marketing of the league played a big part, but other factors contributed. There didn’t appear to be any real rivalries between the teams, at least the kind that generate fan interest. Had play been delayed for a year, fan interest could have been cultivated as part of the league’s preparation work.

Another key factor was high costs. Every trip had to be made by air, a very expensive mode of travel back in 1979, and it doesn’t take an accountant to see the disaster of low revenues and high expenses.

When Maduro passed away on October 16, 1986 at the age of 70 from brain cancer, it was front page news of El Nuevo Herald, the Spanish newspaper of Miami, Florida. Fausto Miranda, the dean of Cuban sportswriters, eulogized Maduro:

To remember the personality of Bobby Maduro as a distinguished Cuban sportsman does not do him justice. The death of Maduro is a loss for Latin America. The dreamer and enthusiast dedicated more than half a century of his 70 years to the enlargement of baseball ‘without borders and without prejudices,’ as he said himself. Maduro traveled all the paths of the great national sport.[fn]El Nuevo Herald, 17 October 1986, 1.[/fn]

In fitting tribute to Maduro, Miami Stadium was renamed Bobby Maduro Stadium in 1987. This stadium was home to the Miami Amigos. It also hosted spring training games for the Orioles and Dodgers as well as those of another doomed indie, the Senior League. The park stood as tribute to the man until it was demolished in 2001 to make way for an affordable rental housing complex.

Roberto Maduro’s dream of bringing summer professional baseball to Latin America met reality in 1979, and reality won. In the thirty years since, no summer pro baseball teams have played in Latin America. Maduro’s dream has remained just that: a dream.

JOHN CRONIN, a longtime SABR member, currently serves on the Minor League Committee. He is a lifelong Yankees fan whose special interest is Yankees minor league farm teams over the years. A CPA and retired bank executive, Cronin has a B.A. in History from Wag- ner College and an M.B.A. in Accounting from St. John’s University.