Racing the Dawn: The 29-Inning Minor League Marathon

This article was written by Sam Zygner

This article was published in Fall 2012 Baseball Research Journal

Baseball is one of the few sports not dictated by a time clock, but its beautiful symmetry is what makes it unique: the ultimate game of equal opportunity. Countless contests in history have extended into extra innings. In some cases, overtime matchups have turned into drawn-out affairs leaving only the most ardent fans waiting for the conclusion. This is the story of one of those contests and the players who fought it out.

Arguably, the most famous and well-documented extra-inning game occurred on April 18, 1981, at McCoy Stadium in Rhode Island between the Triple-A International League’s Rochester Red Wings and Pawtucket Red Sox. The contest was halted after 32 innings with the score tied at 2–2 in the wee hours, when the umpiring crew ruled it would be continued at a later date. The conclusion would come more than two months later, on June 23, 1981, when Pawtucket’s Dave Koza singled off of Cliff Speck in the 33rd inning, scoring teammate Marty Barrett and giving the PawSox the victory, 3–2. The one-inning finale took only 18 minutes, but the total game time registered at eight hours, 25 minutes, setting a record.1 However, the longest uninterrupted professional game (in innings) took place 15 years earlier on a balmy June evening at Al Lang Field in St. Petersburg, Florida. What started as a typical game in the Class A Florida State League, would end up breaking a record of its own.2

On that fateful night, June 14, 1966, the struggling Miami Marlins (25–31) found themselves residing in seventh place out of ten teams in the FSL. The Marlins had already dropped the opening game of the two-game series to the second-place St. Petersburg Cardinals (39–17), by a score of 4–2.3 The hometown Cardinals featured the FSL’s best offense and pitching staff. By year’s end they would lead the league in runs scored (567), and ERA (2.24). The Marlins’ offensive attack (506 runs and 28 home runs that season) mirrored the career of their steely-eyed, but light-hitting manager, Billy DeMars. A middle infielder whose major league career consisted of three seasons—one with the Philadelphia Athletics in 1948 and two with the St. Louis Browns in 1950 and 1951—he was known as “The Kid,” and finished his stay in the big leagues with nary a homer and only 14 RBIs in 211 at-bats.4

DeMars’s professional career began in 1943 when, at the age of 17, he signed with the Brooklyn Dodgers to play in the Pennsylvania-Ontario-New York League at Olean, New York.5 He rose slowly through the Dodgers farm system, climbing as high as Class B with Asheville of the Tri-State League before being rescued by the Athletics, who took him in the Rule 5 major league draft and placed him on their 1948 roster.6 DeMars retired as a player following the 1958 season and began his managerial career with Class C Stockton of the California League in 1959. He made several stops in the lower minors before landing with Miami in 1966.7

On the other side of the diamond was future Hall-of-Famer George Anderson. Even then “Sparky,” as he was more popularly known, was already sporting his customary white locks and endearing smile. Like his contemporary across the field, the 32-year-old Anderson was a light-hitting infielder who enjoyed a brief big-league stay, playing one season for the Philadelphia Phillies as their everyday second-sacker in 1959. Anderson’s professional career began in 1953 after also signing with the Brooklyn Dodgers. He was assigned to Santa Barbara of the Class C California League and quickly worked his way up through the Dodgers system. By 1956 he was starring in the IL with the Montreal Royals, and in 1958 he came back for a second season. In 1960–63 he joined the Toronto Maple Leafs, before hanging up his cleats and accepting his first position as field manager for the same Leafs in 1964. By 1966 Anderson was managing in the Cardinals organization in St. Petersburg and was only four years away from his biggest break, being named skipper of the Cincinnati Reds.8

“Sparky” was looking to add another victory to the Cardinals winning streak and was confident that his staff ace, 21-year-old right-hander Dave Bakenhaster, would bring home his club’s sixth straight. Bakenhaster was in his fourth season of pro ball. Although only 21, he had already enjoyed a cup of coffee with the St. Louis Cardinals in 1964, appearing in a couple of games (three innings) before returning to the minor leagues.

Squaring off against Bakenhaster would be a 24-year-old right-hander from Staten Island, Ben Bardes. Enjoying his second stint in the minors, “Big Ben” had just finished serving a two-year hitch in the military. Bardes would be used mostly in relief during the 1966 season, but on this evening his skipper was looking for the New Yorker to give him as many quality innings as possible.9

It was a typical, muggy night in St. Petersburg, and 740 fans passed through the turnstiles. Everything started out uneventfully enough, as both righties exchanged goose eggs through the first six innings. In the bottom of the seventh, the Cardinals drew first blood. With no outs, Cardinals first baseman Terry Milani popped a single into right field and advanced to second base on shortstop Steve Myshrall’s throwing error. Sonny Ruberto followed with a bunt in front of home plate. Marlins catcher Charlie Sands fielded the ball cleanly, but threw wildly past first baseman Dick Hickerson, allowing Milani to score and Ruberto to move all the way to third base. Shortstop Frank Rodriguez then singled, plating Ruberto, and the Cardinals flew ahead, 2–0.10,11

DeMars, sensing that Bardes had gone long enough, signaled to the bullpen, calling for left-hander Hank King to face the next batter: Bakenhaster. King promptly retired the opposing pitcher as well as the next two batters, without allowing a run. King’s appearance was the shortest stint of the night by any hurler: one inning.12,13

Meanwhile, Bakenhaster had been nearly flawless all evening until the eighth, when Sands cracked a ringing single. With Sands hugging first base, DeMars made a fortuitous move. Working with a limited-size roster, Miami’s crafty manager was forced to use one of his pitchers as pinch-hitter. Looking down the bench, he called on one of his mainstays, Lloyd Fourroux, to pinch-hit for King. Bakenhaster worked carefully to Fourroux, running the count to 1–2. It looked as if the Cardinals ace would escape another inning unscathed, but on the next pitch, Fourroux caught hold of a juicy offering and sent the ball flying over the left-field screen, knotting the score at two apiece.14 The husky, 6-foot-2, 215-pound native of Louisiana, having successfully completed his mission, headed to the clubhouse for a shower before making beeline to the concession stand for some hot dogs to watch the remainder of the game. “That was about nine-thirty,” said Fourroux later. “I ran up to the concession stand, got what I wanted, then went and sat in the grandstand for five hours. The game didn’t finish until two-thirty in the morning and I ate four dollars worth of concessions before it was over.”15

Neither team put up a credible threat to break the tie until the 11th inning. With Miami batting in top of the inning, St. Petersburg’s third pitcher of the night, Tim Thompson, allowed three consecutive singles to Fred Rico, Carl Cmejrek, and Frank Reed, handing the Marlins a 3–2 lead. In one of the night’s most unusual plays, Rico, who had just scored the go-ahead run, was followed closely by Cmejrek trying to score from second base. Thanks to a heads-up play by Milani, Cmejrek was caught between third base and home.16

Dennis Denning recounted the odd play:

One of our guys got caught in a rundown. I think you…said it was Cmejrek, but their guy worked it perfectly. And [Milani] was running him down at third base. And so, as he was running he sorta’, you know, was faking with his hand, which you really shouldn’t do; you know. Just keep it there and when you throw it, you throw it, but don’t be faking everybody out including the guy receiving the ball. But anyway, [Milani] lets the ball fly out of his hand accidentally, and he was maybe only fifteen feet from the runner so he had him dead between home and third… He should’ve walked home, you know, missing the ball. So it hits him in the leg, and it bounced straight to their catcher, and it was a bang-bang play at home and he was out. That was an unbelievable play.17

St. Petersburg answered in the bottom of the 11th, matching the Marlins’ feat of three straight base knocks as Jose Villar, Tim Morgan, and Milani all singled off of Miami reliever Richard Thoms. With no outs and the bases loaded, catcher Gary Stone approached the plate with a good chance of driving in the winning run. Instead, he promptly sent a comebacker to Thoms who threw home to Sands for the force out. Sands, trying to take advantage of a double-play opportunity, snapped a quick throw to Hickerson at first base, but threw wildly and Morgan crossed the plate with the tying run. Thoms then settled down and retired the next two batters to close out the inning, but the damage was done. The score stood at 3–3.18,19

For the next 17 innings the two teams traded zeroes. The Cardinals did mount two threats, the first one coming in the 21st inning when they loaded the bases on a free pass to center fielder Archie Wade, followed by singles from Ruberto (who had replaced Rodriguez at shortstop in eighth inning), then Stone. With one out and Paul Gilliford now on the mound, the future Baltimore Orioles hurler coaxed a double-play ball out of Robert Taylor to dodge a bullet. In the 23rd inning with two outs and the Cardinals’ fifth pitcher of the night, Charles Bowlby, on third base and Wade on second base, once again Taylor failed to deliver, grounding out to Gilliford, killing the Cardinals’ chance to win the game.20

Miami’s lone threat, after the 11th inning, came in the 22nd frame when third baseman Denning crushed a Bowlby offering to deep left field that looked like a sure home run. DeMars said after the game, “I knew it was in for a home run. Then this kid out there [Bob Taylor] leaps in the air, sticks his glove over the fence, and grabs the ball.” Taylor, making up for his failure to hit in the clutch, had robbed Denning’s late inning heroics.21

As the ballgame progressed, the attrition of fans in the stands was becoming noticeable. But at game’s end, between 150 and 200 diehard rooters were present.22 Ruberto commented, “A lot of fans left, and when the bars closed at one, they saw the lights on and came back.”23 The few that endured, or later returned, witnessed history. Even neighbors in a nearby apartment building took notice of the proceedings.

Right fielder Gary Carnegie remembers a particularly annoyed gentleman who was trying to catch a few winks:

And then there was a guy when I was in right field, late in the game… I guess he worked midnight or something. And he came home from work and he was screaming from the balcony of an apartment building, “You guys still playing? What the hell is going on?” I hollered up to him, “Yeah we’re still playing.” He watched the game for a while and then he said, “I’m going to bed.”24

As the game went deeper and deeper into extra innings, the players became more aware of the historic significance that was building around them. Ruberto fondly recounts, “I don’t remember who took the photo, but I think it was the twenty-sixth inning, one of the Marlins ran out there. Someone ran out there and took a picture of the scoreboard.” He added, “Then word started spreading that this was the longest game in the history of professional ball and we said, ‘Really?’”25

At 2:00am, Anderson, DeMars, and umpires Lou Benitez and George Molinari huddled around home plate and collectively decided to halt the game, if necessary, at 30 innings. As luck would have it, it would only take one more inning for the end to come.26 An interesting sidelight to this historic game was that according to league rules, the game should have been halted at 12:50am. Umpire Benitez stated later, “I wasn’t aware of a curfew rule, so I let them play.” Later, FSL president George MacDonald determined that the game was in violation of league rules, but that the results would stand.27

The contest had dragged out to the top of the 29th inning. As if the game hadn’t gotten strange enough, things got even weirder when Marlins pitcher Michael Hebert led off the inning with a ringing double off Bowlby. Denning then worked a base on balls, bringing Carnegie to the plate. Carnegie, who had replaced Frank Tepedino earlier in the game, bunted the ball towards the first baseman, Milani. His tap was perfectly placed and Milani was unable to make a play. The bizarreness continued when Rico followed with a ground ball to the right side of the infield. The ball struck Carnegie between first and second, causing him to be ruled out. Hebert, who had crossed the plate with the apparent go-ahead run, returned to third base and Denning remained on second, with the score still tied. The next batter, Cmejrek, strolled to the plate with only one mission, to put wood on the ball, and that he did, driving a fly ball to deep center field and into the waiting glove of Wade. Hebert immediately tagged from third to score, but Denning, in his zeal to pick up an extra run, also made the attempt. He was gunned down on the relay throw from Wade to Coulter to Stone. Going into the bottom of the inning, the scoreboard showed Miami up by one run.28,29

Having just scored the decisive run, Hebert confidently dispatched the Cardinals in the bottom of the inning, retiring Taylor and Coulter on fly balls, and then putting on the finishing touch by striking out Villar to end the game. After almost seven hours, the ecstatic but bone-tired Marlins congratulated each other and headed to the locker room for a well-deserved shower. Final score: Miami 4, St. Petersburg 3.

In a marathon game, there are always some performances that stand out. Arguably, the outstanding feat of the night belonged to Marlins backstop Sands for catching the entire 29 innings. Despite being nearly knocked-out midway through the game by a foul tip and fighting off dehydration, the sturdy Miami receiver played to the end without substitution. “It was hot as hell,” said DeMars. “My catcher [Sands] lost ten pounds, you know.”30 Remarkably, Sands returned to action the next night, catching the second game of a doubleheader against Orlando.

Several players from both squads put in a yeoman’s night of work. Going beyond the call of duty was Miami’s fifth pitcher of the night, Paul Gilliford. He was brilliant in relief, hurling 11 frames (innings 15 through 25), without giving up a run, while striking out seven, walking two, and scattering seven hits. Astonishingly, he had started the previous day’s game going seven innings,31 giving him a total of 18 innings pitched over the course of two days. DeMars, who was short on pitchers, reluctantly chose Gilliford despite his lack of rest.

DeMars laughed heartily as he spoke about his ace lefty’s performance:

Paul Gilliford was a left-handed pitcher on my team… In fact, I forget how many wins [16], he had a great record with a 1.27 ERA… but he pitched the night before and he kept bugging me on the bus about pitching ten minutes of batting practice. And usually I would let them pitch the second day; then a day off, and then they would start the fourth. Well, again I get in this game and it’s like the twelfth or thirteenth inning, you know, how many pitchers do I have? I don’t have many pitchers left so I finally let him pitch ten minutes batting practice. Then we get into the game, it’s in like the twelfth or thirteenth inning, and I said, “Paul go down into the bullpen and see how you feel.” So he goes down there and comes back and he says, “I feel great.” So I put him in the game and he pitches eleven shutout innings!32

The game proved to be a pitchers’ duel, but the evening’s best hitter award belonged to Cmejrek, who collected five hits in 12 at-bats to go along with his sacrifice fly that brought home the winning run. The most crucial smash of the night was Fourroux’s fence-clearer that tied the game. It was one of three homers the broad-shouldered pitcher would hit during the season in 104 at-bats, good enough for third highest on the team behind Carnegie and Rico.33,34

The Cardinals had their own heroes as well, including 19-year-old left-hander Jim Williamson, who chucked eight innings of relief (innings 14 through 21), striking out eight and allowing only one base on balls. Both Villar and Milani banged out four hits in 12 at-bats, and despite taking the loss, Charles Bowlby represented himself well in a relief role, allowing a paltry six hits in eight innings.35

Thus the previous record for longest professional game in innings, a 27-inning affair on May 8, 1965, between Eastern League foes the Springfield Giants and Elmira Pioneers, was broken. The Pioneers had beaten the Giants, 2–1 in a game that lasted six hours and 24 minutes.36 In one of those strange coincidences that are eerily common in the annals of baseball history, there were two future Miami Marlins on the Pioneers roster that night, player/coach Hickerson and Fourroux. Hickerson had appeared as a pinch-hitter, going 0-for-1, and Fourroux had watched from the bench.

A few more numbers of note. Together Miami and St. Petersburg registered 203 official at-bats, 101 and 102, respectively. The two squads combined for 44 hits, of which only six went for extra bases, and 42 runners were left stranded. On the pitching side of the coin, 11 different hurlers appeared in the game, and as a group registered 41 strikeouts, while stingily walking only 12 batters and recording nary a single wild pitch (Sands did have one passed ball).37

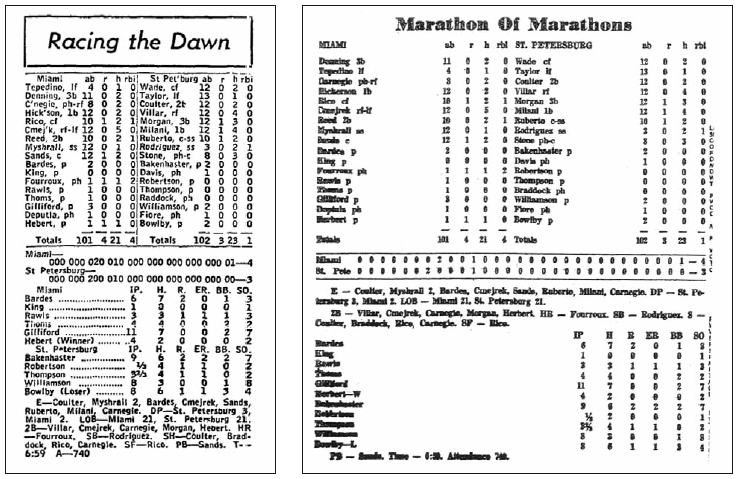

Some discrepancies stand between the two published boxscores.“Racing the Dawn” from The Sporting News, June 25, 1966, page 49. “Marathon of Marathons” from The St. Petersburg Independent, June 18, 1966, page 16-A.

Some discrepancies stand between the two published boxscores.“Racing the Dawn” from The Sporting News, June 25, 1966, page 49. “Marathon of Marathons” from The St. Petersburg Independent, June 18, 1966, page 16-A.

In the aftermath of the now-record longest game there was little rest for the weary. After some hasty freshening up, DeMars and his charges boarded their bus for a quick return trip to Miami to make a scheduled doubleheader at Miami Stadium that same day. It was so early in the morning that the players couldn’t enjoy a late night snack. “One of things I remember, when we did get done with the game there wasn’t even anywhere to eat,” said Denning. “Then we had to drive home to Miami…Cripes, we slept for a couple hours and then we go back to the ballpark.”38 Showing visible signs of exhaustion, the Marlins were dispatched in both ends of a twin bill by the Orlando Twins by identical 3–1 scores.39 The Cardinals fared little better, dropping their next match with the Fort Lauderdale Yankees, 6–2.40 “We lost a doubleheader, but I told my kids, ‘Hey, just do the best you can,’” recalled DeMars.41

Bardes, who spent the last 23 innings observing the game from the sideline, reminisced about the team’s trip back home:

The game finished at two-thirty, and then we had to wash up at the ballpark and then go back over to Tampa for our equipment and clothing because that was the last day of a road trip. And we traveled four and half hours back to Miami. And we had a twi-night doubleheader that night. We got in at, I believe, nine-thirty in the morning…. And by the time we all got our stuff in the car, it was eight of us that lived in this one place over in Miami, right on 78th Street right behind the Playboy Club where we had two apartments… So we got everybody packed, we got everyone in there and we got at least a couple of hours of sleep, but we came back that night and had a twi-night doubleheader… We just didn’t have anybody left.42

In the Cardinals locker room, many of the crestfallen players sat bewildered by what had just transpired. Ruberto recalled Anderson addressing the team afterward with some prophetic words. “I remember after the game, well, we were all exhausted. Win, lose, or draw it was a classic game. We’re all getting into the clubhouse and we’re just sitting on our stools and Sparky got up and he says, ‘I just want you guys to remember this. This is the only way most of us will ever make it to the Hall of Fame, and that was tonight.’”43

Hebert, the hero of the game, had little time to bask in his glory. Upon returning to Miami he was given the news by DeMars that he was being demoted to a lower classification league for rookies. He was sent to Aberdeen, South Dakota, of the Northern League. Despite his 3–3 record and 3.19 ERA, the 18-year-old prospect would spend the rest of the season with the Pheasants under the watchful eye of Cal Ripken Sr.44

DeMars remembers passing the bad news on to his winning pitcher:

Mike Hebert, he was a left-handed pitcher, and before the game started I knew I was going to send him out to Aberdeen, South Dakota, after the game was over. So I didn’t really want to use him in the game, but I think we only had eight pitchers, which means two had to start tomorrow night for the doubleheader, so it left me with six. And I had to use him late in the game, and he gets a double to help us win and he’s the winning pitcher, at that time the longest game in the history of baseball. I couldn’t tell him until we got back to Miami because it so ruined my whole night. Really, because there’s nothing worse than telling a kid that he got sent down. So it was pretty bad.45

The majority of players that appeared during the 29-inning game registered relatively short minor league careers, most under five years. Two participants who made their mark were Dennis Denning and Archie Wade.

Denning, who was robbed of his game-winning home run in the 22nd inning, retired as an active ballplayer in 1967, but stayed in the game in another capacity. After a successful career of coaching at the high school level, Denning accepted a head coaching position in 1995 with the University of St. Thomas (Minnesota). He became one of the most successful coaches at the Division III college level. He was ultimately inducted into American Baseball Coaches Association Hall of Fame in 2012.46 Over his career with the Tommies, Denning garnered 522 wins (.769 win percentage), and two national championships (2001 and 2009).47 He said of his 29-inning game experience, “It was probably the most fun game I ever played. I mean 29 innings, and I’m the kind of guy instead of playing one game I’d rather play a doubleheader.”48

Archie Wade also retired as an active player in 1967, but his life took a much different course. Wade decided to return to school and pursue an education. After graduating from West Virginia University with his master’s degree, he was accepted to the University of Alabama. It was a time when the Civil Rights Movement was in the forefront and in pursuit of his goals he experienced untold racial discrimination. The first black man to integrate the stands during a football game, he was asked to leave during halftime. However, using some of the lessons he learned on the diamond, Wade persevered and earned his doctorate, becoming a Professor Emeritus of Physical Education at Alabama and one of its first black faculty members. Now retired after more than 30 years of teaching,49 he still fondly remembers that June 14 night. “There wasn’t but a few of us that played the entire game, but I was one of the ones that played the entire game. And I’ll tell you what, about one or two o’clock in the morning, I was just trying to make it across the foul line.” He added while chuckling, “I was hoping I wouldn’t trip over anything. It was a long night.”50

A handful of ballplayers from both clubs went on to the big leagues, not counting Bakenhaster who, as mentioned, had already spent time with the St. Louis Cardinals and would not get another big league chance. From the Miami Marlins, four men would make the majors: Paul Gilliford (1967 Baltimore Orioles), Fred Rico (1969 Kansas City Royals), Charlie Sands (1967 New York Yankees, 1971–72 Pittsburgh Pirates, 1973–74 California Angels, 1975 Oakland Athletics), and Frank Tepedino (1967, 1969–72 New York Yankees, 1971 Milwaukee Brewers, 1973–75 Atlanta Braves). Of St. Petersburg Cardinals, there were four more: Chip Coulter (1969 St. Louis Cardinals), Harry Parker (1970–71, 1975 St. Louis Cardinals, 1973–75 New York Mets, 1976 Cleveland Indians), Jerry Robertson (1969 Montreal Expos and 1970 Detroit Tigers), and Sonny Ruberto (1969 San Diego Padres and 1972 Cincinnati Reds).51

As to the opposing managers, Sparky Anderson’s prolific career is well documented. His quotation to his players about ending up in the Hall of Fame proved prophetic. He was inducted into the hallowed hall in 2000. Nonetheless, Billy DeMars enjoyed his own lengthy and rewarding career in baseball. In total, the teaching-oriented manager of the 1966 Marlins spent 11 years in the Baltimore Orioles minor league system before leaving the organization in 1969. He later served as a coach for the Philadelphia Phillies (1969–81), the Montreal Expos (1982–84), and the Cincinnati Reds (1985–87)52 solidifying his reputation as one of the premier hitting coaches in baseball. DeMars later served as a roving minor league batting instructor throughout the 1990s.

By season’s end, Miami had pulled themselves up by their bootstraps, improving their overall record to 75–63, good enough for a fourth-place finish. The first half champion Leesburg A’s would ultimately meet second half champion St. Petersburg in a five-game championship series. Although the Cardinals had the FSL’s best record, they fell to the A’s in the finals in five games, 3–2.53

Even though the game only received minor attention nationwide, both the Miami and St. Petersburg newspapers doled out extensive press coverage for the next two days, putting the spotlight on their respective clubs and the key players. The 6-hour-and-59-minute affair was somewhat forgotten until 1981, when Pawtucket and Rochester hooked-up for 33 innings. Although the game will go down as the second longest in professional history, it still holds the claim as being the longest uninterrupted. Given how ballplayers are monitored today, and various league rules and curfew laws, it is doubtful we will ever see a game of its like again. Sparky Anderson summed it up best, saying, “It was the darnedest thing I’ve ever seen.”54

SAM ZYGNER is Chairman of the SABR South Florida Chapter. He received his MBA from Saint Leo University and his writings have appeared in La Prensa de Miami newspaper. A lifelong Pittsburgh Pirates fan, he has shifted some of his focus to Miami baseball history and has a new book due for release telling the history of the original Miami Marlins (1956–60). His email address is sflasabr@hotmail.com.

Some discrepancies stand between the two published box scores in The Sporting News (left) and The St. Petersburg Independent (right).

Acknowledgments

Over the course of researching this article I interviewed several of the participants involved in this historic 29-inning game who shared their remembrances and personal feelings from their own unique perspectives. To most of these men, the marathon affair was the highlight of their baseball careers and I stand amazed of their clear recollections of the events from that historic night. I would especially like to thank the following: Benjamin Bardes, Charles “Larry” Bowlby, Christopher “Gary” Carnegie, Billy DeMars, Dennis Denning, Sonny Ruberto, Archie Wade, and Jim Williamson for their time and their contributions to this article and our national pastime.

Notes

1. Steve Krasner, “Curtain Falls On 33-Inning Drama,” The Sporting News, July 11, 1981, 45.

2. Burt Graeff, “Breakfast Time, 29-Inning Duel Last 7 Hours,” The Sporting News, June 25, 1966, 49.

3. Bill Buchalter, “Braddock, Cards Drop Miami,” St. Petersburg Times, June 14, 1966, C-1.

4. Baseball-Reference.com.

5. Ibid.

6. Ibid.

7. Ibid.

8. Ibid.

9. Burt Graeff, “Longest Game Ever Played…,” St. Petersburg Independent, June 15, 1966, 16-A.

10. “Marlins Beat Deadline, Saints In 29-Innings,” The Miami News, June 15, 1966, 21-A.

11. Graeff, “Longest Game…,” op. cit.

12. “Marlins Beat Deadline…,” op. cit.

13. Crittenden, op. cit.

14. “Pair Of Iron Marlins,” St. Petersburg Times, June 15, 1966, 16-A.

15. Crittenden, op. cit.

16. “Pair Of Iron Marlins,” op. cit.

17. Dennis Denning, telephone interview, March 3, 2012.

18. Graeff, “Longest Game…,” op. cit.

19. “Marlins Beat Deadline…,” op. cit.

20. Graeff, “Longest Game…,” op. cit.

21. St. Thomas University website, “Long baseball games are old hat for Dennis Denning,” Tommiesports.com.

22. Graeff, “Longest Game…,” op. cit.

23. Sonny Ruberto, telephone interview, March 3, 2012.

24. Chris Carnegie, telephone interview, March 2, 2012.

25. Ruberto, op. cit.

26. Lonnie Burt, “Long Night’s Journey Into Day,” St. Petersburg Times, June 16, 1966, C-1.

27. “Longest Game: It Was Slightly Illegal, Y’Know,” St. Petersburg Independent, June 15, 1966, 17-A.

28. Graeff, “Longest Game…,” op. cit.

29. “Marlins Beat Deadline…,” op. cit.

30. Billy DeMars, telephone interview, July 24, 2010.

31. Bill Buchalter, “Braddock, Cards Drop Miami,” St. Petersburg Times, June 14, 1966, C-1.

32. DeMars, op. cit.

33. “Pair Of Iron Marlins,” op. cit.

34. Graeff, “Breakfast Time…,” op. cit.

35. Graeff, “Breakfast Time…,” op. cit.

36. Al Malette, “Elmira, Springfield Set Marathon Mark In 27-Inning Game,” The Sporting News, May 22, 1965, 33.

37. Graeff, “Breakfast Time…,” op. cit.

38. Denning, op. cit.

39. John Crittenden, “Marlins Lose Two,” Miami News, 16 June, 1966, 23-A.

40. “Tired Cardinals Tumble to Fort Lauderdale 6-2,” St. Petersburg Times, 16 June, 1966, 1-C.

41. DeMars, op. cit.

42. Ben Bardes, telephone interview, 4 March, 2012.

43. Ruberto, op. cit.

44. Baseball-Reference.com.

45. DeMars, op. cit.

46. American Baseball Coaches Association Website. “2012 Hall of Fame Class,” abca.org.

47. College Baseball 360. Website. “St. Thomas Coach Dennis Denning Announces Retirement,” collegebaseball360.com.

48. Denning, op. cit.

49. Gunar Cazers, “Life Histories of Three American Physical Educators,” acumen.lib.ua.edu.

50. Archie Wade, telephone interview, April 15, 2012.

51. Baseball-Reference.com.

52. Ibid.

53. Ibid.

54. Graeff, “Breakfast Time…,” op. cit.