‘Momen’ and Monte: The Linkage Between Roberto Clemente and Monte Irvin

This article was written by Doron Goldman

This article was published in ¡Arriba! The Heroic Life of Roberto Clemente (2022)

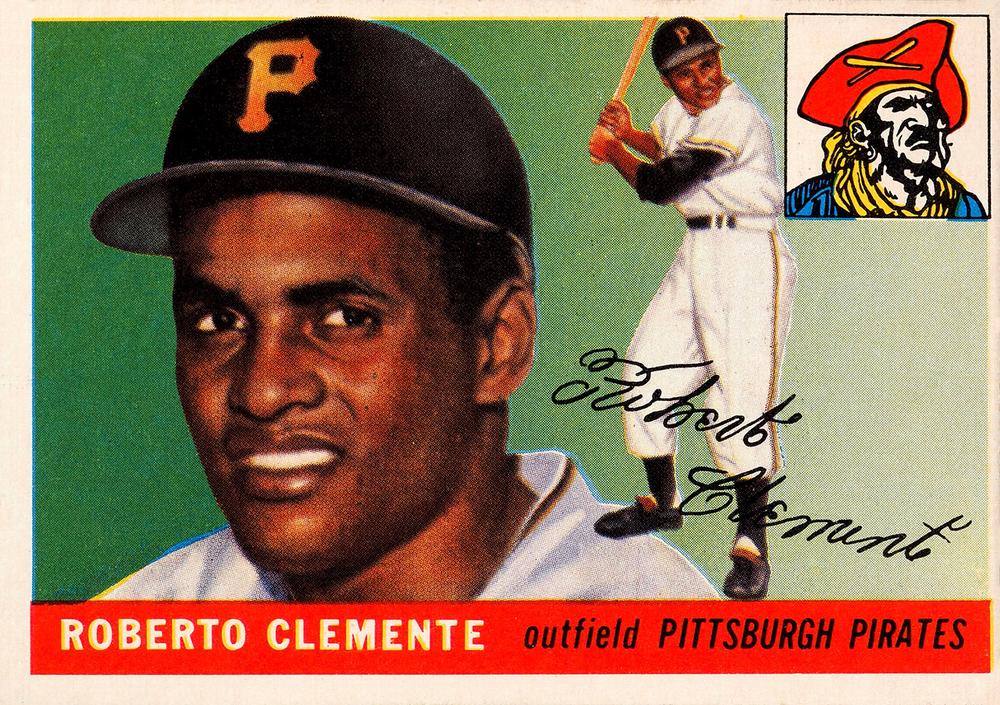

Roberto Clemente Walker was one of six baseball immortals inducted into Cooperstown’s Hall of Fame on August 6, 1973. Along with Clemente, pitching greats Mickey Welch and Warren Spahn, both 300-game winners, longtime AL umpire Billy Evans, New York Giants first baseman George “Highpockets “Kelly, and New York Giants and Newark Eagles star outfielder Monford “Monte” Irvin” were all celebrated that day.

“The Great One” had 167 at-bats vs. Spahn, as their careers overlapped 11 seasons, from 1955 (Clemente’s rookie season) through 1965. Clemente hit.407/.420/.605 for a 1.025 OPS (on-base plus slugging) against Spahn, with four home runs and only five walks and seven strikeouts – quite a success story.1 In addition, both Spahn and Clemente wore uniform number 21.

In contrast, Monte Irvin and Roberto Clemente played against each other only in 1955 and 1956. The connection between Irvin and Clemente, though, went back 10 years further than the confrontations with Spahn – to 1945, when Roberto was an 11-year-old baseball fanatic and Monte was playing winter-league baseball for the San Juan Senadores. Both “Momen” and Monte were outstanding players who significantly impacted others – and Monte had an important formative influence on Roberto. In addition, there were several interesting parallels in the lives and careers of Monte Irvin and Roberto Clemente – two pioneers of major-league baseball’s integration era.

MOMEN’S CHILDHOOD BASEBALL IDOL

As a child, Roberto Clemente was nicknamed Momen. When interviewed in the early 1970s, Roberto’s older brother, Matino, initially said that “[W]e called him Momen from the time he was little. When he had grown up and become a star, no one could remember what the name meant.”2 Thirty years later, according to author David Maraniss, Matino maintained that “Momen” was short for momentito, in English “wait a minute,” because Roberto would constantly say “momentito” whenever he was interrupted or was asked to do something.3 Either way, “to his family and Puerto Rican friends, at school and on the ball fields, Momen was his nickname from then on.”4

Roberto’s father, Melchor, was a foreman for a sugar-processing company, which meant that the family was not as poor as many other families in Roberto’s hometown of Carolina. But money was still not plentiful. Late in his tragically short life, Roberto described buying a secondhand bicycle for $27 with his own money – money made by waking up at 6 A.M. to deliver milk, earning a penny a day, for three years. As Roberto described it, he “grew up with people who really had to struggle to live”– and his father had said, “I want you to learn how to work and I want you to be a serious person.”5

By age 11, Roberto Clemente traveled from Carolina, where he lived, to San Juan to see his favorite baseball team, the San Juan Senadores, play at Estadio Sixto Escobar. He may well have used his recently purchased bicycle, but he sometimes traveled by bus, with his dad giving him 25 cents –10 cents for the bus and 15 cents for admission to the ballpark.6 Roberto was still looking for ways to avoid spending his dad’s hard-earned money, so some days, rather than paying admission, he apparently watched the Senadores from a tree overlooking right field.7

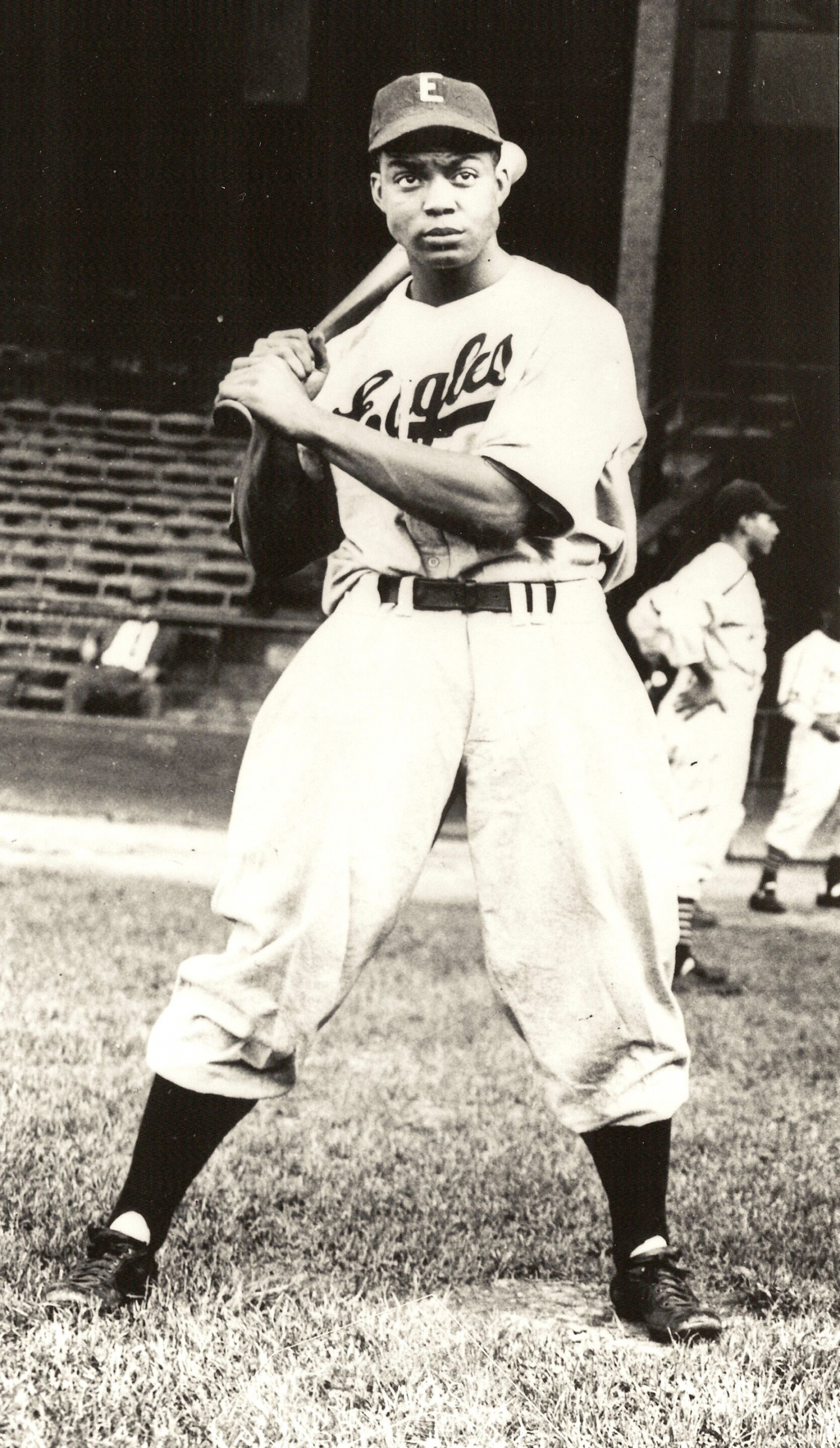

Wherever he was perched, Roberto’s eyes were riveted to one particular ballplayer – versatile outfield star Monte Irvin of the Negro National League’s Newark Eagles – and in the 1945-46 Puerto Rican Winter League season, primarily the second baseman for the Senadores.8 Irvin started his Negro League career by playing third base and then became the center fielder for the Eagles,9 but when he returned in 1945 to Puerto Rico, where he had previously played during the winters of 1940-41 and 1941-42, he discovered a set outfield of Felle Delgado, Luis Olmo, and Freddie Thon (Dickie Thon’s grandfather). According to Irvin, “(W)e needed a second baseman, and Olmo told me, ‘(Y)ou’re fast, can hit, and have a great arm, so why not?”10

Whether at second base or in the outfield, where Irvin did play a limited amount in 1945-46,11 he displayed that great arm – and Roberto was watching. In his autobiography, Irvin recalled, “[W]hen I went to Puerto Rico and played winter ball, the crowd would just oooh and aah when I warmed up” (italics in original). Not only was Roberto watching, but when he was unable to be in attendance, Momen listened at night to radio broadcasts of the San Juan games while he threw a rubber ball against the wall. “Irvin was my first idol because he was not only a good hitter, but he had such a good arm,” Clemente said.12

Monte Irvin was indeed a good, and perhaps a great, hitter. According to statistics reported by baseball-reference.com, Irvin led the Negro National League in batting with a .395 average in 1942 and a .369 mark in 1946.13 He said that he came back from World War II service overseas “with three years of athletic rust and a bad case of war nerves, and I needed to work back into my pre-war playing condition. … So, I said, ‘I’ll start to climb back slowly.… And, in order to regain my old form, I went down to San Juan, Puerto Rico, and played ball that winter.”14

All he did was hit .368 for San Juan, barely losing the batting title to Ponce’s Fernando Diaz Pedroso.15 Yet Irvin won the Puerto Rico Winter League MVP award, and in the league championship series against Mayaguez, he smashed three home runs in a doubleheader sweep by the Senadores as they took the series, four games to two.16 It is unknown whether Roberto attended these games, but it seems likely that in 1962, such performances led Clemente to praise Irvin to the New Pittsburgh Courier’s Bill Nunn Jr., saying, “I think he had the best eye, best stance, and sharpest cut of any of the big leaguers who play winter ball in Puerto Rico. He also (fielded) real good and (threw) like a bullet.”17

Throwing like a bullet is a description that clearly applied not only to Monte Irvin. After all, Roberto Clemente had 10 outfield assists in his first 55 major-league games for the 1955 Pittsburgh Pirates, and The Sporting News contributor and Pittsburgh Press sportswriter Les Biederman commented that “the Pittsburgh fans have fallen in love with his spectacular fielding and his deadly right arm.”18

While Clemente led the National League in outfield assists five times during his 18-year major-league career,19 Irvin ranked in the top five in assists by a left fielder four times, the only four times he played more than half the league’s games in the outfield.20 And while Michael Humphreys’ book Wizardry rates Roberto Clemente as the best defensive right fielder of all time by a substantial margin, it rates Monte Irvin as the 10th best defensive left fielder of all time despite his short, eight-season career in the formerly White major leagues and states that “Irvin may have been the best fielding left fielder before the Modern Era (1969-1992).”21

One element of youth competition that the two ballplayers had in common was that they each participated in track and field. In Irvin’s case, he “threw the javelin, the shotput, and the discus” and set the state record for throwing the javelin with a heave of 192 feet 8 inches.22

In Clemente’s case, he threw the javelin 195 feet, but also jumped 6 feet in the high jump and 45 feet in the triple jump.23 According to Clemente biographer Bruce Markusen, “Clemente’s expertise in the javelin aided him in playing baseball. He may not have known it at the time, but the footwork, release and general dynamics employed in throwing the javelin coincided with the skills needed to throw the baseball properly.24

According to David Maraniss, “[T]he javelin became an iconic symbol in the mythology of Clemente. It represented his heroic nature, since the javelin is associated with Olympian feats.”25

It has been said by many that Monte Irvin was Roberto Clemente’s boyhood hero. In the words of Clemente:

I used to watch Monte Irvin play. When I was a kid, I idolize him. I would never have enough nerve. I did not want to look at him straight in the face. That why when he pass I turn around and look at him.26

Monte Irvin elaborated further:

I first met Roberto Clemente in the early 1940s in Puerto Rico. I used to play down there. This is when I was in the old Negro Leagues. He was just a youngster. And one day I let him carry my bag in order to get into the stadium. So we became friendly. Used to give him a ball.… I don’t know … might have given him a glove that I had but I never did see him play.27

It is not entirely clear how the relationship developed. In an interview Irvin gave to SABR member Stew Thornley in 2005, he made it clear that Clemente was one of many kids who wanted to get into the ballpark, but that he did not get to know a young Roberto at the time: “They wanted to get into the game, and I let them take my bag in, so they wouldn’t have to pay. You know, kids hanging out outside the game, and we’d give them our bags so they could take them in and get in free.”28

In contrast, Maraniss indicated that Irvin and Clemente developed a friendship when Clemente was a teen: “Just by being there, hanging around, as shy as he was, Clemente eventually struck up a friendship with Irvin. And Irvin made sure that his young fan got in to watch the game, even without a ticket.”29 And in his autobiography, Irvin stated, “[W]hen Clemente was a youngster … he was a protégé of mine.”30

There is no doubt, however, that upon becoming a major-league player, Clemente told Irvin about the impact Irvin made upon him as a teenager. The young professional let Irvin know that he admired his throwing arm and had modeled his throwing motion after it: “He told me he admired, not only the way I hit the ball, but also the way I threw the ball. He wanted to throw the way that I did and later, when he had one of the best throwing arms in baseball, I considered it a compliment.”31 Irvin clearly was proud of the “mentoring relationship” that he had with young Clemente, as he told Maraniss: “(Y)eah, I taught Roberto how to throw.… [O]f course, he quickly surpassed me.”32

THE DODGERS AND THE GIANTS — AND THE PIRATES AND THE CUBS

Both Clemente and Irvin had some history with each of the two New York National League teams. Irvin signed with the Brooklyn Dodgers’ St. Paul farm team after the 1948 season, when the Negro National League folded. Newark Eagles owner Effa Manley objected to the signing because Dodgers general manager Branch Rickey refused to compensate her for Irvin’s contract, so Rickey released Irvin.33 Subsequently, Irvin was signed in 1949 by Horace Stoneham, the New York Giants owner, who paid $5,000 to the Eagles owners, past and present, for Irvin’s contract.34

Clemente was also first signed by the Dodgers, who first spied Roberto at a tryout at Sixto Escobar Stadium on November 6, 1952. Dodgers scout Al Campanis characterized Clemente as follows: “Has All the Tools and Likes to Play. A Real Good Looking Prospect!”35 It was the Giants, though, that first made an offer to Clemente after Pedrin Zorilla, the Santurce Cangrejeros owner,36 for whom Roberto played in the Puerto Rico Winter League, touted Clemente to Stoneham. The Giants, however, refused to spend $4,000 on Clemente, so Zorilla, who had an informal relationship with the Dodgers, turned to Campanis.37 The Dodgers’ top farm team, the Montreal Royals, offered Clemente a $5,000 contract with a $10,000 signing bonus, and he signed on February 19, 1954.38

Roberto Clemente played sporadically for the Royals, in 1954, batting only 148 times with a .257/.286/.357 slash line for a .657 OPS – hardly the performance of a future superstar.39 It has been endlessly debated whether the Dodgers were nonetheless trying to hide Clemente by playing him infrequently. It is undisputed that Clyde Sukeforth, a former Dodgers scout and the first major-league manager (for one game) of Jackie Robinson, wanted Clemente for the Pittsburgh Pirates. Said Sukeforth: “I saw Clemente throwing from the outfield and I couldn’t take my eyes off him.”40

The Dodgers knew when they signed Clemente that they could potentially lose him to the minor-league draft after the 1954 season, because they paid him a bonus of more than $4,000, and a rule passed by the major-league owners in December of 1952 stated that any player who was given a bonus of that size by a minor-league club had to go through an unrestricted draft before he could be assigned to the parent major-league club.41 The Dodgers, according to E.J. “Buzzie” Bavasi, signed Clemente just to make sure that the Giants did not get him: “[W]e didn’t want the Giants to have Clemente and a fellow like Willie Mays in the same outfield.”42 In 1956, former Giants (and before that, Dodgers) manager Leo Durocher told Les Biederman that “[W]e knew the boy [Clemente] in high school.… [W]hen the Dodgers heard we were after him, they got into the act.”43

Perhaps the Dodgers also were aware that Clemente could complete an outstanding outfield featuring him in right field, Willie Mays in center, and Monte Irvin in left – three future Hall of Famers, all with outstanding throwing arms, not to mention other baseball talents. Though Irvin’s career was about to take a downturn when Clemente signed in early 1954, he was coming off a stellar season, batting .329 with 21 home runs and 97 runs batted in only 444 at-bats.44

At the end of the 1954 season, the Pirates, who had finished last again in the National League, picked first in the minor-league draft and chose Clemente. In 1955, when Clemente was a rookie, Irvin was sent to the minor-league Minneapolis Millers in late June.45 Irvin starred for the Millers, hitting .352 with 14 home runs and 52 RBIs and figured prominently in their Junior World Series victory. As a result, like Clemente a season earlier, Irvin was drafted by the Chicago Cubs in the season-end minor-league draft.

MAJOR-LEAGUE OPPONENTS

Momen and Monte were opponents for two seasons – the first two of Clemente’s stellar career and the last two of Irvin’s truncated career in the National League. Neither was at his best. Clemente started out in 1955 at .255/.284/.382 for a 77 OPS+, albeit with some outstanding defense, as earlier noted. Irvin batted only 150 times for the Giants before being demoted to Minneapolis of the American Association, with a .253/337/.333 performance for a 79 OPS+ – a similar underwhelming offensive performance.46

In 1956 both rebounded. Clemente hit over .300 for the first of 13 times in his legendary career, ending up with a .311/.330/.431 slash line for a 106 OPS+, while Irvin, playing part-time for the Cubs (and mentoring Ernie Banks) ended up at .271/.346/.460 with a 116 OPS+, a decent career-ending result. More interesting, though, is that five of Clemente’s 12 home runs combined in his first two seasons, were against Irvin’s team, with Irvin missing the second half of the 1955 season’s games against Clemente due to his demotion.47

Clemente’s first major-league home run came on April 18, 1955, at the Polo Grounds in front of only 2,915 fans.48 In this his third major-league contest, he hit an inside-the-park home run in the fifth inning off Don Liddle of the Giants, famed for giving up the 430-plus-foot shot by Cleveland’s Vic Wertz that preceded “The Catch” by Willie Mays in Game One of the 1954 World Series. Clemente went 2-for-4 and drove in Pittsburgh’s second run with a sacrifice fly. Irvin played as well, going 1-for-4 with a double, a sacrifice fly, and two RBIs as Pittsburgh lost its sixth straight game to start the season, 12-3. In their first contest playing against each other, both got off to flying starts!49

Clemente hit a 430-foot triple against the Giants on May 6, scoring the tying run in a three-run rally against Johnny Antonelli as the Pirates won their sixth game in a row, 3-2, with Irvin contributing two singles and a run scored to the losing cause.50 Clemente’s third career home run also came against the Giants, a leadoff hit in a 3-2 loss at Forbes Field on May 21, with Irvin only playing as a late-inning defensive replacement.51

In 1956 Roberto Clemente had by far his best statistics against Irvin’s Chicago Cubs, with a .394/.400/.636 slash line,52 and had two especially notable games against the Cubs. On June 6 at Wrigley Field, Clemente went 4-for-4 with a home run and three runs batted in in an 8-2 victory over the Cubs. Although Irvin typically played in left field that year, he shared the position with Jim King, and in this game King was playing in left field when Clemente launched his fifth-inning drive over the left-field fence. Irvin did provide a pinch-hit single to the losing cause.53

In the other game, on July 25 at Forbes Field, Clemente performed a feat that had never been done before in major-league baseball – and has never been done since.54 In the bottom of the ninth inning, with nobody out, the bases loaded, and the Pirates losing 8-5, Clemente faced relief pitcher Jim Brosnan, who had just been brought into the game. On the first pitch, a slider high and inside,

Clemente drove it against the light standard in left field. Jim King had backed up to make the catch but it was over his head. The ball bounced off the slanted side of the fencing and rolled along the cinder path to center field. Here came Hank Foiles, Bill Virdon, and then Dick Cole, heading home and making it easily. Then came Clemente into third. Bobby Bragan had his hands up – stretched to hold up his outfielder. The relay was coming in from Solly Drake. But around third came Clemente and down the home path. He made it just in front of the relay from Ernie Banks. He slid, missed the plate, then reached back to rest his hand on the rubber with the ninth run in a 9-8 victory as the crowd of 12,431 went goofy with excitement.55

In 2015 poet Martin Espada wrote about Clemente’s home run and the reaction to it by manager Bragan and the various media commentators, including the pitcher who gave up the only inside-the-park, walk-off grand slam (ITPWOGS) in major-league history, Jim Brosnan. While discussing how Clemente disobeyed his manager and arguably made “a fundamental error – trying to score a run on a potentially close play with no one out,” Espada argued that Brosnan’s critique was not only an example of stereotyping – but it was also fundamentally wrong.

For Brosnan, writing a scouting report on the Pirates for Life in advance of the 1960 World Series, the Clemente home run, which in his words “excited the fans, startled the manager, shocked me, and disgusted my club,” was an example of Clemente’s “Latin-American variety of showboating.”56 Instead, Espada argued that “to accomplish his unprecedented feat, Clemente had to make a number of split-second calculations involving the dimensions of the ballpark, the path traveled by the baseball after it struck the light standard, the position of the outfielders, the accuracy of the relay throws, his own speed around the bases, and his manager’s gestures to halt, which he ignored because he knew that his instantaneous calculations were correct.”57

Were Clemente still alive, he would undoubtedly say that his play in the 1971 World Series was his greatest thrill in baseball, not his unique ITPWOGS. But to the end of his long life, Monte Irvin would say that his greatest thrill in baseball was his straight steal of home in the first inning of the first game of the 1951 World Series against the New York Yankees.58 Unlike Clemente’s daring dash to home plate, Irvin’s steal was given the green light by manager Durocher, coaching at third, and it occurred with two outs in the first inning, when Irvin noticed that Yankees pitcher Allie Reynolds was “taking a long time to deliver the ball. He was ducking his head and going into that long pumping motion before he let go of the ball.”59 Reynolds was clearly surprised, and threw high to catcher Yogi Berra, enabling Irvin to successfully complete the first straight steal of home in a World Series game in 30 years.60

In his autobiography, Irvin speculated that his steal “might have embarrassed the Yankees a little.”61 Clearly, based on his reaction, Jim Brosnan was more than a little embarrassed by Clemente’s successful tour of the bases on July 25, 1956, which was his second career inside-the-park home run, both against Irvin’s teams.

Irvin’s play, the sixth time he stole home in 1951, was different from Clemente’s play in that it was both practiced and deliberate (and had been approved by his manager), but it was similar in that it was an arguably low-percentage, high-excitement, thrilling maneuver that worked. Could it be that Roberto listened to Irvin’s steal of home when he was 16 years old, and later incorporated his own daring, groundbreaking play as a way to show his mentor what he had gleaned?

MOMEN AND MONTE — AS MENTORS … AND MEN

Roberto Clemente and Monte Irvin were men of different backgrounds and different temperaments. Irvin was more of a “go along to get along” individual. Although he did express himself openly about racism, he was a relatively quiet and cooperative teammate, and later assistant to Commissioner Bowie Kuhn, breaking ground as the first Black baseball executive in the formerly White major leagues. As a groundbreaking Black and Latin superstar, Clemente faced racism and language/cultural adaptation difficulties, and he spoke of them openly and loudly. Both were parts of significant moments in baseball’s integration. Irvin was the first Black New York Giant in 1949 with Hank Thompson, and in the first all-Black outfield with Thompson and Willie Mays in the 1951 World Series. Clemente played in the first all-Latino outfield, with Puerto Rican Carlos Bernier and Cuban Ramon Mejias, during spring training of 1955,62 and was part of the first all-Black starting nine for the Pirates in 1971.

Each man became celebrated for his humanity. This author, who has been researching Irvin’s life and career for many years, has come across no one with anything bad to say about Irvin as a human being. In contrast, Clemente was often criticized – but by the end of his short and eventful life, he had become celebrated as a great humanitarian.

Despite different methods, both Momen and Monte were mentors. One of Irvin’s first subjects was in fact Roberto himself. Whether or not Irvin truly was aware of young Roberto, he had a great impact on Roberto’s baseball development. Later, Black pitcher Brooks Lawrence, as quoted by Jim Brosnan – yes, the very same man who critiqued Roberto’s “showboat” style of play – said that “Monte was the Black player all the other Black players looked up to. Jackie Robinson was aloof to them, while Irvin was willing to help. So while they idolized Jackie, they loved Monte. Lawrence explained, ‘I want my idols to talk to me.’”63

Roberto Clemente’s life was replete with instances where he helped others – teammates and even sometimes opponents – to perform better, or just to be ready to compete. For example, in 1966 Matty Alou joined the Pirates and proceeded to win his first (and only) batting title. Clemente, speaking to Alou in Spanish, had exhorted him to hit to left and stationed himself at third base during batting practice to get Alou to hit to him. Pirates manager Harry Walker, in describing Clemente’s principal role in Alou’s transformation and success, said, “Clemente has his critics, but no man ever gave more of himself or worked more unselfishly for the good of the team than Roberto.”64 Longtime teammate Al Oliver not only called Clemente “my biggest booster,”65 but also expressed that “he was the biggest inspiration of my career, and he was an inspiration to all the rest of the members of the team.”66 Even longtime opponent Bobby Bonds was helped by Clemente in 1972 when he noticed that Bonds was slowing down when fielding routine plays: “Clemente felt motivated to talk to Bonds in 1972. Clemente stressed to the young Bonds the importance of playing hard at all times.”67

CONCLUSION-EPITAPHS

In Roberto Clemente’s Hall of Fame player file, there is a typewritten document entitled “Epitaph.” A handwritten notation says “Interview July 1971.” Of course, Clemente did not know he would be dead in less than two years – although he had premonitions of an early death. In the document, Clemente stressed the importance of always playing hard, just as he underscored with Bobby Bonds. He also said, “I believe the kids must have idols. A country without idols is nothing.… I do it for baseball [give out 2,000 autograph cards to kids] because baseball has given me a good life.… I get mad, but I do not hate. I raise my voice when I speak. That is the way I am. But I do not hate.”68

In the immediate aftermath of the plane crash that took Clemente’s life, Commissioner Bowie Kuhn, among many others, spoke eloquently of Clemente’s legacy: “Somehow Roberto transcended superstardom.… (H)is marvelous playing skills rank him among the truly elite.… And what a wonderfully good man he was. Always concerned about others. He had about him the touch of royalty” (emphasis added).69 And at the Hall of Fame induction for both men on August 6, 1973, Kuhn spoke similarly about Irvin: “[N]ever … has baseball produced a kinder, more decent, more beloved man, nor one who has meant more to me personally, than Monte Irvin.70

And what did Monte Irvin have to say about Clemente, near and at the end of Clemente’s life? In his autobiography, he wrote, “[W]e used to communicate with each other often and he and I became real close until the day he died.”71 And when he heard Clemente express how much he idolized Irvin as a youngster, he said, “If I had anything to do with Roberto becoming a baseball player, or becoming involved with baseball … I think that my life in baseball is complete.”72

According to Roberto Clemente’s oldest son, Roberto Jr., Irvin certainly had quite a bit to do with his father’s success: “(T)he man was a gem … and he did not know – Monte really did not know – how much he had to do with Dad and how much of an impact he had on Dad.”73 In living, and expressing, their concern for and continual efforts to help others, both Momen and Monte, each a baseball pioneer, lived lives that fulfilled Jackie Robinson’s epitaph: “A Life Is Not Important Except in The Impact It Has on Other Lives.”

DORON “DUKE” GOLDMAN is a longtime SABR member who specializes in the Negro Leagues and the process of baseball integration. Duke began to idolize Roberto Clemente as a 9-year-old watching Clemente dominate the 1971 World Series with his unbelievable arm and all-around dazzling performance.

Notes

1 http://www.retrosheet.org pitcher-batter matchups, accessed March 28, 2022. Clemente far exceeded his .317 lifetime batting average against Spahn – noteworthy in that Spahn was far from an ordinary pitcher. His home run, walk, and strikeout totals against Spahn were more closely in line with his lifetime percentages.

2 Phil Musick, Who Was Roberto? A Biography of Roberto Clemente (Garden City, New York: Doubleday & Company, Inc. 1974), 59.

3 David Maraniss, Clemente: The Passion and Grace of Baseball’s Last Hero (New York: Simon & Schuster, Advanced Reader’s Edition 2006), 21.

4 Maraniss, 21.

5 Sam Nover, “A Conversation with Roberto Clemente,” WIIC TV, October 8, 1972, www.youtube.com/watch?v=Pe-KQ15vWOA.

6 See Jake Crouse, “The HOFer Who Inspired a Young Clemente,” www.mlb.com, February 24, 2022. https://www.mlb.com/news/roberto-clemente-inspired-by-negro-leaguer-monte-irvin, accessed March 29, 2022. (Clemente using a bicycle to “trek to San Juan to watch Puerto Rico’s Winter League”); Maraniss, 25 (“Clemente sometimes had a quarter from his father. He used a dime for the bus and fifteen cents for a ticket” to get to San Juan.)

7 Maraniss, 25.

8 Thomas E. Van Hyning, Puerto Rico’s Winter League: A History of Major League Baseball’s Launching Pad (Jefferson, North Carolina: McFarland & Company, 1995), 89.

9 Monte Irvin, Nice Guys Finish First: The Autobiography of Monte Irvin (New York: Carroll & Graf Publishers, 1996), 42-43.

10 Van Hyning, 89-90.

11 Van Hyning, 89. (“Irvin also filled in at the other infield positions and saw limited duty in the outfield.”)

12 Musick, 59.

13 Baseball-Reference.com, Monte Irvin page, accessed March 29, 2022.

14 Irvin, 117.

15 Irvin batted .3677 to Pedroso’s .3684, but batted 155 times to Pedroso’s 95. Van Hyning, 89.

16 Van Hyning, 89.

17 Bill Nunn, Jr., “CHANGE OF PACE: Scribes Now Rate Clemente as ‘Best,’” New Pittsburgh Courier, February 24, 1962: 28.

18 Les Biederman, “Clemente, Early Buc Ace, Says He’s Better in Summer,” The Sporting News, June 29, 1955: 26. The number of 55 games comes from Retrosheet.org.

19 Nathalie Alonso, “Revisiting Roberto Clemente’s Best Moments,” www.mlb.com December 31, 2021, https://www.mlb.com/news/roberto-clemente-greatest-moments, accessed March 29, 2022. Clemente led right fielders in assists six times. Baseball-Reference.com Appearances on Leaderboards, Awards, and Honors.

20 Baseball-Reference.com, Appearances on Leaderboards, Awards, and Honors.

21 Michael Humphreys, Wizardry: Baseball’s All-Time Greatest Fielders Revealed (New York: Oxford University Press, 2011), 42 (Clemente) and 207 (Irvin).

22 Irvin, 26-27.

23 Ira Miller, Roberto Clemente (New York: Grosset & Dunlap Publishers, 1973), 13.

24 Bruce Markusen, Roberto Clemente: The Great One (Champaign, Illinois: Sports Publishing Inc., 1998), 8.

25 Maraniss, 25.

26 Roberto Clemente: A Touch of Royalty, www.youtube.com/watch?v=oKIRDgmwg8w, accessed March 30, 2022.

27 Roberto Clemente: A Video Tribute, www.youtube.com/watch?v=PnyDAZZI7Ipk, accessed March 30, 2022.

28 Email from Stew Thornley to author, February 10, 2022.

29 Maraniss, 25.

30 Irvin, 221.

31 Irvin, 221. The author has spent considerable time trying to parse the tenses and intentions of various statements of Irvin’s and of authors either quoting or characterizing Roberto Clemente’s early involvement with Monte Irvin to determine definitively if he knew who Roberto Clemente was in 1945 – concluding that it is likely that Irvin did not remember Clemente clearly after their early encounters.

32 Maraniss, 25.

33 See e.g. Irvin, 119-120. The full story is much more complicated but not relevant to this article.

34 Irvin, 123.

35 Maraniss, 26-27.

36 Clemente had been signed by Santurce in 1952.

37 “Giants Had First Chance at Clemente, Nixed Price,” The Sporting News, November 26, 1966: 26. According to Markusen, Giants scouts noted that Clemente was an undisciplined hitter and Stoneham became concerned that Clemente would strike out too frequently. Markusen, 15.

38 Maraniss, 37.

39 Baseball-Reference.com, Roberto Clemente page, accessed March 30, 2022.

40 “Sukey First to Glimpse Clemente,” The Sporting News, June 29, 1955: 26. It is worth mentioning that Sukeforth likely scouted Monte Irvin for the Dodgers in 1945 and perhaps earlier as a potential pioneering Black player for the Dodgers.

41 Brent Kelley, Baseball’s Biggest Blunder: The Bonus Rule of 1953-1957 (Lanham, Maryland: Scarecrow Press, Inc. 1997), 20.

42 The Sporting News, May 25, 1955: 11.

43 Les Biederman, “Hats Off ! Roberto Clemente,” The Sporting News, June 20, 1956: 19.

44 Perhaps Bavasi in 1955 forgot that when the Royals signed Clemente, Mays had just missed most of the past two years in the military, and had yet to truly prove himself a superstar, although Irvin was about to turn 35 at the time of Clemente’s signing and Mays certainly showed enormous potential in 1951.

45 Whitney Martin, “The Sports Trail,” Bedford (Pennsylvania) Gazette, June 29, 1955: 4.

46 Baseball-Reference.com, Roberto Clemente and Monte Irvin pages.

47 Clemente Home Run Log, Compiled by Joseph A. Mercurio, Roberto Clemente player file at the National Baseball Hall of Fame. Clemente hit three of his five home runs against the Giants in 1955, but the third was hit after Irvin had been sent to Minneapolis.

48 Baseball Reference.com Game Logs for Roberto Clemente 1955, accessed March 30, 2022. It is noteworthy that the Giants drew very few fans in an early-season game in the year following their four-game World Series sweep of the Cleveland Indians, an indication that trouble was ahead for the Giants (and their fans) as a New York entity.

49 “Willie Hits Two Triples and Single,” Washington Post, April 19, 1955: 27.

50 “Pirates 3 In 7th Upset Giants 3-2,” New York Times, May 7, 1955: 11.

51 Baseball-Reference.com Game Logs for Roberto Clemente 1955.

52 Baseball-Reference.com Game Logs for Roberto Clemente 1956.

53 Baseball-Reference.com Game Logs for Roberto Clemente 1955.

54 It is certainly possible that Clemente’s feat was performed in the Negro Leagues, whose league play between 1920 and 1948 has been recognized as major league.

55 Pittsburgh Post-Gazette, July 26, 1956, cited in Martin Espada’s “The Greatest Home Run of All Time,” The Massachusetts Review, Volume 56, Number 2, Summer 2015: 249-255. Note that Monte Irvin was not playing left field in that game.

56 Espada. Quotes from Brosnan cited by Espada appeared in Life magazine, October 5, 1960.

57 Espada.

58 Irvin, 164.

59 Irvin, 164. See https://sabr.org/gamesproj/game/october-4-1951-monte-irvin-steals-home-as-giants-take-game-1-over-yankees/.

60 Andrew Heckroth, “October 4, 1951: Monte Irvin Steals Home as Giants Take Game 1 over Yankees,” Games Project, www.sabr.org accessed March 31, 2022.

61 Irvin, 163.

62 The Sporting News, March 23, 1955: 34. Note that the article incorrectly called it an all-Puerto Rican outfield.

63 Danny Peary, ed., We Played the Game: 65 Players Remember Baseball’s Greatest Era 1947-1964 (New York: Hyperion, 1994), 319.

64 Arthur Daley, “A Matter of Value,” New York Times, December 16, 1966. Clipping in Clemente Hall of Fame player file.

65 “Memory of ‘Great One’ Inspires Bucs Still,” Philadelphia Inquirer, April 7, 1973.

66 “What Clemente Meant to the Pirates,” from unidentified newspaper 1973. Clipping in Clemente Hall of Fame player file.

67 Bruce Markusen. “#Card Corner: 1981 Fleer Bobby Bonds,” www.baseballhall.org, accessed March 27, 2021.

68 Document entitled “Epitaph” in Clemente Hall of Fame player file.

69 Associated Press, “Baseball Respected Clemente as Greatest, ‘Super Star,’” Beaver Falls (Pennsylvania) News Tribune, January 2, 1973.

70 New York Times, August 7, 1973.

71 Irvin, 221.

72 Roberto Clemente: A Touch of Royalty.

73 Crouse, “The HOFer Who Inspired a Young Clemente.”