Philadelphia, October 1866: The Center of the Baseball Universe

This article was written by Jeff Laing

This article was published in The National Pastime: From Swampoodle to South Philly (Philadelphia, 2013)

In the late nineteenth century, Philadelphia was a hotbed of baseball activity, and specifically of idiosyncratic match-ups. For three weeks in October 1866, Philadelphia was the scene of two “world” championship series that helped determine the future course of baseball in the areas of professionalism and race.

The 1860s were a decade of rapid social change and radical perceptions of what it meant to be an American. The growth of the railroads and affordable train travel; the development of communication services, such as the telegraph and the typewriter; and the end of the Civil War all aided in the growth and development of baseball into a shared national experience. The game was simple to understand, inexpensive, relatively easy to play, and, according to its most vocal proponents, American in origin and nature. With little competition from other team sports, baseball in the 1860s stepped into a nation searching for a means of reunification and dedication to American ideals.

Baseball was also ubiquitous in this era as a part of many school physical education programs because it was cheap to fund—a ball and a bat—with many possible participants. The US Military used the game to develop physical strength and dexterity, mental agility, and team cohesion while sharpening the soldiers’ competitive skills. Local baseball associations developed personal camaraderie and civic devotion to town teams. The notion of baseball as a patriotic activity began in this decade and the flag was often presented by local groups to visiting clubs.

The 1866 Championship Match, a best of three affair scheduled for early October, between the six-time eastern champion Atlantics of Brooklyn and the up-and-coming Athletics of Philadelphia who arranged the competition, was a major event in the evolution of baseball into a professional sport: “The October 1866 series…was, to that point, the culmination of enticing players, arranging tours, promoting matches between top clubs and charging the public, all to maximize profit.”1 The first game was scheduled for October 1 at the Columbia Avenue and 15th Street grounds. Though there had been an advance sale of 8,000 tickets at 25 cents, Philadelphia was not prepared for the crowds that showed up for the ball game. The estimated attendance was in excess of thirty thousand spectators, many of whom were herded to the outfield. When the police force proved insufficient to the task of removing the fans from the playing field, the game was called in the second inning.2 The Philadelphia papers went into a paroxysm of excess about the possibility that a fervid devotion to baseball by half-crazed cranks would lead to the eventual demise of the sport:

Yesterday the base-ball fever culminated in a scene disgraceful to Philadelphia. The much-talked of game between the Athletics and Atlantics was prevented by the ignorant conduct of the vast crowd assembled to witness the sport. We do not overestimate when we say there were 30,000 people present, and of those 30,000 a large proportion lacked common sense. In their eager desire to secure advantageous positions, they sacrificed all propriety, and overreaching themselves, prevented the game which they all had come miles to see. It is a matter of extremely slight importance whether the game in question occurs or not, but an instructive lesson can be drawn from the conduct of those present on the occasion, We stated yesterday that the admiration felt for base-ball as for all physical sports, was a natural one; that it should be popular is proper. But at the same time we warned all lovers of the game that the excess to which it was being carried would prove its ruin.

The reporter discussed in depth the twin dangers that threatened baseball’s growing popularity: gambling and drinking. The article concluded with an appeal for moderation among all elements of fandom:

We like the game of base-ball. We think it calculated to strengthen the muscles, invigorate the system, and counteract the evils of the sedentary life lead [sic] by some many of our young men. But at the same time it would be better to have no game than what we fear it will become. Let the nuisance be abated, for nuisance it has become. Let us have it in moderation; for as long as the fever does not cool, the whole sport will be ruined, and base-ball and cricket rank among the things that were.3

On October 15 in clear weather conditions, the return match at the Atlantics’ Capitoline Grounds in Bedford, New York, was played with the home team winning, 27–17, after a close match through the first four innings. Equally important, the Brooklyn ownership organized the game effectively by decorating the 4,000-seat stadium in patriotic colors, selling no tickets in advance but insisting that all spectators that entered the grounds pay a quarter by exact change, providing dignitaries with special seating, and having a small army of police to ensure order with the crowd estimated to be in the neighborhood of 20,000.4

With the revenues from the first two meetings—the aborted game on October 1 ($2,000) and the Atlantics victory on October 15 ($1,000)—totaling $3,000,5 the 1866 series was turning out to be a financial if not artistic success. The third (and what turned out to be the final) game of the series took place back in Philadelphia on October 22. The Athletics were much better prepared for the anticipated fan interest with a stronger police presence and a new fence built around their field to limit the attendance to 4,000 paying spectators. To increase profits, the Athletics charged a dollar a ticket, an exorbitant, previously unheard-of fee to attend a baseball game.6 The actual game followed the same pattern as the October 15 match with a close game becoming a blowout for the home team in the later innings. Philadelphia outscored Brooklyn, 22–3 in the last three frames, before a downpour ended the game in the eighth inning with the Athletics leading 31–12.

A final deciding game was never played in this series due to a money dispute: The Athletics wanted to take the cost of their newly erected fence off the top of the revenues while Brooklyn wanted to share in the total gross profits.7

While the 1866 Match series was inconclusive in declaring an eastern champion, it did prove that there was enormous fan interest in championship level baseball and that a great deal of money could be made from such games, suggesting that baseball in the near future was a potentially solid business investment and profit-maker.

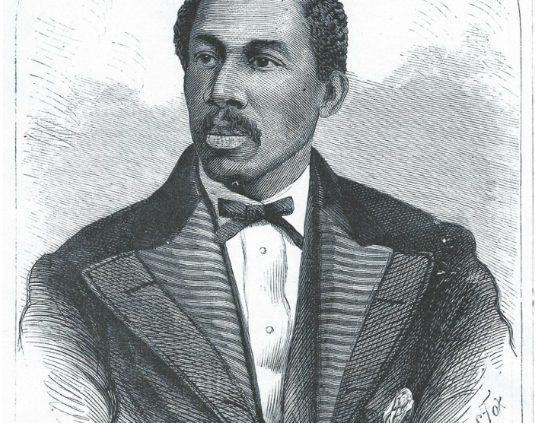

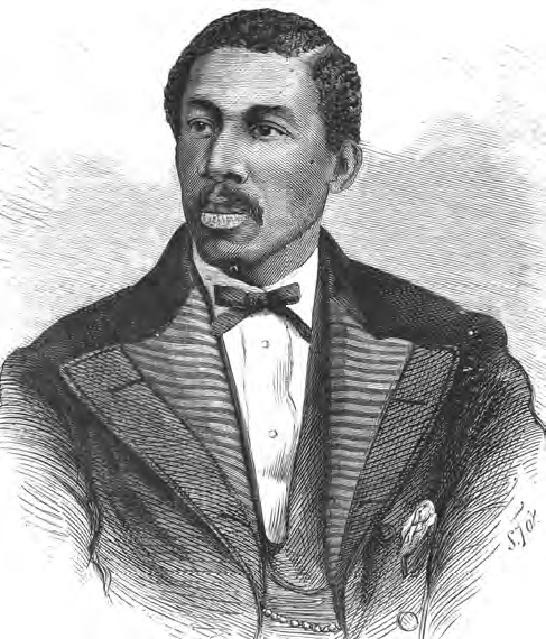

Civil rights activist Octavius C. Catto founded the Philadelphia Pythians in 1866.

During the same week that the Atlantics were facing off against the Athletics, the African American Albany (New York) Bachelors came to Philadelphia and laid claim to the first (unofficial) black baseball championship

Early in October the Albany Bachelor Base Ball Club headed the 260 miles south to Philadelphia to challenge the newly established black Excelsior and Pythian clubs. Eager to spread the gospel of baseball to African American organizations and communities, the Bachelors paid their own expenses and had a successful first-ever road trip for a black ball club. On October 3, 1866, the Bachelors met the Pythians at the Parade Grounds at 11th and Wharton Streets near the Moyamensing Prison.8

The Philadelphia Pythian Base Ball Club was founded in 1866 by civil rights activist and base ball star infielder Octavius V. Catto who recruited 50 percent of his middle class team from the Banner Institute (a literary and debating society that shared rooms with the ball club).9 Catto’s vision for the club was always larger than the won-loss column. He desired “equal participation and recognition” for African Americans in American society. He himself was instrumental in desegregating the city trolley cars. He believed base ball “built community ties, pushed racial boundaries, and established local and national networks of support.”10 (The Bachelors were led by a similarly motivated leader, James C. Matthews, who became the New York State Recorder on the Democratic ticket in 1895, and saw the national pastime as a means for African Americans to strive for equality.11)

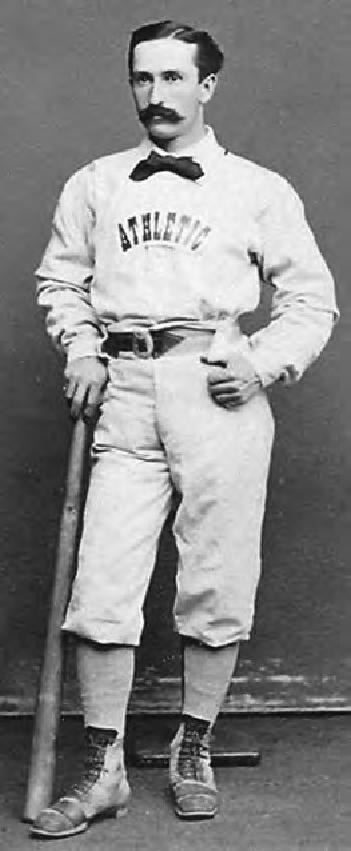

This 1874 photo depicts Weston Fisler, who joined the Athletic Club of Philadelphia in 1866.

The result of the October 3, 1866, match game was a rout in favor of the Upstate New York visitors. The Albany Evening Journal was quick to reprint the results of the game: “Oct. 3—Philadelphia: A match game of base ball was played this P.M. between the Bachelors of Albany and the Pythians of this city, which resulted in a victory for the former by a score of 70 to 15.” The Syracuse Daily Standard (October 4, 1866) published the fact of the Bachelors’ victory and added that “this game attracted a large crowd of spectators.” Word of the Albanians’ resounding defeat of the Pythians was also reported in the Nashville Daily Union and American (October 4, 1866): “Philadelphia, Oct. 3—A match was also played between two negro [sic] clubs, the Bachelors of Albany, and the Pythians of this city [Philadelphia]. This game attracted a large number of spectators.”

On the following day, the Albany Evening Journal reported another solid diamond victory for the Bachelors: “Philadelphia, Oct. 4—Another match was played this P.M. between the Bachelors of Albany and Excelsiors of this city, which resulted in another victory for the Bachelors, by a score of 44 to 28.”

In 1867, the Pythians baseball club went 9–1. Trying to follow up on their on-field success, Catto’s club unsuccessfully attempted to participate in the Pennsylvania Convention of Baseball in Harrisburg on October 16 and, despite the support of Athletics of Philadelphia vice-president and president of the nominating committee E. Hicks Hayhurst, the Pythians were the only one of 266 clubs denied entry into the association. Later in the fall, the National Association of Base Ball Players (NABBP) upheld the Pennsylvania decision.12

In spite of their failure to enter organized baseball, Catto’s Pythians were a major force in the attempted integration of the national pastime. The high visibility and political astuteness of its founder and the integrity and skill of its club members provided the Pythians a place of prominence in early black baseball’s fight against racial bias. Yet, by the fall of 1867, less than two years after the conclusion of Civil War, baseball had officially established a color line that was not to be lifted on a full-scale basis for 80 years.

Within a few weeks of each other in 1866, two major baseball competitions were held in Philadelphia that would lead to radical changes. Baseball was becoming America’s national pastime and a viable profession for talented players; the game was also doing so without the inclusion of African Americans. Money matters and racial prejudice, national issues that remain unresolved to this day, thus dominated the earliest years of our national pastime.

JEFFREY LAING is a retired English teacher who has published more than 150 articles on arts and culture, pedagogy, and sports. His baseball writing has appeared in “The National Pastime,” “Fan Magazine,” “Base Ball: A Journal of the Early Game,” and “Black Ball: A Negro Leagues Journal.”

Notes

1. Preston D. Orem, Baseball 1845–1881 from Newspaper Accounts, 54–55, cited in Eric Miklich’s “Money Ball: 1866 Championship Match—Athletics vs. Atlantics” The Base Ball Players Chronicle: 1–13. http://vbba.org/newsletter/?p=36. (Accessed 10/20/2012).

2. Ibid, 2–3.

3. Philadelphia Evening Telegraph (PET), October 2, 1866, 4.

4. Miklich, 4.

5. Ibid, 5.

6. Ibid.

7. Ibid.

8. Jerrold Casway, “Octavius Catto and the Pythians of Philadelphia,” Historical Society of Pennsylvania: www.hsp.org/print/node/2931.

9. George B. Kirsch, Baseball in Blue and Gray: The National Pastime during the Civil War (Princeton University Press, 2003), 128.

10. “Playing for Keeps: The Pythian Base Ball Club of Philadelphia,” Historical Society of Pennsylvania. www.hsp.org/node/2937.

11. The Hamilton (Marion County, AL) News-Press (HNP), November 14, 1895.

12. For a comprehensive discussion of the life and untimely political murder of Octavius Catto and his Pythian Club SEE the following articles: Daniel R. Biddle and Murray Dubin, “An Early Quest for Equality on the Diamond,” philly.com: 1–6. www.printthis.clickability.com/pt/cpt?action=cpt&title (Accessed 9/16/3010); Jerrold Casway, “Philadelphia’s Pythians,” The National Pastime, 120–123; “On the field, the Pythian Club…,” Philadelphia Baseball Review: 1–2. www.philadelphiabaseballreview.com/pythian2.html. (Accessed August 20, 2011).