Profiles in Plumage: The San Diego Chicken

This article was written by John Racanelli

This article was published in The National Pastime: Pacific Ghosts (San Diego, 2019)

June 29, 1979, was a night unlike any other at San Diego Stadium. Fans were gnarled in a four-mile-long traffic jam and the start of the game was delayed 36 minutes.1 Gaylord Perry was scheduled to face Houston’s Joaquin Andujar that night. But the capacity crowd of 47,022 was not necessarily there to see baseball.2 San Diegans had flocked to the ballpark to watch a man hatch from a gigantic Styrofoam egg in what would become perhaps the greatest promotion in the history of baseball — the “Grand Hatching.” The tale of Ted Giannoulas and his chicken suit is a quintessential study in perseverance, innovation, and, perhaps regrettably, an inexhaustible supply of barnyard puns. The Chicken’s favorite baseball play, for example, is the balk.3 With this in mind, the author has endeavored to avoid laying an egg in the telling of the San Diego Chicken’s story.4

The Young Cluck

Ted Giannoulas was born in London, Ontario, to parents John and Helen, who had immigrated to Canada from Greece. As a child, Ted was a rabid baseball fan and would often listen to ballgames on a transistor radio hidden under his pillow, receiving AM transmissions from as far away as St. Louis, Pittsburgh, New York, and Cincinnati.5 He organized sandlot baseball games and would bribe the best players to join his team with six-packs of soda he would sneak from his parents’ restaurant. Giannoulas dreamed of someday playing shortstop for the Giants, having become a fan of the team — based some 2,500 miles from his home — when San Francisco got off to a hot start in 1962.6

Ted Giannoulas was born in London, Ontario, to parents John and Helen, who had immigrated to Canada from Greece. As a child, Ted was a rabid baseball fan and would often listen to ballgames on a transistor radio hidden under his pillow, receiving AM transmissions from as far away as St. Louis, Pittsburgh, New York, and Cincinnati.5 He organized sandlot baseball games and would bribe the best players to join his team with six-packs of soda he would sneak from his parents’ restaurant. Giannoulas dreamed of someday playing shortstop for the Giants, having become a fan of the team — based some 2,500 miles from his home — when San Francisco got off to a hot start in 1962.6

In 1969, the Giannoulas family moved to San Diego, his father finding the agreeable weather reminiscent of his native Athens. Ted attended Hoover High School, Ted Williams’s alma mater, where Ted was the sports editor for the school newspaper, but not the mascot. He eschewed portraying the Hoover Cardinal, joking with his friends that he was “way too cool” to be a glorified cheerleader.

After graduation, Giannoulas enrolled at San Diego State, where he majored in journalism, aspired to a career in broadcasting, and was a backup goalie for the Aztecs’ club hockey team. In fact, he often ponders whether he would have ever become the Chicken if he’d been the starter.7

KGB Radio and the Rise of the Chicken

Giannoulas becoming the Chicken was mere happenstance. While he was hanging out at San Diego State right before spring break, a man from KGB radio approached a group of students and asked if anyone was interested in passing out eggs at the San Diego Zoo for a radio promotion — a job that was to last two weeks and pay $2 an hour.8 Giannoulas, who was 5’3” and 120 pounds “flopping wet,” was chosen as the one most likely to fit the rented chicken costume.9 He saw the chicken job as a foot in the door for future employment in KGB’s news department.10

Giannoulas attended the Padres home opener on April 9, 1974, dressed in the chicken costume, mainly so he could get in for free.11 KGB told him, “Just be a fan. Buy a beer and a hot dog, cheer on the Padres.”12 So that was what Giannoulas did, along with shaking hands and kissing babies. He left the game early, but not before new Padres owner Ray Kroc grabbed the public address microphone and famously upbraided the team for its “stupid” play.13

Ironically, however, Giannoulas was first mentioned by name in the newspapers as a frog. Still working for KGB’s promotions department in August 1974, he set the world record for go-kart driving at the El Cajon Carting Center while dressed as Tyrone the Frog.14

He continued to appear at San Diego Stadium throughout 1975, and by 1976 other teams had taken notice of the Chicken’s antics. Giannoulas was invited by St. Louis Cardinals trainer Gene Gieselmann to Busch Stadium in August 1976.15 There, he arm-wrestled Keith Hernandez, got an autographed bat from Red Schoendienst and entertained the fans, all while unabashedly rooting for the visiting Padres.16 Capping off his successful year, Giannoulas was awarded the 1976 Sports Performance MVP by the San Diego Evening Tribune, beating out Padres Cy Young Award-winner Randy Jones and Chargers receiver Charlie Joyner.17

Commissioner Bowie Kuhn was scheduled to be in San Diego for the 1977 home opener and called the Padres with an offer to throw out the ceremonial first ball of the season.18 Kuhn was rebuffed — the Padres had already promised the honor to the Chicken.19 After practicing all day at Hoover High School’s baseball field, Giannoulas took the mound on April 12 and threw a strike, but not before he used the rosin bag as deodorant and groomed the mound on all fours, just like Mark “The Bird” Fidrych. On May 28, the Chicken got to perform on the field for the first time while participating in a commercial shoot during the fifth-inning break. With no real plan, Giannoulas decided to wing it: He pantomimed spectacular plays at shortstop and engaged umpire Art Williams — much to his surprise — all to howling approval.20

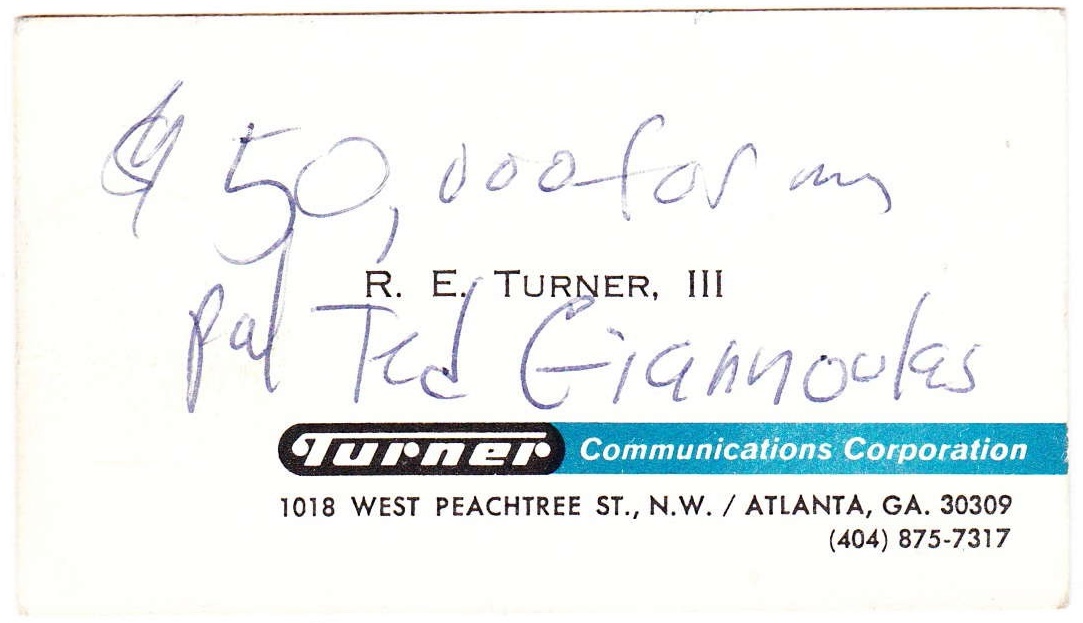

Padres executive Ballard Smith told Giannoulas that Atlanta Braves owner Ted Turner proposed a trade at the 1978 owners meetings that would have sent the Padres a backup catcher in exchange for the Chicken. After he was advised the Chicken was not the Padres’ asset to trade — Giannoulas was still employed by KGB — Turner set out to lure him to Atlanta. While Giannoulas was appearing for a game at Fulton County Stadium in early September 1978, Turner offered him $50,000 (not chicken feed; this is about $191,000 today) to move to Atlanta and give life to a new character. When Giannoulas — who still lived at home — was hesitant, Turner increased the offer to $100,000, threw in a television show, and promised an office next to Hank Aaron!21 After an outpouring of pleas from San Diegans, including Mayor Pete Wilson, Giannoulas ultimately decided to stay in San Diego.22 For his loyalty, KGB agreed to pay Giannoulas $50,000 per year, making him the second-highest paid employee at the station and equaling the yearly salary of Padres hurler Bob Shirley.23 Giannoulas was also granted permission to accept payment for out-of-town appearances as the KGB Chicken.24

During his reign as the KGB Chicken, KGB’s ratings climbed from fifth in San Diego to first, Giannoulas won an Emmy for a KGB commercial, and he was awarded a commendation from the state Legislature for his “comedy contributions to the State of California.” When a regional magazine polled Padres fans, 11 percent said they came to the games just to see the Chicken.25 At the time, Tony Gwynn was a two-sport star at San Diego State. He often went to Padres games “and a lot of times it was to see the Chicken. I loved [Dave] Winfield and Ozzie [Smith] at the end, but you know after a while, it was ‘Hey, the Chicken — what’s the Chicken doing?’”26

Atlanta Braves owner Ted Turner memorialized his initial employment offer to Ted Giannoulas on his business card. (COURTESY OF TED GIANNOULAS)

Cracks Appear

When Giannoulas performed in Seattle on May 4, 1979, for a nationally televised NBA playoff game, he did so without displaying the KGB logo, which ruffled the feathers of KGB management. Giannoulas was fired and made the defendant in a $250,000 breach of contract lawsuit filed by KGB.27 At a May 23 hearing, Giannoulas was stripped of the chicken suit and barred from appearing in the costume in San Diego and the surrounding counties.28

Giannoulas, however, was ready for a fight. With the help of his mother and sister, Giannoulas designed a new chicken costume, complete with his very own logo.29 He struck a deal with the Padres and held a press conference at the ballpark on June 25 from inside the giant Styrofoam egg, forcing reporters to put their ears and microphones up to the shell. Giannoulas invited all to witness the “Grand Hatching” ceremony planned for the June 29 game against the visiting Astros.30

Throughout that week, the giant egg was on display in the right-field pavilion — only to disappear the night before the Grand Hatching was set to take place. Although KGB was an immediate suspect, the station was cleared once the actual thieves sobered up and contacted the local news to broker a deal for the return of the egg. Their demands included that no charges be filed and that they be given twelve tickets to the Grand Hatching game and all the beer they could drink; Giannoulas had little choice but talked them down to four tickets and $20 for beer.31

Prior to the start of that June 29 game, the capacity crowd chanted, “We want the chicken!” as the outfield gates opened and the egg — perched precariously atop an armored truck and with a California Highway Patrol motorcycle escort — made its way to third base.32 After being placed gently on the ground, the egg began to roll around and came to rest as Giannoulas burst triumphantly from the shell, revealing the San Diego Chicken to the world.33 Shrewdly, Giannoulas had negotiated a deal with the Padres in which he would be compensated a portion of each ticket sold above average attendance, pocketing in excess of $40,000 for the Grand Hatching spectacle. That money was applied directly to his mounting legal fees, as he continued to fight the lawsuit filed by KGB and separate contempt charges KGB brought against Giannoulas for continuing to make appearances.34

Chicken Suits

In 1980, Giannoulas scored a pair of significant legal victories. On April 16, the San Diego Superior Court dismissed the contempt charges brought by KGB following a two-day hearing that culminated in the San Diego Chicken and KGB Chicken standing side-by-side in the courtroom. Judge Raul Rosario held that the costumes were not “substantially similar,” which made Giannoulas a “free bird.”35

Shortly thereafter, the appeal of KGB’s suit for breach of his employment contract was decided in favor of Giannoulas.36 Justice Gerald Brown proclaimed, “Silly though the issues appear at first glance, the underlying principles are serious.”37 The reviewing court held that Giannoulas’s post-employment performances in a chicken costume were neither competitive nor unfair because he did not sport the station logo or otherwise imply that he represented KGB radio.38 Further, the chicken costume designed by Giannoulas and his family was not “substantially similar” and the court could not ban him from appearing in “any chicken suit whatsoever.” 39 The injunction entered by the lower court prohibiting him from performing in a chicken suit in San Diego and adjacent counties had improperly restricted Giannoulas’s “rights to earn a living and to express himself as an artist.”40

Relying on a precedential case involving Bela Lugosi’s movie portrayal of Dracula, the court found, “masked or not, both Lugosi and Giannoulas have made certain roles their own, by a combination of mannerisms, gestures, body language, and other behavior adding up in each case to a unique character.”41 The court also found unpersuasive KGB’s claim that it made no difference who wore the costume, “if that were so, why did KGB pay Giannoulas some $50,000 a year to wear it?”42 Ultimately, the court found in favor of Giannoulas on all counts, except that he was prohibited from making any further appearances as the KGB Chicken.43

Free Bird

Once free of the KGB litigation, Giannoulas was truly able to spread his wings, making upwards of 250 appearances per year all over the country, and eventually the world. By his count, Giannoulas has performed live in front of millions of fans at over 8,500 games.

Once free of the KGB litigation, Giannoulas was truly able to spread his wings, making upwards of 250 appearances per year all over the country, and eventually the world. By his count, Giannoulas has performed live in front of millions of fans at over 8,500 games.

He starred on The Baseball Bunch, a television program hosted by Johnny Bench.44 Bench knew Giannoulas well from the Big Red Machine days, when the two often conspired to pull pranks on Pete Rose.45 In fact, Bench has warmly referred to the Chicken as his “idol.”46 Giannoulas’s favorite memory of The Baseball Bunch was when Ted Williams appeared on the show to do some hitting demonstrations, bringing together Hoover High School’s most famous graduates. On the big screen, the Chicken had a cameo role in the cult classic Attack of the Killer Tomatoes.47

But the Chicken’s shtick is not for everyone. Lou Piniella once threw his glove at the Chicken after he put a “hex” on Yankees pitcher Ron Guidry during a game against Seattle at the Kingdome in 1979.48 “We win the pennant, and they want to make the Chicken bigger than the team,” groused Padres general manager Jack McKeon after the Padres qualified for the 1984 World Series. “Marketing people thought he was the reason we were putting people in the ballpark. . . . Do your act and get the hell off of the field.”49

Giannoulas has also had to defend himself in court on several occasions. Pitcher Don Schulze sued him for $2 million, claiming the Chicken separated his shoulder during an exhibition game in 1981 when Schulze was a member of the Quad Cities Cubs.50 Giannoulas was exonerated after the jury watched a video of the incident.51 Giannoulas also prevailed in a lawsuit brought by the intellectual property owners of the Barney character in 1999. They were offended by a skit in which the Chicken would “flip, slap, tackle, trample, and generally assault” a Barney lookalike called “Duffy the Dragon.”52 The court held that the performance was a parody and “denying parodists the opportunity to poke fun at symbols and names which have become woven into the fabric of our daily life would constitute a serious curtailment of a protected form of expression.”53 More recently, Giannoulas successfully fended off a lawsuit filed by a fan hit by a foul ball at a 2004 Dayton Dragons game who claimed she was distracted by the Chicken.54

Feathers in His Cap

Proving that good things come in small peck-ages, the San Diego Chicken remains an innovative and enduring figure in sports entertainment. Giannoulas was the first mascot to talk and make noises as part of his act and, through his routines, introduced pre-recorded music to the ballpark.55 He broke new ground with his own card in the 1982 Donruss baseball set — the first fan to be featured in a nationally distributed issue.56 He was named one of the 100 Most Powerful Sports Figures of the 20th Century by The Sporting News, right behind Wayne Gretzky.57 The Chicken was even honored with his own bobblehead night at Qualcomm Stadium on September 26, 2003.58

Giannoulas was an inaugural inductee into the Mascot Hall of Fame in 2005 and was inducted into Baseball Reliquary’s Shrine of Eternals on July 16, 2011.59 His San Diego Chicken costume is featured prominently at the National Baseball Museum in Cooperstown and another Chicken head is displayed at the Gerald Ford Presidential Museum in Grand Rapids, Michigan.60 In 2018, an authenticated Chicken head sold for nearly $10,000 at auction.61

Giannoulas is “semiretired” now but plans to perform as long as he is physically able, including appearances with the Padres in 2019 to help commemorate the team’s 50th anniversary.62 And perhaps the man in the chicken suit said it best: “There’s no way, really, of knowing what the future holds, but I hope there are many more laughs ahead for us.”63

JOHN RACANELLI is a Chicago lawyer with an insatiable interest in baseball-related litigation. When not rooting for his beloved Cubs (or working), he is probably reading a baseball book or blog, planning his next baseball trip, or enjoying downtime with his wife and family. He is probably the world’s foremost photographer of triple peanuts found at ballgames and likes to think he has one of the most complete collections of vintage handheld electronic baseball games known to exist. John is a member of the Emil Rothe (Chicago) Chapter of SABR.

Photo credits

Courtesy of Ted Giannoulas.

Notes

1 “Chicken Man Hatched Again,” Austin American-Statesman, June 30, 1979.

2 The Los Angeles Times, June 30, 1979.

3 Ted Giannoulas, telephone interview, January 14, 2019.

4 Giannoulas is known as the San Diego Chicken, the Famous Chicken and the Famous San Diego Chicken. He uses these interchangeably, depending on whether he is performing somewhere fans might not take kindly to a visiting or rival mascot.

5 Giannoulas, telephone interview. He fondly recalled listening to Harry Caray with the Cardinals, Bob Prince with the Pirates, Lindsay Nelson with the Mets, and Joe Nuxhall with the Cincinnati Reds.

6 “The Giants’ fowl friend,” King Thompson, San Francisco Examiner, April 22, 1982.

7 Giannoulas, telephone interview.

8 Giannoulas.

9 Ron Hutcherson, “The Chick Col. Sanders Forgot,” Press Democrat (Santa Rosa, CA), July 31, 1977.

10 Ted Giannoulas, telephone interview, January 14, 2019.

11 Giannoulas.

12 KGB Chicken (Ted Giannoulas), From Scratch (San Diego: Joyce Press, 1978), 7.

13 Phil Collier, “Padre Kroc Eats Humble Pie After ‘Stupid’ Slur,” The Sporting News, April 27, 1974.

14 “Young Women Set Nonstop Go-Cart Mark,” Progress Bulletin (Pomona, CA), August 21, 1974. (Giannoulas drove for 75 hours and 26 minutes.)

15 KGB Chicken, From Scratch, 61.

16 From Scratch.

17 “Chicken-Man MVP,” Chicago Tribune, January 1, 1977.

18 Mike Lopresti, “In San Diego, the ‘Chicken Game’ is Baseball,” Palladium-Item (Richmond, IN), July 16, 1978.

19 Lopresti.

20 KGB Chicken, From Scratch, 42–3, 46–7.

21 Giannoulas, telephone interview. Giannoulas had also separately been offered a three-year, $225,000 pact by KVI and the Seattle Mariners)

22 “$100,000 Chicken Feed to Ted Turner,” Atlanta Constitution, September 14, 1978. (California Governor Pete Wilson later hosted “Chicken Day” and honored Giannoulas for taking “a Sherman-like stand on an attempted coup bordering on chicken-snatching on the part of Atlanta.”) “‘Hysterical Landmark’ Becoming Free Agent?” Tampa Tribune, May 11, 1979.

23 Giannoulas, telephone interview; “Bob Shirley,” Baseball Reference, https://www.baseball-reference.com/players/s/shirlbo01.shtml.

24 “$50,000 Chicken is Fired,” Press Democrat, May 9, 1979.

25 Patricia Lee Murphy, “Looking for Some Chicken Delight? Just Order Up Ted Giannoulas, Who’s Sure Not to Lay An Egg,” People, September 25, 1978.

26 “Chicken Bids Goodbye to Where it All Began,” New York Times, September 28, 2003.

27 “$50,000 Chicken is Fired.”

28 “Mascot is Stripped of Chicken Suit,” Minneapolis Star, May 30, 1979.

29 “He’ll Still Roost with San Diego Team,” Lansing (Michigan) State Journal, June 24, 1979. (If you look closely at the Chicken’s logo, you will see that the middle of the “C” is cleverly shaped like an egg.)

30 “‘The Chicken’ Plots Return,” Tulare (California) Advance-Register, June 26, 1979.

31 Giannoulas, telephone interview; Steve Dolan, “Giannoulas Can’t Egg the Astros Into a Defeat, 4-1”, Los Angeles Times, 1:III.

32 “It’s a Bird/The Chicken Re-hatches,” San Bernardino County Sun, June 30, 1979.

33 The Famous Chicken, “The Grand Hatching” video, YouTube, https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=IVrDjDyHJwY=.

34 Giannoulas, telephone interview.

35 “‘I’m a Free Bird,’ Giannoulas Crows,” Los Angeles Times, April 17, 1980.

36 KGB, Inc. v. Giannoulas, 104 Cal.App.3d 844 (1980).

37 KGB, Inc. v. Giannoulas at 846.

38 KGB, Inc. v. Giannoulas at 850.

39 KGB, Inc. v. Giannoulas at 847. (The injunction had forbidden Giannoulas from appearing anywhere in the KGB Chicken costume or any “substantially similar” costume; in any “chicken ensemble or suit whatsoever” in San Diego County or an adjacent county; and, in a chicken suit at any sports or public event in which a team from San Diego County appears.)

40 KGB, Inc. v. Giannoulas.

41 KGB, Inc. v. Giannoulas at 855.

42 KGB, Inc. v. Giannoulas.

43 KGB, Inc. v. Giannoulas at 853.

44 Giannoulas, telephone interview.

45 Bill Francis, “San Diego Chicken Lands at Doubleday Field,” Freeman’s Journal, July 30, 1999.

46 Dan Barriero, “Ted Giannoulas Winds Up Making More Than Just Chicken Feed,” Los Angeles Times, August 27, 1983.

47 Giannoulas, telephone interview.

48 “Mariners 5, Yankees 1” Herald-Palladium (St. Joseph, MI), July 11, 1979.

49 “Mickey Mouse, Ronald McDonald don’t make cut,” ESPN.com, August 16, 2005. http://www.espn.com/espn/news/story?id=2135976.

50 Mandy Mueller, “Pitcher Says ‘Chicken’ Tackled Him,” UPI, October 16, 1985. https://www.upi.com/Archives/1985/10/16/Pitcher-says-Chicken-tackled-him/5712498283200/.

51 Mueller; Schulze v. Chicken’s Co., 802 F.2d 464 (Table) (8th Cir., 1986).

52 Lyons Partnership v. Giannoulas, 179 F.3d 384 (C.A.5 (Tex.), 1999); see also https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=5UmgRjgeRpM.

53 Lyons Partnership v. Giannoulas, 14 F.Supp.2d 947, 953 (N.D. Tex., 1998).

54 Harting v. Dayton Dragons Professional, 870 N.E.2d 766 (Ohio App., 2007). (Giannoulas did lose a personal injury case involving a Chicago Bulls cheerleader. Smyth v. Giannoulas, 1991L019113, Cook County, Illinois, May 1996.)

55 Giannoulas, telephone interview.

56 Associated Press, “Now That He’s a Card, Will He Lay an Egg?,” San Francisco Examiner, December 23, 1981.

57 “100 Most Powerful Sports Figures of the 20th Century,” The Sporting News, December 20, 1999.

58 Associated Press, “Chicken Bids Goodbye to Where it all Began,” New York Times, September 28, 2003.

59 “Baseball Reliquary to hold ‘Shrine of the Eternals’ induction,” The Sun (San Bernardino), July 13, 2011. (To be eligible for induction into the Mascot Hall of Fame, a mascot must have been in existence at least 10 years; have a major impact on its sport, industry and community; and have a performance that is consistently memorable and groundbreaking.)

60 Hall of Fame clipping file; Giannoulas, telephone interview.

61 LOT #852: San Diego Chicken Mascot Head, GoldinAuctions.com, https://goldinauctions.com/San_Diego_Chicken_Mascot_Head-LOT39293.aspx, accessed February 11, 2019.

62 Giannoulas, telephone interview.

63 KGB Chicken, From Scratch, p. 94.