Nichols Youngest to Win 300 “Kid” in More Ways than Won

This article was written by John J. O’Malley

This article was published in 1975 Baseball Research Journal

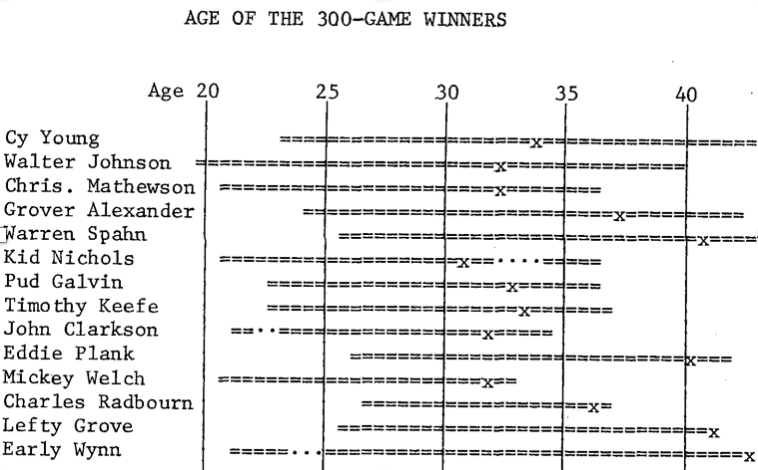

Lefty Grove, Warren Spahn, and Early Wynn– the only hurlers, to win 300 games in the last 40 years — were all relatively late starters in the race for that greatest of pitching crowns. Each amassed fewer than 90 victories prior to reaching the age of 30. Grove had 87 wins, Spahn 86, and Wynn 83 at that point in their careers. They all had passed their 40th birthdays before attaining win No. 300.

The early decades of major league baseball, however, provide us with several exceptions to that deliberate pace. John Clarkson was only 31 when he won his 300th game; so was Mickey Welch. The pitcher with the most remarkable record in his 20’s, and the most consistent, was the one they called “Kid” — Charles Augustus Nichols.

The name of Nichols evokes at best but vague memories or associations to the average fan of today, but 75 years ago, at the turn of the century, he stood in the words of the Boston Herald “second to none in the country.” The claim was no mere home-town boast, for Kid Nichols was a star from the moment of his major league debut at the age of 20 in 1890. He won 27 games for Boston that memorable year of the Brotherhood War and followed through in the next nine years with victory totals of 30, 35, 34, 32, 26, 30, 31, 31, and 21.

Eighteen of Nichols’ 21 triumphs in 1899 were achieved prior to September 14, the occasion of his 30th birthday. Previous to that date, he had won the incredible total of 294 games in his career. His last three victories of 1899 were scored on September 29, October 4, and October 13, to leave him but three short of the 300-mark going into the 1900 season. There seemed every reason to believe that those three wins would be easily attained.

With a little luck, Nichols would have won two of his first three decisions in l900. In the April 20 game against Philadelphia, Boston out-hit the Phillies 9 to 7, but five errors in the field proved the undoing of the Beaneaters as they dropped a 5to 4 decision in 11 innings. On April 24, with Duffy and Tenney missing from the lineup, Boston lost 4 to 3 to New York. Those two games, combined with a loss charged to Nichols on April 19 when he appeared in relief, left him with an 0-3 record at the end of the first week of play.

Originally scheduled to pitch again on April 26, Nichols was kept on the sidelines with what was described as a bad arm. Against his own best judgment, he took the mound on the 28th against Brooklyn, but was knocked out of the box after giving up five runs in the first inning.

On May 4, the Boston Herald reported that Nichols had aggravated a tendon strain and would be out of action for the immediate future. In the succeeding weeks, the papers were filled with speculation that Nichols’ playing career was finished. Boston manager Frank Selee issued regular statements that Nichols was as good as ever and would soon be back in the lineup with the coming of warm weather. He claimed the main problem was a siege of rheumatism perhaps brought on by the blustery weather experienced during spring training at Greensboro, North Carolina.

The diagnosis may have been correct, for on June 7 Nichols once more took the mound after a layoff of 40 days. He allowed only 6 hits in his first victory of the year as Boston triumphed over Chicago 13 to 4. Six days later, in a brilliant 3-hit shutout, Kid Nichols won his 299th game against Pittsburgh. Billy Hamilton’s homer in the third provided the only run for Boston.

Nichols’ luck turned sour again in the next three weeks as he suffered losses on June 18, 23, and 29, and July 4. Finally, on July 7, he took the mound against Chicago in what was perhaps the most important game of his career. In the top of the second with no score, two out, and the bases loaded, Nichols came to bat in his own cause. He hit a grounder which was fumbled by the Chicago shortstop Clingman, with Lowe scoring on the play. The roof then caved in on pitcher Jim Callahan as Hamilton singled, Collins doubled, Stahl singled, and Tenney doubled – seven runs scoring in the inning.

Play was suspended at that point as rain deluged the field. It soon let up, however, and the game was resumed. Despite two doubles by Bradley in the early innings, and an eighth inning home run by Greene, Chicago was never in the game thereafter as Boston romped to an 11 to 4 victory. The box score:

|

Boston |

|

AB |

R |

H |

|

Chicago |

|

AB |

R |

H |

|

Hamilton |

CF |

5 |

2 |

2 |

|

McCarthy |

LF |

5 |

0 |

1 |

|

Collins |

3B |

4 |

2 |

2 |

|

Childs |

2B |

5 |

0 |

2 |

|

Stahl |

LF |

5 |

1 |

2 |

|

Mertes |

lB |

5 |

0 |

4 |

|

Tenney |

lB |

5 |

0 |

3 |

|

Ryan |

RF |

4 |

0 |

1 |

|

Freeman |

RF |

5 |

0 |

1 |

|

Greene |

CF |

3 |

2 |

1 |

|

Lowe |

2B |

5 |

1 |

3 |

|

Clingman |

SS |

4 |

0 |

0 |

|

Long |

SS |

5 |

1 |

2 |

|

Bradley |

3B |

4 |

1 |

2 |

|

Clarke |

C |

3 |

2 |

2 |

|

Donahue |

C |

4 |

0 |

0 |

|

Nichols |

P |

5 |

2 |

2 |

|

Callahan |

P |

3 |

1 |

0 |

|

|

|

42 |

11 |

19 |

|

|

|

37 |

4 |

11 |

|

Boston |

0 |

7 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

3 |

0 |

1 |

0 |

|

11 |

|

Chicago |

0 |

2 |

1 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

1 |

0 |

|

4 |

Left on bases-Chicago 9, Boston 7. Two base hits-Bradley 2, Collins, Lowe, Tenney. Home run-Greene. Sacrifice hit-Collins. Stolen bases-Greene, Tenney. Double plays-Mertes and Clingman; Lowe, Long and Tenney. Struck out-by Nichols 2. First base on balls-off Callahan 1, off Nichols 2. Hit by pitcher-by Nichols 1, by Callahan 1. Time-2 hours, 12 minutes. Umpire-O’Day. Attendance-4 ,000.

Nine months and 23 days past his 30th birthday, Nichols stood then the youngest man ever to win 300 games in the majors. That record remains to this day. Nichols would win 10 games during the 1900 season and 19 the following year. That was his final season for Boston, for shortly before the 1902 campaign began, Boston fans received some startling news from Kansas City. Nichols had accepted the post of player-manager of the Kansas City entry in the Western Association. Boston subsequently agreed to his release.

Returning to the majors with the St. Louis Cardinals in 1904, Nichols was both manager and premier pitcher. He won 21 games, completing all 35 of his starts. He was down to 11 wins the next year and early in 1906 he called it a career at age 36.

Most encyclopedias and baseball record books give Nichols 362 major league wins, but a review of each box score plus assistance from baseball historians Cliff Kachline and Leonard Gettelson, indicates the corrected total should be 361 wins and 208 losses. The two games in contention were: (1) the August 12, 1895, contest with Washington which was credited as a win for Nichols. On review, however, league officials found that the umpire erred in the first inning in calling a Washington batter out for batting out of order. All totals of-the game were there-upon thrown out, and record books reflect this; (2) the July 4, 1898, game which Willis started for Boston against New York. Nichols relieved Willis in the bottom of the eighth with the bases loaded, none out, and the score 6-2 in favor of Boston. Three additional runs were scored by New York to reduce the margin to 6-5. That was the final score and Willis obviously should have the win instead of Nichols.

Aided by the 20-20 vision of hindsight, we can see that Nichols’ decision to pitch for Kansas City in 1902 and 1903 probably kept him from winning 400 games in the majors. In his two years there he won 48 games and he still had plenty of “stuff” as reflected by his 21 wins for the Cardinals in 1904. So, while Nichols did not attain the win standards of Cy Young or Walter Johnson, he nevertheless remains one of the five grandmasters of 19th Century pitching with Tim Keefe, John Clarkson, Charles Radbourn, and Young, who was equally impressive both before and after 1900. Inclusion in that company is perhaps honor enough for Nichols.