Punching Above Its Weight: The Quebec Provincial League

This article was written by Christian Trudeau

This article was published in Our Game, Too: Influential Figures and Milestones in Canadian Baseball (2022)

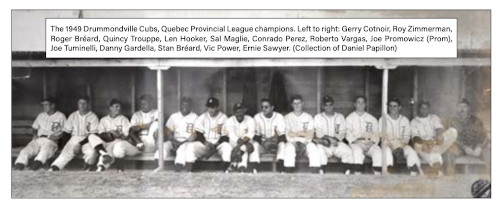

The 1949 Drummondville Cubs, Quebec Provincial League champions. Left to right: Gerry Cotnoir, Roy Zimmerman, Roger Bréard, Quincy Trouppe, Len Hooker, Sal Maglie, Conrado Perez, Roberto Vargas, Joe Promowicz (Prom), Joe luminelli, Danny Gardella, Stan Bréard, Vic Power, Ernie Sawyer. (Collection of Daniel Papillon)

George Gmelch, then playing for the Drummondville Royals, recalled a 1968 incident after a bad call by an umpire: “Some Drummondville fans went to the parking lot and let the air out of the tires of the umpire’s car. When the umps came out, some fans were still there. They cursed the umps and beat on the hood of their car. … It was strange seeing fans get that upset over a fairly unimportant game…I wondered why the fans cared more about the outcome of the game than we did.”1

Intensity was a feature of various incarnations of the Quebec Provincial League in the 1920-70 period, the product of a mix of civic pride and heavy gambling. It led to many such ugly incidents as the one described above, mostly involving umpires. However, it also allowed the league to punch far above its weight, with a level of play significantly above that of leagues with comparable population bases. This intense desire to win, fueled by the rivalries among the cities in the geographically compact league, meant that the teams were always on the lookout for the player who would give them the edge. At various times in its existence, the Provincial League raided New England colleges, encouraged players in neighboring leagues to jump their contracts, opened its doors and its checkbooks for Mexican League jumpers banned by the major leagues, and provided opportunity to Negro League veterans or Latin American youngsters.

Unsurprisingly, the league’s relationship with Organized Baseball was rocky, as it gained and lost official sanction. This passion led to incredible highs – the St. Louis Cardinals were outbid by Drummondville for Sal Maglie’s services – but also to inevitable lows. Passion and reason do not mix well, and huge amounts of money were burned in the process. Baseball fans, at least those gambling in moderation, came out ahead as they were able to witness players who should have been playing at a higher level elsewhere.

The first serious attempt to organize a baseball league in Quebec that rose above the level of semipro came during the early 1920s, as Montréal had been without a professional league after the Royals’ departure from the International League after the 1917 season. Organized and presided over by Joe Page,2 the Eastern Canada League was a four-team Class-B league that operated in 1922-23. In its original season, it had teams in Montréal, Trois-Rivières, and Ottawa.3 The next year, Quebec City was added to the league, while the Ottawa team, struggling to find a suitable park, played all but three home games in Montréal. With Trois-Rivières limping to the finish line in 1923 and quitting for 1924, the league responded by expanding, adding teams in Rutland and Montpelier, Vermont, and reorganizing the Ottawa team, creating the Quebec-Ontario-Vermont league. Unsurprisingly, travel expenses killed the two American teams in midseason, and the league itself at the end of the 1924 season. The league provided a decent level of play, as Del Bissonette, Fred Frankhouse, and Bill Hunnefield, for example, graduated to decent major-league careers. The league is however best remembered for having hosted African American Charlie Culver for six games in 1922,4 and for incessant fights between players, umpires, and fans.5

Following the demise of Page’s league, more local leagues emerged, and it wasn’t until 1936 that a league with a schedule of more than a dozen games was established. This new Provincial League,6 outside of the structure of Organized Baseball, had teams in Montréal, Drummondville, Granby, Sorel, and Sherbrooke, as well as the Black Panthers, a travel team of African American players. The addition of Sherbrooke, then the fifth largest city in Quebec, was a major boost to the league. Located near the US border, it had until then played almost exclusively in leagues with teams in Vermont and New Hampshire.

Pushed by a desire to get an edge on its rivals, Granby added to its roster African Americans Fred Wilson in 1935 and Ormond Sampson in 1936. The league quickly rose from a local circuit to one of the top leagues outside of Organized Baseball; by 1939 it was playing a 72-game schedule, and had moved out of Montréal7 to the east, adding solid franchises in Quebec City, Trois-Rivières, and St. Hyacinthe. The Black Panthers struggled in 1937 and were replaced thereafter, no longer fitting with the league’s new and loftier ambitions. By 1939, state-of-the-art twin ballparks had been built in Trois-Rivières and Quebec City, with both of them still in use today. Granby and Sherbrooke also were equipped for night baseball. The league was compact, allowing for travel by car and for the famous home-and-home doubleheaders played each Sunday, a practice that continued throughout the existence of the league.

On the field, the league quickly replaced New England college players with veteran minor leaguers, raiding the nearby Canadian-American and Cape Breton Colliery Leagues. Two players stood out in 1938: Pete Gray with Trois-Rivières and Paul Calvert with Sherbrooke. Trois-Rivières signed Gray sight-unseen, and were shocked to see when he showed up that he had only one arm. He was given a chance and was an immediate sensation, attracting large crowds throughout the league. Gray, an outfielder, would famously play with the St. Louis Browns in 1945.8 Calvert, a Montréal native, became arguably the best prospect ever to come out of Quebec. Armed with a blazing fastball, he rose to fame in 1938, leading the league in strikeouts before refusing an offer from the Yankees, pitching a few games for the Royals, and obtaining a tryout with the New York Giants. Arm issues robbed Calvert of his fastball the following offseason, although he still went on to pitch in 109 major-league games. In 1939 Trois-Rivières opened its checkbook to sign accomplished minor-league stars Dutch Prather, Harlin Pool, Moose Clabaugh, and By Speece. While it was expected that Trois-Rivières had thereby bought the championship, the team barely edged Quebec City for the pennant, before bowing to the same team in the playoff finals. Led by manager Del Bissonette and local star Roland Gladu, Quebec City overcame the loss of three of its pitchers just before the playoffs started.

Being outside Organized Baseball, the teams had little recourse against players who bailed on their contracts; almost all teams were affected by this problem or by players holding out for more money.9 This inability to enforce contracts, combined with out-of-control expenses resulting in alleged financial losses of $50,000 led the league to seek admission into Organized Baseball in 1940.

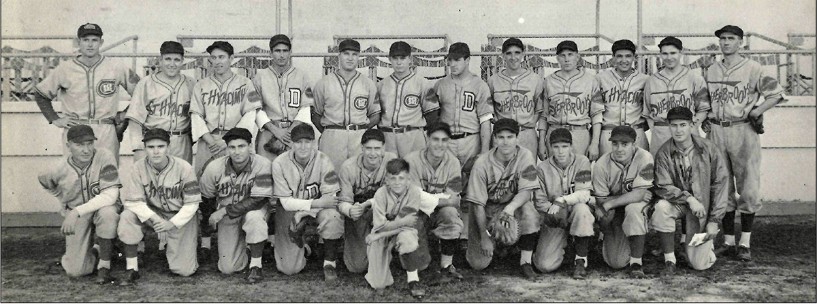

Quebec Provincial League All-Star Game of July 19, 1939. Representatives of Sherbrooke, St. Hyacinthe, Drummondville and Granby. Top Row: Harry Winston, Ted Veach, Ward Sheldon, Art O’Donnell, Vince Barton, Howard Moss, Jim Castiglia, Ray Coté, Keith Drisko, Mike Pociask, Leo Marion, Larry Fisher. Bottom Row: Glenn Larsen, Bob Swan, Joe Cicero, Jerry Levey, Tom Hammond, John Ayvazian, Chris Shearer, John Huxtable, Fletcher Heath, Jim Irving. (Collection of Alexandre Pratt)

Discussions with the National Association of Professional Baseball Leagues continued for most of the offseason, in part because of the hostility of the Montréal Royals. It wasn’t until February that the league was admitted into Organized Baseball, as a Class-B league. The Sorel team would not make the jump. It had made enemies both within and outside the league by signing Bill Powley from Ottawa of the Canadian-American League after rosters had been set for the 1939 playoffs, and then having him use the name of a different player.11 It is not clear whether Sorel refused to play by the rules of Organized Baseball, or whether the club was not invited back by the league. Knowing that Drummondville was its weak link, the league explored many different replacement options, but was constrained by the proximity of existing teams, with potential teams in Hull (now Gatineau) and Lachine (on the island of Montréal) respectively blocked by the Ottawa and Montréal clubs. Unwilling to go on with an uneven number of teams, the league confirmed Drummondville as the sixth team in mid-March.

Drummondville’s return was so late in being announced that the league had already allowed other teams to poach the Drummondville 1939 roster (as well as that of Sorel). The team was terrible, and with attendance further affected by a major strike in a local textile mill, Drummondville folded in early July. At the end of the month, with payroll due and about 1,000 soldiers about to leave town for training, Sherbrooke followed. The remaining four teams continued for a final month of regular-season play, with all of them moving to the postseason. Predictably, fans had a hard time feeling engaged, especially with the unending stream of bad news coming from Europe, as Germany took control of most of Western Europe. Bad weather also played a part. St. Hyacinthe, which had won the pennant, saw big playoff games postponed over Labor Day weekend. Unable to sustain more financial losses, it forfeited its semifinal series to Trois-Rivières, which went on to edge Granby in the finals.

League President Jean Barette resigned after the season, loudly questioning the business acumen of French-Canadians in the process.12 Attempts were made to continue for 1941, but when teams willing to round out the league could not be found, Quebec City and Trois-Rivières jumped to the Canadian-American League, with Quebec City inheriting the rights to Granby players, and Trois-Rivières to the St. Hyacinthe roster.

With the war raging, only low-level local leagues continued their activities, and even the Canadian-American League suspended play after the 1942 season. In 1946, with renewed optimism Quebec City and Trois-Rivières returned to the Can-Am League, while Granby and Sherbrooke joined the Class-C Border League. That was the season in which Jackie Robinson debuted in Montréal, and soon Trois-Rivières and Sherbrooke joined the very short list of integrated teams. As a farm club of the Brooklyn Dodgers, Trois-Rivières welcomed Roy Partlow and Johnny Wright, while Sherbrooke signed Manny McIntyre, an Atlantic Canada two-sport star known primarily for his hockey skills. On the field and in the ledger books, the Border League experience was a failure, with Sherbrooke folding in August and Granby opting out of the league after the season.

In 1947, Sherbrooke and Granby returned to a revamped Provincial League, in which they joined old rivals Drummondville and St. Hyacinthe, along with newcomers St. Jean and Farnham.13 The league started as a typical semipro league, one that could give a chance to a talented but raw player like NHL legend Maurice Richard, who played for Drummondville. But a number of factors quickly contributed to pushing the level of play to unprecedented heights over the next few seasons.

First, local players who had starred in the 1938-40 Provincial League were able to advance their careers during the war. Roland Gladu and Jean-Pierre Roy (who debuted with Trois-Rivières in 1940) both starred with the Montréal Royals and reached the majors during the war. They were joined there by Stan Bréard, too young to have played in the Provincial League previously. Paul Martin, hard-hitting outfielder for Trois-Rivières, didn’t reach the majors but played in the high minors. The network of contacts they had collected, including those in the Cuban winter leagues, would soon come in handy.

Second, returning servicemen provided a sudden surplus of skilled players. Taking advantage of this situation, millionaire Jorge Pasquel offered high salaries to attract major-league players to his Mexican League. Facing a five-year suspension from Organized Baseball, only about 18 players ended up signing, including Gladu. The jumpers were viewed as toxic, and some others, like Roy, Bréard, and Paul Calvert, were suspended for playing with them in the offseason in Cuban winter leagues.

Third, the United States League, and its Pittsburgh Crawfords in particular, had adopted Quebec as a second home in 1945 and 1946, playing many league games in the province. As the league collapsed after the 1946 season, Farnham signed four of its players, although none of them stars. By 1948, with integration decimating the Negro Leagues, Farnham was able to recruit Joe Atkins and brothers Dave and Willie Pope. Nap Gulley, Clarence Bruce, Tom Parker, Buddy Armour, and Len Hooker followed the next year.

Jean-Pierre Roy was the first local star to come back to the Provincial League in 1947, winning 12 games for St. Jean, the eventual champion. Gladu and Bréard returned to Mexico but as their promised money became tougher to obtain, they went looking for new options for 1948. Gladu signed as manager for Sherbrooke, and Paul Martin with St. Hyacinthe, while Roy returned to St. Jean. The result was a scramble for the freely available talent, as Provincial League owners convinced themselves to pay ever-increasing salaries.

Roy brought to St. Jean jumper Bobby Estalella, who had hit .298 and .299 for the Philadelphia As in 1944 and 1945, and Negro League stars Buzz Clarkson and Terris McDuffie, who had also played in Mexico. Estalella (.374-24-95) and Clarkson (.408-31-75) terrorized Provincial League pitchers all season, while Roy and McDuffie each won 19 games. In Sherbrooke, Gladu built a team of Latin American stars, starting with the Cuban Adrian Zabala, who had pitched with the New York Giants in 1945. He led the pitching staff with 18 wins, providing Sherbrooke with a great one-two punch with Paul Calvert, who went 11-1. On offense, Cuban Claro Duany (.365-27-90) and Puerto Rican Francisco “Pancho” Coimbre (.312-8-66) helped Gladu (.368-11-78) lead the team to the pennant. In the 1948 playoff finals, they met Paul Martin’s St. Hyacinthe team. Martin (.356-16-74) did not have the same level of contacts as did Roy and Gladu, but he brought in two veteran hitters he had met in the Southern Association, Gene Nance (.335-14-91) and Connie Creeden (.430-8-71). The best-of-nine series went to the limit and was decided in a see-saw game that, in keeping with the character of the league, included a brawl involving players, umpires, and part of the crowd. Cuban second baseman Jorge Torres’ walk-off single gave Sherbrooke a 10-9 win.

Drummondville was a nonfactor in 1948, but signed Stan Bréard late in the season. Bréard brought with him outfielder Danny Gardella, one of the biggest names among the jumpers, who had hit 18 home runs for the 1945 New York Giants. If it was too late to change tides for 1948, it was a sign of what was to come for 1949.

With the Mexican League jumpers fighting Organized Baseball in court and running out of options – they were reduced to barnstorming and taking odd jobs – most of them accepted offers from the Provincial League. Drummondville named Bréard manager, brought back Gardella, and added pitchers Sal Maglie (only five majorleague wins to that point, but with 114 left in his arm) and Max Lanier (who had been 40-21 with a 2.22 ERA with the Cardinals from 1943 to 1946), as well as first baseman Roy Zimmerman, who had hit 32 home runs for Newark and five more with the Giants in 1945. Defending champion Sherbrooke countered with pitchers Fred Martin (briefly with the 1946 Cardinals) and Harry Feldman (23 wins for the ’44-45 Giants) joining Zabala. St. Jean named catcher Red Hayworth (146 games with the Browns in 1944-45) as manager, replacing the reinstated Jean-Pierre Roy. Hayworth added pitcher Alex Carrasquel (50 wins over seven seasons with the Washington Senators) and second baseman Lou Klein, who had received down-ballot MVP votes as a rookie with the 1943 Cardinals before the war derailed his career.

Bréard also brought to Drummondville two top prospects from Puerto Rico, outfielder Vic Power and pitcher Roberto Vargas, and added veteran Negro League catcher Quincy Trouppe, whom he had met in the winter leagues. Gladu had most of his team back in Sherbrooke, but had added Silvio Garcia, one of the top Cuban players, who had been a candidate to break the color barrier a few years before. St. Jean started the season with three star Negro Leaguers in its rotation, with Chet Brewer (who had been a member of the legendary Kansas City Monarchs) and John “Neck” Stanley (a mainstay for the New York Black Yankees) joining Terris McDuffie. In the outfield, Quincy Barbee replaced Buzz Clarkson. Granby stuck mostly to its strategy of rostering veteran minor leaguers, although it added Tex Shirley, a regular rotation member for the St. Louis Browns in 1945-46. St. Hyacinthe followed the same strategy, its big acquisitions being Walter Brown (who had spent the 1947 season in the Browns’ bullpen), and shortstop Charley Brewster (who had played for four major-league teams from 1943-46, mostly with the Phillies).

As playing with the jumpers could result in suspension, some players used an alias to play in the Provincial League. Ebba St. Claire’s experience is typical. Convinced that he had no future in the Pirates organization, the catcher signed with Sherbrooke, but played as Eddie Thomas. Sherbrooke newspapers revealed St. Claires use of an alias, and provided great details on his minor-league stops, making it easy, at least with today’s tools, to identify St. Claire.14 Given the intense competition between teams, it was not unusual for a newspaper to reveal the identity of a rival team’s hidden player.

Not surprisingly, the league attracted a lot of attention. On June 1, The Sporting News ran a nearly full-page article on the league, stating that Lanier would be paid $10,000 for the season. Drummondville team owners came up with $6,000, with the rest coming from the local business community to ensure that he would not sign with a rival. League President Albert Molini claimed he was aware that the bonanza wouldn’t last forever, and that the league would be seeking entry into Organized Baseball in the next year or two.15 Not shying away from the publicity, Molini later declared that any of his teams could easily defeat International League teams. He also said that teams had an $8,000 to $10,000 monthly payroll, with stars averaging $6,000 to $7,000 for the season.16 Molini also claimed an average of 2,500 fans per game, a number in line with the reported attendances, which rarely dropped below 1,000 and peaked at over 4,000, above capacity.

On the morning of June 6, 1949, as Drummondville sat comfortably at the top of the standings with a 16-3 record, the bubble burst. News that Commissioner Happy Chandler had reinstated the jumpers without condition struck the Provincial League. Jumpers would simply need to write to the commissioner to obtain automatic reinstatement, before obtaining a 30-day grace period during which they could not be released or reassigned to the minors. Molini was initially defiant: “I believe this is the best thing that could have happened. Those that want to leave now can, but I doubt there will be many. Most are satisfied with their lot, and their teams are having great seasons.” While players vowed not to abandon their lawsuits, they listened to offers. Lou Klein (St. Jean) was the first to leave, on June 13, pinch-hitting for the Cardinals three days later. Lanier (8-1 in Drummondville) bargained for three weeks before joining Klein in St. Louis. Soon afterward, Alex Carrasquel returned to the White Sox, while Sherbrooke lost Adrian Zabala (Giants), Fred Martin (Cardinals), and Harry Feldman (San Francisco in the PCL).

If some left in a hurry, others lingered. Zabala, who had spent a year and a half in Sherbrooke, agreed to a going-away start, which turned out to be his best of the season, a 10-inning two-hitter to beat Drummondville 1-0. Others with a limited future in Organized Baseball gladly stayed in Quebec. Sal Maglie was not in this situation. He drew interest from the New York Giants but eventually decided to stay in Drummondville, where he was rumored to have received $15,000 for the season, in addition to a furnished house.17

Drummondville, which had a record of 27-10 when Lanier left, cooled down considerably, but still won the 1949 pennant easily with a 63-34 record, led by Maglie (18-9), Gardella (.28315-59), Zimmerman (.247-22-79), and Power (.345-9-54). The club also bought Tex Shirley (13-3) from Granby for the stretch run. Granby had a surprising second-place finish, led by New Brunswick native Bud Kimball (.314-21-88), but without Shirley, they bowed in the first round to Farnham. Defending champion Sherbrooke had plenty of offense in Gladu (.305-19-81), Duany (.290-22-99), and Garcia (.315-4-76), but after they lost their three jumpers, their pitching staff could not keep up and they were eliminated by St. Jean.18

St. Jean had lost Carrasquel and Negro League stars Chet Brewer and John Stanley during the 1949 season, but was led by McDuffie (12-10) and minor-league veteran Leonard Bobeck (15-10) on the mound, and Barbee (.342-26-86) at the plate. It was not enough against the red-hot Farnham team, which eliminated St. Jean in seven games. Meanwhile, Drummondville needed the maximum nine games to dispatch sixth-place St. Hyacinthe in the other semifinal.

Farnham had finished only in fifth place in the regular season, but had a talented team led by former Negro Leaguers Buddy Armour (.348-8-67), Dave Pope (.293-22-87), Joe Atkins (.253-21-71), and Willie Pope (12-10), as well as veteran minor leaguer Vern Thoele (.305-3-27). For the second series in a row, Drummondville needed the full length of the best-of-nine series. In the ultimate game, Armour homered off Maglie, and Willie Pope kept Drummondville off the Scoreboard for six innings before imploding in the seventh, as the Cubs won 5-1. Maglie struck out 10, winning his third game of the finals. Drummondville ended up champions as expected, but the difficult path it took to get there raised suspicions of game fixing. Molini did not silence these rumors when he decried in The Sporting News the report that $20,000 had been gambled on a semifinal game involving Maglie.19 We can assume at least as much was gambled on the final game.

As the season wrapped up, attention turned toward joining Organized Baseball. The league argued that its high caliber of play warranted Class-B status. Given that the combined population of its cities was less than 250,000, the league was granted Class-C status. The payroll in a Class-C league was a more manageable $3,400 per month.20

While the jumpers were gone, Provincial League teams still were trying hard to win. With no team being affiliated, rosters were filled with veterans, including many who had starred in 1949. Sherbrooke, still managed by Gladu, was the dominant team in 1950 and 1951, losing in the last game of the 1950 finals and winning it all the next year. Silvio Garcia was the star player, winning the Triple Crown in 1950 (.365-21-116). His Cuban compatriot Claro Duany skipped the 1950 season but came back to hit .337-23-84 in 1951. Gladu also added veteran Negro League pitchers Ray Brown and Max Manning. Manning spent only a few weeks in Sherbrooke, but Brown married a local woman and spent many years in Quebec. Brown, who had been the star pitcher of the Homestead Grays, was elected to Cooperstown in 2006. The St. Jean team that stopped them in 1950 was built around young Puerto Ricans Carlos Bernier (.335-15-39) and Ruben Gomez (14-4) and Negro League veterans Barbee (.284-11-35) and Ernest Burke (15-3).

In the early 1950s, many young African Americans and Latin Americans passed through the league on their way to the major leagues. Vic Power, who returned to Drummondville in 1950 (.334-14-105) was sold to the Yankees for $7,000. Other future major leaguers include Julio Becquer (Drummondville, 1952), Ed Charles (Quebec, 1952), Connie Johnson (St. Hyacinthe, 1951), Humberto Robinson (various teams, 1951-52), and Valmy Thomas (St. Jean, 1951). The quartet of Bob Trice (16-3), Al Pinkston (triple crown winner with a .360-30-121 line), Hector Lopez (.329-8-75), and Joe Taylor (.308-25-112) led St. Hyacinthe to the pennant in 1952.

Farnham became the first team in Organized Baseball to hire an African American manager, Sam Bankhead, in 1951. The team, composed mostly of former Negro Leaguers, including Josh Gibson Jr., was competitive in the first half, but a lack of depth and resources sank it later. Other former Negro Leaguers who sojourned in the Provincial League in that era include Bill Cash (Granby, 1951), Alphonso Gerard (Trois-Rivières, Granby, 1951-52), Everett Marceli (Farnham, 1950-51), Roy Partlow (Granby, 1950-51), Joe Scott (Farnham, St. Hyacinthe, 1950-51), and Archie Ware (Farnham, 1951).

Major changes quickly swept through the league. Quebec and Trois-Rivières moved from the Canadian-American League to the Provincial League in 1951. The same night that Sherbrooke won the 1951 championship, its ballpark burned to the ground, and the team was forced to skip the 1952 season.21 The smallest town in the league, Farnham, could no longer compete and quit, shrinking the league to six teams for 1952. Quebec, which had been a successful affiliate of the Boston Braves, brought a new mentality, and soon all teams were affiliated. The focus quickly changed: Productive but older players, like locals Gladu, Bréard, and Paul Martin, as well as former Negro Leaguers like Ray Brown, Quincy Barbee, and Ernest Burke, were pushed to local independent leagues.

When Sherbrooke rejoined in 1953, it was affiliated with the Cleveland Indians, and fielded an all-White team with an average age of 21.7 years. Even though Sherbrooke won the pennant, it attracted barely half of its 1951 attendance total. Sherbrooke’s time as the dominant team was over, as the Quebec Braves, managed by seven-time major-league All-Star George McQuinn until 1954, were the playoff champion every year from 1952 to 1955.

After the excitement of hosting major-league-caliber players for so many years, the transition to a farm league understandably was not a crowd-pleaser. Some young local players, like future major leaguer Georges Maranda, were popular, but they were few and far between. There was financial fatigue, especially after years of deficits, and while Thetford Mines was added to the league in 1953, Granby and St. Hyacinthe gave up after the season. Drummondville followed after the 1954 season, replaced in 1955 by Burlington, Vermont. As had been the case for the Eastern Canada League 25 years earlier, expanding into Vermont was not a good omen. After losing its affiliation, Sherbrooke quit after the 1955 season. When Trois-Rivières and St. Jean still had not committed to a return in April 1956, the league disbanded.

In these final three years, the Provincial League was a much more typical farm league, the most interesting future major leaguers in that final era in Organized Baseball being Gary Bell and Bobby Locke (Sherbrooke, 1954), Dick Brown (Sherbrooke, 1955), Lou Johnson (St. Jean, 1955), Don Nottebart (Quebec, 1954), and Dan Osinski (Sherbrooke, 1953).

Baseball returned to its local roots in the following years, but by the mid-1960s a strong Provincial League reemerged, in pretty much the same cities.22 Foreign players were initially limited, but that limit was soon lifted and replaced by a salary cap. When that cap was routinely ignored, it too was scrapped, and from 1968 to 1970 the only restriction imposed was that no player could be signed who had played at Double A or above in the past two years. The league attracted players recently cut from the minor leagues, like George Gmelch cited in the introduction; many young Latin Americans looking for a second chance, like Pepe Frias and Fernando Gonzalez, who would make it to the big leagues; and a few former major leaguers, like Felix Mantilla.

Once again, the intense competition between the teams led to ballooning deficits, and only five teams completed the 1970 season. With the Expos debuting in 1969, the baseball landscape was changing in the province. Quebec and Trois-Rivières jumped to the Double-A Eastern League for 1971, becoming affiliates of the Expos and Reds respectively, and killing the Provincial League in the process. Sherbrooke and Thetford Mines would follow in subsequent seasons. The Eastern League adventure lasted until 1977, the last time affiliated minor-league baseball was played in Quebec.

Overall, the Provincial League, through most of its incarnations, refused to accept being a typical Class-C league, as it should have been given the population of its members. The result was a constant cycle between relevance and irrelevance. The high points have been less frequent since, with various senior leagues coming and going, and none approaching the heights of the Provincial League. A few more recent events have evoked memories of the glory days. Independent pro baseball did return to Quebec City (1999) and Trois-Rivières (2012), in the twin stadiums built in 1938, witnesses of much of the Provincial League history. In 2002 the World Junior Championships were held in Sherbrooke, with Yulieski Gurriel and his Cuban teammates winning gold, on the same spot where Silvio Garcia and Claro Duany had celebrated the 1951 Provincial League championship.23

CHRISTIAN TRUDEAU is a professor of economics at the University of Windsor. For the last 20 years, he has researched Quebec baseball history. His findings are documented at LesFantomesduStade.ca.

Acknowledgments

Heidi Jacobs and Patrick Carpentier provided useful comments on early drafts. My work on the Provincial League builds on that of Bill Young and Merritt Clifton.

Sources

In addition to Baseball-Reference and The Sporting News Player Contract Cards database, many Quebec newspapers were consulted (available on the website of the Bibliothèque et Archives Nationales du Québec). Gary Fink’s database of Negro Leaguers in the minor leagues in the first decade of integration was also useful. Other sources include:

Clifton, Merritt. Disorganized Baseball: The Provincial League, from LaRoque to Les Expos, mimeo, 1982.

Paradis, Jean-Marc. 100 Ans de Baseball à Trois-Rivières, 1989.

Notes

1 George Gmelch, Playing with Tigers (Lincoln: University of Nebraska Press, 2016), 235-36.

2 See Patrick Carpentier, “Joe Page,” SABR BioProject, https://sabr.org/bioproj/person/joe-page-2/.

3 The fourth team in 1923 was in Valleyfield, close to Montréal, where it played many local games. It moved in midseason to Cap-de-la-Madeleine, next to Trois-Rivières, after being bought by the local paper mill.

4 Christian Trudeau, “24 Years Before Jackie Robinson, Charlie Culver Broke Barriers in Montréal,” Baseball Research Journal, Spring 2020.

5 The Montréal teams claimed that umpires were intimidated while working in Trois-Rivières in 1922, and briefly refused to return there in 1923 when something was thrown at their manager. Trois-Rivières similarly claimed in 1923 that Montréal won the second-half pennant after umpires were intimidated in a game in Quebec City. The 1922 incident also caught the attention of legendary columnist Ring Lardner. See “Kill the Umpire,” a Bell syndicate column appearing in Ron Rapoport, ed., The Lost Journalism of Ring Lardner (Lincoln: University of Nebraska Press, 2017).

6 Early leagues that used the same name existed as early as 1898, and reemerged periodically.

7 The Montréal Royals returned to the International League in 1928, and their relationship with the Provincial League was not always smooth. While a few exhibition games were organized and a few players were signed out of the league, the Royals also opposed the entry of the league into Organized Baseball and vetoed the addition of a team on the Montréal island.

8 Gray also came back to Trois-Rivières in 1942, this time in the Class-C Canadian-American League.

9 Of course, the playoffs coincided with the start of World War II, which might also have been a factor.

10“Dans le Monde Sportif par Oscar Major,” Le Samedi, October 28, 1939: 8.

11 Powley played in the Provincial League as Allen McEI-reath, the name of a contemporary player who had nothing do to with the Provincial League and split his 1939 season between the Southern Association and the South Atlantic League. Powley later claimed that his huge salary was paid in part by P.J.A. Cardin, the federal public works minister from Sorel. See “Between Ourselves,” Bridgeport Post, August 29, 1948: 35.

12 “Jean Barrette Abandonne la Ligue Provinciale,” Le Droit, October 22, 1940: 10.

13 The league also had teams in Lachine and Acton Vale, but both folded midway through the season, as the caliber of the league quickly improved.

14 “Sherbrooke Aura un Fort Receveur en AI Thomas,” La Tribune, April 21, 1949: 18.

15 “Lanier to Get $10,000 This Year at Drummondville, City of 30,000,” The Sporting News, June 1, 1949: 32.

16 “Molini Dit Que les Clubs de Son Circuit Peuvent Battre Ceux de l’Internationale,” La Tribune, June 4, 1949: 21.

17 Maglie claims he was not in good enough pitching shape in 1949 to stick with the Giants, and he preferred to return in 1950. He is the only jumper who made a lasting major-league impact after 1949. See “Maglie Relates His Story,” The Sporting News, May 2, 1951: 34.

18 Among the players hired by Sherbrooke to replace the jumpers was Blackie Schwamb, less than a year removed from pitching with the St. Louis Browns. He asked for a few days of leave in August and never returned. A few months later he was arrested and later found guilty of a murder in California. See Eric Stone, Wrong Side of the Wall: The Life of Blackie Schwamb, the Greatest Prison Baseball Player of All Time (Guilford, Connecticut: The Lyons Press, 2005).

19 “Canadian Chief Raps Gambling,” The Sporting News, September 28, 1949: 30.

20 “Les Athlétiques de Sherbrooke Ont de Bonnes Chances de Faire de Nouveau Partie de la Provinciale,” Le Courrier de St-Hyacinthe, December 30, 1949: 4.

21 Bill Young, “The Day Sherbrooke Baseball Died,” Sherbrooke Record, September 19, 2006: 7.

22 In 1969, for instance, Sherbrooke, Drummondville, Granby, Trois-Rivières, Québec, and Thetford Mines, all veterans of the 1950s Class-C league, were joined by Plessisville and Lachine.

23 On a personal note, as a volunteer for the event, I was asked to dig into the history of baseball in Sherbrooke to prepare radio spots, which is how I developed an interest in Quebec baseball histaory.