Movies, Mentors, and the Minor Leagues

This article was written by David Krell

This article was published in The National Pastime: Major Research on the Minor Leagues (2022)

The mentor-mentee relationship is a bedrock of Hollywood storytelling: Dr. David Zorba and Dr. Ben Casey. Obi-Wan Kenobi and Luke Skywalker. Mr. Miyagi and Daniel LaRusso. Mickey Goldmill and Rocky Balboa. Three movies and one TV-movie set in baseball’s minor leagues exemplify the dynamic.

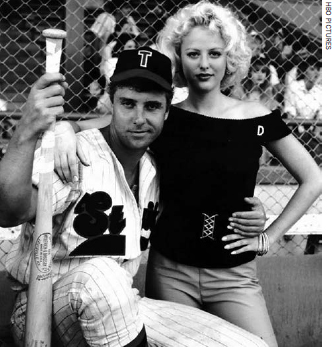

Stud Cantrell (William Petersen) and Dixie Lee Boxx (Virginia Madsen) from Long Bone. (HBO Pictures)

LONG GONE: STUD CANTRELL AND JAMIE DON WEEKS

“I never made it, kid. But I would’ve. Goddammit, I would’ve.”

So says the Tampico Stogies’ player-manager Cecil “Stud” Cantrell in the 1987 HBO TV-movie Long Gone, set in the Alabama-Florida League during the 1957 season.1 Cantrell’s revelation of mourning and confidence to milk-drinking, church-going rookie Jamie Don Weeks punctuates his tale about competing with Stan Musial for the left fielder position on the St. Louis Cardinals roster. After four years of success in the minor leagues, Stud anticipated challenging Musial upon reaching the majors. “He had a prettier swing than me,” explained Stud. “But I hit the ball harder. And batted both ways.”

But America’s entry into World War II led to Stud joining the Marines, getting wounded at Guadalcanal, and failing to be at the physical peak required to compete in the major leagues. A Class-D league team in Tampico, Florida, will apparently be his last stop in his baseball career, and he takes young Jamie under his wing.

Stud’s mentoring of Jamie goes beyond the foul lines. He teaches Jamie that women are useful only for their service to men: women should satiate their cravings, bind their wounds, and support their dreams. Enter Dixie Lee Boxx, a blonde bombshell and beauty queen—Miss Strawberry Blossom—who falls for Stud but has equal amounts of affection and grit. Jamie begins to date Esther Wrenn, a religious sort; their encounters end in the backseat of a car.2

The depth of Stud’s influence on Jamie is visible. At the local diner where the team congregates for breakfast, Stud is recounting the recent exploits of the Tampico nine when Jamie—to Stud’s surprise—enters as a carbon copy of his idol in clothing, swagger, and a fast-talking manner. But it goes further than looking and sounding like Stud. When Jamie finds out that Esther is pregnant, he takes a page out of the Stud Cantrell Playbook and ignores her feelings. She runs away to have the baby at an aunt’s in Mobile so no one in Tampico will know the truth.

It’s not the only moral dilemma. Stud also gets bribed. A plum job awaits him—managing the Dothan Cardinals next season—if he sits out the season-ending Dothan-Tampico game in order to hand the pennant to his future employer. Joe Louis Brown (a Black player whom Stud labels José Brown from Venezuela to try to avoid the violence and prejudice against Blacks in the Deep South) is seduced by the promise of wealth; Dothan’s ball club gives him a Cadillac.

When Dixie Lee reveals the plot to Jamie, feelings of betrayal, anger, and alienation erupt. He confronts Stud, to no avail. In the locker room before the game, Jamie steps into the leadership void to decide the lineup, covering for the backstabbing skipper by saying that Stud is “sick as a dog.” Brown is also nowhere to be found, but Jamie reminds his teammates that they can beat Dothan without their star players, emphasizing that they won games when Stud and Joe went oh-for-four.

In the middle of the game, however, the duo shrug off their craven decision and appear at Henley Field. Stud, of course, comes to bat in the bottom of the ninth, with the game tied and the bases loaded. Stud is 2-for-68 against the pitcher, Dusty Hoolihan. He purposely taunts Hoolihan with disgusting comments about Dusty’s sister. It’s a last resort, but it works. Stud gets beaned in the head—and the game-winning RBI.

But there’s more than a “W” for the veteran and his underling—they have undergone a catharsis.

Stud asks Dixie to marry him; Jamie heads to Mobile to find Esther; and their double wedding takes place on the baseball diamond. It’s a logical site given the importance of the Stogies to Stud’s and Jamie’s character arcs, each laced with immaturity at the beginning and concluding with self-realization.

William Petersen plays Stud. “He’s found himself a nice, safe place,” explains the actor, who later starred in the long-running CBS show CSI. “He’s found a way to cope without the heartbreak, the feeling of failure. Why I think he’s a great character is that he doesn’t dwell on it, but he doesn’t want to share it and be vulnerable. Dixie sees that in him and allows him to become a success. I think the movie’s very much about a man growing up.”3

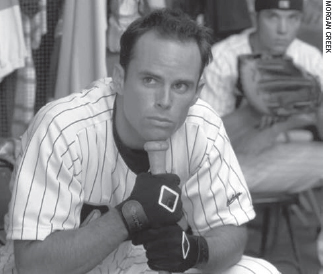

Walton Goggins plays Billy “Downtown” Anderson in Major League: Back to the Minors. (Morgan Creek)

MAJOR LEAGUE: BACK TO THE MINORS: GUS CANTRELL AND DOWNTOWN ANDERSON

Major League: Back to the Minors begins with Gus Cantrell—no relation to Stud—an aging pitcher trying to eke out a win for the Fort Myers Miracle. After the game, his old friend Roger Dorn approaches him with a challenging task. Dorn owns the Minnesota Twins and needs a seasoned pro to manage the Buzz, a Triple-A team in the Twins farm system.

There’s one standout player on the ballclub in this 1998 film, the third in the Major League franchise. Billy “Downtown” Anderson can crush the ball, and his ego is just as powerful as his swing. Downtown believes that being a pull hitter is sufficient, but Gus knows better. He watches a Buzz game from the stands while mulling over the offer.

Downtown has a splendid afternoon. When they meet, Downtown teases that he had triples of Gus’s rookie card and traded them for a player to be named later. It stings. Gus takes the Buzz job and warns him that major league pitchers will quickly learn to pitch around his strength. The rookie fares none too well upon his call-up—his struggles are noted on a Twins broadcast as going 3-for-15 before he’s sent back to the Buzz.

Humbled, he apologizes to Gus for his attitude and admits that the manager’s forecast came true. Gus tutors Downtown on batting strategy and hitting mechanics to maximize taking the ball to the opposite field. The proof that Downtown has become a well- rounded threat is shown when he wins an exhibition game against the Twins with a two-run homer.

As with Long Gone, the rookie is not the only one to learn something about himself in Major League: Back to the Minors. Although when the Buzz beat the Twins, Gus also won a bet with Twins manager Leonard Huff, Gus refuses to accept his bounty— Huff’s job—because he realizes that his happiness in baseball is helping younger players develop their skills.

“He was really a combination of coaches I had growing up and the kind of a coach that you always would like to have and I create that ideal coach,” said Scott Bakula, about playing the role of Gus.4

Roy Dean Bream (William Russ) tutors Tyrone Debray (Glenn Plummer) about pitching in Pastime. (Miramax)

PASTIME: ROY DEAN BREAM AND TYRONE DEBRAY

Pastime revolves around Roy Dean Bream, a 41-year- old pitcher for the Tri-City Steamers. (The California cities of Clinton, York, and Vidalia are the setting for this 1957 period piece.) Played by William Russ—who had a breakout role as fictional government operative Roger LoCoco on a 1988 story arc in Wiseguy on CBS— Bream has an exuberance that is not always shared by his teammates. “On a spiritual level he is very advanced,” explained Russ. “He has a nice karmic code. It’s like a certain kind of guru; he understood life through baseball.”5

Tyrone Debray is the shy rookie whom Roy Dean takes under his wing. Among the lessons imparted: how to throw the curveball nicknamed “Bream Dream” and the importance of looking a man in the eye while talking. Roy Dean’s badge of baseball honor is a cup of coffee with the Chicago Cubs—a single appearance resulting in a Stan Musial grand slam. His other revelation: he is only six games behind third place for most lifetime pitching appearances in baseball; Cy Young and Walter Johnson occupy the first two slots.

After learning at a team party that he will soon be released, Roy Dean goes to Tri-City Stadium to exorcise his sadness. He suits up and takes out his frustration by throwing at a tarp hung on the backstop fence with a strike zone painted on it. Emotional and physical pain soon give way to elation.

Tyrone searches for Roy Dean and finds him prone on the mound—dead. He had high blood pressure, which Tyrone learns when he finds medication in Roy Dean’s home. Except for Tyrone and Steamers manager Clyde Bigby, nobody from the team attends the funeral because there’s a game at the same time. Tyrone and his skipper arrive late to the ballpark after paying their respects.

Conflict arises, but it has nothing to do with tardiness. Steamers hurler Randy Keever has been a thorn in Tyrone’s side, presumably because the rookie is Black. Clyde sends Tyrone to relieve Randy in the second inning of a 4-4 game; Randy mocks the rookie and says with sarcasm that he should win the game for Roy Dean. No longer shy and withdrawn, Tyrone finds his strength and looks Randy in the eye just like his tutor taught him. Then, they fight; Tyrone dominates. Clyde prevents the players from interfering until the umpire tells him to break it up, then fires Keever.

When Tyrone faces his first batter, he grips the ball the way Roy Dean taught him. The camera pans to a clear, blue sky and slowly drops to reveal Comiskey Park and Tyrone pitching for the White Sox with a stare indicating a serious competitor. He has grown into a major leaguer thanks to his mentor.

Tim Robbins as “Nuke” LaLoosh and Kevin Costner as “Crash” Davis in Bull Durham. (Orion Pictures)

BULL DURHAM: CRASH DAVIS AND NUKE LALOOSH

Ebby Calvin “Nuke” LaLoosh has a thunderbolt for a right arm. So says perennial minor-league catcher Crash Davis, who earns admiration from fellow members of the Class-A Durham Bulls upon revealing that he once spent three weeks in the major leagues. “Twenty-one greatest days of my life,” says the veteran in the 1988 movie Bull Durham.

Crash gets a mandate from the Bulls’ unnamed parent club—which has bought Crash’s Triple-A contract— to tutor Nuke, who has tremendous speed but lacks control. In his professional debut, Nuke racks up 18 walks and 18 strikeouts—both league records. Endurance is evident; Nuke’s last five pitches of the game were faster than his first five. It’s a battle between the seasoned veteran and the cocky newcomer.

However, there’s another mentor for the fireballer. Annie Savoy, a youthful woman belying her age (seemingly around 40), has an annual tradition: take a younger player under her wing and instruct him on the finer points of romance and lovemaking and improving his baseball skills. “There’s never been a ballplayer slept with me that didn’t have the best year of his career,” declares Annie in a voiceover at the beginning of the film.6 The dual nature of Nuke’s two mentors in the film emphasizes the way in which all of the baseball-playing lessons serve as analogies for the personal growth experienced by the characters.

Nuke’s brashness fades when he realizes Crash’s value during a winning streak. Once dismissive, he grows eager for lessons. But Crash doesn’t just give pitching tips. He underscores the importance of being modest and vague during interviews because he sees that Nuke has terrific potential, but a brazen persona can be just as destructive as a fastball that lacks control. Self-discipline is the key to success. Crash schools Nuke on the clichés; we hear Nuke repeat them to a reporter after he gets promoted at the end of the movie.

But while the rookie’s growth is predestined, what about his mentors? Crash has a noteworthy achievement that he wishes not to highlight—career minor-league home-run record. He sees it as proof he never had a sustained career in the show and doesn’t wish to see it highlighted in the press.

Indeed, the inability to reach the “promised land” is a solemn undercurrent to Bull Durham. Thousands of minor leaguers never cross the threshold to the majors; it’s a paradigm exemplifying Henry David Thoreau’s observation that quiet desperation is the lot of most men. During the film’s 30th anniversary, Costner said that Mickey Mantle called the story “sad” when the Hall of Famer appeared on a talk show coinciding with the original release.7 But Crash neither devalues his station nor degrades himself. “What’s important to my character is that it wasn’t beneath him to play down there in Durham,” explained Costner.8

After Nuke’s promotion, the parent club releases Crash. Annie and he had a growing mutual attraction throughout the film; they consummate their carnal feelings in a passionate night. Crash sneaks out in the morning, heading for a new opportunity with the Asheville Tourists, where he breaks the home-run record.

To Annie’s surprise, though, Crash returns with a declaration. He’s quitting playing and thinking about being a manager. She responds that she’s quitting young men. They’re both ready to move on to the next stage of their lives—not the major leagues, but something better—and they dance together in Annie’s living room as the credits roll.

Ron Shelton wrote and directed Bull Durham. A former minor leaguer, he started in the Appalachian League and reached Triple-A before starting a screenwriting career. “Crash Davis loves something more than it loves him back,” said Shelton in 2020. “It happens to be a game and he’s really good at it. He’s just not in the right place at the right time. And everybody loves something, a job, a woman, a man, something, more than it loves them back. And that’s why I think the movie’s hung around.”9

CONCLUSION

The somewhat claustrophobic nature of the minor leagues adds weight to the character portrayals in these films. Players are often stuck, never getting beyond the confines of smaller cities. We never know if Jamie Don Weeks can go past Tampico for greater glory. It’s likely that Downtown Anderson does after additional tutoring from Gus. Nuke LaLoosh and Tyrone Debray make it to the Show. But their emotional journeys are equally strong. The minor leagues make the perfect milieu to explore this type of character development, and an apt metaphor for it.

The Hollywood trope of mentor-mentee plays out well against the backdrop of the minor leagues in all of the films discussed here. The minor leagues as a setting already provide a backdrop rich with metaphors about advancement or upward mobility in life (or lack thereof), coaching and instruction, and the juxtaposition of those graced with talent and others surviving on pure grit. Professional baseball is a largely masculine milieu, and the small-town locales and period-piece settings create ample opportunities for the filmmakers to comment on topics ranging from love and women to race relations and fairness: all good topics for real-life mentors, not just Hollywood ones.

DAVID KRELL is the author of 1962: Baseball and America in the Time of JFK and Our Bums: The Brooklyn Dodgers in History, Memory and Popular Culture. He edited the anthologies The New York Mets in Popular Culture and The New York Yankees in Popular Culture. David’s book about 1966 will be published next year by Rowman & Littlefield. David is the chair of SABR’s Elysian Fields Chapter (Northern New Jersey).

Notes

1. Based on the 1979 novel by Paul Hemphill. A montage of the team’s epic winning streak shows a sign saying that Tampico is the home of La Madera Cigars, logically the inspiration for the team’s name. Window signs in Buchman Department Store spell the name without the apostrophe. The team is owned by the store’s owners, Hale Buchman and Hale Buchman, Jr. played by Henry Gibson of NBC’s iconic sketch comedy show Rowan & Martin’s Laugh-In (1967-73) and Teller of the magician duo Penn & Teller. A signature of their act is Teller’s silence. Long Gone is a rare speaking role for him.

2. Virginia Madsen plays Dixie and Katy Boyer plays Esther.

3. Jerry Buck, “Baseball arrives on HBO with ‘Long Gone,’” Associated Press, Desert Sun (Palm Springs, CA), May 23, 1987: F6.

4. Scott Bakula, interview with Bobbie Wygant, 1998 (date unknown), The Bobbie Wygant Archive, https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=nCTFiazn2Ms (last accessed January 21, 2022). Walton Goggins plays Downtown. Corbin Bernsen reprises his role of Roger Dorn from the first two movies in the Major League franchise.

5. Melina Gerosa, “Pastime”’s William Russ,” Entertainment Weekly, https://ew.com/article/1991/09/06/pastimes-william-russ (last accessed January 28, 2022).

6. Susan Sarandon and Tim Robbins play the Annie-Nuke coupling. It began a real-life romance that lasted until 2009, when they separated. Sarandon and Robbins have two kids together.

7. JimmyKimmeiLive!, Jackhole Industries, Aired on ABC, June 12, 2018.

8. Bob Strauss, “Costner’s game plan on target,” San Francisco Examiner, June 15, 1988: B-1.

9. Momentum, Bauer Bytes, Season 2, Episode 9, “The Origin of Bull Durham According to Director Ron Shelton,” posted October 7, 2020, https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=P6cDSm0XzFw (last accessed January 28, 2022).