Observations of Umpires at Work

This article was written by No items found

This article was published in Spring 2011 Baseball Research Journal

PREFACE

By Tom Larwin

This article is a summary of observations from seven individuals who watched a ball game in an unusual way: We watched the umpires—the umpires only—and not the players. Our observations and resulting viewpoints were augmented the following day in an informal meeting with two of the umpires, who discussed certain aspects of the game with us.

The resulting article is a composition of these seven viewpoints. The writing styles are different and reflect the authors’ individual and differing views of the umpire team as the game transpired. During the game the focus—the entire focus—was on each of the four umpires and their individual behavior and actions while on the field. For each of us, the game and the final score were secondary for the first time ever while watching a major league baseball game.

There was no attempt to restrict the observations to key plays, or controversial decisions. In fact, other than the home plate umpire, most of the individual umpires’ actions were seemingly insignificant, and not involved in making a call. On any particular play most fans watching the game action would pay no attention to any of the umpires or what they might be doing … until it’s time to make a call.

Certainly much of what the umpires have to do during the game can be considered routine, and from that point of view we did not uncover many significant revelations.

Taken as a collective experience, however, over the course of an entire game, watching the umpires perform brought us a heightened appreciation for what they do on the field for two-and-half to three hours or more during every major league game.

INTRODUCTION

By Tom Larwin

Despite his role, the umpire is the most neglected, least appreciated, and most misunderstood participant in the National Pastime.[fn]Gerlach, Larry R., The Men in Blue, Conversations with Umpires (New York: The Viking Press, 1980), viii[/fn]

— Larry GerlachThe cardinal rule of umpiring is to follow the ball wherever it goes.[fn]Gerlach, 201.[/fn]

— Shag Crawford, NL Umpire (1956–75)

On September 10, 2010, the San Diego Ted Williams SABR Chapter had a unique opportunity to benefit from unprecedented access to Major League Baseball (MLB) umpires. MLB Umpire Crew Chief Jerry Crawford gave his approval to a Chapter project that would involve an in-depth examination of his four-umpire crew during the conduct of a baseball game.

As an umpire you can’t really appreciate a ballgame. You have to concentrate so much on your job that you don’t enjoy the game. I said many times that when I got out of umpiring, I wouldn’t go near a ball park as long as I lived. But I have. Still, I look at the umpires, not the ballplayers. I can’t help it. I get a big kick out of watching the umpires, anticipating what they are going to do.[fn]Gerlach, 73.[/fn]

— Joe Rue, AL Umpire (1938–47)

THE PROJECT

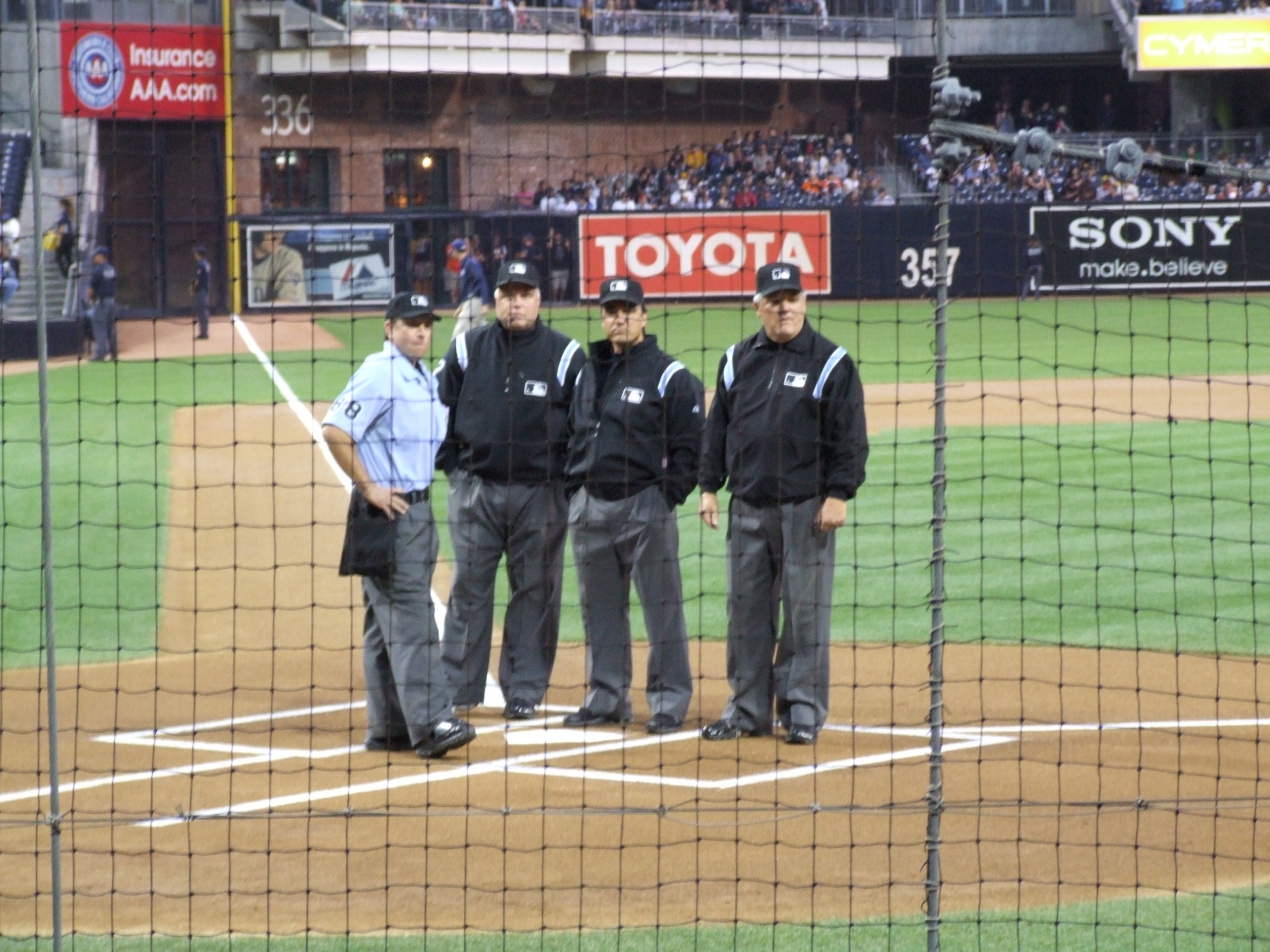

The intent of the project was to observe and document each of the four umpires throughout the playing of a baseball game, beginning with their pre-game meeting at home plate and continuing through their exit from the field following the final out.

Umpires are usually ignored by the casual fan. It’s often said that a well-umpired game is one in which you don’t even remember seeing the umpires. “Let ‘em play” is the common refrain.

Umpires are usually ignored by the casual fan. It’s often said that a well-umpired game is one in which you don’t even remember seeing the umpires. “Let ‘em play” is the common refrain.

Indeed, focusing on the umpires would not be an attractive option for most fans. Essentially, you cannot watch the game. You cannot track the ball, the pitcher, the batter, the fielders, or the runners when your full concentration is on the umpires.

Our objective was to better understand and appreciate the active and important role of each umpire. If umpires are the “most neglected, least appreciated, and most misunderstood” participants in the game, then we would choose to focus on the umpires continuously.

Unlike the players, the four umpires remain on the field between turns at bat—they are there, standing on the field continuously, for the entire game, including any extra innings. In the 2009 season the average game lasted just under three hours (2:55:23, to be exact).[fn]Major League Baseball, The 2010 Umpire Media Guide (New York: Major League Baseball, 2010), 77.[/fn] No rest breaks. What do they do all the time? We wanted to find out.

Working the plate is rough. I didn’t like it, but I had to do it to keep my job. It’s the hottest place in the park. You have to call about 250 decisions a day with the sun beating down on the back of your neck and nobody to hand you a sponge and no time in the dugout.[fn]Gerlach, 20.[/fn]

—Beans Reardon, NL Umpire (1926–49)Calling pitches is the toughest job in the game, but I loved it because you’re really in the game back of the plate. On the bases you start day-dreaming when there isn’t much action, and the next thing you know you’re in trouble.[fn]Gerlach, 136.[/fn]

—Joe Paparella, AL Umpire (1946–65)From a crouched position behind home plate, a plate umpire makes between 270 and 300 ball or strike calls per game. The pitches he watches move at 70 to 95 miles per hour. At such speeds, it’s impossible to watch the pitch’s entire movement, so the umpire tracks the pitch as best he can and makes his call on the basis of its after-image—that is, the momentary picture one has of an object after it has completed its trajectory. Like hitting, calling balls and strikes requires a high level of concentration; it also requires good eyesight and being in the best position to see the pitch.[fn]Gmelch, George and J.J. Weiner, In the Ballpark, The Working Lives of Baseball People (Washington, DC and London: The Smithsonian Institution, 1998), 141.[/fn]

The 2009 Squats Leader: (Tim) McClelland compiled 11,417 squats in his 37 plate assignments, including the postseason. He averaged 308.6 squats per game.[fn]Major League Baseball, The 2010 Umpire Media Guide, 93[/fn]

THE ASSIGNMENTS

A team of seven SABR members attended the game on Friday, September 10, 2010, when the San Francisco Giants were in San Diego to play the Padres at Petco Park (7:05 P.M. game start). The Crawford Crew, MLB Crew ‘J’, umpired the game.

Each of the seven SABR members was assigned one umpire to watch throughout the entire game. Thus, we ended with three teams of two members each and one solo assignment:

| Position | Umpire | SABR Members |

| HP | Chris Guccione | Dan Boyle, Andy McCue |

| 1B | Jerry Crawford | Fred O. Rodgers |

| 2B | Phil Cuzzi | Li-An Leonard, Andy Strasberg |

| 3B | Brian O’Nora | David Kinney, Bob Hicks |

The charge for each member was to observe a designated umpire and to maintain an ongoing log—in their own way and style—describing on a continuous basis what the umpire was doing, including his positioning throughout the game and between innings.

On the day following the game, Saturday, September 11, 2010, each of the members was provided an opportunity to discuss with two members of the Crew (Cuzzi and Guccione) any of their observations or issues concerning actions taken by “their umpire” during the game.

Following this meeting each member was asked to prepare a written report of their observations and subsequent discussion with Crew members. The end product, this report, is essentially a compilation of the individual authored reports summarizing the actions of the umpiring crew throughout the game.

It is important to note that the assignment was NOT about evaluating the performance of the umpires.

I conditioned myself like a fighter, so I would never have to leave the field during a ball game. I didn’t drink too much liquid or eat much food before a ball game. If you overdo one or the other either you have to go to the bathroom or you get logy.[fn]Gerlach, 229[/fn].

— Ed Sudol, NL Umpire (1957–77)We always try to help each other. If you see that a guy’s too slow, or you notice something he’s doing that he normally doesn’t do, you tell him so that he can correct it. One of my partners last night said he has been struggling at first base and didn’t know why. The play was just collapsing on him. It was bang, bang—and he was having a hard time reading it. I told him to move further away from the bag: ‘You have to get to where your eyes work best for you. It’s all in the angle and the eyes.’ He moved further away, made a little adjustment, and his problem cleared up. That’s the way it is—you depend upon your partners to help you with that fine tuning.[fn]Gerlach and Weiner, 144.[/fn]

—Durwood Merrill, AL Umpire (1976–99)

MLB UMPIRE CREW ‘J’

Crew J’s four umpires have worked an average of more than 2,250 MLB games, with Crawford leading the group with 4,267 games umpired over a 33-year span. By the end of the 2010 season, he stood at ninth on the all-time list of MLB games umpired.

Here are the four umpires in the Crawford Crew (statistics through 2009[fn]Major League Baseball, The 2010 Umpire Media Guide.[/fn] [fn]http://www.retrosheet.org.[/fn]):

| Uniform No. | Umpire | 1st MLB year | Games | Ejections |

| 2 | Jerry Crawford, Chief | 1976 | 4,267 | 79 |

| 7 | Brian O’Nora | 1992 | 1,934 | 27 |

| 10 | Phil Cuzzi | 1991 | 1,456 | 57 |

| 68 | Chris Guccione | 2000 | 1,390 | 44 |

Jerry Crawford was born in August 1947 in Philadelphia and resides in Florida. His father, Henry “Shag” Crawford, was a National League umpire from 1956–75 and his brother, Joe, is a referee in the National Basketball Association. Crawford attended umpire school in 1967 and worked his way up through the minor leagues until joining the Major League staff in 1977. At 33 years he has the longest tenure of any present umpire and is four years shy of the record of 37 years set by Bruce Froemming and Bill Klem. He has umpired 108 postseason games, second only to Froemming. Over the course of his career he has averaged 1.85 ejections per 100 games.

Brian O’Nora was born in February 1963 in Youngstown and still lives in Ohio. He is a graduate of the Joe Brinkman Umpire School in 1985. His ejection rate has been 1.40.

Phil Cuzzi was born in August 1955 in New Jersey, where he still resides. He umpired his first major league game in 1991, and joined the MLB staff full-time in 1999. Cuzzi was the home plate umpire for Bud Smith’s no-hitter on September 3, 2001. His ejection rate has been 3.91.

Chris Guccione, who resides in Colorado, was born in June 1974 in Salida, Colorado. He has 14 years of professional baseball umpiring experience. His ejection rate has been 3.17.

My theory for the general lack of curiosity about umpires is that fans tend to find all the anomalies distancing rather than appealing. They make umpiring too peculiar, too enigmatic, too difficult to analyze. It’s not that umpires are hidden exactly, or even inconsequential. Rather, it’s as if, both on the field and off, they inhabit a parallel world to that of the rest of baseball. If you watch a game the way you normally do, focusing on the ball and the players throwing it, hitting it, or chasing it, the umpires will seem to be absent—it’s a little weird, actually; you just don’t see them, even though they’re often right in the middle of the action. The next time a catcher goes back to the screen for a foul pop, for example, take a moment to look for the plate umpire. You’ll find him surprisingly nearby, just a few feet from the catcher, peering intently at the ball as it descends, to make sure it doesn’t graze the screen before it hits the catcher’s glove.[fn]Weber, Bruce, As They See ‘em, A Fan’s Travels in the Land of Umpires (New York: Scribner, 2009), 30.[/fn]

NOTES ON OFFICIAL BASEBALL RULES

By Bob Hicks

On the evening of Friday, September 10, 2010, the San Francisco Giants defeated the San Diego Padres at Petco Park 1–0 in front of more than 30,000 fans. The two teams combined for just ten hits. Each team collected only one extra-base hit each—a double. Neither extra-base hit factored in the scoring. As in virtually every Major League Baseball game, this contest was officiated by a team of four umpires responsible for ensuring the game is played under the Official Baseball Rules of Major League Baseball.[fn]Major League Baseball, Official Rules of Major League Baseball (New York: Major League Baseball, 2010).[/fn]

All in all, the lack of offense may lead the casual observer to conclude that the ball game was fairly easy to officiate. “Not so,” stated two of the umpires who were asked that question the following day over breakfast. The game pitted the two top teams in the National League Western Division, magnifying the importance of each play. The fact that the game was so close meant that every call was critical.

The game included several close calls, including a few line drives down the third-base line, a couple of “bang-bang” plays at third, a critical caught stealing at second, a few close plays at first base (the sole run scored on a 5–4 fielder’s choice which just missed being a 5–4–3 inning-ending double play), and, finally, an unusual ninth-inning call at home plate which killed a bases-loaded rally—a call that neither umpire interviewed had ever invoked during their combined 30+ years of professional umpiring. Yet that rule had to be recalled and confidently conveyed to the players and the crowd in a matter of a second or two. Not an easy day at the office.

Even the most casual baseball fan is aware of an umpire’s responsibility to understand and immediately apply the Official Baseball Rules to the games they work. The Official Baseball Rules, a 129-page document published by the Office of the Commissioner, is divided into 10 sections. Nine of those sections—87 pages—describe rules directly relating to the umpire and the conduct of the game, the equipment, and the field on which the game is played.

Contained within those sections are the obvious and the obscure. Every application of those rules must be accurately and confidently recalled within a second or two in the heat of the action under the watchful eyes of the 50 or so uniformed combatants, the press and broadcast personnel, 30,000+ fans in the stands, the MLB umpire evaluation staff, thousands watching live on TV or the web, and thousands more who will acquire an account of the game via newspaper, newscast, MLB.com, or various other means available to the millions of baseball fans throughout the United States and abroad.

The Official Baseball Rules have undergone more than 45 revisions from the time they were revised and codified in 1949. The two leagues have slightly different rules, most of the differences surrounding the designated hitter. Each ballpark has different ground rules, grounds crews, official scorekeepers, ball boys and girls, public address announcers, and audio/video staff with whom the umpires may interact.

Although the average baseball fan is aware of the Official Baseball Rules (which are available to the public at MLB.com), the umpires must fully comprehend and execute another book: the MLB Umpire Manual,[fn]Major League Baseball, MLB Umpire Manual (New York: Major League Baseball, 2010).[/fn] published by the Office of the Commissioner of Baseball and not available to the public. Over 150 pages it details desired “Conduct & Responsibilities,” “Procedures and Interpretation,” and “Mechanics for the Four-Umpire System,” covering virtually every potential game situation and the “Umpire Evaluation and Training” system.

In my view, the most interesting section of the MLB Umpire Manual is the “Mechanics” section. Within those 40-plus pages are dozens of combinations of umpire movement and responsibilities depending upon what runners are on which base and the number of outs. Perhaps most impressively, MLB outlines the responsibilities of each umpire (unless field conditions require temporary alterations), but the positioning executed to meet those responsibilities varies somewhat depending upon the desires of the crew chief and his arbiters. Positioning and other such issues are negotiated and decided upon before a crew works together for the first time. To me this is another example of the high level of knowledge and teamwork MLB requires of its umpiring crews.

Consider that a crew is occasionally altered by a substitute umpire filling in due to illness or vacation. Even more challenging is a last-minute illness or game injury which may leave the four-man crew short one member. When taking these situations into account, these positioning variations—which may uniquely distinguish each crew—add another degree of difficulty to umpiring. Many of us never considered this interesting subtlety of the game before undertaking this project.

UMPIRE OBSERVATIONS AT HOME PLATE

By Dan Boyle with Andy McCue

Prior to the September 10 game, Dan practiced watching umpires for an inning or two and found it to be much harder than he had guessed; after many years of watching baseball, the first instinct is to follow the ball after the crack of the bat. These preliminary observations revealed certain patterns that each umpire has, and these patterns or rhythms are virtually identical with every pitch.

For this evening, the two of us watched home plate umpire Chris Guccione. He has been a full-time major league umpire since the start of the 2009 season and umpired his first MLB game in 2000. One of us watched the umpire closely for the top half of an inning, while the other described where each batted ball was going so that the watcher would have a sense of what the umpire was reacting to. Every half inning, we switched roles. We also kept track of the number of decisions made by the home plate umpire throughout the course of the game. (Swinging strikes, foul balls, balls in play, and intentional walks did not count.) Our guess prior to the game was that Guccione would have to make 200 decisions during the course of the day. The final total is at the end of this section.

We recorded our observations by inning and noted our questions, since we knew that Chris would be at breakfast the next day.

- First Inning. Prior to the game we thought of (and promptly forgot) two great questions: how did Chris develop his style of calling strikes and how does he time a visit to the mound? We noted that he hustled three-quarters of the way down the first-base line on a popup that could be fair or foul, since the first-base umpire has to make the fair-foul call and also call any play at first base.

- Second Inning. We had become acclimated to Chris’s rhythm by this point. He stands well behind the catcher then moves up and crouches as the pitcher is in his windup. He sets up to look over the inside corner with his outside hand resting on the catcher. This movement was consistent throughout the game. In this inning, he threw a new ball to the pitcher after a foul; in later innings, he handed the new ball to the catcher. We noticed him nod toward the San Diego dugout during this inning for no obvious reason. After the third out, he threw a new ball to the mound prior to the next inning. Between innings, he took new balls from the ball boy and stood halfway down the first-base line watching the pitcher throw his warm-ups.

- Third Inning. Padres first baseman Adrian Gonzalez made a between-the-legs catch on a bounced throw from third base after the ball had been called foul. Guccione came out to the mound and said something to pitcher Clayton Richard. Afterwards, we realized that he was taking the ball, which had bounced in the dirt, out of play. Upon closer inspection, we found a slight variation in Chris’s stance: for left-handed batters, his feet are even, but for right-handed batters, his left foot is slightly closer to the catcher than his right. Before the last warm-up pitch between innings, he signals with his right hand to the batter, waiting on deck, to move up to the plate.

- Fourth Inning. Another thought we had but forgot to ask him about: how many balls are in his ball bag at any one time? The between-inning routine was different this inning. Chris had a long conversation with someone in the Padres dugout. We assumed it must be a coach, but the conversation partner turned out to be Yorvit Torrealba. We also noticed that he disallowed Jonathan Sanchez’ first pitch on an intentional walk, making it a rare five-pitch IW.

- Fifth Inning. Chris called time and took a ball out of play after it had bounced in the dirt. This was when we realized the answer to the question back in the third inning about the visit to the mound. With a man on first base, Chris goes all the way down the line to the first-base bag on a fly ball to right field. In the same situation, he goes halfway down the third-base line on a fly ball to left-center. Chris holds his ball-strike indicator in his left hand, but only looks at it between at-bats or with a full count. Our guess is that he is re-setting it.

- Sixth Inning. Chris motioned to the press box when a pinch-hitter entered the game. He picked up a bat down the first-base line for the batboy. He went out to the mound to check the ball after a throw to first had bounced in the dirt. Somewhere around this time, we realized that we had no idea of what was going on in the game. Giants pitcher Sanchez came out after issuing seven walks; this was news to us. Is Buster Posey in the lineup tonight? Who’s coming up next inning? What inning is it, precisely? We had no clue. The one watching closely often had to ask what happened on a particular play; every now and then, we’d look up briefly and find men on base when we didn’t expect to. Of course, this only meant that we were doing our job, but it was still disconcerting.

- Seventh Inning. What proved to be the only run of the game scored on an attempted double play. Chris kicked the bat out of the way and stood just behind the plate when it was obvious that there would be no play at home. With a man on first, he came down the line only a little bit on a blooper to right field. We surmised that if the ball had taken a funny hop, there could have been a play at home.

- Eighth Inning. Chris gave some extra time to Padres catcher Nick Hundley, who had been hit by a foul ball. Chris walked out in front of home and kicked dirt off the plate. One of us asks the other, “Has he dusted off the plate yet tonight?” We remember seeing him kick dirt off the plate just as he had here, but neither of us recalled seeing him use the brush. Maybe he forgot it tonight? Chris had a discussion with the San Diego dugout before the visitor eighth, apparently regarding a new Padres pitcher. With a man on first, he trotted down the third-base line on a single to left. He chatted with Aubrey Huff at the plate while Hundley visited the mound (this happens twice during the at-bat). It’s the only time we observed him talking to a hitter or catcher, although the mask made it difficult to tell. He chatted with the ball boy between innings.

- Ninth Inning. With one out and the bases loaded in the top of the ninth, Giants pitcher Brian Wilson hit a comebacker to the mound. Ryan Webb threw to the plate to force Jose Uribe, but catcher Hundley did not throw to first. After a second, Guccione signaled that Uribe had interfered with Hundley and ruled it a double play. Giants’ manager Bruce Bochy came storming out of the dugout but retreated after about five seconds of conversation. Replays clearly showed that as Uribe slid into home, he reached out and grabbed Hundley’s ankle. Chris was positioned slightly to the third-base side of home plate.

HOW MANY DECISIONS?

(Measuring pitches that the umpire needed to “rule” on, meaning swinging strikes and fouls were not included)

- Inning 1: 22 (16 balls, 6 called strikes)

- Inning 2: 26 (15 balls, 11 called strikes)

- Inning 3: 12 (9 balls, 3 called strikes)

- Inning 4: 11 (6 balls, 5 called strikes, intentional walk not counted as a decision)

- Inning 5: 20 (17 balls, 2 called strikes, one fair/foul on a foul ball off the batter’s foot)

- Inning 6: 13 (10 balls, 3 called strikes)

- Inning 7: 17 (12 balls, 4 called strikes, one checked swing)

- Inning 8: 10 (7 balls, 3 called strikes)

- Inning 9: 19 (12 balls, 5 called strikes, one checked swing, one interference call)

Total: 150 decisions (in our inexperience, we may have missed some pitches)

UMPIRE OBSERVATIONS AT FIRST BASE

By Fred O. Rodgers

Ozzie Guillen, the current manager of the Chicago White Sox, once stated that nobody comes to the park just to watch an umpire work. That is no longer true. I watched one umpire for the entire game.

The game lasted 3:03 with the only run scoring on a fielder’s choice. There were 289 pitches thrown and 72 batters made plate appearances.

I covered Jerry Crawford, the first-base umpire, who is also the crew chief. This is Jerry’s 34th year as a major league umpire and would be his last (he retired following the 2010 postseason). Interestingly, both Jerry and his father, Shag Crawford, spent over ten years of their careers working on the same crew as recently inducted Hall of Fame umpire Doug Harvey.

During the course of the nine innings that Jerry covered first base,

- 39 batters (54%) came up with no one on base;

- 18 batters came up (25%) with a runner on first;

- 4 batters (6%) hit with a runner on second;

- 9 batters (13%) appeared with runners on first and second;

- One batter came up (1.4%) with runners on first and third; and

- One batter appeared (1.4%) when the bases were loaded.

So what did Jerry Crawford do with nobody on base?

Jerry began each pitch standing approximately 15–20 feet behind the first-base bag and just outside the foul line. This was meant to increase the chances that if he was hit with a batted ball, it would be foul. Jerry would start moving in about four or five paces as the pitcher started his windup. As the pitcher planted his foot Jerry would freeze and either keep his hands on his knees or be at the ready with his hands by his side. He would do this on virtually every pitch.

You could see how focused and how intently Jerry would watch each pitch; he knew he might have to help the home plate umpire on checked swings, balls in the dirt, foul balls hit off the batter, and foul tips on third strikes. There is no relaxing during a pitch.

In two instances, Jerry had to call a ball down the right-field line “fair” or “foul.” He also ran into the outfield on three occasions on fly balls hit to right field and right-center.

With runners on first base, Jerry would situate himself about ten feet from the bag with a perfect angle to watch the pitcher for a balk or a pickoff throw to first. During the game a pitcher threw over to first seven times. Only once did Jerry have to make a tough call on a pickoff attempt.

The closer the call, the more need to “sell” the call so that the crowd understands you are in charge and that you saw it correctly. A little bit of confidence and showmanship is needed to make sure that everyone in the park understands a delicate call.

Jerry would move approximately ten feet toward second base and about five feet behind the first baseman once a ball was hit to the infield. This is considered the best position to be in to see the first-base bag and to listen for the ball in the mitt to make a decisive call. Jerry had to “sell” two tough plays. The only run in the game scored when Jerry called the batter safe running to first on the backside of an attempted double play. There was no argument.

Because the teams combined for only two extra-base hits, umpire rotation was at a minimum. Only twice did Jerry have to run toward second base in case he would need to make a call. Neither time was a play made.

Between innings Jerry seldom moved from the area directly behind first base where the grass and the dirt meet. Never once did he excuse himself from the field. In the sixth inning, Jerry ambled over to the first-base seats just past the dugout and shook hands with ex-Padres ballplayer Kurt Bevacqua, who introduced Jerry to his wife and two kids. Then Jerry actually signed a ball for Kurt, which I’m sure is not a normal occurrence during a game.

Most of the time between innings, Jerry showed amusement at what the Padres showed on the scoreboard, be it the Kiss-Cam or baseball bloopers. I could also tell that Jerry was entertained when the grounds crew (one of whom put on a dance routine) raked the infield between innings.

I found it amazing that a 1–0 game could go over three hours. The very next night, another 1–0 game lasted only 2:07.

My observation of Jerry Crawford working first base for the whole game made me more aware of all the work umpires do just to prepare to make a call that may not even come their way. The stress from pitch to pitch is huge. Working the bases can be just as demanding as working home plate.

I think I would rather sit up in the stands and watch the players—and I guess now, the umpires—entertain me.

UMPIRE OBSERVATIONS AT SECOND BASE

By Li-An Leonard and Andy Strasberg

Regardless of the number of baseball games you have seen, you are probably missing a vital aspect of the game that has eluded fans, broadcasters and the baseball media since the first pitch was called by an umpire some 150 years ago.

Realistically, few, if any, attend a baseball game for the express purpose of following one umpire for an entire game. No one charts an umpire’s every move on every pitch and batted ball. And certainly no one makes notes of what an umpire does between innings. But if you did, you would see a baseball game from the inside-out and upside-down guaranteed.

We followed and detailed every move of the second-base umpire, Phil Cuzzi, during this game. We were provided unprecedented access to the umpire after the game and were able to find out the reason for each movement or gesture. We were also informed of casual conversations or argumentative conversations by the umpire himself. It was a revelation; the explanations were interesting, intriguing, and revealing.

Our observations took place in a three-hour, three-minute game during which the second-base umpire was constantly on his feet in a “get ready” position every time a pitch was thrown, hustling into position, then hustling back. He didn’t take a bathroom break nor did he get anything to drink while working the game.

Other observations (some involving all umpires):

- Each umpire taps the chest protector of the plate umpire after the conclusion of the pregame meeting between the two teams where clubs exchange lineup cards.

- On double plays beginning at second base and involving a relay throw, the second-base umpire sees only the play at second base. He does not watch a throw after it leaves the middle infielder’s hand.

- When a runner is on base, the second-base umpire watches the pitcher for the possibility of a balk.

- On balls hit to the outfield, the second-base umpire does not run toward the ball butrather slightly away from it for the express

purpose of getting a better angle to see whether a catch is made. - When a pitcher throws to first base, the second-base umpire appears to relax and back up on his heels. In reality he is expanding his vision, anticipating the possibility of a play at second base.

- After the third out of each inning, the second-base umpire removes a stop watch from his pants pocket and begins monitoring the two minutes and five seconds needed for the commercial break to ensure that the game does not resume before the TV/radio audience returns.

- The second-base umpire looks for every player to touch second base when traveling the bases.

- Every umpire must wear the gear necessary for the weather conditions and the position he works.

- A demonstrative up-and-down hand-clap before the next batter signifies to the other umpires the possibility of the infield fly rule taking effect. (The signal for the infield fly rule may vary from umpire to umpire or from crew to crew.)

- The rotation to cover the bases by the umpires is not an exact science, but rather the closest thing one may ever see to teamwork.

- Anticipating the possibilities is an ongoing process for every umpire for every play imaginable.

- An umpire’s physical condition could impact how a crew works a game. There is always the possibility that one of the four umpires might not be able to complete the game, and as a result, the umpires must be prepared to adjust their approach to the game.

- Discussing the play with a player or manager is part of the game, but generally only happens in case of a disagreement. Many times this takes place with elevated emotions and voices.

- Looking for the best angle is the quest of every umpire on every play. Positioning is the key to a good angle.

- Every move and possible play is not only anticipated but must also be instantaneously applied to the official rules of the game.

- Most media members covering a game have little knowledge of the rules of the game and often base their opinions and criticisms of umpires on misinformation or lack of knowledge of a rule.

THE CHALLENGES

- Loneliness. An umpiring crew consists of four men. The

support team of an umpire crew is limited to only the

other three men. - Travel. After spending a series of games in one city, the crew must travel to another city to work the games of two new teams. It is MLB policy that the umpire crew not continue to work the same two clubs.

- Stressful conditions. Instant recall of applicable knowledge of the rules in front of thousands or millions of people must occur within seconds of a play. When an umpire is working, situations that happen infrequently require umpires to recall the applicable rule immediately and perfectly.

At the end of the day, who appreciates the work of an umpire? There is no home team. They have no fan club, and the MLB office doesn’t appreciate the intricacies of their work, essentially because the MLB office has never experienced it. As the adage says, “The only time an umpire is noticed is when something goes wrong”—or, in most cases, “appears” to go wrong. Yet umpires are dedicated and proud of the work they do. MLB umpires are the best baseball fans the game has. They don’t root for a team or a player, but they love the game as much if not more than any die-hard fan.

UMPIRE OBSERVATIONS AT THIRD BASE

By David Kinney and Bob Hicks

GENERAL OBSERVATIONS

Prior to a pitch, third base umpire Brian O’Nora takes a preliminary position at the point where the infield dirt meets the outfield grass. As the pitcher looks in for the sign from the catcher, O’Nora moves a couple of steps toward third base, straddling the third-base/left-field chalk line with one foot in fair territory and one in foul. Like the infielders, as the pitch is thrown he takes a set position. Usually this set is a modified scissors position with left leg forward. He repeats this motion with every pitch. Brian does not vary his starting point based on right- or left-handed batter, power hitter, or potential bunting situation. He is achingly consistent with this pattern.

With a left-handed batter, he would not follow the pitch to the plate but instead would focus on the batter to be prepared for a check swing. With a runner on base, the umpire would observe the pitcher until he was past the possible balk point and without following the pitch immediately turn his glance to the batter to observe a possible check swing. Also, when a runner occupied second base, immediately after the set O’Nora would cast a quick glance at the runner, much like a third basemen would, presumably to gauge the runner’s lead and possible intent to steal. When an action was unlikely to produce a play at third base (either a ground ball or fly ball to an area of the diamond other than near third base, and with no runners on base) the umpire would basically remain in position but turn and follow the play.

With runners on base, his focus was always on any possible action at third base. For example, with a runner on base and an infield ground ball, O’Nora would not watch the resulting play at first base but would be in position to observe the runner touching third.

With fly balls to left field, the umpire had the responsibility to observe the catch, determine fair or foul, and observe any action at third base. Sometimes he was required to do all three on one play. On a foul pop-up toward the far end of the third-base dugout, O’Nora appeared to gauge where he thought the ball and defender would end up. He ensured that he didn’t interfere with the defender’s path to the ball, but immediately after that danger was averted, sprinted to a position where he could see the open glove as the fielder caught the ball. This cone of vision, in which every umpire tries to center each play, provides the best angle for a catch, tag, drop, or trap. It appeared that O’Nora attempted to be at a standstill before the catch was made.

Between the top and bottom of the third inning O’Nora drank from a water bottle offered by the Padres’ ball girl.

Between some innings, the grounds crew quickly drags the infield, rakes around the base areas, replaces the bases, etc. Often the Padres send out a dancer dressed as a member of the grounds crew to perform for the crowd in shallow center field just beyond second base. His routine usually generates a good response from the crowd and, on the rarest occasion, a simple acknowledgement from the third-base umpire as the dancer exits the field. O’Nora’s body language seemed to communicate to the dancer that no acknowledgement would be forthcoming. “No harm, no foul,” but no high-five either.

O’Nora never sat down and never left the field until the game was over. At the conclusion of the game the umpires gathered together between home and third base and left the field as one.

He often watched the promotions on the video screen between innings, albeit never in their entirety. It appeared that recent baseball highlights held none of O’Nora’s interest. He did, however, glance at the screen for a blooper segment or two.

Between innings, early in the game, O’Nora talked briefly with Padres third-base coach Glenn Hoffman and with Giants third-base coach Tim Flannery.

He spoke, very briefly, with Giants left fielder Pat Burrell before the bottom of the first as the latter was walking to his position from the Giants dugout on the third-base side.

SPECIFIC OBSERVATIONS

On a number of plays, the umpire had to move in various directions on the field:

- Easily played fly ball to outfield. Umpire moved five or six feet toward the shortstop position.

- High foul fly toward right field. Umpire moved ten feet on infield grass near shortstop position.

- Deep drive to center. As the second-base umpire went out to observe the catch, the third-base umpire moved toward second anticipating a play.

- Ground ball down the third base line. Umpire moved several feet into foul territory to observe whether the ball was fair or foul.

- Deep drive to right field with runners on first and third. Umpire moved closer to third to observe the touch of the two baserunners. He did not observe the flight of the ball or the catch.

- Long foul ball to left field. Umpire went out to observe the catch.

- Pop up to pitcher. Umpire moved toward the pitcher’s mound to observe the catch.

- Fly ball to left field. Umpire went out to observe the catch and raced back to third anticipating a play.

- Ground ball to short with runners on first and second. Umpire moved to a position near third in foul territory.

- Foul pop-up near third base stands. Umpire waited for the fielder to take his route, moved in toward the infield several feet, and raced toward the stands to observe the catch. (See comments above.)

- Fly ball to left field runners on first and second. Umpire went out to observe catch.

BREAKFAST MEETING THE DAY AFTER

By Dan Boyle

On our reaction. At breakfast the next day, Phil Cuzzi first asked us if this project had affected our views of umpires. We said, “Yes, absolutely.” Even in a low-scoring game, without much action on the bases, much happened that we would have never otherwise observed.

On our reaction. At breakfast the next day, Phil Cuzzi first asked us if this project had affected our views of umpires. We said, “Yes, absolutely.” Even in a low-scoring game, without much action on the bases, much happened that we would have never otherwise observed.

General comments on positioning. Chris described the flight of the ball and the path of the runner as forming a V on plays at the plate, and the umpire wants to be at the intersection of the two lines. Home plate umpires typically are slightly up the first-base line in foul ground because throws to the plate are usually caught in front of the plate. The idea is to have a clear line of sight between the runner and the catcher (the runner’s side of the V) to determine whether the tag is made. The diagram shown earlier for the interference play at the plate indicated that Guccione was slightly to the left of and behind home plate, which seems to contradict the idea of being at the intersection of the V. On that play, however, the bases were loaded and the home plate umpire was looking at a force, not a tag play. Chris was in the best position to see whether the runner beat the throw.

On our observation that this seemed to be an easy game to call. A tight game like this is never easy, especially in a pennant race. Any one call could change the game, unlike in an 8–0 game.

The stopwatch. As the second base umpire, Phil had the stopwatch to monitor the time between innings. In response to a question, he said that everything ran smoothly.

On whether he needs to unwind after a game, particularly when working the plate. Chris said he always falls asleep quickly once he’s back in the hotel.

Why his left foot is closer to the catcher than his right foot for right-handed batters. Chris said that he does move in a little closer for righties. It seems that he could not move closer for lefties because of the possibility of interfering with the catcher’s throw. Phil was surprised by the answer; he never noticed Chris doing this.

The conversation with Torrealba. Chris knows Torrealba from when they were both in the California League (as umpire and player). In the game the night before, after a controversial call at first base, the television cameras picked up some back-and-forth between Adrian Gonzalez and Guccione. Torrealba was telling Chris that Adrian had asked him if Guccione always goes back at you, and Torrealba responded, “Nah, only if you piss him off.”

The five-pitch intentional walk. Someone called time before the first pitch for reasons unknown.

Brushing off home. Guccione had the brush (he said, while patting his shirt pocket) but had no reason to use it in a 1–0 game.

The interference call. Chris noted that he did not call interference immediately. During the delay of perhaps a second, his brain ran through everything he was seeing, and he decided that it clearly was interference. Especially interesting is that this was the first time in his career that Guccione had called interference on a

play at the plate. Bochy assumed that the interference call was because the runner was out of the baseline (the typical interference call on the bases) and wanted to show the path of Uribe’s slide to Guccione, but Chris quickly told the manager that he called interference because Uribe hooked the catcher’s ankle with his hand. Once Bochy heard that, the argument ended.

In response to a question, Chris said that whether Hundley had a play on the man at first had no bearing on the interference call. It was not the home plate umpire’s job to determine whether the runner might have been out at first without the interference, primarily because there was no way to make that determination. Jerry Crawford, the first-base umpire, told Guccione after the game that the batter was running far inside (i.e., on the fair side) of the baseline. A throw might have hit the runner in fair territory.

CONCLUSION

By Andy Strasberg

“People only know to hate us. We are a misunderstood group. People don’t really know us, but to know us is to love us.”

— Phil Cuzzi

Our Saturday morning get-together with Cuzzi and Chris Guccione provided the perfect opportunity to ask questions about the game they had umpired the previous evening at PETCO Park. Our questions ranged from what was said during the game to players in between innings, to the umpires’ hand signals for a potential infield fly rule possibility, and a catcher’s interference call. The umpires appeared candid and forthright with their responses.

It became evident as they responded that the umpires love their job, take an enormous amount of pride in their profession, and are extremely knowledgeable of baseball in general, not only the rules.

They were generous in sharing insights about what goes on during a game for those men standing on a baseball diamond who are not players, coaches, or managers. Our conversation was speckled with humor and revelations.

As a result of the questions we asked and the answers we received, our conclusion was that an umpire’s approach to the game is a combination (in no particular order) of sociability, knowledge of the rules, ability to make split-second decisions, and at times—when it is needed—to control the game so that is played fairly for both teams.

While the fans watch the pitcher and batter get ready for a pitch, each umpire is preparing for the play and constantly aware of his (so far, his) field conditions and player positioning, ready to anticipate any number of rule possibilities depending on game situations. For instance, we discussed a play from the previous night’s game in which Giants closer Brian Wilson hit a comebacker to the mound and runner Juan Uribe interfered with catcher Nick Hundley. This was not a play that could have easily been anticipated, but yet was called in less time that it took to write this sentence. We asked Chris how many times he had called that play and were surprised to hear him respond, “That was the first time I ever made that call.”

That play, and that call, indicate how an umpire must be decisive, have an instant and accurate recall of rules, and remain continuously observant. The umps may appear to be enjoying the game in a casual manner, but they are working the entire time the game is being played.

As we departed our meeting with Guccione and Cuzzi, we realized that we had a better understanding of what it was to be an MLB umpire. We learned about their challenges and found them to be personable and—clichés be hanged—even likeable.