Point Men: First MLB Players Born in Each Decade of the 20th Century

This article was written by Larry DeFillipo

This article was published in The National Pastime (Volume 25, 2005)

Major league baseball relies on a steady infusion of fresh talent in order to retain its vitality and popularity. Young players of each generation make their mark on the sport and then move on, replaced by the next. The point men of each generation, the very first to reach the major leagues, have often carried great expectations and met with mixed results. Using each decade to represent discrete generations, these point men can be identified and their stories told. While selecting other generational markers would produce a different set of point men, the careers of these players offer a fascinating look into the events and personalities of each generation.

THE ROSTER

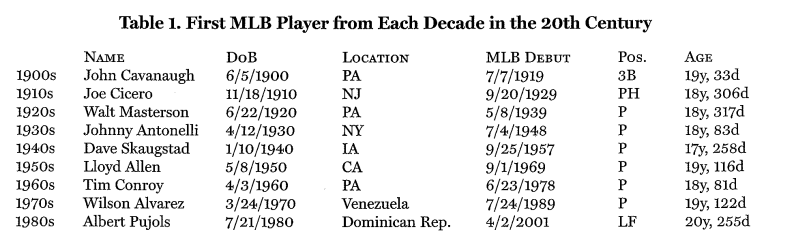

Table 1 lists the first player born within each decade of the 20th century to play in a major league game.1 Of course no player born in the 1990s has yet graced a major league roster. The list is a mix of modestly accomplished players, short timers with names unrecognizable to even contemporary fans, and perhaps the most talented young hitter of today, Albert Pujols.

As expected, these point men began their careers at a very young age. Only Albert Pujols began his major league career after his 20th birthday, with the youngest, Dave Skaugstad, appearing in his first game well shy of his 18th birthday. The birthplaces of these players reflect the shift in where the typical major leaguer originates-the Mid-Atlantic States in the first third of the 20th century, Midwest/western states in the middle of the century and Latin America in the past two decades.

THE 1900s

The first player born in the 1900s to appear in a major league game was John Cavanaugh, born in Scranton, PA, in the spring of 1900. Cavanaugh played in only one major league contest, for the 1919 Phillies. Substituting at third base in the late innings of a July 7 contest at the Polo Grounds, Cavanaugh struck out in his only at-bat against Giant ace Jesse Barnes, the NL’s winningest pitcher in 1919. The Phillies were swept in a doubleheader that day, enabling the Giants to briefly regain first place in their National League pennant race with Cincinnati. The Redlegs would go on to win the NL crown and face the Chicago “Black” Sox in the World Series.

While Cavanaugh was to play only this single game for the Phillies, it was notable for a record set that day that has not been equaled since. In the bottom of the ninth, trailing by eight runs, the Phillies mounted a valiant comeback against Giant reliever Pol Perritt. The comeback fell short as the Phils managed only three runs but in one stretch, four consecutive Phillie batters reached base on three hits and a walk. Each of those base runners (Luderus, Sicking, Cady, and Cravath) in turn stole both second base and third base-stealing a total of eight bases in a single inning. Newspaper accounts describe the Giants as indifferent to the base-running antics of the Phillies, suggesting that modern rules would not award a single stolen base in a similar situation today. Nonetheless, on the day the first player born in the 20th century participated in a regular season major league game, the 1919 Phillies broke the NL record (and tied the major league record) for stolen bases in an inning.

What exactly happened to Cavanaugh after his debut has not been documented. That very evening, with an ugly 18-43 record and having lost 11 consecutive games, Phillie manager Jack Coombs was fired by owner William F. Baker.2 Coombs was replaced by outfield star Gavvy Cravath, who immediately announced his desire to upgrade the team’s talent level, kicking off a wave of trades and player releases.3 John Cavanaugh may well have been caught up in Cravath’s whirlwind effort to return to the glory of Philadelphia’s 1915 NL Championship season. Cavanaugh resurfaced with a Scranton semipro team later that year (the “Uniques”), while the Phillies finished securely in last place, not to win another title for 31 years.

THE 1910s

Joe Cicero was both a cousin of actor Clark Gable and the first player born in the 1910s to reach the majors. The Atlantic City, NJ, native joined the Red Sox squad in the spring of 1928 as a 17-year-old shortstop. He began the season with the club but was optioned to Salem of the New England League on June 1 without playing in a single game. The following year Cicero was promoted from Pittsfield to the Red Sox in mid-September, making his major league debut on September 20, 1929. Cicero delivered a pinch hit single in a 4-2 loss to the Cleveland Indians, followed up nine days later by a three-hit, three RBI performance in a 10-0 whitewashing of Lefty Grove and the AL champion Philadelphia Athletics. This was to be Joe Cicero’s most prodigious major league performance. Used sporadically in the 1930 season, he was sold to the Indianapolis Indians and resumed what was to be a lengthy minor league career.

Joe Cicero did not return to the baseball limelight until 14 years later, when he made headlines as a wartime member of the famed Newark Bears. In the 1944 opening day contest against the Montreal Royals, left fielder Cicero drilled three home runs, including two grand slams and delivered 10 RBI in a 17-8 victory. This game was a likely springboard to the next, and most improbable, chapter in Cicero’s career. Faced with wartime shortages of baseball talent, Connie Mack invited Cicero to spring training in 1945 with his Athletics squad. Cicero was the ”hit” of the A’s camp, “with his booming drives over the left-field fence.”4 And so the bespectacled Cicero began the 1945 season as the Philadelphia A’s starting left fielder-15 years after last appearing in a major league game. He did not hit well against regular season pitching though, batting only .158 in a dozen games for the last-place A’s. Joe Cicero played his last game in May 1945, a few weeks after VE Day, as ballplayers began returning from military service around the globe.

THE 1920s

Walt Masterson, first player born in the 1920s to reach the majors, was impressive in spring training outings for the 1939 Washington Senators as a reliever for manager Bucky Harris. The 18-year-old Philadelphia native impressed AL President William Harridge enough to be included in an article he authored on the eve of opening day in which he previewed the upcoming season. Masterson was listed alongside Ted Williams, Charlie “King Kong” Keller, and Bill Rigney as the class of 1939’s most promising rookies.5 Masterson opened the season at Charlotte but was quickly called up to the Senators in late April, making his first appearance on May 8 in relief against the Cleveland Indians. The young right-hander pitched a shaky eighth inning, allowing two walks and one hit but no runs in a 6-2 loss.

After another brief outing in relief, Masterson was given his first major league start on May 18 against the Detroit Tigers. Masterson’s mound opponent was veteran Buck “Bobo” Newsom, acquired days earlier from the St. Louis Browns in a 10-year deal. Winner of 20 games for the seventh-place Browns in 1938, Newsom would go on to again win 20 games in 1939 and then post a brilliant 21-5, 2.83 ERA season as a workhorse for the AL champion Tigers in 1940. But Masterson spoiled Newsom’s tiger debut, throwing a 4-1 complete-game victory for the Washington Senators in Griffith Stadium. Masterson scattered six hits while walking six and striking out seven, the only Tiger run set up by a wild throw by Masterson himself on a ball hit by Newsom. The rookie held Tiger stars Charlie Gehringer on three straight curveballs with two men on in the ninth to secure the win. Walt Masterson would pitch for 14 years with the Senators, Red Sox, and Tigers, compiling a 78-11 record. He was selected to start in the 1948 All-Star game in what was surely the highlight of his career but was unlucky enough to be a part of two record hitting streaks during his career. On June 29, 1941, Joe DiMaggio collected a seventh-inning single off Masterson to break George Sisler’s 41-game AL consecutive-game hitting streak record. In July 1952 the Red Sox’s Walt Dropo went 4-for-4 against Masterson in the first game of a doubleheader with the Senators. Before the second game was over Dropo had collected 12 consecutive hits, setting a new major league record.

THE 1930s

John August (Johnny) Antonelli, one of the first ”bonus babies,” was also the first major leaguer born in the 1930s. The 18-year-old left hander signed with the Boston Braves for $65,000 on June 30, 1948, reputedly the largest bonus paid to that point for any player. A week later Antonelli made his debut for Boston on the road against the Philadelphia Phillies in the first half of a July 4 doubleheader. Relieving in the eighth inning, Antonelli allowed one run on two hits (to Richie Ashburn and Del Ennis) in one inning of a 7-2 loss to the Phils. The nightcap of the holiday doubleheader featured the fourth career start and third lifetime win for Phillie rookie and fellow bonus baby hurler Robin Roberts.

Antonelli pitched only three more games in 1948 for the NL champion Braves, earning a save while allowing no hits and no runs. He did not appear in Boston’s World Series loss to Lou Boudreau’s Cleveland Indians but was awarded a partial share ($571.34) of the World Series losers’ bonus money. Antonelli’s portion was decreed by baseball commissioner Happy Chandler6, overriding his teammates’ decision not to award him a cut of the money.

After three years with the Braves as an occasional starter, Johnny Antonelli joined the military for two years, serving in Korea. Prior to the 1954 season he was traded to the New York Giants in a controversial deal for center fielder Bobby Thomson, hero of the 1951 Miracle at Coogan’s Bluff. Antonelli would go on to a 21-7 record in 1954, leading the NL in ERA (2.30) and the Giants to a World Series sweep over the Cleveland Indians. He started and won game two over tribe ace Early Wynn and delivered a game four save in relief. Antonelli earned a full $10,795.36 winners’ share for his efforts.

In a game remembered by many New Yorkers as vividly as his World Series performances, Johnny Antonelli started and lost the final game played by the Giants in the Polo Grounds on September 29, 1957. He suffered a 9-1 shellacking by the Pittsburgh Pirates, after which Giant fans poured on the field in search of souvenirs, stealing home plate, the bases, and even a center-field monument to Giant infielder Eddie Grant, killed in action during World War I. After four All-Star appearances and winning 108 games for the NY/SF Giants, Antonelli split his final season in 1961 between the Indians and Braves-opponents in the 1948 World Series. Following the end of the season, Milwaukee sold his contract to the expansion New York Mets. Johnny Antonelli elected to retire rather than report, ending his career with the team that first signed him as an 18-year-old phenom.

THE 1940s

David Wendell Skaugstad was a 17-year-old left handed pitcher from Compton High School in Compton, CA, when he signed with the Cincinnati Redlegs in September 1957. Skaugstad debuted for the Redlegs in relief against the Chicago Cubs on September 25, 1957. He surrendered three hits and three walks but allowed no runs in a four-inning no-decision, finishing the last game of the year at Crosley Field, a 7-5 loss to the Cubs. Skaugstad was the third of three fledgling pitchers to throw that day for Cincinnati.7 along with first-time starter and 20- year-old bonus baby Jay Hook (later the first pitcher to win a game for the expansion 1962 Mets) and 18- year-old Claude Osteen.

Despite his fine initial outing, Dave Skaugstad was to appear in only one more major league game. On September 29, the last day of the 1957 season, the Redlegs were in Milwaukee playing the NL champion Braves. On the day after breaking the NL single season record for attendance, 45,000 hometown fans were treated to a pitching duel between Redlegs starter Jay Hook and Braves starter Bob Buhl, with both throwing no-hitters after five innings. Before the start of the sixth inning Reds manager Birdie Tebbetts remarked, “He’s too young to throw a no hitter,”8 and lifted Hook, replacing him with Dave Skaugstad. Skaugstad retired pinch-hitter Andy Pafko, second-basemen Red Schoendienst in search of his 200th hit of the season, and shortstop Johnny Logan to preserve the no-hitter. In the seventh inning of the still scoreless game, Skaugstad retired future Hall of Famers Eddie Mathews and Hank Aaron, but then walked Wes Covington and allowed the first hit of the game to Brave first baseman Joe Adcock. Skaugstad’s inexperience got the better of him as he walked the next two batters to force in a run. After pitching 1 2/3 innings, he was removed for veteran Hersh Freeman, leaving to a hail of boos from the partisan crowd. Cincinnati rallied to take the lead in the top of the ninth, but eventually lost the game 4-3 in the bottom of the ninth.

Dave Skaugstad enjoyed a minor league career that extended from 1958 through 1965, wrapped around a three-year stint in the Army. A good-hitting pitcher, in 1959 he played first base and outfield between starts for the PCL Seattle Rainiers and lobbied the Redlegs’ organization to be converted into an everyday player. His “conversion” ended after he struck out 18 batters in a game during 1960 for Class D Geneva. Back problems caused Skaugstad to take the next year off, during which he enlisted. Pitching for the V Corps Guardians baseball team in Europe, he developed a forkball and a goal of returning to the majors by 1965. After a strong early season showing with Class AA Knoxville in 1965, Skaugstad was called up by Cincinnati to pitch in an exhibition game with the Chicago White Sox. He warmed up in the bullpen once but never appeared in the game. Sent back to Knoxville, he pitched poorly in the second half of the season and a lingering rotator cuff problem caused him to retire at the ripe old age of 25.

THE 1950s

The first major leaguers born in the 1950s were a pair of 19-year-olds-Californian Lloyd Allen and Connecticut native and future Mets manager Bobby Valentine, both of whom debuted in early September 1969 as late season call-ups (Allen with the California Angels and Valentine for the Dodgers). Allen, the Angels’ first selection in the 1968 amateur draft, was the first of the two to appear in a game, pitching an effective inning of relief in the front half of a doubleheader with the Senators on September 1 in a shutout loss to Joe Coleman. A newspaper account of the game mentions that David and Julie Eisenhower attended the game, the newlywed grandson of former President Dwight Eisenhower and daughter of then President Richard Nixon.9

Allen’s strong showing earned him a start his next time out from manager Lefty Phillips. Allen started the penultimate game of the season for the Angels against the Kansas City Royals on October 1, 1969. In a rain-shortened five-inning game, Allen walked eight batters, including filling the bases by walks twice and lost a 6-0 shutout to Royals’ rookie Bill Butler. This was Butler’s fourth shutout of the year, helping secure for the Royals the best record by an expansion team in the then 100-year history of the major leagues.

Lloyd Allen played for several more seasons, principally as a reliever for the Angels, Rangers, and White Sox. In 1971, he led the Angels with 15 saves, including a game on July 16, 1971, in which he completed the rare combination of both hitting a home run and earning a save. Allen’s career won-lost record was unsightly at 8-25, with 22 saves and a 4.69 ERA. He lost his last 10 decisions between 1972 and 1975, including his final appearance, a 2/3-inning start against the Oakland Athletics in which he allowed a two-run HR to future Hall of Famer Reggie Jackson.

THE 1960s

Tim Conroy was the first player born in the 1960s to reach the majors. Selected by the Oakland Athletics in the first round of the 1978 June amateur draft (the 20th overall pick), Conroy was less than a month out of high school when he was added to manager Jack McKeon’s A’s squad. Just prior to his arrival, owner Charlie Finley claimed that Tim Conroy had “more poise than Catfish Hunter … when I brought [him] up as [a] kid.”10 Conroy joined fellow 18-year-old hurler Mike Morgan on the roster, who had also jumped from high school to the big leagues that same month.11 Prep catcher Brian Milner, a seventh-round draft choice, also jumped from high school to the majors, debuting the same day as Conroy.

Conroy debuted as the starting pitcher in the second game of a doubleheader with the Kansas City Royals on June 23, 1978. In front of the second largest crowd of the year at Royals Stadium, Conroy pitched 3 1/3 innings, allowing only one run and two hits while walking five Royals in a game won by the A’s. The second and final major league appearance for Conroy that year was another start in which he did not fare as well-allowing five runs on only one hit in 1 1/3 innings at home against the Texas Rangers. A first-inning error by Conroy on a Bert Campaneris sacrifice bunt, four walks, and two stolen bases earned him a quick shower but not a loss as Oakland eventually won in 10 innings.

Reassigned to the minors, Tim Conroy toiled for four years before returning to Oakland in 1982. Ultimately, after a lackluster 10-19 career record with Oakland, Conroy was traded to the St. Louis Cardinals in December 1985 along with catcher Mike Heath for 21-game winner Joaquin Andujar. The trade occurred just two months after Andujar’s meltdown in game seven of the 1985 World Series where he charged home plate umpire (and game six “villain”) Don Denkinger following two disputed pitches in an 11-0 loss to Bret Saberhagen and the Kansas City Royals. Andujar’s Series antics made him a pariah in St. Louis, leading to the quick trade for seemingly unequal talent.

THE 1970s

Venezuelan-born Wilson Alvarez, first major leaguer born in the 1970s, bears the distinction of being one of the few major leaguers to play in the Little League World Series, appearing in the 1982 LLWS with the Coquivacoa Little League of Maracaibo. Alvarez debuted for the Texas Rangers on July 24, 1989, appearing as the starting pitcher against the eventual AL East champion Toronto Blue Jays. Called up from Class AA Tulsa to fill in for an injured Charlie Hough, the 19-year-old left hander was rudely welcomed into the fraternity, as many rookie pitchers are-allowing first inning home runs to Tony Fernandez and Fred McGriff facing five batters in all without recording a single out.

Alvarez returned to the Tulsa team and five days later was bundled by the Rangers in a trade with the Chicago White Sox for veteran outfielder Harold Baines. Accompanying him to the Windy City was a young outfielder from the Rangers’ Triple A Oklahoma City roster, Sammy Sosa, who a few weeks earlier had drilled his first major league home run. Alvarez was assigned to a ChiSox minor league affiliate, not to appear in another major league game for two years. As a result, he carries an ERA of infinity for his 1989 major league season.

Alvarez returned to the major leagues with a bang. Called up by the White Sox from Double A Birmingham in the summer of 1991 after posting a 10-6, 1.83 ERA record, Alvarez was immediately given an opportunity to start. On August 11, in his first outing for the ChiSox and only the second game of his major league career, Alvarez tossed a no-hitter against the Baltimore Orioles. Striking out seven Orioles en route to a 7-0 victory, Wilson Alvarez became the most inexperienced major league pitcher to throw a no-hitter since the St. Louis Browns’ Bobo Holloman blanked the Philadelphia A’s in his 1953 major league debut.

Later in his career, Wilson Alvarez earned the distinction of starting the first regular season game for the Tampa Bay Devil Rays on March 31, 1998. More recently with the Los Angeles Dodgers, Alvarez suffered the indignity of serving up the 2004 NLDS clinching home run in the eight inning of game four to St. Louis Cardinal slugger Albert Pujols.

THE 1980s

The preseason rosters for 2001 included quite a few young players born in 1980, including future World Series MVP Josh Beckett, current Indians ace C. C. Sabathia and Dodger shortstop Cesar Izturis. But the very first player born in the 1980s to appear in a major league game was Albert Pujols. The Dominican Republic native was a 13th-round selection by the St. Louis Cardinals in the 1999 amateur draft, turning down the Cards’ initial contract offer, but eventually signing for a $60K bonus in the summer of 1999. Pujols earned league MVP honors for Class A Peoria of the Midwest League in 2000, finishing the year with Class AAA Memphis. Taking advantage of a roster spot made available by a spring training injury to Bobby Bonilla, Pujols was the 2001 opening day left fielder for the Cardinals. He went l-for-3 and was caught stealing in his debut against Mike Hampton and the Colorado Rockies in an 8-0 loss on April 2, 2001. Pujols hit his first major league home run, along with a double and three RBI, on April 6 in the Cardinals first win of the season, against the eventual World Series champion Arizona Diamondbacks.

Albert Pujols went on to earn NL Rookie of the Month honors for May 2001 and was the first Cardinal rookie selected to the All-Star team since Luis Arroyo in 1955. He finished the year batting .329 with 37 HR and 130 RBI, leading the Cardinals to a wild card berth and unanimously winning NL Rookie of the Year honors. Pujols has continued to dominate NL pitching in his four seasons with the Cardinals. He was runner-up to Barry Bonds in the NL 2002 and 2003 MVP voting, leading the NL in 2003 in batting average (.359), hits (212), runs (137), and doubles (51). With another stellar season in 2004, he has joined Joe DiMaggio and Ted Williams as the only players to collect 500 RBI in their first four seasons. Pujols earned the NL 2004 LCS MVP award and, despite his lackluster performance in the 2004 World Series, has emerged as arguably the best young hitter in the game today.

Today there are no major leaguers born in the 1990s, but in four, five, or maybe six years some lucky youngster will be given the opportunity. The tantalizing question is whether his career will follow the course of a John Cavanaugh, ending as soon as it began—or that of an Albert Pujols, challenging the record books with the very real prospect of enshrinement in the Hall of Fame one day.

LARRY DeFILLIPO is a wanna-be Mets statistician masquerading as an aerospace engineer in his newly adopted home of Ashburn, Virginia. This is his first article published by SABR.

Sources

Wood, Allan. Babe Ruth and the 1918 Red Sox. Lincoln, NE: Writer’s Club Press, 2000.

www.baseballlibrary.com

www.baseball-reference.com

www.retrosheet.org

en.wikipedia,org

www.williamsportonline.com

Notes

- Technically speaking, 1901 was the first year of the 20th century, and so Phillip “Lefty” Weinert was the first player born in the 20th century to appear in a major league Born in Philadelphia, PA, on April 4, 1902, Weinert debuted as a relief pitcher with the hometown Phillies on September 24, 1919, not yet 17½ years old. Though not at the same time, he was a teammate of 1900’s firstborn John Cavanaugh, who was also born in southeastern PA. For consistency with the other decades, I’ve elected to explore the career of Cavanaugh rather than Weinert.

- Chicago Tribune, July 9, 1919, 19.

- Several of the Philly players objected to Coombs’ removal and staged a “strike,” sitting in street clothes and getting drunk in the bleachers at Baker Field during the July 8 contest with the Cubs. The apparent ringleader, pitcher Gene Packard, was fined $200 by William Baker and soon released. As detailed in Babe Ruth and the 1918 Red Sox, Packard was implicated by Harry Grabiner, secretary to White Sox owner Charles Comiskey, of fixing the 1918 World Series—won by the Boston Red Sox over the Chicago Cubs, for whom Packard played in 1916 and 1917. AL President Ban Johnson had apparently suspected the 1918 Series was fixed, but neither he nor Commissioner Kennesaw Landis ever launched an official investigation.

- Washington Post, March 16, 1945, 12.

- New York Times, April 16, 1939, p. 34. Harridge’s article also announced the planned June 12 enshrinement of the inaugural “Hall of Fame” members on the 100th anniversary of baseball in Cooperstown, NY.

- New York Times, October 20, 1948, 41.

- Los Angeles Times, September 26,1957, C5.

- Letters from David Skaugstad to the author, November 29 and December 21, 2004.

- Washington Post, September 2, 1969, DI.

- Washington Post, June 18, 1978, D3.

- Morgan’s debut in early June 1978 was an inauspicious one, lasting less than an inning after he tripped and severely sprained his ankle while backing up third base on a hit to the second batter he faced.