Phil Schenck: Yankee Stadium’s First Groundskeeper

This article was written by Doug Vogel

This article was published in Yankee Stadium 1923-2008: America’s First Modern Ballpark

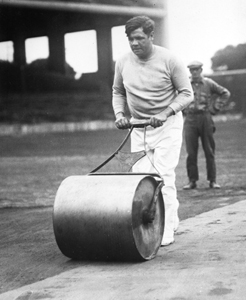

Babe Ruth pitches in to help the grounds crew in The House That Ruth Built. (Getty Images)

November 27, 1922, was an overcast and chilly day, but the grounds crew finished laying the last pieces of outfield sod, pleasing the head groundskeeper. Phil Schenck stood with New York Yankees co-owner Colonel Tillinghast L’Hommedieu Huston admiring the view. Five months earlier, the jovial groundskeeper had promised to have the playing field finished before the first snow fell:

“Sir, I have the honor to inform you that the playing field of this here place is absolutely finished and complete. I herewith hand you the keys to the diamond.”1

Schenck’s handiwork stood out among the remaining unfinished construction at the new Yankee Stadium that was emerging on the banks of the Harlem River. Ten minutes later, it started to snow. By the time Huston and Schenck left the stadium, the turf was covered in a blanket of white powder.2

Phil Schenck had been employed by the franchise dating back to 1903, when they were known as the New York Highlanders. Schenck was hired to build and maintain the new playing field at Hilltop Park in the Washington Heights neighborhood of New York City. He worked tirelessly, maintaining and improving the ballfield for the next nine years, earning him the nickname of the Demon Groundskeeper.3 The local baseball writers featured stories about his magical maintenance methods just as often as they wrote about Highlanders stars Wee Willie Keeler and Jack Chesbro. Schenck’s outgoing personality and portly stature made good copy.

The team outgrew Hilltop Park and signed a 10-year lease to play at the Polo Grounds starting in 1913. On October 5, 1912, the Highlanders played their last game on a Phil Schenck-prepared field, outscoring the Washington Senators, 8-6.4 The ballpark was demolished the following spring. Phil Schenck no longer had a field to maintain.

The New York baseball beat writers now jokingly referred to Schenck as the Groundless Groundskeeper and wrote that he was “the only major league groundkeeper without a ground to keep.”5 He went to work for Henry Fabian, who maintained the Polo Grounds. Schenck was very familiar with the ballpark, having worked there as a kid helping Old Johnny Murphy, Fabian’s predecessor, maintain the place.6 Schenck was now relegated to being a common crew member, but his good nature and strong work ethic were much appreciated.

Schenck was too valuable and too well-liked to be let go outright by the team now known as the Yankees. He remained with the organization and was kept busy as an equipment manager, handyman, and office gofer. When winter came around, Schenck was sent south to prepare the Yankees’ spring-training sites every year, including fields in New Orleans, Shreveport, Brunswick (Georgia), and Jacksonville.7 He faithfully served the team for the 10 years, and welcomed any work the Yankees gave him.8

Schenck’s loyalty paid off in 1922, when he signed a contract to oversee the construction of the playing field for the new Yankee Stadium.9 The groundless groundskeeper would soon have a brand-new baseball field to maintain that he could call his own. “I used to play around this very place when I was a kid,” Schenck reminisced. “I used to swim right where the diamond is now. I was born in the Bronx, only six blocks from here.”10

The construction of the new Yankee Stadium commenced on May 5, 1922,11 and Schenck’s first job was to assist the White Construction Company with installing the internal drainage of the playing field. Properly installed drainage would make the future playing field much easier for Schenck to maintain.12 Some 2,200 lineal feet of four-inch terra cotta tiles radiated in 24 lines from the pitcher’s mound. The tiles connected to the main drain lines leaving the stadium, ensuring a dry playing surface after a hard rain.13 After completing the state-of-the-art drainage, it was Schenck’s turn to fashion the remaining pile of rubble into a verdant, emerald green ballfield like the one his past reputation was built on.

Every detail that would ensure that the playing surface of the new Yankee Stadium was the best in the major leagues was overseen by Schenck. A dedicated staff of laborers whom Schenck would train to become his grounds crew was assembled. Their first task was to install the subsoil to cover the drainage system and create the base for the playing field. The quality of the soil on hand was not up to Schenck’s standards. The crew labored for weeks to sift the piles to remove the large rocks, tree roots, and grass clumps before spreading it evenly across the future stadium floor. A two-ton roller firmed the hand-graded soil before a nine-inch layer of topsoil was spread on top of the base. Horse manure and limestone were tilled into the topsoil to enrich the growing medium. Fertilizer was carefully applied after hand grading and rolling was completed.14 The field was now ready to transition from a flat, dirt construction site to a glorious baseball diamond.

The infield was built on Schenck’s perfectly graded field. It was designed by the engineers of the Osborn Engineering Company.15 Schenck called it the “turtleback mound” because it looked like a shell of a large tortoise. He didn’t like the height of the mound, and he didn’t like the turf beyond the track that ramped up to the outfield fence, either. He vowed to replace them both, but the big pimple would remain for now.16

Schenck visited five neighboring states searching for the perfect turf to cover his diamond. He chose the 160,000 square feet of sod for the infield and outfield from a secret source on Long Island.17 The green squares were laid out, rolled for smoothness, and carefully watered daily to prevent desiccation until all the truckloads were unloaded and laid. Fresh grass seed was spread over the sod, raked in, and rolled again to ensure a thick, healthy playing surface.18

The final details were checked off the punch list one at a time. The infield skin was raked repeatedly until no stone bigger than a “mosquito’s eye” remained.19 The pitcher’s rubber and home plate were set in concrete. A 1,000-pound gas-powered Coldwell Model H lawn mower that both cut and rolled the grass to help maintain a firm and true playing surface was purchased.20

The stadium also included a 400-yard, 24-foot-wide running track with red cinders that encircled the playing field and was an added feature for Schenck’s crew to maintain. Designed by Frederick W. Rubien of the Amateur Athletic Union, it was the venue for track and field meets sometimes held when the Yankees were on road trips.21 By late fall, Schenck’s installation was complete. “I’ve worked night and day on it. I’m glad it’s over,” he said. “I’m going home to bed now and leave a call for February 4.”22

The grand opening of the stadium was set for April 18, 1923, and Phil Schenck’s reputation as the top groundskeeper in the major leagues was once again on full display. The tarp that covered Schenck’s masterpiece over the winter was removed to reveal an emerald green turf, just as expected. The warmth from the tarp duped the grass into an early spring green-up, one of the many tricks the Demon Groundskeeper kept up his sleeve. The Yankees and the visiting Boston Red Sox both held brief workouts on the pristine sod the day before the grand opening. “So far, no spikes have dented the new turf carefully laid by Phil Schenck last fall,” wrote Fred Lieb in the New York Evening Telegram.23 Schenck would soon find out he would need all the tricks he could muster and learn a few more new ones to help in the maintenance of the new ballpark.

Wear and tear were Phil Schenck’s greatest adversary, and it commenced on Opening Day. Participants in pregame festivities including John Philip Sousa and the Seventh “Silk Stocking” Regiment Band, local politicians, baseball dignitaries, the Yankees and Red Sox players, cameramen, and sportswriters all herded across the manicured turf.24 The sellout crowd of 74,200 exited across the field after the Yankees handed the Red Sox a 4-1 loss featuring a three-run Babe Ruth stadium-christening clout.25 The extra foot traffic was a cost of doing business for the opening of the grandest stadium ever built, and it was a welcome sight to Schenck, who was more than happy to make any repairs.

Maintenance of the new stadium wasn’t going to be about preparing for just baseball games. Yankee Stadium was designed as a multipurpose stadium with the ability to generate revenue when the Yankees were away and during the offseason as well.26 This greatly added to Schenck’s workload. During the 1923 season, the assault on Schenck’s masterpiece included 76 regular-season Yankees home games, three World Series home games, Tex Austin’s Rodeo, championship boxing matches, AAU track and field events, and college and local football games. “I figure that a million and a half people scruff across this lot every year,” Schenck said.27

The rodeo came to town on August 15 for a 10-day engagement and proved to be a huge headache for Schenck during the stadium’s maiden season. “Matting at a cost of $25,000 was laid over the infield grass at the behest of the stadium management but at the rodeo’s expense. When the matting was removed at the end of the rodeo, the all-important infield grass was seen to be a dried-out yellow swatch.”28 Schenck had five days to work his magic on repairing the field. The Yankees returned to the stadium after an extended 17-day, 12-game road trip to find Schenck applying a special tobacco-based fertilizer that he sourced from Scranton, Pennsylvania.29 The “secret blend” jump started the greening-up process of the yellow turf. The rodeo never returned to the stadium during Schenck’s tenure.

The 1923 World Series between the Yankees and the New York Giants provided Schenck the opportunity to showcase his field against his cross-river rival Henry Fabian of the Polo Grounds. Schenck had Yankee Stadium in as good shape as was humanly possible for Game One after seven months of baseball games and extracurricular wear and tear. Photos of the day show a well-worn but manicured field.30 The Yankees won the deciding Game Six at the Polo Grounds, sparing Schenck’s field the abuse of a championship celebration. For all his hard work, the players voted Phil Schenck a $750 share of the World Series winnings.31

Proactive maintenance was the benchmark of Schenck’s program: “After every baseball game and between periods of a football game my men hunt out every new scar and sprinkle it with a mixture of seed, humus, bone meal and sheep manure.”32 By the end of the grass-growing season, the continued use of the field took its toll, regardless of how much care was given. Schenck said, “During the fall, professional football teams practice here most every day, rain or shine, and they sure tear up the turf.”33 In spite of the grounds crew’s herculean efforts, by the end of every football season, the field was always in need of new sod the following spring.

The spring of 1924 found Schenck eliminating what he felt was poor design. “Phil Schenck, the rotund Stadium ground keeper, has been busy all winter working on his new field,” a sportswriter commented. “The open winter has been a big help to him. The diamond has been completely remodeled and rebuilt. The new diamond will not be the turtle-back in as far as of last season.”34 Schenck flattened the infield diamond and lowered the pitcher’s mound. He installed red clay around home plate to keep the players from “digging in,” a practice that left holes and created constant maintenance issues. After finishing the repairs to his field, Schenck’s second task was to oil up and clean the large Seth Thomas clock on the stadium scoreboard. It sat dormant all winter until Schenck climbed up the bleachers and performed the annual winding. The Yankees didn’t “officially” start their season until the clock was running.35

Everyone had a Babe Ruth story to tell, and Schenck was no different. He had plenty of them, but the one he liked to recount was the day The Babe hit an inside-the-park home run against the Cleveland Indians in 1924. Schenck and his friend Henry Fabian watched Ruth crush a Dewey Metivier pitch a claimed 592 feet to dead center field.36 Fabian laughed, not at the ball that came up short of the fence, but at the divot that the ball sent flying. Ruth raced around the bases for the unlikely home run. Schenck gladly repaired the divot after the game.

Football games at the stadium were played in all weather, rain or shine. The concentrated wear of football cleats tearing up dormant turf put a yearly end to anything being associated with the field looking manicured. The 1926 season opener of the New York Yankees of the old American Football League became a nightmare for Schenck. The field had received 24 hours of rain the previous day and it continued throughout most of the game. Star Red Grange and the Yankees hosted the Los Angeles Wildcats. The Galloping Ghost was hampered by the soft field, mustering only two 15-yard runs as the field was reduced to a miniature swamp. “After a few minutes of scrambling around in the muck and mire of Phil Schenck’s beloved ballfield, everyone was covered in mud and you couldn’t read the numbers from one another,” a sportswriter reported.37 The football Yankees won 6-0.

The Jack Dempsey-Jack Sharkey boxing match held on July 21, 1927, in midseason, would prove to be Schenck’s greatest challenge to repair. The Yankees were set to return for a doubleheader with the St. Louis Browns on July 26, giving Schenck five days to work his magic. “See the square where the border is a little light colored?” Schenck mentioned to a writer after the season. “That’s where the ring was for the Dempsey-Sharkey fight. The reporters and excited fans in the ringside seats scraped their feet and wore off the grass. Wherever there were seats on the ground we found bare patches the next day.”38 To the delight of Schenck, the Yankees wore out only the basepaths, scoring 27 runs in the doubleheader.39

Twelve days before the 1928 home opener, the beloved Phil Schenck died suddenly at home.40 The Yankees were in a pinch but had to look no farther than across the Harlem River and hired Walter Owens, the assistant groundskeeper of the Polo Grounds.41 Owens had trained under the watchful eye of Schenck’s good friend Henry Fabian and was more than qualified to fill Schenck’s big shoes. His first task was to prepare Schenck’s ballfield for the home opener against the Philadelphia Athletics. His preparations for his first game as a head groundskeeper included extra pregame grooming for the ring ceremony and championship banner raising of the 1927 World Series winners.42 Owens labored with great success as the Yankees’ head groundskeeper for the next 24 years. The Demon Groundskeeper’s legacy was in good hands.

DOUG VOGEL is a lifelong baseball and golf fan. He has made a living as a golf-course superintendent for the past 32 years. Doug is a credentialed press member of the PGA Tour, the PGA of America, and the United States Golf Association and covers major golf tournaments with an emphasis on golf course tournament preparation. He is a past editor of The Greenerside, an award-winning newsletter published by the Golf Course Superintendents Association of New Jersey. Doug is well known for writing articles that have combined golf and baseball story lines. He recently published his first book, Babe Ruth and the Scottish Game – Anecdotes of a Golf Fanatic. The New York Mets and the New Jersey Jackals are his teams.

AUTHOR’S NOTES

The author would like to recognize the importance of reference librarians. The staff of the Wayne Township (New Jersey) library consistently fill obscure requests, provide any and all assistance needed, and do it with a smile. Also, a big thank you to Andy Stamm, librarian at the United States Golf Association Museum. His timely correspondence answered a lot of questions.

The terms groundskeeper and groundkeeper were both used by sportswriters during this period. Dan Cunningham, the current Yankee Stadium turfgrass expert, has the title of head groundskeeper.

Golf course architect William H. Tucker’s obituary noted that he “put in the turf of the original Yankee Stadium.”43 In the book The Architects of Golf the authors wrote, “Tucker was a nationally known turfgrass expert and had been called upon to install the original turf at such sports facilities as Yankee Stadium and the West Side Tennis Club.”44 It is well documented that Phil Schenck installed the sod at the new Yankee Stadium. Tucker’s name never came up connecting him to any phase of the project in any newspaper archives searched. His involvement remains a mystery.

NOTES

1 John Kieran, “Infield at Yankee Stadium Completed as Per Schedule,” New York Tribune, November 28, 1922: 14.

2 James Crusinberry, “Yankee Diamond Tucked in for Winter Sleep,” New York Daily News, November 28, 1922: 28.

3 W.O. McGeehan, “Pinochle Ousts Baseball in Camp of the Yankees,” New York Tribune, April 12, 1919: 21. “Phil Schenck, the Demon Ground Keeper, will precede the team to each burg, by twenty-four hours and iron out the different diamonds.”

4 1912 New York Highlanders Statistics, Baseball-Reference.com, baseball-reference.com/team/NYY/1912.shtml, Accessed July 17, 2022.

5 “Sure Sign of Spring,” Washington Times, February 18, 1922: 9.

6 Will Wedge, “Yankee Clock Starts Ticking,” Baltimore Sun, March 3, 1924: 33. Johnny Murphy was the groundskeeper before Henry Fabian.

7 W.O. McGeehan, “Hannah and Schneider Join at Jacksonville,” New York Tribune, March 25, 1919: 19. Preparing spring training fields kept Schenck busy for various reasons. The circus wintered on the Southside Ballpark field before the Yankees’ arrival. “Phil Schenck is still telling of the engineering feats he accomplished in filling the elephant tracks.”

8 “Allen Russell Quits Yanks,” Paterson (New Jersey) Evening News, July 18, 1918: 10. Schenck worked for the Yankees in multiple capacities after losing his Hilltop Park groundskeeper position. “Miller Huggins … had left word with Phil Schenck, the clubhouse man, to pack up his belongings and send them to Baltimore where Russell lives.”

9 “Phil Schenck to Make New Diamond for Yanks,” Washington Times, August 3, 1922: 16.

10 Wedge: 33.

11 Different starting dates found include May 6, 1922. Michael P. Wagner, Babe’s Place: The lives of Yankee Stadium (Akron:48HrBooks, 2017), 15. “Limited construction didn’t actually begin until May 6.”

12 Harry C. Butcher, “Good Farm Practice Has Helped the Yankees Win Their Pennants,” Fertilizer Review, October 1927: 10-11. Schenck remarked, “Our drainage system made it possible for us to play the fourth game in the World Series with Pittsburgh.”

13 “Yankee Stadium, New York,” Architecture and Building, May 1923: 49.

14 Butcher, 11.

15 “Fabian Dean in His Line,” Auburn (New York) Citizen, August 15, 1928: 5. The Osborn engineers were simply copying what was a common construction technique of the era. “Henry Fabian, dean of the groundskeepers, constructed the first turtleback baseball field in Dallas in 1889.” Other ballparks that Osborn Engineering built include Boston’s Fenway Park and Chicago’s Comiskey Park.

16 Frederick G. Lieb, “Yankee Diamond Has Been Moved,” New York Evening Telegram, February 3, 1924: 14. “The new diamond will not be the turtleback affair of last season.”

17 Kieran, 14.

18 Butcher, 11.

19 Kieran, 14.

20 “An Effective Power Mower,” American City Magazine, July 1925: 113.

21 Al Copland, “News Marathon Track All Set for New Record,” New York Daily News, April 24, 1923: 23. The Daily News Marathon of May 20, 1923, was the first track event held on the new Yankee Stadium track.

22 Kieran, 14.

23 Frederick G. Lieb, “Shawkey to Pitch Opening Contest,” New York Evening Telegram, April 17,1923: 4.

24 “Biggest Ball Park Opens Gates Today,” New York Daily News, April 18, 1923: 22.

25 1923 New York Yankees Statistics, Baseball-Reference.com, baseball-reference.com/boxes/NYA/NYA192304180.shtml. Accessed July 24, 2022. Baseball-Reference.com lists the Opening Day crowd as 74,200 while most newspapers used the 75,000 official seating capacity in their reporting.

26 “Yankee Stadium, New York.” “The field is also suitable for other athletic events and there is a cinder running track about it.”

27 Butcher, 10.

28 Tom O’Connell, “Vet Rodeo Mgr. Frank Moore Eschews Tools of the Trade,” Billboard, October 21, 1950: 58, 63.

29 Will Wedge, “Tobacco Fertilizer,” New York Sun, March 3, 1925: 33.

30 1923 World Series Recap, MLB.com, mlb.com/news/1923-world-series-recap. Accessed October 1, 2022. Photo of Casey Stengel sliding into home during Game One at Yankee Stadium shows extensive wear to the home plate/baseline area.

31 “26 Yankees Each Receive $6,160.46,” New York Times, October 17, 1923: 16.

32 Butcher, 10.

33 Butcher, 10.

34 Frederick G. Lieb, “Yankee Diamond Has Been Moved,” New York Telegram and Evening Mail, February 3, 1924: 14.

35 Wedge, 33.

36 Will Wedge, “Ruth’s Cruel Homer,” New York Sun, July 21, 1924: 20. Ruth’s blast of 592 feet is either a printing error or yellow journalism. The correct 1924 measurement was 490 feet to dead center. Yankee Stadium, Clem’s Baseball, andrewclem.com/Baseball/YankeeStadium.html#diag. Accessed October 25, 2022.

37 Leonard Cohen, “New York Yankees Beat Wildcats, 6-0, on Tyron’s Sprint,” New York Evening Post, October 25, 1926: 15.

38 Butcher, 10.

39 1927 New York Yankees Statistics, Baseball-Reference.com, baseball-reference.com/teams/NYY/1927-schedules-scores.shtml. Accessed July 24,2022

40 “Yankees First Groundkeeper Dies,” Syracuse Journal, April 10, 1928: 13. The Yankees had initiated a spring-training regimen three years earlier to help the “rotund” Schenck lose weight. Will Wedge, “Phil Schenck in Training,” New York Sun, February 4, 1925. “Phil Schenck, the sod shampooer of the Yankees, has been dispatched to St. Petersburg to prepare for the coming season. Schenck will not only prepare the ball yard for the Ruppert Rifles but he will also prepare himself physically. Doc Woods, Yankee trainer, will supervise Schenck’s course of conditioning exercises.” No formal obituary of Schenck made the papers.

41 Dr. Ken Kurtz, “An Inning From Our Past,” Sports Turf Manager, July/August 2003: 7-14.

42 Frank Wallace, “Cobb’s Ghost Covers Right Field,” New York Daily News, April 21, 1928: 29. “Each Yankee received a blue diamond in a ring as a reward for winning the world series.”

43 Obituary, New York Times, October 8, 1954: 23.

44 Geoffrey S. Cornish and Ronald E. Whitten, The Architects of Golf (New York: HarperCollins Publishers, Inc. 1993), 419.