Oscar Charleston No. 1 Star of 1921 Negro League

This article was written by Dick Clark - John Holway

This article was published in 1985 Baseball Research Journal

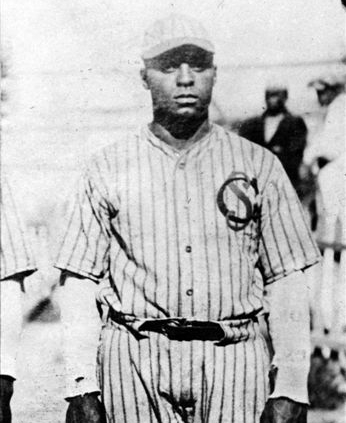

Oscar Charleston was known as “the Black Ty Cobb.” Both men sprayed line drives to all fields and played a savage running game on the bases. But Charleston hit with power, which Cobb did not, and on the field he ran circles around the more famous Georgian. He was considered in a class with Tris Speaker in center field.

Oscar Charleston was known as “the Black Ty Cobb.” Both men sprayed line drives to all fields and played a savage running game on the bases. But Charleston hit with power, which Cobb did not, and on the field he ran circles around the more famous Georgian. He was considered in a class with Tris Speaker in center field.

By common agreement among Black old-timers, Charleston was the greatest all-around player in the annals of the Negro Leagues. His modern counterpart would be Willie Mays, who played with a similar panache.

In 1921, Charleston had a year that not even Cobb, the Georgia Peach, could match. Oscar hit .434 in 60 games against the top Black teams and led the Negro National League (NNL) in batting, home runs, triples, and stolen bases.

These figures are the result of hundreds of hours of research by dedicated SABR members and others who pored over miles of microfilm of both Black and White newspapers in seven cities. It is part of an ongoing project to compile the most complete statistics possible for the Negro National League for the 1920–1929 period. Future projects will seek to cover the Eastern Colored League for the same decade, then move on to the Negro League data for the 1930s and 1940s. We feel confident that we have found every box score that still exists for the year 1921, although unfortunately many were apparently not published and presumably will never be found.

As compiled by project editor Dick Clark, here are the highlights of that year:

It was the second season of the new league, which was founded in the winter of 1919-20 by Rube Foster of the Chicago American Giants, J.L. Wilkinson of the Kansas City Monarchs, and owners of other midwestern Black clubs. Foster’s American Giants won the first pennant in 1920 with ease.

As the clubs took spring training for the new season, one key sale was announced. The Indianapolis ABC’s (named for the American Brewing Company, which owned them) sold their star outfielder, Charleston, to the St. Louis Giants. Charleston started fast for his new club, smashing two home runs and four singles in one game against the Chicago Giants (not the American Giants).

His feat was almost matched in the same game by Giants’ rookie John Beckwith, who hit a home run, triple, and two singles in five at-bats. Beckwith, a moody man but a formidable slugger, would go on to become one of the four or five top home-run hitters of Negro League history. His name would be mentioned along with those of Josh Gibson, Mule Suttles, Turkey Stearnes, and Willard Brown.

Nine days after his duel with Charleston, Beckwith arrived in Cincinnati’s Redland Field for a game against the Cuban Stars. Beck smashed a drive over the left field wall just a few feet from the large clock. It was the first ball ever hit over the new barrier. Fans showered the promising youngster with coins and dollar bills as he crossed home plate.

St. Louis hitters terrorized the league that year largely because of the strange dimensions of the club’s home field, which was built beside the trolley car barn. The barn cut across left field, leaving a short fence at the foul line. The fence quickly dropped back to a deep center field. Righthanded hitters had a great time aiming at the barn. Although Charleston was a lefty, he hit to all fields, and there is no way of knowing how much the short left-field fence helped him.

Foster’s American Giants moved to the head of the league again, using Rube’s unusual style of bunt-and-run offense combined with the finest pitching in the league. They finished last in league batting, with only one legitimate slugger, the Cuban Cristobal Torriente, who hit .330 that year and is usually included on most authorities’ all-time all-Black team along with Charleston. Bingo DeMoss, perhaps the best Black second baseman ever; Dave Malarcher, Jimmy Lyons, and Jelly Gardner represented the Rube Foster style, getting on base any way they could, bunting, hitting, and running, and waiting for Torriente to knock them in. Lyons was a veteran of Rube’s earlier Chicago Leland Giants. He had served in the U.S. Army in France in World War I, playing against Ty Cobb’ brother. In July Lyons fell 25 feet down an elevator shaft, but he was back on the field four days later. The accident didn’t affect his hitting; he ended up batting .388 for the year.

Besides their speed, the American Giants were first in pitching effectiveness. Tom Williams had a record of 10-5. Dave Brown, the ex-convict whom some consider the best Black lefty of all time, compiled a 10-3 record. One of his victories was a one-hitter against the hard-hitting Monarchs. (Brown would later kill a man in a barroom fight, flee to the West and drop out of sight forever.)

Foster, one of the shrewdest men ever to direct a baseball team, gave signals from the bench with his meerschaum pipe and used his team’s speed and pitching to outplay the hard-hitting clubs. Yet oddly, in spite of their reputation, the American Giants stole few bases if the box scores are to be believed. Chicago relied on speed, but apparently Foster capitalized on it by taking the extra base on batted balls.

For example, in a game against Indianapolis in June the Giants were down, 18-0, so Foster threw away all the books. He ordered his “rabbits” to lay down 11 bunts, including six squeeze plays in a row. Torriente blasted a grand-slam and catcher George Dixon hit another as the Giants scored nine runs in the eighth and nine more in the ninth to gain an 18-18 tie!

League teams played six games a week Saturday through Wednesday, including Sunday and holiday doubleheaders, from May through August. Some clubs played more games than others. The Chicago Giants, the weakest club in the league, played only 38 league contests, according to our count (which differs somewhat from the officially published standings), and spent most of their time barnstorming against White semipro teams. By contrast, the Kansas City Monarchs played 77 league games.

As the July heat descended on the Midwest, the American Giants clung to a slim lead over the hard-hitting Monarchs. Kansas City was led by pitcher Bullet Joe Rogan, the little ex-soldier who had been discovered by Casey Stengel while playing on a Black infantry team in Arizona two years earlier. Little Joe was already more than 30 years old but still one of the all-time stars of blackball history. Most Monarch veterans who saw him insist he was a better pitcher than Satchel Paige, the man who succeeded him as ace of the Monarch staff. Rogan posted a 14-7 record in 1921 and completed all 20 games he started.

Rogan was also a great hitter, though his average that year was only .266. He showed his power in one game, blasting a home run, triple and double in four at-bats against the Cubans.

There was only one no-hitter that summer. It was turned in by Big Bill Gatewood of third-place St. Louis. Six years later Bill would manage the Birmingham Black Barons when a skinny rookie named Satchel Paige joined the club. Satch credited Gatewood with teaching him the “hesitation pitch,” which became one of Paige’s best-known trademarks.

Another St. Louis hurler that year, Bill “Plunk” Drake, always claimed that Satch had learned the “hesitation pitch” from him. Drake had a magnificent season in 1921. St. Louis finished with 40 victories, and Drake was credited with 18 of them to lead the league. That is equal to at least 30 wins in the major leagues’ present 162-game schedule.

The Detroit Stars finished fourth, led by outfielder-manager Pete Hill and catcher Bruce Petway. Hill was a veteran of the great Philadelphia Giants team of 1906, which also boasted Foster, Charlie “Chief Tokahoma” Grant, who had tried to join John McGraw’s Baltimore Orioles in 1902 as an Indian, and young John Henry Lloyd. The Giants challenged the winner of the 1906 Cubs-White Sox World Series to a series to determine the championship of the United States. The challenge was never accepted.

Though few persons are still living who personally saw Hill play and none who saw him in his prime, many who did see him put him on their all-time all-Black outfield alongside Charleston and Torriente. In 1921, Hill could still hit; his .373 average was one of the best in the league. Petway was considered one of the two best Black catchers of all time by those who saw him play. In November 1910, he faced Cobb in Havana an threw Ty out on attempted steals three straight times. On the third try, Ty saw that the throw had him beat and merely turned and ran back into the dugout. Petway, usually a banjo hitter, also out-hit Ty, .412 to .369, and Cobb stomped off the field vowing never to play against Blacks again

Unfortunately, injuries to Hill and to slugging first baseman Edgar Wesley hurt the Detroiters and they failed to mount a challenge for the pennant.

The ABCs, who had sold their top player, Charleston, finished fifth, although they had a great future star in catcher Raleigh “Biz” Mackey, up from Texas. The switch-hitting Mackey hit .289 that year and his seven home runs were third highest in the league. He would develop eventually into the man considered—at least by all who didn’t see Petway—as the best catcher in Black baseball annals. Later Josh Gibson outhit him, but Black vets would have put Josh in the outfield in order to have Mackey behind the plate. After Mackey moved to Philadelphia, he was often compared to Mickey Cochrane.

In 1938, Mackey took a youngster named Roy Campanella and taught him all of his secrets. Later, Charleston urged Branch Rickey to sign Campy to a Brooklyn Dodger contract. The ABC first baseman was Ben Taylor, and again a generational debate rages as to whether he or his latter-day pupil, Buck Leonard, was the finest Black first baseman of all time. Taylor’s 1921 batting average, .415, was third best in the league.

On August 21, Indianapolis pitching ace Harry Kenyon hooked up in a 17-inning duel with Jose LeBlanc of the Cubans. Both went the distance and Kenyon won, 6-5.

The Cubans finished sixth in the league. As usual they had some fine players but were handicapped by a weak bench. Most Black clubs carried 16 men; the Cubans had only 14. Pitchers got no relief and indeed often played the outfield between starts. LeBlanc started and finished all 18 games for which records could be found and ended with a 13-7 mark. Outfielder Bernardo Barό hit .347. Several years later he teamed with Martin Dihigo and Pablo Mesa to form one of the greatest defensive outfields of all time.

In 1921, Barό played next to Ramon Herrera, who hit .218. Four years later, Herrera would be playing in the American League with the Boston Red Sox, where he batted .385 in 10 games.

Another veteran of the 1906 Giants, John Henry “Pop” Lloyd, had been installed by Foster as manager of the Columbus Buckeyes. Next to the Chicago Giants, the Buckeyes were the weakest team in the league, but Lloyd, then 35 years old, had a great season. He went four-for-four in one game against the Cubans and ended up hitting .337. He also finished third in stolen bases behind youngsters Charleston and Torriente.

The last-place Chicago Giants had only one noteworthy performer, Beckwith. The next year both the Giants and the Buckeyes dropped out of the league.

Several clubs played non-league series against the best Black clubs in the still-unorganized East, teams such as the Philadelphia Hilldales and the Bacharach Giants of Atlantic City

These exhibition games are a bonanza for historians because the only records that are available for the great stars in the East, such as shortstop Dick Lundy, third baseman Oliver Marcelle, and pitcher Cannonball Dick Redding, are for games played against the Western teams. Lundy hit .484 in 17 contests. Marcelle hit .303 in 28 games and Redding had a won-lost record of 7-9.

The Eastern teams would form their own league in 1923, raiding Foster’s circuit of many of its stars, including Charleston, Dave Brown, Mackey, and Lloyd.

Meanwhile, a Black minor league, the Negro Southern League, played its first season in 1921. The Montgomery Gray Sox won the pennant, led by willowy Norman “Turkey” Stearnes, who soon moved up to the Detroit Stars and became one of the great sluggers of Black history.

As the NNL season headed down the stretch early in September, the American Giants still clung to a half-game lead over the Monarchs with six games left between the two leaders. They split the six contests, and Foster’s men went on to win the championship again.

Rube took his team east by private Pullman to the scene of his great exploits with the X-Giants almost 20 years earlier. Against the Hilldales and future Hall of Famer Judy Johnson, Lyons singled, stole second, third, and home. In all, the American Giants stole nine bases, Torriente slugged a homer, and Chicago won the game, 5-2. Tom Shibe, the owner of the park, shook his head. “Now Mr. Foster,” he marveled, “how do you make them move so on the bases?”

Chicago lost the next three games, then played the Bacharachs and split eight decisions with them.

Meanwhile, Charleston and the St. Louis Giants were playing the Cardinals, who won the first game in Sportsman’s Park, 5-4, in 11 innings. The next day Oscar hit a home run to help beat Jesse Haines, 6-2. The Cards won the last three games.

Next Charleston traveled to Indianapolis to play a White all-star squad. He went two-for-four against Brooklyn’s Jess Petty, including a ninth-inning home run that tied the game as the St. Louis Giants went on to win, 8-3. In six games against White Major League pitching that fall, Charleston got nine hits in 27 at-bats with two home runs to climax a great season.

A Statistical Labor of Love

(Editor’s note: Clark and Holway were writing in 1985. To get an idea how far the compilation of Black baseball statistics has come in the meantime, see the Seamheads Negro League Database, which as of January 2020 included a full report on the major Negro Leagues from 1920 to 1948, with other years’ research ongoing.)

The Negro League research project is an on-going labor of love that began around 1975 and has involved many fans, both in and out of SABR (Society for American Baseball Research), who have given of their time, money, and energy.

Batting and pitching statistics occasionally were printed in the Black press, but on inspection they turned out to be suspect. As a result, the SABR Negro Leagues Committee plans to recompile the data for every season, both those with and without published stats.

Negro League research carries problems not faced by other researchers. The records are scattered among many newspapers, both Black and White. Rarely did papers name winning and losing pitchers; these have had to be supplied by researchers using their best guesstimates. Some papers ran box scores without at-bats; these had to be estimated. Others did not include extra-base hits; when possible, these data were obtained from the game accounts. Sometimes all that is available is a line score, and, of course, for some games not even this was shown. Still, enough box scores have been found to begin to build a portrait in numbers of the great men of the Black leagues.

Despite its frustrations, the project carries rewards perhaps not found in other research. This is the last frontier of baseball exploration, a virgin continent of history and heroes as rich as that of the better-known and already well-traveled land of White baseball history.

Among those who have contributed to the project are Terry Baxter, John Bourg and family, C. Baylor Butler, Dick Clark, Harry Conwell, Dick Cramer, Deborah Crawford, Paul Doherty, Garrett Finney, Troy Greene, Richard Hall, John B. Holway, John Holway Jr., Merl Kleinknecht, Jerry Malloy, Joe McGillen, Bill Plott, Susan Scheller, Mike Stahl, and Charles Zarelli.